by Kenneth Johnson and William C. Walker

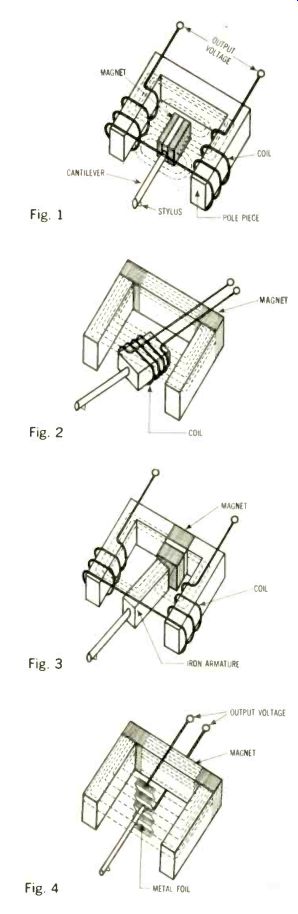

Fig. 1 - Fig. 4

THE PHONO CARTRIDGE is one of the smallest and, in many ways, the least understood of audio components. Despite its diminutive size, the cartridge performs a seemingly impossible task. When picking up tie two channels of a stereo program, the stylus is simultaneously deflected laterally and vertically at frequencies that can exceed 15 kHz, sometimes experiencing accelerations in excess of thirty times the acceleration of gravity. Despite these severe conditions, the stylus must remain in continual contact with the groove walls or blatant distortion will result.

The part of the cartridge that converts the vibrations of the stylus into an output voltage is called the transducer. Many types of transducer systems are available today, each with its own theoretical advantages and disadvantages. Yet designers have discovered ingenious ways to circumvent the problems inherent in each type, and many of them are capable of excellent performance. Regardless of the type of transducer, all high quality cartridges are engineered with the same performance goals in mind: (1) ability to keep the stylus in contact with the groove walls at all times; (2) flat frequency response over the entire audible frequency range; (3) inaudible distortion; (4) a high degree of channel separation; and (5) output voltage and impedance to match the input characteristics of preamps.

Two basic transducer types are used to generate a pickup's output voltage: magnetic and nonmagnetic. Magnetic transducers, which dominate the market, depend for their operation on changing the magnetic flux that cuts through a wire, generally one that has been formed into a coil. Subclasses of this type include the moving-magnet, moving-coil, moving-iron, and (like the Nagatron HV-9100 reviewed here) ribbon cartridges. In the other classes are piezoelectric (ceramic), semiconductor, and electret cartridges, none of which use magnets. Generally speaking, cartridge manufacturers concentrate their efforts on one transducer type for their main product line.

Moving-Magnet Cartridges. The moving-magnet transducer uses a small permanent magnet attached to one end of the stylus cantilever, as shown in Fig. 1. Near the magnet are two coils that usually consist of several hundred turns of wire wrapped around an iron or ferrite core called the "pole piece," which directs the magnetic flux through them.

As the stylus moves, so does the magnet, changing its distance from the coils. When the magnet is moved to the left, for example, the magnetic flux that intersects the left coil increases and the right coil experiences a decrease in magnetic field lines. Voltages will be induced in both coils, although they will be of opposite polarity. By connecting them in the proper manner, it is possible to obtain an output voltage twice that of a single coil. This is typically between 2 and 10-millivolts, a level most preamplifiers are designed to accept. Equally important, using two coils in this fashion greatly reduces the hum and noise picked up from extraneous sources.

Most magnetic cartridges incorporate such hum-bucking coils.

Among the advantages of this kind of cartridge are relative ease of manufacture and convenient replacement of worn or damaged styli.

Moving-Coil Cartridges. Quite similar in operation to the moving-magnet pickup is the moving-coil type, except that the coil is attached to the cantilever and the magnet is stationary, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

As the groove forces the stylus to vibrate, the attached coil also moves and cuts lines of magnetic flux. This action induces an output voltage. In order that the coil not impose an excessive mechanical load on the stylus cantilever (and on the record groove), it must be as light as possible and typically consists of just a few turns of very fine wire. The output voltage is thus very small, necessitating a boost from a special transformer or pre-preamp (head amp) before delivery to a normal phono input.

Moving-coil cartridges are capable of excellent performance and enjoy a certain mystique among hard-core audiophiles. Since their manufacture requires considerable handwork, they are moderately expensive. In most cases, they must be returned to the factory for stylus replacement.

Moving-Iron (or Variable-Reluctance) Cartridges. In this type of design, both the magnet and the coil are fixed, and a small piece of ferromagnetic material (usually iron) bonded to the end of the stylus cantilever is the part that moves (Fig. 3). The means of operation depends on the fact that a magnetic flux can be made to travel in a closed path of magnetic material, much the way an electric current flows through a conductive path. A gap in the path into which a nonmagnetic material--say, air--is introduced adds reluctance (which acts like resistance in an electric circuit) and reduces the amount of flux. The iron fixed to the cantilever moves in such a gap, thus controlling the amount of flux that passes from the permanent magnet to the coils, which are normally connected in a hum-bucking arrangement like that used in the moving-magnet cartridge.

The moving-iron design allows the use of a large permanent magnet and coils with many turns of wire--both of which help to obtain a large output voltage--while keeping the effective mass of the cantilever small. It is relatively inexpensive to build and usually has a user-replaceable stylus.

Ribbon Cartridges. The ribbon cartridge is similar to the moving-coil type in that the extremely light, thin piece of metallic foil attached to the cantilever and the wires connected to the ends of the foil (ribbon) form a coil with one loop (Fig. 4). As the stylus vibrates the ribbon, the area enclosed by the "coil" changes. Since the coil is in a uniform magnetic field, changing its area also changes the amount of magnetic flux and induces a voltage.

This type of transducer has an output voltage similar to that of a moving-coil design, requires a pre preamp, and has similar advantages and disadvantages--and minimum inductance besides. Styli may be user-replaceable, but manufacture is expensive.

---------

(High Fidelity, Jan. 1979)

Also see: