A "New" Set of Bach Canons

by Andrew Porter

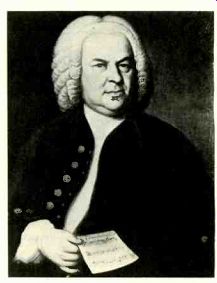

In the well-Known 1746 portrait of Bach by Elias Gottlieb Haussmann, the composer holds Canon No. 13, BMV 1076.

A hitherto unknown work by Bach? Two years ago a stir ran through the musical world, and quite rightly, when Bach's own copy of the printed Goldberg Variations, corrected in his hand, came to public attention. On the last page of the volume, on sixteen neatly ruled staves, the composer had added a set of "Divers Canons on the First Eight Bass-Notes of the Preceding Aria."

The Bibliotheque Nationale bought the precious volume in November 1975. At musicological meetings in France, Germany, and Los Angeles the canons were performed.

Christoph Wolff, who was editing the Goldberg for the Neue Bach-Ausgabe, prepared an edition of them, setting out in full the "solutions" (for the canons are elliptically notated, with a verbal clue for their completion). Two of the fourteen new can ons were already known (see The Bach Reader for details) and "solved"; others were solved in France; some awaited Mr. Wolff's ingenuity.

The first performance of the new canons at a public recital was given by Alan Curtis and Bruce Brown, on two harpsichords, at Berkeley, on May 2, 1976. A few days later they were played in London, by an instrumental ensemble, during the English Bach Festival. The liner note to the Marlboro Recording Society's recording describes a performance at Marlboro last July as "the world premiere of this work in a version for instrumental ensemble." In the Goldberg proper there are already nine canons-at the unison, the second, the third, and so on up to the ninth. One might have thought that, in twenty variations, Bach had already said everything worth saying over the bass of his aria. And yet, from just its first eight notes (G, F sharp, E, D, B, C, D, G), he was able to go on spinning music that is not merely ingenious, but also moving and beautiful.

Until I heard this record, I felt un sure whether the new canons really lent themselves to performance on their own. In Berkeley they were played as a parergon to the complete Goldberg, and certainly formed a moving little epilogue, a microcosm of Bach's contrapuntal art. In the Marlboro performance, gravely, thoughtfully, intently played, with great beauty of tone color and phrasing, they amount to some twelve minutes of music that, I now feel sure, will lend itself to repeated listening.

As prelude, Rudolf Serkin plays the Goldberg aria, on the piano-a concentrated, reflective, crystal clear, and beautifully balanced performance. The recording is close one can hear the pianist's breathing-in a way that puts one into a room with the performers, not down in a hall while they are up on the platform. Then a bassoon plays the eight-note basic theme, very slowly, very firmly, setting down the foundation for all that is to follow. A second bassoon adds the canon simplex of No. 1, and so the canons get under way. None is more than four bars long; in fact No. 13, a close-knit six-part web, is only two bars long. Each of them is played through several times. How many times varies, and is carefully judged-often enough for the ear to discover with delight the way each is made, not too long for it to grow impatient of repetitions.

The arranger of this instrumental version is unnamed; perhaps it was an ensemble effort. It is a convincing one. After two canons from bassoons, the next pair is played by cello and English horn. The change of voice is pleasing, and all the players "utter" with a beauty and purity of timbre comparable to that of a singer who understands the expressive power of a perfectly colored vowel. The scoring keeps the contrapuntal lines distinct. The canons gradually increase in complexity, and begin to span a wide emotional range. Nos. 5 and 9 (played by strings) are buoyant and dashing.

No. 11 is a poignantly chromatic stretch of music, No. 14 a substantial-sounding finale. On the disc, Serkin then plays the Goldberg aria again.

This Marlboro performance persuades me--the written page had left me unsure--that the canons do form a balanced and ordered set, not merely a series of contrapuntal exercises. There were numerological reasons for supposing that this was so.

Bach could have numbered his pieces from 1 to 15, since No. 10 is a pair of related canons. But if A = 1, B = 2, and so on, then the sum of BACH is 14 and of J.S.BACH 41, its "retrograde" (I and J count as one letter); 14 and 41 were his personal numbers. The fourteen canons fall into groups of 4,1,4,1,4. Numerological researches have been pushed to extremes-one scholar attaches importance to the fourteen silver coat buttons he counts on a Bach portrait-but they have come up with some results that cannot simply be dismissed. However, the ear and the Marlboro players pro vide a more pleasingly musical proof of coherence.

A pity, I think, that one of the blank pages of the booklet that ac companies the disc was not used for a facsimile reproduction of the newly discovered Bach page-so much music in little room. It is fascinating to have this under one's eyes and hear the music grow from the composer's few concentrated measures.

Most of the booklet is given to an impassioned plea, by Frederick Dorian. for a higher rating of Reger's music than is common today. And one cannot imagine more persuasive advocates for the Clarinet Sonata, Op. 107, than David Singer and Rudolf Serkin. If any players can win admirers for the piece, it is they.

Their performance is warm-hued, pondered but not ponderous, exquisitely played by both clarinet and piano, filled with poetic and arresting detail, beautifully balanced in ensemble.

Reger was a glutton, for art, work.

music, food and drink. In a 1958 Melos, Willy Strecker, of Schott, re called a day they spent together in London. In the morning, the National Gallery and a silent, careful, methodical inspection of each picture.

Then the National Portrait Gallery and Westminster Abbey, then lunch at a German restaurant with gallons of beer, many feet of sausage, and many dirty stories. Afternoon, the British Museum and the Wallace Collection. That night, after another copious meal, the composer, who had made no comments all day, held forth for hours about all that he had seen and apparently photographed in his memory. Composers' lives and their works aren't necessarily a match, but from Reger's music I of ten get a similar impression of thoroughness, industry, and appetite, not exactly undiscriminating, never careless, but finally exhausting, un appealing because so encyclopedic.

We are told that we need aural experience of the music to love Reger.

Would-be lovers can find plenty of it on disc in the current catalog (but not, rather surprisingly, the orchestral Variations on a Theme of Mozart, his most celebrated composition, and not the Variations on a Theme of Hiller, the work of his I ad mire most). The latest claim of his champions (not, in fact, made by Dr. Dorian, but at the Bonn centenary concerts of 1973, and at some of the London concerts where Reger gets a hearing from time to time) is that Reger is an art nouveau composer, whose restless modulations must be likened to Klimt colors, whose constant embroidery is a form of Jugendstil decoration. I can't hear the resemblance, but listeners might like to try pursuing it.

The more traditional derivation of Reger from Bach is easier to maintain, and I suppose it was the reason for this coupling. The clarinet sonata is a long work-thirty-five minutes, which have been accommodated on one side with no loss of recording quality-and very respectably made.

But it is for the Bach side that I shall be taking this disc down from the shelf.

BACH: Canons on the First Eight Bass Notes of the "Goldberg" Aria.' REGER: Sonata for Clarinet and Piano, in B flat, Op. 107.' Various instrumentalists. David Singer, clarinet; Rudolf Serkin, piano.' [Mischa Schneider, prod.]

MARLBORO RECORDING SOCIETY MRS 12, $7.50 postpaid (Marlboro Recording Society, 5114 Wissioming Rd., Washington, D.C. 20016).

(High Fidelity, May. 1977)

Also see: