After some fifty years at the top of his profession, the violinist feels out of tune with the times-and doesn't care.

by Estelle Kerner

NATHAN MILSTEIN, who will be seventy-three next New Year's Eve, is the last surviving public per former among that handful of Jewish virtuosos, born in pre-Soviet Russia, who have dominated the violin in this century. Mischa Elman died in 1967 and David Oistrakh in 1974; Efrem Zimbalist, eighty-eight, lives quietly in Reno; Jascha Heifetz, at seventy-six, no longer performs. Of course there are the descendants of Russian Jews, from Yehudi Menuhin and Isaac Stern (who was actually born there) to Pinchas Zukerman and Itzhak Perlman, but none of the old guard survives except Milstein.

"Could this phenomenon be genetic--or ethnic?" I asked him at his New York apartment across from the Metropolitan Museum of Art earlier this year. He did not think so: "If it were a special Jewish gift, Jewish violinists would always have been better in quality. Historically they were not." As for himself, he had not, as a child of five, begged for the violin. It would keep him out of mischief, advised Marya Roisman, a neighbor in Odessa whose son Josef would grow up to become first violinist in the Budapest String Quartet. "My mischief wasn't so terrible," Milstein said, grinning. "I simply was very robust, very physical. The painful part of studying violin was when my mother, my sister wouldn't let me go out and play.

I was forced to practice; otherwise I would be punished. I liked the violin because it was so easy for me. But you can't love music when you're so young. When I started violin I never thought-my mother thought and told me what to do." The boy realized later that his mother had more in mind than prevention of mischief. "Violin playing was a social condition in Russia. Under the tsar, Jews in intellectual towns like Odessa, Kiev towns with a substantial Jewish population couldn't achieve anything in the professions. A Jewish family could buy a violin for two dollars; but even a bad piano at that time cost $300 or $400." Milstein's parents could have afforded a piano his father was a wealthy importer of woolens and tweeds-but the craze for the violin had swept the Pale. Jewish virtuosos did not share the fate of their coreligionists during the era of the 5% academic quota, the Mendel Beilis case, the Black Hundreds, and the pogroms. There was Elman's exemption from military service, by Nicholas II himself, Zimbalist's command performance at Buckingham Palace, Gabrilowitsch's parents' buying two houses in St. Petersburg.

Though Milstein's father professed no interest in formal religion-his sons were not Bar Mitzvah-his mother was Orthodox. "She was practicing the rituals. I loved them. On Friday, it was so beautiful. It was the most cozy thing. The only thing we complained about was that we each always got a little piece of chocolate and only part of an orange-not because we couldn't afford it but because we always had to divide." For more than two years the boy studied with Peter Stoliarsky, an established teacher in Odessa and second violinist in the Odessa Opera Orchestra: "Stoliarsky never taught anything. When you played he said, 'Bad' or 'Good.' " But at eleven, Milstein was invited by the great Leopold Auer to study violin with him at the Imperial Conservatory in St. Petersburg, and when he arrived the following year Auer sent him out on a performance.

========

Some Milstein Milestones

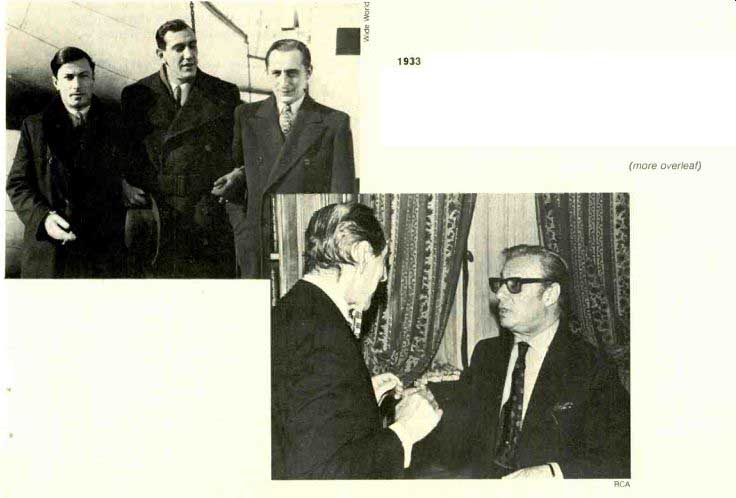

1914: At age ten, three years before the Revolution, as a pupil of Stoliarsky's.

1923: In St. Petersburg with composer Alexander Glazunov, who. as director of the Imperial Conservatory when Milstein was a student there, had come to the rescue of the young violinist and his mother.

1933 With Gregor Piatigorsky and Vladimir Horowitz, returning to New

York on the Mauretania after a European concert tour by the trio. 1976:

Forty-three years later, having just arrived in New York to give the opening

concert at the reconstructed Avery Fisher Hal, Milstein greets his old

friend Volodya Horowitz at the latter's 70-second birthday party.

(more overleaf)

==========

"He said, 'You will not get anything, but it will be very good for you to play.' I got twenty-five rubles, a box of chocolates-and applause. I thought, this is the best profession. You show off, you are applauded, you get paid, and you get chocolate. Now, no chocolate, only applause. You do not get fat from applause.

"But three weeks after I played at the first class, we were afraid to return. We had no permits." Jews needed permits to be in the major Russian cities. Milstein's father, as a first-degree merchant, had a dispensation to remain in St. Petersburg or Moscow-a privilege extended to no one else in the family. Heifetz and Zimbalist had both had trouble with the authorities. Since Heifetz was only thirteen when he came to the Conservatory, his father, who had no permit, did not want to leave him alone in the city. But students admitted to the Conservatory received residency permits (for themselves alone); Auer's solution was simply to admit Reuven Heifetz-aged forty and a good violinist-to his class of child prodigies. When the thirteen-year-old Zimbalist's mother was discovered without a permit, she and her son were driven from their lodging to walk the streets in below-zero temperatures. They arrived at Auer's door shivering, embarrassed, begging for help. It took all of Auer's influence to get Mrs. Zimbalist a one-week permit.

"When I told Auer why I had not come to play," Milstein continued, "he immediately called Alexander Glazunov, director of the Conservatory. He said, 'Look, I have the young Milstein with his mother. They have a problem. Could you help them?' Glazunov was a wonderful person. He said,

'Of course.' We went to Glazunov. He was a gentleman. He stood up and gave my mother a seat.

Then he said, 'The problem will be immediately taken care of.' He called the Minister of Interior and said, 'Sasha, please do something for this young boy and his mother. Arrange that nobody disturbs them.' We went to another office. The superintendent, Vornick, stood up and saluted us Jews! "People exaggerate. Of course things were had.

Officially, sometimes the government encouraged awful things, like pogroms, but they made pogroms where the population accepted them. The Ukrainians and Polish-they were always ready.

But the Great Russians? Never!" Milstein reminisced about his master: "Every young boy who had the dream of playing better than the other boy wanted to go to Auer. He was a very gifted man and a good teacher. I used to go to the Conservatory every Wednesday and Friday at three o'clock for classes. I played every lesson with forty or fifty people sitting and listening. Two pianos were in the classroom, and a pianist accompanied us. When Auer was sick he would ask me to come to his home." It was 1917.

In December, Auer fled to Norway, carrying the legal limit of five hundred rubles, bitterly lamenting the loss of his fortune, his pension, his library, and his priceless gifts. A few months later he was in New York, which with its four or five concerts a day he found the "acme of present-day civilization"; and though he died in Dresden in 1930, he was buried, at his request, in Scarsdale.

Auer's departure from Russia ended Milstein's formal violin studies. "After I was thirteen I never had a teacher. I went to Ysaye in 1926, but he didn't pay any attention to me. I think it may have been better this way. I had to think for myself.

