Reviewed by: ROYAL S. BROWN, SCOTT CANTRELL, ABRAM CHAPMAN, R. D. DARRELL, PETER G. DAVIS ROBERT FIEDEL SHIRLEY FLEMING ALFRED FRANKENSTEIN KENNETH FURIE HARRIS GOLDSMITH DAVID HAMILTON DALE S. HARRIS PHILIP HART PAUL HENRY LANG IRVING LOWENS ROBERT C. MARSH ROBERT P. MORGAN JEREMY NOBLE CONRAD L. OSBORNE, ANDREW PORTER It. C. ROBBINS LANDON, PATRICK J. SMITH, PAUL A. SNOOK, SUSAN THIEMANN SOMMER

Neville Marriner-Boyce rescued with enthusiasm and verve.

--------------

Explanation of symbols

Classical:

Budget

Historical

Reissue

Recorded tape:

Open Reel

8-Track Cartridge

Cassette

--------------

BACH: Concerto Reconstructions. Alice Harnoncourt, violin; Jürg Schaeftlein, oboe d'amore; Vienna Concentus Musicus, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.

TELEFUNKEN 6.42032, $8.98. Tape: 4.42032, $8.98.

Concertos for Violin and Strings: in 0 minor, from S.1052: in G minor, from S. 1056. Concerto for Oboe d'Amore and Strings, in A, from S. 1055.

As every Bach connoisseur must be aware, it's now generally agreed that all the harpsichord concertos are the composer's own re-workings of scores originally starring a violin or woodwind soloist. It was as far back as 19.10. indeed, that Joseph Szigeti and Fritz Stiedry were the first to record a reverse transcription's--the presumed violin original of S. 1052, which the Harnoncourts perform here using period or replica instruments exclusively. Alice Harnoncourt also is featured in a C minor violin reconstruction of the F minor Harpsichord Concerto, S. 1056 (performed with modern instruments by Itzhak Perlman and Daniel Barenboim on Angel S 37076, June 1975; an alternative flute "original" was recorded by William Bennett and Neville Marriner on Argo ZRG 820, December 1976). The third work in (his release is the presumed oboe d'amore original of the A major Harpsichord Concerto, S. 1(155 (recorded by Neil Black and Marriner on Argo ZRG 821. December 1976). Bach specialists who cherish the Harnoncourts' earlier concerto programs will delight in this one. And even non-specialist listeners are likely to be stimulated as well as startled by the crackling high-voltage energy of these performances and by the vibrant, if sometimes rough. sonorities. Yet today's musicological purists have their own idiosyncrasies. and I question both the authenticity and the interpretative effectiveness of the Harnoncourts' tendency. in slow passages. to aspirate. as it were, individual notes in a phrase or coloratura melisma, following each stressed attack with a quick. slight decrescendo on the same note.

This makes for clear-cut articulation. to be sure, but when overindulged it becomes scarcely less annoying, in its picket-fence jaggedness, than anachronistic use of vibrato or "expressive" rubato.

Fortunately this mannerism is a relatively minor flaw in an otherwise bracingly exhilarating program. If the delectable Argo versions of S. 1055 and S. 1056 are safer general recommendations, the present ones have their unique attractions: not least Jürg Schacftlein's big, almost horn-toned oboe d'amore playing in S. 1055 and Alice Harnoncourt's hard-driving bravura in S. 1052, more exciting than any recorded performance since Szigeti's (which was included in Columbia's six-disc "Art of Joseph Szigeli." M6X 31513. January 19:3).

R.D.D.

Boyce: Symphonies (8). Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Neville Marriner, cond.

[Chris Hazell, prod.] ARGO ZRG 874, S8.98. Tape: KZRG 874, $8.98.

Listening today to these now infectiously exuberant, now wistfully lyrical little "symphonies." it's hard to realize that they were allowed to languish in near-oblivion for many years. Unfortunately, Boyce still is better known to eighteenth-century specialists than to the general public. despite the existence of three quite good previous stereo versions of the symphonies.

None of the earlier recordings matches the vibrant presence of Argo's engineering or the irresistible enthusiasm and nippy verve of Neville Marriner and his academicians: the oboe and flute soloists are particularly delectable. It can be objected (as Roger Fiske did in Gramophone) that Marriner takes some of the middle movements too slowly (several are in fact marked vivace), as if to foreshadow later true symphonic slow movements, but I find that he makes a persuasive case for his tempo choices, idiosyncratic though they may be.

If you've never heard these works, some of the finest last flowerings of baroque-era theatrical music (for most of it was written for stage productions many years before the first publication in 1760), sample the festive No. 5. or No. 7 with its spiritoso first-movement fugue and galumphing jigg finale.

K.D.D.

BRAHMS: Ein deutsches Requiem, Op. 45.

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, soprano; Hans Hotter, baritone; Vienna Singverein. Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan, cond. [Walter Legge, prod.] ANGEL ( Japan)

EAC 30103, S9.98 (mono) [from COLUMBIA SL 157, recorded 1947] (distributed by Capitol Imports). In September 1946. when Walter Legge and the EMI recording team came to Vienna for their first postwar recordings in that city.

both Wilhelm Furtwangler and Herbert von Karajan were under Allied interdict, prohibited from conducting in public. Legge persuaded the occupation authorities to let Karajan make recordings with the Vienna Philharmonic, which were to establish the Austrian as the major conductor of the new generation: he was thirty-eight at the time.

The Karajan Vienna series continued until 1950, and the bulk of it has recently been transferred to LP by EMI's dubbing wizard Anthony Griffith, for release by its japanese affiliate. Despite the high price, some of the usual amenities are missing: Although the labels and the fonts of the jackets are in English. just about everything else is in Japanese (for the choral works, the original German is given. along with a Japanese translation). The prize of the lot is this warm, propulsive, richly nuanced performance of the Brahms German Requiem, a far more involved and involving affair than either of Karajan's subsequent recordings-both of them so devoid of significant events that they put me in sympathy with Bernard Shaw's naughty witticism that this Requiem could only be borne patiently by the corpse. The 1947 recording is quite different. and includes as lovely and unaffected a piece of singing as Elisabeth Schwarzkopf ever gave us. before she became the excessively self-conscious virtuoso of the Fifties. Hans Hotter. too, is in rather good form, imposingly Old-Testament in manner. The new transfer, a shade low in level to accommodate the whole piece on a single disc, is full and solid: a few of the 78 sides grind. but not obtrusively.

Especially if you are not--as I am not-anything like an automatic admirer of Karajan's later work, I commend this Brahms to your attention. In fact, the whole series is rather impressive. On a total of twelve discs. it encompasses all of the Karajan/VPO series for English Columbia except the two Mozart operas (Nozze and Zauberflate, still available in European pressings). two Josef Strauss waltzes, the Cavulleria Intermezzo, Liil's final aria sung by Schwarzkopf, and a few vocal recordings that Karajan conducted anonymously, apparently because he was afraid of being typed as an "accompaniment conductor.'' (Among the latter, two are scheduled for release soon by English ENII: the Presentation of the Rose from Rosenkavalier with Schwarzkopf and Seefried, and a previously unreleased Salome finale with Welitsch, one segment of which will be missing, as the matrix was irreparably damaged in transit from Vienna to London.) To sum up briefly the other records in the series: The major works are Beethoven's Ninth (EAC 30101), Fifth and Eighth (E 1C 30102), the Schubert C major (EAC 30104), Tchaikovsky's Sixth (EAC 30105), and Brahms's Second (EAC 30106). Two Mozart discs include Symphonies Nos. 33 and 39 (EAC 30107). the Clarinet Concerto (Leopald Which the soloist). Eine kleine Nachtmusik. the Masonic Funeral Music.

and the Adagio and Fugue (EAC 30108). Richard Strauss's Metamorphosen is coupled with some Wagner choral excerpts (EAC 30109), two discs are devoted to Strauss waltzes and overtures (EAC 30110/ 1). and a catchall "Popular Concert" includes Tchaikovsky's Romeo and Juliet, the overtures from the complete Mozart opera recordings. the Marion Lescaut Intermezzo, and Schwarzkopf singing "O mio habbino caro.' For those interested in the development of Karajan's style-and. indeed, the history of modern conducting in general-all of these are fascinating documents. His admiration for Toscanini is clear enough. but not in any way slavish: like the Brahms Requiem. the Mozart performances have Toscaninian attributes without being in the least like Toscanini's actual performances of this music. Karajan apparently derived from the older conductor an ideal of textural clarity and rhythmic consistency-but applied it in terms of his own temperament and ideas about the music. The Schubert symphony is especially impressive in its coherence, and the Beethoven works make fascinating comparisons with the three subsequent recordings from three subsequent decades. Even then, Karajan's Johann Strauss was more sleek than idiomatic, and the Wagner choral numbers are curiously dull, though the Metamorphosen-the first recording ever of the piece-is fervently played.

-------------

Critic's Choice

The most noteworthy releases reviewed recently BACH: Violin Sonatas and Partitas. Végh. TELEFUNKEN 36.35344 (3), Oct.

BARTOK: Mikrokosmos. Ránki. TELEFUNKEN 36.35369 (3), Oct.

BARTOK, STRAVINSKY: Two-Piano Works. Kontarskys. DG 2530 964, Nov.

Boccherini: String Quintets. Quinteto Boccherini. HNH 4048, Oct.

BRAHMS, SCHUMANN: Piano Works. Kubalek. CITADEL CT 6027, Nov.

BRITTEN: Various Works. Baker, Britten, et al. LONDON OS 26527, Nov.

DVORÁK: Quartets, Opp. 51, 105. Gabrieli Ot. LONDON TREASURY STS 15399, Nov.

FALLA-HALFFTER: Atlántida. Tarrés, Sardinero, Frühbeck. ANGEL SBLX 3852 (2), Oct.

HAYDN: II Mondo della luna. Auger, Alva, Dorati. PHILIPS 6769 003 (4), Dec.

HOLST: Choral Works. Groves. ANGEL S 37455, Oct.

Liszt: Piano Sonata.

SCHUMANN: Fantasy. De Larrocha. LONDON CS 6989, Oct.

MENDELSSOHN: Symphonies (5). Masur. VANGUARD CARDINAL VCS 10133/6 (4), Oct.

MESSIAEN: Turangalila Symphony. Previn. ANGEL SB 3853 (2), Dec.

MOZART: Violin Sonatas. Shumsky, Balsam. MHS 3475/80 (6), Oct.

Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition; Night. Markevitch. MHS 3650, Oct.

POULENC: Organ Concerto; Concert champétre. Preston, Previn. ANGEL S 37441, Nov.

PURCELL: Dido and Aeneas. Troyanos, Stilwell, Leppard. RCA ARL 1-3021, Dec.

SHOSTAKOVICH: Quartets Nos. 1, 3. Gabrieli Qt. LONDON TREASURY STS 15396. Quartets Nos. 4, 12. Fitzwilliam Ot. L’OISEAu-LYRE DSLO 23. Nov.

Stravinsky: Pulcinella Suite, et al. Boulez. COLUMBIA M 35105, Nov.

VIVALDI: Choral Works, Vols. 1-2. Negri. PHILIPS 6700 116 (2), Nov.

IDIL BIRET: Piano Recital. FINNADAR SR 125 (direct-to-disc), Dec.

LEONARD PENNARIO: Daydreams (Piano Recital). ANGEL S 37303, Nov.

NIGEL Rogers: Airs de Cour: French Drinking Songs. PETERS PLE 050, Dec.

RUDOLF SERKIN: On Television (Piano Recital). COLUMBIA M2 34596 (2), Nov.

MARTIAL SINGHER: French Song Recital. 1750 ARCH RECORDS 1 766, Nov.

SPANISH CATHEDRAL MUSIC IN THE GOLDEN AGE. TELEFUNKEN 36.35371 (3), Dec.

----------------

Some of these recordings have circulated here before, mostly on Columbia or Entré: the Brahms Second was an early Angel. In the several cases where I've been able to make comparisons, the Griffith transfers are markedly superior in clarity and range (it turns out that he was also the original engineer on some of these sessions), and the Japanese surfaces are spectacularly clean.

The beginning of Karajan's recorded career goes back still further than these records: During the Nazi years, he made overa hundred 78-rpm sides for Deutsche Grammophon, some with the Concertgebouw and the Italian Radio orchestras. The Mozart Haffner and Strauss's Don Juan were once available on Decca DI. 9513 and DL 9529,. respectively, and the Zigeunerlxiron Overture in BASF's Berlin Staatsoper anthology (98-22177-6). Perhaps DG will consider matching EMI's Karajan historical project with one of its own? D.H.

BRAHMS: Symphony No. 2, in D, Op. 73. Chicago Symphony Orchestra, James Levine, cond. [Thomas Z. Shepard, prod.] RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-2864, $7.98. Tape: ARK 12864, $7.98; . ARS 1-2864, $7.98.

Comparisons:

Toscanini/NBC Sym. in Victr. VIC 6400 Boult/London Phil. Ang. S 37032 Bohm / Vienna Phil. DG 2530 960 Monteux/Vienna Phil. Lon. Treas. STS 15192 Levine's Brahms Second. like the earlier installments in his now-completed cycle. resembles Toscanini's NBC Symphony recording: Textures are crisp and lean: rhythm is tight: tempos avoid extremes (the second movement is an Adagio with the accent on the composer's "non troppo": the third movement is leisurely): there is no first-movement repeat.

While the Toscanini-Levine way brought surging rhetorical power to the Third Symphony and fresh rigor to the First and Fourth, the Second wants more ardor than it gets here. The cellos need to sing more,

-----------

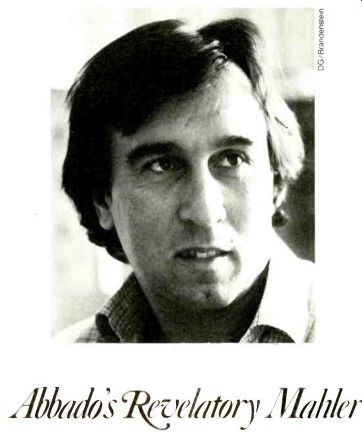

Abbado's Mahler

by Abram Chipman

After some twenty-five years of hearing the Mahler Fourth Symphony in every conceivable interpretive guise I scarcely would have thought it possible, but from the first few bars the music on this recording sounded pristinely fresh and new.

Claudio Abbado lets it all pour forth with the Schubertian simplicity. lyrical warmth, and childlike wonderment of the venerable premiere recording under Bruno Walter (Odyssey 32 16 0026. rechanneled). At the same time flashes of rubato, brilliant color, and dramatic boldness are as striking as in the versions of Willem Mengelberg (Philips. deleted) and James Levine (RCA ARL 1-0895). To top it all off, the impeccability and innocence of Frederica von Stade's singing in the Wunderhorn-inspired finale seem of a perfection heretofore eluded on disc.

More critical rehearing and spot comparisons with my favorite earlier recordings only confirmed the initial verdict. Everything that might surprise a listener in Abbado's reading--sudden wispy ppps in the violins, a prominent bass clarinet or bassoons in some grotesquely parodistic movement, the roof-raising climax of the slow movement, or even the sequence of no fewer than ten tempo changes in the last pages of the first movement--is right there in the score.

Mali-Some more magic tricks: Abbado's timing of 23:25 for the slow movement is likely the longest on records. Yet Mengelberg, who takes some two minutes less. sounds more calculated in his Romanticism. Levine. at about 22 minutes. and George Szell ( Columbia MS 6833), at just under 21, strive for infinite stillness and immobility: Abbado lets the music flow and gambol in a dreamlike ecstasy, and it is over too soon.

Von Stade's churchly, white-toned purity turns out. on closer examination. to he ripe with sensuously expressive and humorous touches (e.g.. the lift and bounce to "Wir lanzen and springen"). Just negotiating the notes and the line overextends most of her competitors, but I never particularly noticed that-or the matronly timbre of some of the others-until Von Stacie came along.

The playing of the Vienna Philharmonic. as captured by DG's technological wizardry, sounds as if it comes straight from the brain of the composer.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 4, in G. Frederica von Stade, mezzo-soprano; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Claudio Abbado, cond.

[Rainer Brock, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 966, $8.98. Tape 3300 966, $8.98.

-----------------

... though Levine's rather détaché phrasing of the first movement's big lyrical tune (reminiscent of Antal Dorati's Mercury recording) is at least interesting. The horns at the opening aren't as lustrous as they are in some Central European renditions. The finale, as such conductors as Furtwangler, Jochum. and Walter have shown, responds to more brio and excitement. Save for a touch of whine in the violins' upper register, the Chicago Symphony responds in smart and finely honed fashion: the sound is closer to the mid-auditorium perspective of Levine's First (ARL 1-1326, May 1976) than to the more visceral Third (ARL 1-2097, January 1978) and Fourth (ARL 1-2624, July 1978). For a brisker, airier Second, I would suggest Sir Adrian Boult's with the London Philharmonic on Angel (with the Alto Rhapsody. sung by Janet Baker); for a more searching, longer-breathed approach, I heartily recommend two Vienna Philharmonic recordings-Karl Bohm's on DG (with the Haydn Variations) and Pierre Monteux's on London Treasury. If. however, a coolly objective approach appeals to you, Levine's is the clear choice among separately available stereo versions. His cycle as a whole, assuming it appears in boxed form, will strongly challenge my previous choices, the richly expansive Sanderling/ Dresden State Orchestra set (Eurodisc 85 782 XHK) and the high-spirited if less virtuosic-but also less expensive--Abravanel/Utah Symphony set (Vanguard Cardinal VCS 10117/20). Final hint: A Levine/Chicago 13rahms disc of the Haydn Variations and the two overtures would be welcome.

A.C. BRUCKNER: Symphony No. 5, in B flat. Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan, cond. [Michel Glotz, Cord Garben, Hans Hirsch, and Magdalene Padberg, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2707 101, $17.96 (two discs, manual sequence). Tape: 3370 025, $17.96.

Bruckner: Symphony No. 5, in B flat. Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Kurt Masur, cond.

VANGUARD VSD 71239/40, $15.96 (two discs, manual sequence). Comparison: Haitink/Concertgebouw Phi. 6700 055

The compelling virtues of Karajan's Fifth (the one Bruckner symphony in his recent DG series that is a first recording rather than a remake) are its rhetorical power. the brilliance and finesse of the orchestral playing. and the range and solidity of the engineering. Masur's recording is less spectacular instrumentally but boasts a darkly bronzen sonority and self-effacing authority characteristic of the conductor's Bruckner series.

Masur is steadier in pulse: unlike Karajan, he resists the temptation to broaden at such points as the brass fanfares near the symphony's opening and the introduction of the chorale theme in the finale (bar 175). Nor does Masur hurry the pizzicato figures in the first-movement coda. More importantly. he evinces greater security in the four-against-six passages of the slow movement. If Karajan is not above toying with tempos for expressive ends, his reading is in general as smartly and dramatically paced as Bernard Haitink's, which in turn is. on the whole, even sturdier in rhythm than Masur's (the notable exception being the latter's monumentally rocklike finale). Masur's more moderate pacing sometimes vitiates indicated contrasts within pavements, as in the first movement and the scherzo.

Masur's orchestra is less virtuosic than Haitink's or Karajan's--though the slight relative thinness of string tone does allow much wind doubling to be heard (e.g., flutes and violins near bar 50 of the slow movement). Between the Concertgebouw and the Berlin Philharmonic, I prefer the former's crisper, more pungent playing to the latter's lusher. smoother sound, but in matters of dynamic contrast--from whispering ppps to shattering fffs--the new DG recording easily surpasses all competitors.

Karajan's Fifth now joins Haitink's and the deleted Klemperer/Angel as my top choices, with Masur's a close and idiomatic runner-up. On the horizon, however, are the first release of a mono live performance by Eduard van Beinum and the Concertgebouw (in a Philips set devoted to the conductor) and Eugen Jochum's Dresden/EMI remake.

A.C. CHOPIN: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2, in F minor, Op. 21*; Nouvelles etudes (3), Op. posth.; Scherzo No. 2, in B flat minor, Op. 31. Emanuel Ax, piano; Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, cond.". [Jay David Saks, prod.]

RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-2868, $7.98. Tape: ARK 1-2868, $7.98; ' ARS 1-2868, $7.98.

CHOPIN: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2, in F minor, Op. 21; Andante spianato and Grande polonaise brillante, Op. 22.

Bruno Rigutto, piano; Luxemburg Radio Orchestra, Louis de Froment, cond. [Ivan Pastor, prod.] PETERS INTERNATIONAL PLE 045, $7.98.

Since Chopin composed his F minor Concerto at the age of twenty-one. perhaps it is best served by pianists full of sprint and grace, which may or may not he synonymous with youth. In any event, both Ax and Rigutto decidedly qualify.

Not that their performances are at all similar. Rigutto, for all his technical brilliance and aristocratic glitter, remains essentially decorative and salon-like. Ax suggests wider, more heroic scope. Though he too shapes Chopin's filigree suavely, the delicacy of his cascading pianism is counterbalanced by slower tempos. thunderous fortes, and breadth of phrase: his treatment is freer, less symmetrical.

The orchestral advantage too is all to RCA. Ormandy's forces in truth sound too massive (especially in the double-bass department), but the Philadelphians' elegant sonority contrasts pointedly with the seedy strings and raw brasses of the Luxemburg Radio Orchestra. The accompaniment may be a secondary consideration in Chopin's concertos, but it is important enough to make the edginess of the Peters edition a distinct annoyance. Both versions give the tutt is uncut.

The fillers are consistent with the concerto performances. Ax offers introspective readings of the three Nouvelles etudes and a coolly incisive account of the Beethovenian II flat minor Scherzo. Rigutto plays the Andante spianato and Grande polonaise brillante with good taste and technical aplomb, and here the orchestral part is so minor that the Luxemburgers do little harm.

RCA's larger-than-life sonics seem to me to misrepresent Ax's full. round sonority.

The inflated ambience confuses the bass line and imparts a tacky percussiveness uncharacteristic of the pianist's tone as 1 have heard it in concert. The Peters sound is of the conventional close-up type. Rigutto's instrument also tends to glassiness but has greater definition in the bass. 11.G. DONIZETTI: La Favorita-See Rossini: L'Italiana in Algeri.

G. GERSHWIN: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, in F'; Rhapsody in Blue'. Pyotr Pechersky" and Alexander Tsvassman', piano; Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, Kiril Kondrashin, cond."; U.S.S.R. Symphony Orchestra, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, cond.'. [Alexander Griva` and David Gaklin', prod.] WESTMINSTER GOLD/MELODIYA WG 8355, $3.98.

Foreign musicians apparently deem George Gershwin's work even more quintessentially " American" than we do, but their often heavily accented. unidiomatic performances usually strike American listeners as awkwardly self-conscious. So I was surprised to discover how much these Russian performances have going for them, although on reflection that affinity may not he wholly coincidental (it is worth remembering that Cershwin's father was horn Morris Cershovifz in what was then St. Petersburg). The appeal of this Rhapsody in Blue is mostly its enthusiasm. Both soloist Alexander Tsvassman and the orchestra are heavy-handed. and the rather thick, over-resonant 1960 recording italicizes the tumultuousness of the reading (and there's a hint of master-tape speed uncertainty in the slight twanginess of sustained piano tones). But there's fine swaggering bravura here and, miraculously, the fat andante moderato tune isn't as sentimentalized or inflated as it often is by American interpreters.

In the more substantial Concerto in r.

Pyotr Pechersky proves a more authoritative vet also more restrained soloist than Tsvassman; he and conductor Kiril Kondrashin give a relatively non-foreign-accented reading. distinguished by its genuine gusto and in the more lyrical passages by surprisingly moving (if scarcely very hluesy) tenderness. The 1967 recording. except for some brittleness in the piano's upper register. is markedly cleaner and more natural-sounding.

Of course. there's no real competition here for fully satisfactory American recordings. but there aren't so many of these as might reasonably he expected. (I still stick with the 196(1 Wild/Fiedler versions for RCA.) At its budget price. the present pairing is fascinating both in its own right and for its illumination of the Russian kinship of this by no means wholly "American" music. R.D.D. KRENEK: From Three Make Seven, Op. 171*; Horizon Circled, Op. 1960; Von vorn herein, Op. 219'. Southwest German Radio Orchestra" and ensemble'. Ernst Krenek, cond. [Giveon Cornfield, prod.) ORioN 78290. $7.98.

KRENEK: Four Pieces for Oboe and Piano, Op. 193.

WUORINEN: Composition for Oboe and Piano.' Moss: Unseen Leaves' James Ostryniec, oboe; Ernst Krenek" and Charles Wuorinen', piano; Ruth Drucker, soprano'. [Giveon Cornfield, prod.] ORLON ORS 78288, $7.98.

Orion continues its attention to Ernst Krenek. one of the most prolific: composers of the twentieth century. (The liner notes inform us that his output, which now numbers well over 2(51 works. already includes eleven operas. three ballets. incidental music for seven plays. five symphonies. four piano concertos, and eight string quartets!) Orion's third all-Krenek disc contains three relatively recent orchestral works.

The earliest of these. Front Three Mohr! Seven, was composed in 1960. a time when Krenek was very much interested in total serialism. The record jacket reproduces a diagram of the carefully worked-out structure of the piece; but as is so often the case with this kind of music. what the listener hears seems to have little if any relationship to what is indicated. The work strikes me as rather undifferentiated. both structurally and texturally.

More successful is Horizon Circled (1967), which is based-as suggested by the title-on a circular plan that progresses from a state of musical "chaos" (represented by a dense orchestral texture of great contrapuntal complexity) toward a series of brief canons played by solo instruments and then works its way hack to its opening condition. Here the pre-compositional plan produces an analogous. and readily comprehensible, aural result. But the most convincing of these pieces, to my mind, is the most recent: Von vorn herein. composed in thy early 1970s. By this point Krenek had evolved a more intuitive approach to composition. He comments: "The piece was not written from beginning to end. but started at various points. and these isolated elements were later brought into the present context. a manner of composing that I have acquired while working in the electronic medium." In other words, he scents to have given his innate musicality-which is certainly considerable-a freer hand.

Krenek is also represented on Orion's release of three new works for oboe played by lames Ostryniec. His Four Pieces for oboe and piano are short but attractive, and they are written in the same sort of free.

rhapsodic atonal style that to me seems to suit his gifts best. Here Krenek makes use of special playing techniques (multiphonics, double trills. etc.). but these are applied discreetly and are carefully integrated into the overall conception.

Charles Wuorinen's Composition for oboe and piano. written in 1965. Opens with basically sustained and lyrical music: that is then juxtaposed with contrasting segments featuring a faster and more varied surface rhythm. It is not an easy work to grasp as a totality, but it is strong and substantial.

Lawrence Moss's Unseen Leaves. scored for oboe. soprano. and tape. is based on two poems by Walt Whitman. It is a most impressive piece. combining virtuosic parts for the instrumentalist and singer with electronic: sounds in interesting and subtle ways. The tape part is closely integrated--mainly through pitch rather than timbre--with the live music. It also contains spoken segments. during which parts of the two poems are read with slight electronic distortion. The structure of the work. which is divided into two analogous sections (one for each poem). is clear and yet unpredictable. When performed live. Unseen Leaves also incorporates slide projections. The recorded version makes me very curious about what the total effect would be.

The performances of all three oboe pieces are very strong. Ostryniec is a first rate instrumentalist. and he is ably assisted by Krenek and Wuorinen at the piano in their respective works and by soprano Ruth Drucker in the Moss. Drucker is particularly impressive. handling a very difficult vocal part with ease and authority. Krenek conducts all of the works on the disc devoted to his music. Although it is difficult to judge without scores, here I was less convinced by the playing. which seemed a bit tentative at moments.

R.P.M. LECLAIR: Concertos for Violin and Orchestra: in C, Op. 7, No. 3; in A minor, Op. 7, No. 5; in G minor, Op. 10, No. 6. Concerto Amsterdam, Jaap Schroder, violin and cond.

TELEFUNKEN 6.42180, $8.98. Tape: 4.42180, $8.98.

These three violin concertos (from a total of twelve) document Leda stature as a vital link between the earlier baroque-era concerto composers and those of the early classical era. ¡dap Schroder's authoritatively persuasive. powerfully recorded performances with his appropriately not-too-large-sized Concerto Amsterdam--all playing period or replica instruments-testify not only to Leclair's expected mastery of violinistic idioms. but also to his arresting inventiveness and structural strength.

The two works from the Op. 7 set (c. 1737) are still patently in the Vivaldi tradition of fast-movement Hornet lo/tutti alternations. , yet Leclair's thematic motifs already are distinctively his own and his solos ornamented with unmistakably French rather than Italian stylistic elegance. But it's the sixth of the Op. 10 concertos (c. 1744), with its increased freedom from Vivaldian formulas and its undeniable ''classical" symmetries. breadth. and elaborate developments, that imperiously commands both one's respect and admiration.

I realize now how much I may have Hissed by having overlooked two earlier discs of Leclair violin concertos: the Fernandez/Paillard versions of Op. 7, No. 2, and Op. TO, Nos. 2 and 6. once (1964) for Music Guild, more recently Musical Heritage Society MI IS 1880; and the 1972 lodry/Werner versions of Op. 7. Nos. 3. 4. and 6, on both Anion 90611 and Musical Heritage MHS 3163. They're likely to be well worth investigation. Schroder's present program certainty is. R.D.D. MAHLER: Symphony No. 4. For a review, see page 76.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 6, in A minor. Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan, cond. [Cord Garben, Hans Hirsch, and Magdalene Padberg, prod.]

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2707 106, $17.96 (two discs, manual sequence). Tape: 3370 026, $17.96.

Comparisons: Horenstein/Stockholm Phil. None. MB 73029

[...] 82

Solti / Chicago Sym.

Bernstein/N.Y. Phil.

Szell/Cleveland Orch.

Lon. CSA 2227 in Col. M3S 776 or MAX 31427 Col. M231313 Karajan's Mahler Sixth is in many ways the symphony's most impressive recording to date. He scores from the start with a wholly convincing realization of the first-movement marking: Allegro energico. ma non troppo. Even the recordings I have most admired slighted some aspect of that direction: Horenstein and Barbirolli (the latter in his deleted Angel recording) took a slower-than-allegro tempo to project the fateful tread of the death march: the feverish Solti and Bernstein go in the opposite direction, ignoring the "ma non troppo"; Szell's deftly sculpted reading is short on energy. Karajan treats the movement with just the right mix of grandeur and nightmarish intensity.

I could ask for more stress on the alternating ritards and returns to tempo at the end of the exposition (which Karajan repeats, of course), but in compensation the tenutos between bars 360 and 370 receive more than customary attention.

The scherzo is firm, grim, and-in the Horenstein manner--a little unyielding at the trio sections, where the surging Solti and Bernstein make the greatest possible contrast. Karajan may still be a shade uneasy with Mahler's mincingly bittersweet side, which Szell captured with the utmost subtlety, but his yielding beat does make the grotesquely pathetic final pages sound with full effect. Karajan slights neither the rarefied delicacy nor the fullthroated passion of the Andante, admittedly a hard movement to spoil.

In the crushing finale, he again steers a fine middle course between the rigorous steadiness and majestic breadth of Horenstein and the more exhausting, theatrical exaggeration of Solti and Bernstein. Even Karajan's liberties--e.g., the cellos' legato phrasing and the slow tempo at the poco piu mosso. bars 258-64-make a structural statement: the quiet interlude is distended to maximize suspense before the return of the whirlwind. All that is lacking is the sheer desolation Horenstein brought to the closing brass chorale. In line with the current consensus. Karajan omits the third hammer stroke.

The playing of the Berlin Philharmonic is extraordinary, and DG has done the performance proud. The strings are agile, velvety, and pure. The woodwinds are developing the wry, surrealistic sound I have missed in Karajan's earlier Mahler recordings. and the horns are magnificent. I am delighted with the generous observance of glissandos. (So why not the one in the solo violin part at bars 118-19 of the Andante?) No Mahler Sixth in the catalog has more clarity than this one, but without the conspicuous spotlighting of detail in the Solti, Bernstein, and even Horenstein recordings; I find the balances most discreet, the overall perspective robust and persuasive.

Horenstein’s Stockholm Philharmonic cannot compare with the Berlin Philharmonic, but his performance retains its special attractions and the Nonesuch price makes it an inexpensive supplement. I would also insist on having a version of the Solti/Bernstein type; between them, Solti has the advantage of Decca/London's polished and plush Chicago sonority, while Bernstein is the choice for those who are attached to that third hammer stroke. Nor would I readily forgo Szell's beautifully contoured reading, despite its comparatively drab sound, audience noise, and omission of the first-movement repeat.

A.C. MOZART: Sonatas for Piano: in F, K. 280; in B flat, K. 281; in D, K. 311; in C, K. 330. Krystian Zimerman, piano. [Wolfgang Mitlehner and Hanno Rinke, prod.]

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2531 052, $8.98. Tape: i 3301 052, $8.98.

Zimerman's exciting debut recording was an all-Chopin program (DG 2530 826, October 1977); for his second record, the young Polish pianist has turned to Chopin's spiritual precursor, Mozart. While these two great composers seem far removed in time and style-one the quintessence of self-denying classicism, the other the embodiment of rapturous early Romanticism-they share, in fact, a similar containment and self-confident perfectionism.

One attribute that made Zimerman's Chopin recital so memorable was his instinct for implicit counterpoint. and it is hardly surprising to find that linear sense and that ear for precise texture equally impressive in Mozart. All four of these sonatas are performed with energy, clarity, and fluency. Ornaments are brilliantly articulated-even verging on spikiness-and runs flow smoothly. The occasional defects are aesthetic rather than technical: one or two overemphatic ritards, a few abrupt-sounding appoggiaturas (the short, before-the-beat one in the minore section of K. 330's slow movement, for example, seems out of character for so lyrical and melodic a passage), an arguably brusque tempo for K. 330's Allegretto finale.

DG's reproduction has greater warmth and richness than the Chopin disc, made on location at the Warsaw Chopin competition using a cold, raw-sounding instrument.

I almost wish it had been the other way around-Mozart would have been less injured by the un-alluring lack of resonance--but Zimerman pedals sparingly, seeming determined to avoid the pianistic equivalent of "Philadelphia Orchestra tone." In this he is close to Peter Serkin, another contrapuntist who manages the Mozart/ Chopin dichotomy outstandingly well.

(Serkin's first Chopin recital disc is forthcoming from RCA.)

H.G. PROKOFIEV: Sonatas for Piano: No. 7, in B flat, Op. 83; No. 9, in C, Op. 103. Tedd Joselson, piano. [Peter Dellheim, prod.]

RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-2753, $7.98. Tape: ARK 1-2753, $7.98.

The deletion of Joseph Kalichstein's fine Vanguard Cardinal performance of the Ninth Sonata leaves the mono Richter recording (MC 2034) as the only single-disc alternative to RCA's new entry; the Seventh. of course, is far more popular, and the catalog shows it.

Joselson further expounds his lyrical view of Prokofiev familiar from his recordings of the Second Concerto (ARL 1-0751. April 1975), the Second and Eighth Sonatas (ARL 1-1570. December 1976). and the Visions fugitives (ARL 1-2158, July 1977). This approach. with its singing tone. poetic colors. and even voicing. proves fully appropriate to the Ninth Sonata's nostalgic, slightly spent rumination. The stormier Seventh, while intermittently well served by similar infusions of nineteenth-century schmaltz, adds up to an expert but incomplete statement. Joselson's playing is not forceful enough to divert attention from the caustic performances of Horowitz (in RCA LM 6014) and Gould ( Columbia, deleted) or pointed enough to challenge the linearity of Richter (Turnabout TV 34359). The piano sound is rich and appealing, but my copy has a lot of crackle.

RACHMANINOFF: Works for Piano and Orchestra. Abbey Simon, piano; St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, Leonard Slatkin, cond. [Marc Aubort and Joanna Nickrenz, prod.] Vox OSVBX 5149, $11.98 (three OS-encoded discs, manual sequence). Concertos: No. 1, in F sharp minor, Op. 1; No. 2, in C minor, Op. 18; No. 3, in D minor, Op. 30 [from Turnabout OTV 34682, 19771; No. 4, in G minor, Op. 40. Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43.

