Reviewed by: SCOTT CANTRELL, ABR CIIIPMAN, R. D. DARRELL, PETER C. DAVIS, ROBERT FIEDEL, ALFRED FRANKENSTEIN, HARRIS GOLDSMITH, DAVID HAMILTON, DALE S. HARRIS, PHILIP HART, PAUL HENRY LANG, IRVING LOWENS, ROBERT C. MARSH, KAREN MONSON, ROBERT P. MORGAN, J. NOBLE, CONRAD L. OSBORNE, ANDREW PORTER, H. C ROBBINS LANDON, PATRICK J. SMITH, PAUL. A. SNOOK, SUSAN THIEMANN SOMMER

---------- Lorin Maazel--taking the Cleveland through its second cycle of Beethoven's nine

BEETHOVEN: Sonatas for Piano: No. 4, in E flat, Op. 7; No. 23, in F minor, Op. 57 (Appassionata). Russell Sherman, piano. [Tomlinson Holman and Tom Kusleika, prod.] SINE QUA NON SAS 2023, $6.98 [previously released on ADVENT cassettes E 1057 (No. 4) and E 1060 (No. 23), 1977].

Sherman is a formidable pianist and an interesting musician. He stresses clarity of texture and communicates his ideas with freshness and enthusiasm, though he is not blessed with the gift of simplicity. I occasionally wish for a fuller-bodied sonority, less finicky phrase shapes. less picky articulation: Beethoven can absorb large quantities of personalized concentration. but there are more direct approaches. and certainly more tonally grateful ones.

A few examples from Op 7 should demonstrate what bothers me. The excessively short chords at the end of the first movement and the beginning of the Adagio splinter and disjoint the musical argument: while Beethoven peppers his melodic fragments with telling pauses. one must nonetheless feel an ongoing line. Similarly, the figurations in bars 60 and 62 of the Adagio are given with a contorted robalo. I found the scherzo too slow (it is marked allegro). and though the rondo goes at a fine brisk, unsentimental clip, the tacky left-hand work in the minore section and the fussy ffps in bar 161 are impediments to wholehearted enjoyment.

The Appassionanta displays similar tendencies. but since this sonata is habitually subjected to all sorts of heaving and hauling. Sherman's intellectualized mannerisms sound relatively patrician. He observes all repeats in both sonatas.

The sound is clear enough. but without sufficient richness or color: the treble is particularly penetrating. Sine Qua Non's pressing is adequate. and Sherman's annotations make interesting reading.

H.G.

BEETHOVEN: Symphonies (9). Overtures: Egmont, Op. 84; Fidelio, Op. 72c; Leonore No. 3, Op 72b. Lucia Popp, soprano": Elena Obraztsova, mezzo"; Jon Vickers, tenor"; Martti Talvela, bass` : Cleveland Orchestra Chorus": Cleveland Orchestra, Lorin Maazel. cond. [Paul Myers. prod.] COLUMBIA M8X 35191, $47.98 (eight discs, manual sequence).

Symphonies: No. 1, in C. Op. 21; No 2, in 0, Op. 36; No 3, in E flat, Op 55(Eroica): No 4, in B flat, Op. 60; No 5. in C minor. Op. 67: No. 6. in F. Op. 68 (Pasroral): No. 7, in A. Op. 92; No. 8, in F, Op. 93: No. 9. in D minor. Op. 125.

--------

Explanation of symbols

Classical:

Budget

Historical

Reissue

Recorded tape:

Open Reel

8-Track Cartridge

Cassette

--------

The Cleveland Orchestra recorded its first Beethoven cycle in the late 1950s and early 1960s when George Szell's tenure as music director had brought it lo a well-deserved and long overdue prominence. The orchestra's second cycle may reflect the changes wrought by Szell's successor. Lorin Maazel, but for all the divergences demonstrates that this is a group with decided collective profile. The years of constant performance under such technicians as Artur Rodzinski, Erich Leinsdorf. Szell. and Maazel can hardly be overlooked in the formation of the crisply disciplined execution associated with the Cleveland brand name.

Szell favored a pronounced marcato articulation that gave his performances a spiky. astringent character. The almost obsessive emphasis on well-drilled attacks and releases combined with the traditional Germanic tempos and with such rhetorical devices of the older Central European school as Luftpousen frequently imparted an aura of ruthless pedantry to his interpretations. Maazel tends to be brisk rather than brusque, cool rather than cold. He has encouraged the orchestra to play with a somewhat more sensuous tone, and there are signs that its good discipline is less absolute than it used to be. Instances of the fractionally faltering unanimity that signals a conductor's less than complete control are few (I heard far more of them in the Maazel/Cleveland Beethoven cycle at Carnegie Hall several years ago), but in the main the orchestral work is more relaxed, less prickly than in the Szell performances-which brings gains as well as losses.

Maazel has a way of periodically inserting his mark into these outwardly objectivist readings. Like Szell he uses the occasional ritard. the minute adjustment--sometimes barely more than a tiny break-before a new section. but where Szell sounded dry and dogmatic. Maazel seems merely theatrical. Taken individually, almost all of Maazel’s touches can be justified intellectually, yet their ,aggregate effect can produce discomfort-such "insights" as the brasses' dynamic expansions in the last movement of Symphony No. 1 and at the end of the scherzo of No. 4. or the deliberately measured tempo for the choral return of the ode theme following the double fugue in the finale of No. 9. strike me as a mite fancy and self-conscious.