"I was very romantic when the Revolution came. We all shouted! Everybody was in favor of it, even the tsar's brother. I knew things had been bad. When a boy sees women standing in line for bread at six in the morning--as if it were for a Horowitz concert--and waiting until six at night and then they are told, 'Sorry, we don't have any more,' he knows something is wrong. But I had bread." Milstein met Vladimir Horowitz in 1921, in Kiev.

"I went there to play a concert. Horowitz came with his sister, Regina, to hear me. He was hand some and elegant like a greyhound. He came back stage and said, 'My mother and father invite you to tea.' There were music professors at the tea-like Heinrich Neuhaus, years later teacher of Sviatoslav Richter. Volodya (nobody called him Vladimir) played for me later, in Regina's room-his own piano arrangements of operas, Puccini and Wagner. He knew symphonies and operas from memory. After dinner we played sonatas, concertos. I was asked to spend the night-four in the same room: Papa, Volodya, his brother, and me.

The next day I was asked to stay on. I was invited to tea, and I stayed three years." Milstein left Russia on Christmas Eve 1925. "At that time I was sure I would return. When I left, terror was not noticeable yet-it was not organized, not a police state. Horowitz left first. It happened like this: After Horowitz and I played in Moscow, the Commissar of Education, Lunacharsky, very musical, wrote a review about us. He called us 'children of the Soviet Revolution.' Children of the Soviet Revolution? We were children of Imperial conservatories! But Trotsky read the review and said it will be very good to show that Russia is not just materialistic. Trotsky's assistant gave us a letter: 'The Soviet government has nothing against Comrade Horowitz and Comrade Mil stein going out of this country for the purposes of study and cultural progress.' Permission was granted for two years." Milstein was soon famous throughout Europe as both a brilliant soloist and member of a piano trio with Horowitz and Russian cellist Gregor Piatigorsky. He made his American debut in 1929.

Now, after fifty years of eminence, Milstein feels out of tune with the century--and does not care.

Dapper, urbane, impeccable, he is a confessed aristocrat. The red button of the French Legion of Honor is set in the lapel of his elegant English tweed jacket. His violin, which he bought at the close of World War II, was originally called the Goldmann Strad, after the collector who once owned it. "The name sounded like I would be selling onions, so I called it Maria-Therese, after my wife and daughter."

==========

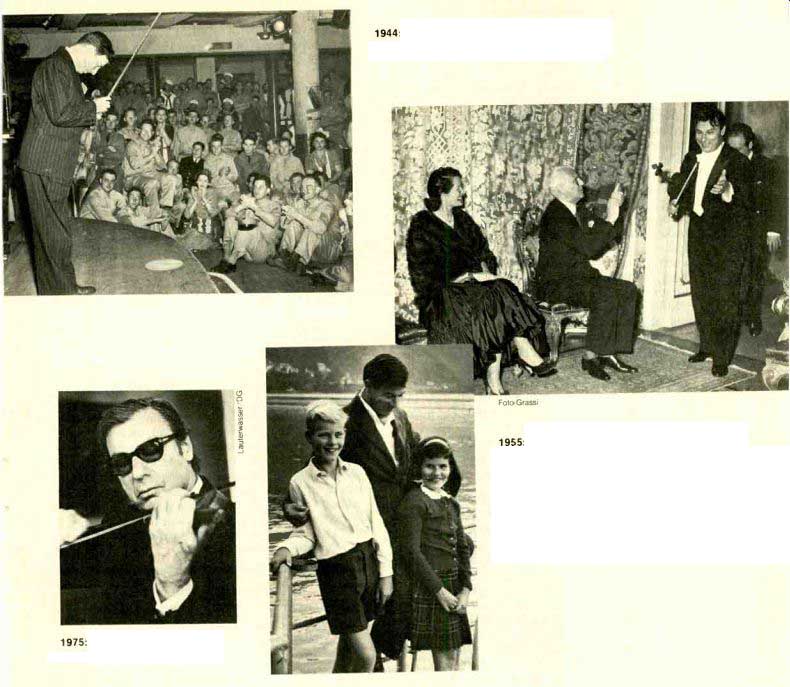

1975: Recording Bach's unaccompanied violin sonatas 1944: Playing for World War II troops at Hollywood's Stage Door Canteen.

1955: After a recital at Siena's Accadema Chigiana, as Count Chigi applauds and Milstein's wife, Therese-whose name forms half the appellation of his Stradivarius-beams. 1957: With the other half of the appellation, his daughter, Maria, smoking Papa's cigarette, on Lake Geneva, Switzerland. The boy is conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler's son Andreas.

===========

As with any true aristocrat, Milstein's manner is all modesty. Yet the volatility of his playing is matched by that of his speech-and of his ideas. A painter himself and a collector of fine art, Milstein says: "You will never again have great master pieces. There is nobody who will spend money for it. Very often, a tyrant, in today's sense, was a cultured personality. That's why you have master pieces. A democratic form of government has to ask a Congress. Good tyrants produce quality. Peter the Great was good. He had St. Petersburg de signed for him. He took experts to Holland and bought a collection of Rembrandt paintings. If he wouldn't do it, nobody would do it. You can't find great jewelry now, for example. Expensive, but not great. Nobody can afford to pay union fees for masterpieces. You would have to have somebody who would tax the masses. We have in our home in London two beautiful French carpets made in the workshop of Louis XV. They were not made to sell someplace. In the time of the Medicis there was a dinner for five hundred titled people. Every body ate on a golden plate bearing his own coat of arms. Then the guests took the plates home. I don't have friends like that," he adds with a laugh. "No body gives me a golden plate.

"I think the more people that are involved in artistic things, the less good they are. Even in food the quality will diminish as more people ask for things. In France the best cuisine is in the small towns. There are more violinists now. Grants create many violinists, but grants disperse your attention and you don't have time to notice some thing extraordinarily good. There is a terrific number of geniuses. But now young people often start to concertize before they have all the equipment.

There is no time for concentration, no time to think.

"I see the difference between now and the past: Music has become more educational than artistic.

Young people must be able to sacrifice for the violin. I don't think it's important to sacrifice for edu cation. You can live happily without education.

But people who are very dedicated to the violin will never be happy unless they play." Milstein doesn't think much of the conducting profession: "People say so-and-so is a great conductor. He cannot be great at twenty-five. Conductor as an artist, a great personality who can teach the orchestra-that is a conductor. But today no body can. Since you only need yourself to be a great violinist, pianist, cellist, singer, you can experiment. You are completely in the music, you make music. Conductors do not make music. They make somebody else play. I made recordings, and when it came through it was because I said some thing, not the conductor. Very often I stop the conductor and tell the orchestra how to do it." Milstein's recordings currently in the catalog, with the exception of the Bach sonatas and partitas for unaccompanied violin (and an imported Brahms Third Sonata with Horowitz), are devoted exclusively to works for violin and orchestra. (See below.) Only the Glazunov and Prokofiev concertos were composed in the twentieth century. Why doesn't he play more contemporary music? "People don't know how to write for the violin anymore. There was never in musical history such a universal lack of quality. The connection be tween Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Wagner is continuous like a chain reaction. There was not even a pause; from Rimsky-Korsakov, the Russian school and French school, and their inter marriage and influence, you had Stravinsky, who started to write in the nineteenth century. Prokofiev wrote his best works when he was nineteen, before World War I. Stravinsky, Bartok, Berg. Finish! That was all written forty-five years ago. Now you have cement music, concrete music, electronic music. Atonal music is a destruction. Every body is looking for something silly. If composers would continue writing traditionally, a gifted per son would come with a good idea. They don't look for the gifted; they look for the intellectual." What does Milstein himself look for in music? "Quality. And virtuosity, which is also quality.