As an inexpensive edition of the Rachmaninoff concertos-or even independent of price-the Simon/Slatkin set has its attractions. Not the least of them is the crisp sound; admittedly this is not concert-hall realism (one would never hear such instrumental detail without the production team's helping hand), but the clarity has the salutary effect of letting fresh air into Rachmaninoff's sometimes musty orchestral room. This music, which so often verges on nebulousness, becomes much firmer of outline. more stimulating intellectually, when instrumental comments are unambiguously stated rather than diffidently mumbled.

Simon is a virtuoso executant, and his assured finger work is tastefully phrased, transparently articulated. Sometimes he seems ever so slightly dis-involved. and particularly in the Third Concerto he shifts gears at emotional climaxes instead of meeting the challenge with a sense of risk.

But one always has the impression that the music is in knowing hands-Simon has been playing it for many years. (He made an excellent mono recording of the Paganini Rhapsody for Epic with the late Willem van Otterloo.) In the Third Concerto, Simon uses the shorter cadenza in the first movement and makes the second "standard" cut in the third movement (from two bars after No. 52 to No. 54). H.G. ROSSINI: Lltaliana in Algeri.

Elvira Zulma Isabella Lmdoro Taddeo Mustald Haly Norma Palacios-Rossi (s)

Gghala Capun (s)

Lucia Valertim Terrani (ms)

Lgo Benelli (t)

Enzo Dara (bs-b)

Sesto Busc:anbni (bs-b)

Alfredo Masotti (bs)

Volker Rohde, harpsichord; Dresden State Opera Chorus, Dresden State Orchestra, Gary Berlin., cond. ACANTA JB 22 308, $26.94 (tiree discs, manual sequence; distributed by German News CO.).

VERDI: Rigoletto.

Glide Marghenta Rmaldi (s)

Countess Ceprano Maria Coreili (s)

A Page Silvia Pawlik (s)

Maddalena Vionca Cortez (ms)

Giovanna Ilona Papenthin (ms)

Duke of Mantua Franco Bonisolli (t)

Bursa Henno Garduhn (t)

Rigoletto Rolando Panerai (b)

Marullo Horst Lunow (b)

Count Monterone Antonin Svort (b)

Sparafucile Bengt Rundgren (bs)

Count Ceprano Peter Olesch (bs)

Dresden Stale Opera Chorus, Dresden State Orchestra, Francesco Molinari-Pradelli, cond. ACAN-A HA 21 474. $26.94 (three discs, manual sequence; distributed by German News Co.). VERDI: II Trovatore.

Leonora Leontyne Price (s)

Azucena Elena Obraztsova (ms)

Ines Maria Venuti (ms)

Mannco Franco Bonisolli (t)

Ruiz. A Messenger Horst Nitsche (I) Count di Luna Piero Cappuccilli (b)

Ferranco Ruggeri) Raimondi (bs)

An Old Gypsy Martin Egel (bs)

Deutsche Oper Berlin Chorus, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan, cond.

[Michel Glotz, prod.] ANGEL SCLX 3855, $24.98 (tree SO-encoded discs, automatic sequence). Tape: 4X3X 3855, $24.98.

DONIZETTI: La Favorita.

Ines Leonora Fernando Ileana Cotrubas (s)

Fiorenza Cossotto (ms)

Luciano Pavarotn (t)

Don Gasparo Piero de Palma (t)

Alfonso XI Gabriel Bacquier (b)

Baldassare Nicolas Ghiaurov (bs)

Chorus and Orchestra of the Teatro Comunale ( Bologna), Richard Bonynge. cond.

[Christopher Raeburn, prod.]

LONDON OSA 13113. $23.94 (three discs, automatic sequence). Tape: OSA5 13113, $23.95.

Two of these four recordings provide reasonable rep osentat ions of the works: if you assume that they're the major-label productions. guess again.

Neither of the Acanta sets displaces the competition, but both can be listened to with pleasure-and both feature distinguished assumptions of the title role. The surprise (fur once a happy ono!) is Rolando Panora i's Kigoletto. probably the best thing this fine if uneven artist. now fifty-four. has clone in his quarter-century recording career. At no point in that career would Panerai have figured on anyone's list of elite vocalists. Ilis virtues. when he's on form, have always boon the less spectacular ones: not a dazzling. wide-ranging instrument, but. at its best, a warm. ingratiating one, limited on top: not a histrionic inflector of the Cobhi sort, but an interpreter capable of considerable emotional force in his sensitive. straightforward way.

All these virtues come together in his Rigoletto. which captures him in his very best vocal estate. 'the often problematic vibrato is under firm control: the line is smoothly maintained. precisely colored: the declamation is surprisingly potent (note the "Cortigioni"--after the sensational "Lo r8. la air" recitative-and the "Si. vendelto"). Everything is delivered without posturing. in Panerai's gorgeous Tuscan Italian-the clarity and beauty of his verbal articulation make the first duet with Cilda extraordinarily touching. Not t he definitive Rigoletto. but a lovely piece of work.

So too is Lucia Valentini-Terrani's Isabella in I,'!taliono in AIegeri (her Met donut role some seasons back). although her balance sheet reads somewhat clifferently: Although somewhat neutral in personality, her vocalism is altogether remarkable. rich and firm from top to bottom. She stands up well to her formidable predecessors-the chest register being fuller and inure easily integrated than Teresa Bergannza's (in the London recording, OSA 1375), the voice as a whole more fluid than Giulictta Simionato's (in the old EMI recording, available as an Italian import. 3C 163 0 981/2 )

L'Itolionu is better served by its conductor than Rigoletto: Gary Bertini keeps things moving nicely. although his work is less vivid than Carlo Maria Glut ini's (EMI). less stylish Ihan Silvio Varviso's (London). The London set remains the logical first choice (EMI's heavy cuts remove it f onn direct competition: the two stereo sets are lightly, and dillerently, trimmed), since it also has a stronger supporting cast and includes full texts. as against Aca Ma's synopsis only.

Acanta's Ugo Benelli is an engaging Lindoro, but London's Luigi Alva is less wispy in tone: EMI's Cesare Valletti combines their virtues. A pity that Sesto Bruscantini didn't record Mustafai in the Fifties when he did such basso buffo roles as Don Pasquale and Ilulcamara: even now. in his more brrritonal and more venerable state (he will be sixty in December), he gives a lively and often vocally pleasing performance. but I prefer London's Fernando Corena. I'd love to hear Enzo Dara as Mustafá rather than Tackled. which really lies too high for a bass-Panerai ( London) was just right.

Acanta's Elvira and /.ulna are on the weak side.

In addition to Panerai, Acanta's Higoletto has in Margherita Kinaldi an above-average. Glide. Unlike most coloraturas. she actually becomes more secure above E. which enables her to sing a fine "Caro nonce." The Duke exposes Franco flonisolli's technical crudity-often misdiagnosed, it seems to me. as simple insensitivity-less severely than Manrico does (see below). and there are strikingly good moments. like his forceful, insinuating attempted seduction of Countess Coprano. Bengt Rundgren is a first-rate Sparafucile (complete with foreign accent, even if it is not quite borgognone). Viorica Corti-ha satisfactory, Maddalena. Antonin Svore a dreadful Mont crone.

The balance of the cast is okay, as are the Dresden chorus and orchestra under the uninspiring Francesco Molinari-Pradelli, who in his third Higuletto recording still declines to give the score uncut. In fact, he has backslid a bit, re-introducing the "Addio, sperunzo solo soroi per me" cut at the end of the Gilda/Duke duet. Otherwise the text follows his Angel recording. with two small "standard" excisions in the first Gilda/ Rigoletto duel (the seven repetitive bars before "II nnnte. vostro (tinfoil' :and. infuriatingly. the six lovely and non-repetitive bars near the end) but not the frequent major cut in the "Veglio o donna" section, which Molinari-Pradelli made in his earlier Columbia recording. As in the Angel recording, one stanza of "Possente omor'' is included--rather well sung by Bonisolli.

Molinari-Pradelli surely deserves credit for getting plausibly Italianate. if hardly idiomatic. work from the Dresden forces: Herbert von Karajan doesn't seem even to have made the effort in his Berlin '1'rovatore. This recording demands to be heard by anyone who cares about either the opera itself or the genre: If you want to understand, for example. the emotional logic of the standard double--aria form, listen to the astonishing rhythmic propulsion Karajan generates in all the ca ba letlas-and at ratherstowternpos; t new performance is in general slower than his La Scala mono recording with Maria Callas (Angel 5sL 3554). hut temperamentally they are surprisingly close. Still. for all karajan's grasp of the score's sense of movement and Balance. the actual sound of the orchestra (anal chorus) is so wildly wrong (as in his hilarious set of Verdi overtures and preludes. DG 2707 090) that I am unable to listen with any real pleasure.

There's little to please in the singing.

Leontyne Price's new Leonora is more specific interpretively than her RCA recordings. but the voice is no longer consistently up to the music's uncompromising demands: below the break in particular there is now nothing but heavy breathing stretched, at karajan's tempos. to painful limits. Elena Obt'nurtsova reverses today's usual Az.ucena pattern: She has power aplenty below the break but goes wild on top. (The "Stride lo vompa" and "Condotta ell'era" on her recent Angel recital disc. S 37501, are far better controlled.) Bonisolli's inability to rise reliably above the break makes his Manrico an in-and-out affair, which is still more than Piero Cappuccilli can manage-his Di Luna, muddy in texture and gray in color, is strictly out. Ruggeri)

Raimondi's high-lying bass ought to suit Ferrando well, but he never gets beyond note-rendering. The recording is complete . but I cannot recommend it over the solid uncut RCA set with Price, Cossotto, Domingo. Milnes. and Giaiotti, conducted by Mehta (LSC 6194). Karajan's Trovatore at least has Karajan: London's Favorite has nothing. Fiorenza Cossotto sings well but makes virtually no effect. at least in part because the voice lacks strength below the break. Gabriel Bacquier's shrewdness gets him through Alfonso (which does not lie high as written) but without any suggestion of the vocal splendor required for one of the centerpieces of the bel canto baritone repertory.

Luciano Pavarotti is locked into a gummy croon: Nicolai Ghiaurov is in the sad form of recent years. which means an insufficient top and bottom for Baldassare: Ileana Cotrubas sings the small but difficult role of Ines awfully. Richard Bonynge's conducting is an undifferentiated blur, and so is the recorded sound.

We do hear music-notably the tenor cabaletta that ends Act 1--omitted from previous recordings, but the whole enterprise adds up to a misrepresentation of the opera. I see no point in discussing its complex textual problems; for that, readers are directed to Andrew Porter's New Yorker review of last season's Met production. For this recording. some unspecified hand has considerably modified the standard jannetti translation of the original French libretto, presumably to bring the Italian text into closer conformity with Donizetti's original musical line. But the plot remains garbled, and the chaos is compounded by London's booklet, which gives a plot synopsis of the original version--"to save confusion"! Favorita is a remarkable opera in its own right, and it must have made an enormous impression on Verdi--as reflected particularly in his four "Spanish" operas, above all the first and last of them. Ernani and Don Carlos. (The structural parallels between Favorite and Don Carlos are eerie.) Even Boito must have had the majestic brass chorale at the beginning of Act IV in his ears when he wrote the prologue to Mefistofele. The recording that contains the strongest hints (though hints they remain! of Favorita's stature is the old Cetra with Fedora Barbieri, conducted by Angelo Questa.

K.F. B SHCHEDRIN: Concertos for Piano and Orchestra: No. 1; No. 3. Rodion Shchedrin, piano; U.S.S.R. Symphony Orchestra, Yevgeny Svetlanov, cond. [Igor Veprintsev, prod.]

WESTMINSTER GOLD WG 8359, $3.98.

B SHCHEDRIN: Symphony No. 2. Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, cond. [David Gakin, prod.] WESTMINSTER GOLD WG 8357, $3.98.

The immensely talented young Rodion Shchedrin (b. 1932) wrote his exuberantly virtuosic First Piano Concerto in 1954 for his graduation from the Moscow Conservatory and went quickly on from there to compose prolifically. There are many chamber and piano works, a First Symphony (1958), and a flood of theatrical works, some of which-particularly the strings--and-percussion ballet metamorphosis of Carmen themes--won almost immediate international renown. But evidently that wasn't enough. Yearning to join the musical avant-garde elite. Shchedrin labored long and hard over such credentials as the pretentiously big and demanding Second Symphony (1962-65) and the no less tumultuous Third Piano Concerto (1975). Despite their ambitious "progressiveness." both of these works were approved for recording in Russia. and they well may represent just how far (or short) into modernity the Soviet Musical Establishment permits its composers to go nowadays.

Actually, Shchedrin--like some other Russians in other fields--misses the bus by a good many years: His modernity is little more than that of the Twenties in the West.

The jacket notes stress his discovery of the "methods of aleatorics," but as best as I can tell he makes only passing, minor use of this technique. And his claimed "amalgamation of aleatory, dodecacaphony, and polytonality" strikes me as unmistakably old-fashioned had-boy, wrong-note but essentially tonal jeux d'esprit. No less vieux jeux are the cliché endings of both the concerto and the symphony with the same motifs that began each work. The strongest influences evident are Liszt at his most Mephistophelian and Sibelius keening over dark. passionate doings in the thickest Finnish forests, here translated into vast, storm-swept Siberian steppes. Even the seeming architectural novelties-the complex linking of extended variations in the Third Concerto, the intricate mosaic-structuring of twenty-five "preludes" in the Second Symphony-must be more apparent to the eyes of a score reader than to the ears of a listener.

To give Shchedrin his due ... he is a prodigious inventor of musical ideas and sound effects (especially percussion). And if his often sheerly frantic fury commands wincing attention rather than willing admiration, it inspires his conductors and players to superhuman efforts (of a piece with his own uninhibitedly bravura piano playing). all captured in ultra-powerful and ultra-vivid. if hard-and sharp-toned Melodiya recordings.

R.D.D.

Shostakovich: Symphonies: No. 4, in C minor, Op. 43; No. 5, in D minor, Op. 47. Chicago Symphony Orchestra, André Previn, cond. [Christopher Bishop, prod.] ANGEL S 37284 (No. 4) and S 37285 (No. 5). $7.98 each SO-encoded disc. Tape (No. 5 only): 4XS 37285, $7.98.

Comparisons-No. 4: Ormandy/Philadelphia Orch.

Kondrashin/Moscow Phil.

Comparisons--No. 5: Previn/London Sym.

M. Shostakovich/U.S.S.R. Sym.

Col. MS 6459 Mel./Ang. SR 40177 RCA LSC 2866 Mel./Ang. SR 40163

In the Fourth Symphony, completed in 1936, Shostakovich made his first real attempt since the First Symphony (1926) to write a "normal" symphony-the single-movement Second and Third could both easily he designated by some other title--yet even it might better he called a "concerto for orchestra," so brilliantly are its huge orchestra's facets highlighted.

Shostakovich retained that big orchestral sound in the Fifth Symphony (although the actual forces are nowhere near as extensive; the brass disappears altogether in the third movement) but returned to the formal tightness of the First. Perhaps even more important, it was with the Fifth that the composer, no doubt discouraged by obstacles his theatrical works had encountered, transferred to the symphony the dramatic sense that pervades his 1934 opera Lady Macbeth of Mzensk. Despite the symphony's heroic finale, the work as a whole, like Lady Macbeth, stresses tragedy over triumph and. in the second movement. satire over good will.

André Previn's is only the third recording of the Fourth since the composer finally released the work late in 1961. Although the symphony's first two movements have an acerbic brilliance rarely found in quite the same form in Shostakovich's later works, and although the sepulchral closing-celesta over sustained strings--has a devastating impact after all the preceding pyrotechnics, the work has never caught on.

This may be because of its length (over an hour), or perhaps because audiences find it too abrasive (while critics wish it were more so). Previn's interpretation, which brings the work's jolting clashes into strong relief, is not apt to win more fans. Pleased as I was to hear with clarity exactly how Shostakovich sets up his shocks in the contrapuntal and instrumental textures, one's reaction should go much deeper. The dramatic effectiveness of Shostakovich's music depends more often than not on a sense of flow. Each musical figure must get out of the way in time to make room for the others, and Previn frequently does not allow this to happen, especially in the key first movement. To me, the Ormandy recording represents a satisfying compromise between Previn's performance and Kondrashin's virtuosic one, which flows too much.

Sonically, the new Angel disc does not measure up to either of its predecessors.

Previn's remake of the Fifth seems to me less satisfactory in both interpretation and sound (at least in the Angel edit ion) than his earlier recording, with the London Symphony for RCA. Indeed the latter impresses me on rehearing as very nearly the equal of the recording by the composer's son.

Maxim. Previn's better-balanced, livelier finale does the music more justice than Shostakovich's; only the latter's added incisiveness in the first movement leads me to rank it first above Previn's.

The new Fifth differs in subtle but important ways from Previn's RCA version.

Where the latter is notable for its sharp attacks and crisp, no-nonsense phrasing, the Angel sounds slightly flabby-note the matter-of-fact opening bars. In addition. entrances often (especially in the first movement) seem just momentarily early, as if the Chicago Symphony were champing at the bit. The violas occasionally indulge in some wobbly vibrato, while the solo violin neglects some important glissandos in the second movement, in which Shostakovich came perhaps as close as he ever did to sounding like Mahler. Previn also eschews most of the rubatos used to good effect in the earlier recording.

Questions of interpretation aside, I find the RCA version, with its bright highs and rich bass, sonically superior to the more homogeneous Angel, my copy of which also has considerable surface noise and roar.

R.S.B. STRAUSS, J. II (arr. Dorati): Graduation Ball.

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Antal Dorati, cond. [James Mallinson, prod.]

LONDON CS 7086, $7.98. Tape: CS5 7086, $7.95.

Comparisons: Dorati/Minneapolis Sym. Mer. SRI 75014 Boskovsky/ Vienna Phil. Lon. Treas.

