[The New Releases]

The Real Kurt Weill:

The London Sinfonietta's DG set of vocal and instrumental works is a landmark in the appreciation of a twentieth-century master.

by Andrew Porter

IN AN INTRODUCTORY NOTE to this album, David Drew says: "Whether you care to mention Weill in the same breath as Hindemith or as Hollander, as Cop land or as Cole Porter, whether you see him as an outstanding German composer who somehow lost his voice when he settled in America or as an out standing Broadway composer who somehow contrived to write a hit-show called The Three-penny Opera during his obscure and probably misspent Berlin youth .... whether you feel him to be important or negligible, whether you love his music or de test it, admire it or despise it-you may rest assured that you are by no means alone." Perhaps Drew draws his limits too closely.

Whether, I would add, like a former professor at Lon don's Royal College of Music, you are prepared to hold up Weill as an example of positively evil music, or whether, like me, you find him one of the four or five great twentieth-century composers whose music means most to you; whose melodies, harmonies, and instrumental sounds get under your skin and into your soul, make you weep for the injuries men do to men and then laugh because goodness and generosity survive; whose sounds inspire you to lofty re solve .... In any event, only the dull of soul and ear can remain indifferent to Kurt Weill. This Deutsche Grammophon album, containing works of his com posed between 1924 and 1929, is a landmark in the re discovery of a composer whose music the Nazis tried to destroy (and literally destroyed, when all the scores and materials they could get hold of were burnt). The earlier, as-it-were composite landmark consisted of the Dreigroschenoper, Mahagonny, Happy End, and Seven Deadly Sins recordings made by Columbia in the '50s with Lotte Lenya as their heroine--Weill-Brecht compositions from 1928 to 1933.

The success of those sets did not altogether destroy two misconceptions about Kurt Weill's music: that it was to be prized, with almost camp appreciation, as a nostalgic evocation of pre-Nazi Berlin; and that Brecht was the dominant partner in the collaboration and dropped Weill when he found in Hanns Eisler an artistically more congenial and musically less emphatic minstrel to set his verses. The first misconception (coupled-in all respect for Lenya's brilliant artistry, it still needs to be said-with the trans positions that Lenya had to make at the time of the recordings) also prompted the use of cabaret and otherwise unsuitable singers in Weill's lyric soprano roles: Covent Garden performed The Seven Deadly Sins with Georgia Brown as the singing Anna; she had to be amplified, and she put everything down a fourth. The City Ballet billed Bette Midler in the role, instead of engaging someone like Judith Blegen.

But in this DG album "all the songs are given to the voices which the composer had in mind, and are per formed in the original keys with the original instrumentation." If a Stravinsky or a Schoenberg album were in question, such a declaration would hardly be necessary. But to anyone who has not previously heard "Surabaya-Johnny" or "The Song of Mandalay" (from Happy End) as Weill originally composed it, the version here should come as a revelation. In Happy End and in the Mahagonny Songspiel the colorful, incisive, piquant, scalp-pricking performance of the London Sinfonietta under David Atherton is what one notices first.

The Sinfonietta was founded nine years ago in the belief that a large musical city needs a regular orchestra whose members are adept at, specialize in, and enjoy playing contemporary music. ( Saint Paul is the only American city I know similarly blessed.) Few major living composers have not worked with or composed for the Sinfonietta, and its "retrospectives" are also famous: of Roberto Gerhard, of Schoenberg (preserved in the five-disc Decca /Lon don album), and now of Weill. At the 1975 Berlin Festival the Sinfonietta was invited to provide Weill memorial concerts (the seventy-fifth anniversary of his birth and twenty-fifth of his death), and the album under review is a direct outcome of those; this spring it is giving a fuller series of Weill concerts in London.

The British singers may not command so immediate an acceptance. But perhaps I am prejudiced.

There is in all of them a kind of soft grain to the timbre, a reluctance to hit the words hard and keep the tone forward, traces of what Anna Russell once wickedly parodied as the nymphs-and-shepherds manner, that is not to my taste in this music (or. for that matter, in any music except a few Victorian pieces composed with King's College mellifluence in mind). Sometimes the soloists assume a slinky and sometimes a tough manner, and either way there seems to be a trace of archness and self-conscious ness about it.

But those are first impressions. It is also apparent that, in addition, they know and love what the music is about. The style is honestly and enthusiastically adopted, even though the essentially English temperaments beneath can't quite be concealed. I wish that Michael Rippon, the bass in Vom Tod im Wald, did not sound quite so much like an Englishman imitating Fischer-Dieskau; that Benjamin Luxon in his vigorous performance of " Mandalay" focused on the real notes more precisely; that Meriel Dickinson and Mary Thomas were not quite so coy of timbre in the "Alabama" song.

Weill, a colleague remarks, needs to be sung as well as Mozart. Part of the trouble, I suppose, is that one might not want to hear these particular voices in Mozart either. Nevertheless, the coupling of the singers' committed, imaginative approach .and the brilliant, eloquent Sinfonietta accompaniments (Atherton has the same sort of rhythmic bite that we hear in Weill's own piano playing) does prove highly impressive and in the end very moving.

The earliest work here is the Violin Concerto (1924), a fascinating piece that has links with the neo classical Hindemith and Stravinsky, and yet stronger links with Mahler's disquieting world as-in the words of T. W. Adorno--it "calls everything secure and playful into question. ... The piece stands isolated and alien: that is, in the right place." Nona Liddell's performance stresses the lyricism, the poetic quality. The orchestral playing is bright, the recording not at all fierce.