The piano has virtuoso music-Chopin, for example. But the only composers in the nineteenth century who wrote brilliant violin music were superficial musicians: Sarasate, Wieniawski, Vieuxtemps, who tried to make a nice form out of it. The solo playing is not virtuoso--it lacks that quality because it is superficial. Even chamber music should be virtuoso. You play Beethoven's Violin Concerto, you have to play virtuoso. Stravinsky wrote for violin, but he wrote nothing extraordinary. Prokofiev wrote two wonderful concertos and small pieces.

"People go to hear sonatas. But how many sonatas are there? And not all sonatas are possible in a large hall. Beethoven's last sonata, the tenth, if you play it right, in Carnegie Hall or Lincoln Center, nobody will hear it. You can't be intimate there." Milstein is considered one of the most passion ate interpreters of Beethoven and Bach. His Deutsche Grammophon recording of the complete Bach Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin was one of HIGH FIDELITY'S three best records of the year in 1976. "Bach was the greatest, without improvement. Paganini may have invented more exterior things: harmonics, pizzicato, showoff music. But Bach's was all authentic violin sound. If you ask me who made the greatest contributions to music I would say: Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, Haydn, Schubert, Schumann-like everybody would say.

Everyone's gods are the same." At seventy-two, except for a back that begs pampering, he retains a youthful ebullience and vitality. He was to make his first overseas flight-from New York to Switzerland-shortly after I saw him.

"I hope I like it. I will take two scotches before I board the plane." He laughed.

But he does not regret aging. Returning to the subject of the young, he said, "A gifted person can not develop badly. Talent will always put him on the right track. He might not succeed commercially, but he will always be good-in a way, morally good too. The majority of young people now are more brilliant. They know more than we knew fifty years ago. But people exaggerate the importance of young people. People lose perspective.

Whatever they do as young people, if they are gifted, they will do better when they get older.

"The young are important only because eventually they will become old."

----------

Sampling the Art

Milstein's Currently Available Discs

BACH, VIVALDI: Concertos. ANGEL S 36010.

BACH, VIVALDI: Double Concertos. With Morini. ANGEL S36006.

BACH: Sonatas and Partitas. DG 2709 047 (3).

BEETHOVEN: Concerto. Philharmonia, Leinsdorf. ANGEL S 35783.

BRAHMS: Concerto. Philharmonia, Fistoulari. SERAPHIM S 60265.

Vienna Philharmonic, Jochum. DG 2530 592. Tape: 411, 3300 592.

BRAHMS: Sonata No. 3. With Horowitz. RCA ( Germany) 26.41339 (mono; imported by German News Co.).

BRUCH: Concerto No. 1. MENDELSSOHN: Concerto in E minor. Philharmonia, Barzin. ANGEL S 35730.

Dvorak, Glaszunov: Concertos. New Philharmonia, Fruhbeck de Burgos. ANGEL S 36011.

Goldmark: Concerto. BEETHOVEN: Romances. Philharmonia, Blech and Milstein. SERAPHIM S 60238.

MENDELSSOHN: Concerto in E minor. Tchaikovsky: Concerto. Vienna Philharmonic, Abbado. DG 2530 359.

N.Y. Philharmonic, Walter; Chicago, Stock. ODYSSEY Y 34604 (mono).

MOZART: Concertos Nos. 4, 5. Philharmonia. ANGEL S 36007.

PROKOFIEV: Concertos Nos. 1, 2. Philharmonia, Giulini; New Philharmonia, Fruhbeck de Burgos. ANGEL S 36009.

SAINT-SAENS: Concerto No. 3. CHAUSSON: Poeme. Philharmonia. Fistoulari. ANGEL S 36005.

VIVALDI: Concertos. ANGEL S 36001.

MUSIC OF OLD RUSSIA. ANGEL S 36002.

-------------