STS 15070 Graduation Ball is one of a small group of "metamorphosed" (arranged and synthesized by other than the composers) ballet scores that irresistibly enchant novice anti connoisseur listeners alike. It's also one that. despite enormous popularity both on the stage and in earlier recordings. hasn't been kept as up to date on records as it should be. (We've had no recent versions at all of the Boccherini-Frangaix Scuola di bollo, Scarlatti-Tommasini Good-Humored Ladies, and Handel-Beecham Love in Both.) Even Dorati's own Minneapolis recording. brought back a few years ago in the Mercury "Golden Import" series, not only dates hack to 1957, but is brutally cut. Nor is the well-liked Boskovsky/London version, now some seventeen years old, absolutely complete: Like all recordings before the new one, it omits No. 4 of the Divertimentos, the bubbling "Virtuoso Polka" that begins Side 2 of the present disc. Yet completeness and up-lo-date audio technology aren't the most magnetic attractions here. Dorati and the Vienna Philharmonic are in fine form, losing not a drop or bubble of this effervescent tonal champagne.

Dorati's jacket notes are mainly concerned with the "story" of the staged ballet, but he does correct an error made by earlier annotators. who claimed that the musical materials came from unpublished Strauss scores. Now the sources are described as little-known (but published) scores obtained "from a Viennese antiquary." Dorati also explains the slight textual differences in various recorded versions by noting that the original manuscript, lost for a time. was rewritten before it turned up again. The present performance is of a "combination of the existing versions, going hack to the original orchestration of the Grand Galop," etc.

R.D.D.

STRAVINSKY: Oedipus Rex.

Narrator Jocasta Oedipus The Shepherd Creon The Messenger Tiresias Alec McCowen (spkr)

Kerstin Meyer (ms)

Stafford Dean (bs)

John Alldis Choir, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Georg Solti, cond. [James Mallinson, prod.]

LONDON OSA 1168, $7.98. Tape: OSA5 1168, $7.95.

Comparisons: Bernstein/Boston Sym. Col. M 33999 Stravinsky/Cologne Radio Odys. Y 33789 Stravinsky/Washington Opera Col. M 31129

Proficient though Solti's marshaling of his excellent choral and orchestral forces may he, this recording yields up something less than the full impact of Stravinsky's monumental score. Both playing and singing are all too often bland. sometimes--in dotted rhythms. for example--even a shade slack.

The major exception is Peter Pears, still an Oedipus of great imagination and intensity-but also of much diminished vocal powers by comparison with his work of twenty-five years earlier, on Stravinsky's Cologne recording. Then the voice could ring out to represent "Clarissimus Oedipus": now we sense that, however artful, this is an elderly Oedipus. and even Kerstin Meyer's perhaps maternal tremolo is insufficient to right the dramatic balance. Otherwise among Solti's soloists. I admire Donald McIntyre's firm Creon; Stafford Dean's Tiresias is on the woolly side, and the others are creditable. Alec McCowen's narration is straightforward and vigorous, avoiding the supercilious tone adopted by Michael Wager for Bernstein's recording.

That recording, though less idiomatic than either of Stravinsky's (and unevenly sung to boot), is certainly more committed than Solti's. Still, the composer's versions have the most flavor and impact: I would go first for the mono Odyssey. with Pears at his greatest. Martha Módl a disturbingly ripe Jocasta. and Heinz Rehfuss the solidest of Creons: Cocteau himself recites his narration. with great relish. and the sound is still remarkably fine. Unlike all the full-priced versions. Odyssey offers no text or translation.

D.H. TELEMANN: Works for Oboe. Heinz Holliger, oboe; Christiane Jaccottet, harpsichord; Nicole Hostettler, spinet; Manfred Sax, bassoon; Philippe Mermoud, cello.

PHILIPS 9500 441, $8.98.

Partita for Oboe and Continuo, in G minor. Solos (Sonatas) for Oboe and Continuo: in E minor, in G minor. Sonata for Oboe, Harpsichord, and Continuo, in E flat.

B TELEMANN: Works for Winds. Samuel Baron, flute; Ronald Roseman, oboe; Arthur Weisberg, bassoon; Timothy Eddy, cello; Edward Brewer, harpsichord. [Marc Aubort and Joanna Nickrenz. prod.] Nonesuch H 71352, $4.96.

Sonatas: for Oboe, Harpsichord, and Continuo, in E flat; for Bassoon and Continuo. in F minor; for Flute and Continuo, in C minor. Quartet for Bassoon. Flute, Oboe. and Continuo. m D minor Here are a couple of treasure troves to warm the heart-cockles of all Telemanniacs and oboists. They're also persuasive testimony both to Georg Philipp Telemann's inexhaustible creative inventiveness as a composer and to his delectable geniality and humor as a man. Listening to the extraordinary variety of attractions here. one has no difficulty in Linde standing the high musical and personal esteem in which Telemann was held by his contemporaries--including Bach and Handel.

In general the Philips performances are in the nature of concert-hall presentations dominated. both tonally and in personality projection. by the incomparable Heinz Holliger. And they are the more closely miked in vivid-presence recording. The Nonesuch program (like earlier ones featuring Ronald Roseman. one of the finest American oboists and program-makers) is a truer chamber music presentation. more equably balanced. less extraverted. and less closely yet brightly recorded. Only one work-the remarkable E flat Trio Sonata (Esercizii musici No. 12)-is common to the two programs. and the treatments are so distinctively individual and yet equally admirable that only a foolhardy critic would proclaim one "better." (Perhaps there should be special praise for the ingenious use of a spinet in the Philips continuo part.) The rest of each recording is no less praiseworthy. Philips provides more oboe-starring vehicles: an unusually constructed partita from the Kleine Kammermusik collection: one of the Esercizii rnusici "solo' sonatas: and the G minor Sonata from the third production of the Musique de table.

Nonesuch explores a wider range of woodwind vehicles: a jaunty bassoon sonata from Der get retie Musikmeister; No. 8 of the "methodical" flute sonatas (the one with the charming Ondeggiundo movement): and. perhaps most substantial and rewarding, the arresting quartet from the second production of the Musique de table. in which the bassoon is primus inter pares.

In this or any month there are few releases that, heard first as a reviewer's duty, demand as insistently immediate and innumerable re-playings simply for personal pleasure.

R.D.D.

THOMAS: Mignon.

Phióne Mignon Frédénc Wilhelm Meister Latirte Jarno Lothano Antonio Ruth Welting (s)

Marilyn Horne (msl Frederica von Stade (ms)

Alain Vanzo (t ) Andre Battedou (t) Claude Meloni (b) Nicola Zaccaria (bs)

Paul Hudson (bs)

Ambrosian Opera Chorus, Philharmonia Orchestra, Antonio de Almeida, cond. [Paul Myers, prod.] COLUMBIA M4 34590, $31.98 (four discs, automatic sequence). Ambroise Thomas (Itt11-96) was a respected but hardly famous French composer and teacher until, in 1866, he hit the jackpot with Mignon. He followed its success two years later with another hit, I loinlet--recently revived by the San Diego Opera for Sherrill Milnes-became director of the Conservatoire in succession to Auber, and lived out his long life largely on the reputation (and performance income) from these two works.

Mignon, once a Metropolitan Opera staple, is a melodic number opera at the core of the French nineteenth-century operatic style. The lilting music strikes me as more balletic than operatic (it is curious that the ballets Thomas wrote are forgot, ten) in that its soft-contoured melodies are shaped with a plasticity and elegance of phrasing less robust titan the lyricism of Gonna(' or Bizet. This attention to expression through phrase and dynamics would later, of course. be a feature of Massenet's style. although here it is more classically restrained. Thomas the pedagogue is always the musical professional, but his best moments in the sco e lie in the justly remembered solos. which have a lyrical spontaneity and a characterizational felicity both evocative and memorable.

The libretto. which interestingly enough had in some form been offered a few years earlier to Meyerbeer, is based on Goethe's Wilhelm Meister, but as fashioned by Bar bier and Carré the tale becomes a series of excuses for "numbers." Certainly the plot--the half-crazed, wandering minstrel: the frail. narcoleptic waif: the hard-bitten actress: the handsome young student--is the stuff of operatic parody. particularly when the old minstrel turns out to be the waif's father.

Mignon exists in several versions. It was originally composed for the Opéra-Co mimic. with spoken dialogue and an elaborate final act (built on a theme used as the coda to the overture). Thomas recomposed the ending into a simpler finale, dropping the tune. For the London production of 1870 he made further changes. which included adding a very empty showpiece aria for the actress Philine and, after reworking the buffo tenor role into a more sympathetic trouser role, using the aria "Me voici duns son boudoir" from the second-act entr'acte.

For German audiences, he made a short, unhappy ending in keeping with Goethe.

The present recording is of the "standard" score, with some elaborations and recitatives replacing spoken dialogue (a pity, since Thomas made extensive use of the very dramatic convention of melodrama--spoken words over music). Carried as an appendix on the eighth side are the second Philine aria and the whole of the discarded first finale.

The performance is a generally good account, its major fault being the excessively reverberant sound. ('I'he recording was made in All Saints' Church. Tooting.) Little of Thomas's felicitous orchestration can be heard, and the chorus is not defined sharply enough (indeed, the oft-stage barcarolle in Act III sounds as if it came from Venice). The miking of the singers is such that their voices often cover the accompaniment.

Conductor Antonio de Almeida obtains a good measure of phrasing and elegance. but again. perhaps because of the recording, the music wants greater crispness of attack (particularly from the chorus), more clarity in the ensembles.