Der Protagonist, a one-act opera, appeared in 1925.

The pantomime from it, for wind instruments (a stage band of eight), has a bawdy scenario; musically it is a theme with eight variations and finale well worth hearing in its own right. Winds again plus solo bass (Mr. Rippon) are the forces of Vom Tod im Wald, a very powerful Brecht poem (he later took it into Baal) in a very powerful and beautiful setting.

Vom Tod im Wald also began the Berlin Requiem in Weill's original scheme for it, but was removed be fore the first performance (1929). The Requiem is sung from the score that Drew reconstructed for the BBC revival of 1968, here with three solo voices and the orchestra of winds, drums, guitar, banjo, and harmonium. It was composed for broadcasting-one of the first major commissions of the kind-and its simple strength may reflect the simpler radio technology of the day. I believe it to be a masterpiece.

The Mahagonny Songspiel (1927) is, of course, the germ of the Mahagonny opera, but a very different work-a suite of six vocal numbers and three instrumental interludes, without any connected plot. (It should not be confused with that other "Little Mahagonny," which is a potted version of the opera, rearranged and rescored, not by Weill.) Here the composer starts to form his "song style." The songs of Happy End (1929)--and of The Seven Deadly Sins (1933)--are even more highly developed.

In Happy End, songs and play are not very closely linked; for concert performance, Drew has re-grouped the former in a three-part sequence (Songs of Hell-Fire and Repentance/Songs of Love and Innocence/Songs of the Rival Armies), which forms a very happy presentation of some of Weill's most original, inspired, and affecting music. " Bilbao" is missing, which seems a great pity. ("It resists musically satisfactory incorporation. in a suite-like structure.") But the shattering "Hosanna Rockefeller," absent from the published vocal score, is here; this is the number that caused an uproar at the first performance. ("Enrich the rich with your riches! Hosanna Rockefeller! Hosanna Henry Ford! Hosanna God's own Word! Hosanna, Right and Murder!") The Kleine Dreigroschenmusik, or wind suite from The Three-penny Opera, hardly needs any introduction. In the nursery, I had a disc of Klemperer's early recording of numbers from it (he con ducted the premiere, in 1929), and, accustomed to the timbre of that tubby old Polydor recording, I had to adjust to the brightness of the Sinfonietta version.

Drew's album notes, which provide informative, stimulating, and enlightening comment on all the pieces, are particularly valuable here as they point out the important ways in which the suite is more than a collection of numbers from the show rescored.

This album presents the instrumental Weill, the Weill of the cantatas, and the Weill of the dramatic songs-one musical personality working in three different veins. The last of them is the best known-and I think it can be argued that it was in this vein that Weill made his most original, most distinctive contribution to our musical experience. On that count, the new album is valuable, both in its own right and as a corrective to the musically unworthy versions of the songs-transposed, re-harmonized, accompanied by whatever forces happen to be available-which are so often heard.

On the other two counts it is perhaps more valuable still. I hope that other albums follow: We need the early Recordare, The Lindbergh Flight, and much else. That the City Opera should be playing Street Scene (as once it did) hardly needs saying. That the two symphonies should be in the symphonic repertoire must be plain to anyone who has heard the records of them. But that the Met should be doing Die Biirgschaft is a claim perhaps hard to make until the whole of Weill's achievement becomes as widely known to the public as it deserves to be.

WEILL: Vocal and Instrumental Works. Meriel Dickinson and Mary Thomas, mezzo-sopranos; Philip Langridge and Ian Partridge, tenors; Bemjamin Luxon, baritone; Michael Rippon, bass; Nona Liddell, violin; London Sinfonietta, David Atherton, cond. [Rudolf Werner, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709 064, $23.94 (three discs, manual sequence).

Concerto for Violin and Wind Orchestra, Op. 12. Der Protagonist: Pantomime I.

Vom Tod im Wald, Op. 23. Mahagonny Songspiel. Das Berliner Requiem. Happy End. Kleine Dreigroschenmusik.

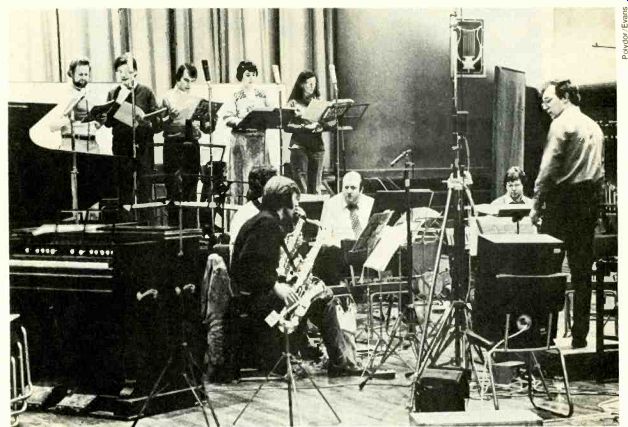

----------- In the recording studio, David Atherton (right)

leads members of the London Sinfonietta and (from left) singers Benjamin

Luxon, Ian Partridge, Philip Langridge, Meriel Dickinson, and Mary

Thomas in songs from Happy End.

(High Fidelity, May. 1977)

Also see:

Link | --Link | --Do We Overestimate Beethoven?