Celestine Galli-Marié (later to be the first Carmen) was twenty-six when she sang the title role in the premiere of W. ignon, and Marilyn Horne is not. She tries to make her voice sound as youthful as possible and invests the role with her usual éclat (now and then taking the soprano variants indicated in the score: the role is intended to be sung by either voice). Yet her voice is simply too large and lacks the freshness and naiveté it should have, particularly in the slow tempo chosen for "Connais-tu le pays?," which suggests the wisdom of maturity rather than the wonder of innocence.

Alain Vanzo has long been an underrated French tenor, but his voice is now past its prime, and his many years of performing heavier tenor roles have robbed the voice of the refined yet ardent lyricism it should have for the role of Wilhelm. His general inability to sing much below forte tells against him, and he mistakenly sees "Adieu, Mignon, courage" as it sobby, sentimental ballad instead of the tenderly regretful moment it is. Nonetheless, the strengths of his French pronunciation and his still lovely voice are major assets.

Ruth Welting negotiates Philine's music with bravura, if not ease sounding hard and brittle: she too hugs the fortes at the expense of any other dynamic. Frederica von Stade is excellent in the small role of Frederic, and Nicola Zaccaria is a rather gruff, spread-toned Lothario.

P.J.S.

VERDI: Nabucco.

Abigaille Anna Fenena Ismaele Renata Scotto (s)

Anne Edwards (s)

Elena Obraztsova (ms)

Veriano Luchetti (t)

Abdallo Nabucco' Zaccaria The High Priest Kenneth Collins (t)

Matteo Manuguerra (b)

Nicola' Ghiaurov(bs)

Robert Lloyd (bs)

Ambrosian Opera Chorus, Philharmonia Orchestra, Riccardo Muti, cond. [John Mordler, prod.] ANGEL SCLX 3850, $24.98 (three SO-encoded discs, automatic sequence).

Tape: 4X3X 3850, $24.98.

Comparison: Souliotis. Gobbi, Cava. Gardelli Lon.

OSA 1382

A Nubucco with Maria Callas as Abigail and Ettore Bastianini in the title role remains one of the might-have-beens, the would-that-there-had-beens. of recorded history. Callas sang the role only in 1949. in Naples. In dim and distorted sound, with squeeze-box orchestral tone and, in the death scene, quality to suggest that the recording was made by Lionel Mapleson, perched in the flies with his cylinder machine, the Naples performance has been published in Cetra's Opera Live series and also in Vox's Turnabout Historical Series (see David Hamilton's discussion, in this issue. of the Callas historical releases). It is a "document" that historians of the diva may wish to study--perhaps "decipher" is the word-but it cannot be taken seriously as a recorded account of Verdi's first success.

For that account, a Cetra set conducted by Fernando Previtali--an Italian Radio performance that inaugurated the 1951 Verdi commemoration-had for many years to serve. It had spirit, especially in its heroine. Caterina Mancini. and had some impressive passages from Paolo Silveri in the title role. But it was rough. and no more than a stopgap. In 1966 there came the London issue (OSA 1382). which Conad L. Osborne in September of that year called "a performance that at least discloses the basic qualities of this interesting opera, and that is recorded beautifully enough to make even the more unfortunate moments still listenable." Now, twelve years later. there arrives a competitor. I find it hard to choose between them. In a summary comparison. I would suggest that while some things about the new Angel are brighter and better, the London set still "discloses the basic qualities" of the opera more accurately. The Angel, however. is the first complete Nubucco. In the London album, the protagonist omits ten and then sixteen measures of his most difficult music.

When Benjamin Lumley introduced Nohucco to London, in 1846 (it was disguised as Nino. He d'Assirio, and the Jews became Babylonians). he wrote of his prima donna, Giulia Sanchioli, that, "wild, vehement, and somewhat coarse, she attracted by power, spirit. and fire .... As a declaiming, passionate vocalist, she created an effect 'the right woman in the right place' in this melodramatic opera." In a similar way, Elena Souliotis creates an effect in the London recording. She has power, spirit, and fire-but she lacks delicacy, another quality that an Abigail needs. The Angel set presents Renata Scotto at her spunkiest, but she is also delicate.

In temperament and vocal weight, one might think that the casting director had got the two ladies--Scotto as the formidable spitfire Abigail. and Elena Obraztsova as the gentle. lyrical Fenena-the wrong way round. Not in range. of course. Fenena is a soprano role often take by mezzos. and easily compassable by them (in the autograph, there survives Verdi's own "re-pointing" of Fenena's aria for higher voice). while Abigail is indisputably a soprano part, with several important high Cs. (Tb: Cetra/ Turnabout set preserves, even through the awful recording. some of the firmest and easiest high Cs Callas ever put on disc.) Some of Scotto's highest notes take on that squealy quality that her voice acquires when she forces up the pressure: and down below, some of the weighted chest tones are exaggerated. But energy. spirit. and conviction mark her performance. and there is much strong. accurate singing. Like all her work. this is carefully and thoughtfully prepared. with a real sense of what she wants to express and how best to express it: and it is never mannered or self-indulgent in the clay that her singing can be when she performs with a conductor more permissive than Riccardo Mid i is. I ter treatment of coloratura--of ' he "Costa Di vu"--like filigree spun round the line of "Atich'io dischinso un giorno"--is particularly admirable: she doesn't flick through it but gives it full dramatic value.

The first exchanges of Penena and Ishmael (Veriano Luchetti) sound absurd; they bawl out their intimate declarations. Queen Victoria complained of Mr. Gladstone that "he speaks to Me as if I was a public meeting." This Fenena might say the same of her Ishmael; and then she answers right back in the same manner. Luchetti continues in that vein throughout. In ensembles, he seems convinced that the tenor always has the tune. In the first finale, where Fenena and Ishmael join in octave phrases marked piano, ít sounds as if they were in full voice but have been subdued by the sound mixer.

Fenena's cantabile preghiera, "Oh dischiuso it firmamento," is, however, smoothly and sensitively sung. All the same. I regret that a sweet lyric soprano was not chosen for the role. Gabriella Gatti, a Desdemona, does it, and does it well, on the old Cetra recording.

But Fenena and Ishmael are subaltern roles. Abigail. Nebuchadnezzar, and Zechariah (to use the familiar Biblical spellings) must carry the weight of the opera. Matted Manuguerra was an interesting choice for the title role. (Originally Sherrill Milnes was announced for it. and later Piero Cappuccilli.) A decade or so ago, Manuguerra proved his Verdian merit as the Posa of a French Radio performance of Don Carlos (a tape of which supplies ammunition for those who believe that Carlos sounds best performed in the original language). In Nabueco, he compasses all the part in a well-schooled baritone of excellent timbre. And yet--here, as in his various Met roles--he seems to lack some force of personality.

Tito Gohbi (in the London set) recorded the part late in his career, and Osborne found him "leagues away from the suavity and beauty of tone and line that is a necessary ingredient of the role." But reaction to Gobbi has always been personal, and diverse. I find him commanding. strongly characterized, and powerful-more of a king, and more of a Verdian character, than many baritones able to vocalize the music more easily: more arresting than Manuguerra. The latter's idea of sotto voce. when launching the first-act finale, is not mine.

Nicolai Ghiaurov has recorded Zechariah's three solos before: the cavatina and profezio on London OS 26146, the preghiera on OS 25769. The voice now is not guile the grandly sonorous organ it was then. In the cabaletta of the cavatina there is a tendency to coo notes that were once firmly struck. The preghiera is swig with grave, smooth beauty of tone, and yet there is a quality that might perhaps be described as "cavernous." Of course, one is measuring Ghiaurov against standards he himself set.

It is still a noble, impressive performance, one of the finest things he has put on record in recent years, and much more the real thing than London's Carlo Cava.

On the recital disc. as in the opera, the profezio is preceded by the fatuous chorus "Va, pensiero." It is conducted there by Claudio Abbado. And that brings one to discussion of the conducting of the new Angel set. Muti might be considered at once the main strength and the main drawback of the new version. On the credit side, he secures-from his own orchestra. the Philharmonia-playing of extraordinary power, beauty, and precision. The textures are limpid. For example, I doubt if the busy bassoon writing under Zechariah's cabaletta can ever before have been heard so clearly as it is here. One is made aware of every detail of the scoring. In long choral or long instrumental lines there is also uncommon beauty of tone and beauty of phrasing. (The chorus is very good.) And Muti has paid scrupulous attention to all the markings to be found in Verdi's score.

On the other hand ... On the last page of the Angel booklet there is a note headed "A Conductor's Approach," and it contains the defensive statement: "Occasionally Riccardo Muti appears to adopt fast tempi and ... he may not stick rigidly to the indicated metronome marking." Well, there are no indicated metronome markings in Nahucco.

But Muti does adopt fast tempos: again and again, tempos so fast, so unnaturally fast, that the excitement. the urgency of the music evaporate in a virtuoso-e en a vulgar--display.

To the director of the Fenice. in 1842, Verdi wrote: "I would beg you to point out to the conductor that the tempos should not be too broad. They should all move, especially in the canon in the second-act finale." But there is a difference between moving and scampering. In Abbado’s conducting of "Va, pensiero." and in Lamberto Gardelli's conducting of the whole opera (for London), the tempo moves. In Muti's conducting, almost all the fast numbers are rushed.