My enjoyment is also inhibited by the sound, which varies from work to. work but whose balances generally seem to me as much a product of electronic mixing as of a great orchestra's response to a highly proficient conductor. Although every strand is heard clearly, the perspective sounds uncomfortably constricted, as if the piccolo. contrabassoon, and fourth horn had been recorded on their own tracks and then inserted afterward. I missed a feeling of true solidity, particularly in No. 7.

One further peculiarity must be noted before proceeding to the individual performances. Maazel observes all repeats except in the scherzos of Nos. 7 and 9, which are both unaccountably shorn of even the minimal repeats heeded in most performances.

Fortunately, he does not include the spurious da capo repeat in the third movement of No. 1.

Symphony No. 1. briskly paced and rhythmically well sprung in all four movements, is in the tradition of Toscanini's NBC recording--a decided improvement over Szell's ably controlled but humorless account. No. 2 is one of the set's glories, a mercurial, perfectly controlled interpretation, close in manner to the recent Karajan and to the Szell. which was one of that sets triumphs.

The Eroica is well paced but lacks intensity. Part of the problem is the mushy sound; note the anemic-sounding timpani and the rather pale oboe and cellos in the Funeral March. (In fairness, the horns in the scherzo's trio are outstanding, and there is also good brass work in the fourth-movement coda.) No 4 is wonderfully played, though the constantly maintained tempos in the first two movements undercut such introspective moments as the ethereal dialogue between soft strings and timpani toward the end of the first-movement development. Jochum makes far more of that passage in his new recording (reviewed separately), and so did Toscanini in his NBC version-an interpretation in essentially the same briskly symmetrical mold as Maazel's.

No. 5 gets one of the set's best-sounding recordings, but the performance is inconsistent. veering between taut clarity and amorphousness. Those problematical "special" phrasings are most abundant here for example, the holdback before the fortissimo at first-movement bar 94 (Szell did this too, but more conservatively) and the affected phrasing forced on the solo oboe in its famous recitative. Moreover, there are problems with tempo relationships: The pia mosso ending of the Andante seems lethargic, and the fourth movement wavers between being massively imperious and jaunty and rushed.

Apart from some fussing in the "Thanksgiving" movement (the coda is particularly slow and sentimentalized) and an obtrusively exaggerated trumpet leadback at the end of the "Peasants' Merrymaking" trio, the Pastoral gets a ravishing performance--crystalline and beautifully graded in sound, patrician and well sprung in rhythm. There are no ritards from the bassoons and violins in those notorious fourths at first-movement bars 190 and 236, and the "Scene by the Brookside" flows beautifully.

No. 7 is mostly well paced. Maazel does vary the articulation (as in the fourth movement, where the violins are perfectly audible despite the very energetic tempo; the dotted figures beginning at bar 52 are also admirably weighted), but somehow the lack of a really solid sound causes the reading to seem slightly antiseptic. The Allegretto, which Szell took too briskly and nervously, begins to lapse into a somnolent dirgelike tread. No. 8, by welcome contrast, is splendidly curt and imposing. The first movement is rather broad, but the tremolos-caught in a forward, close perspective-impart a thrilling urgency. In the Allegretto, Maazel's metronome bears happy resemblance to Maazel's-both are suitably animated, a point of view aided by the orchestra's delicacy and cutting virtuosity.

The beautifully pointed third-movement trio and the caustic, witty finale put this performance up with the very best.

The opening movement of No. 9 is incisively paced-a good middle-of-the-road tempo, nicely controlled and steadily cumulative. The scherzo is beautifully lithe, although it is hurt by the omission of repeats and the timpani solo could he more robustly registered. The Adagio is luminous, phrased with a sinewy reserve that builds resolutely to the climax. In the finale. Maazel's sense of continuity-aside from that bit of deliberation following the orchestral double fugue-is absolutely knowing but perhaps a bit cut-and-dried.

Surely there could be more of a shattering sense of fulfillment when the ode theme blazes up in the full orchestra, and such moments as the timpani outburst preceding the entrance of the bass solo have been heard to more thrilling effect elsewhere.

The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus does resounding work in this recording, but my impression of the vocal quartet is of four superstars in slightly frayed condition, their vocal roughness magnified by close micro-phoning.

No.9, by the way, was simultaneously recorded by Telarc in a digital version, and we can expect the fruits of that labor in time (at a premium price, of course). The Columbia presentation is rounded out by crisp accounts of the three overtures (the Fidelio is particularly impressive) and comes in an attractive box. The booklet contains a Maazel essay on Beethoven that appeared originally in the New York Times and notes on the music by Phillip Ramey.

H.G.

----------------

Critic's Choice

The most noteworthy releases reviewed recently BACH: French Suites. Leonhardt. ABC/SEON AX 67036/2 (2). Inventions; Sinfonias. Leonhardt. ABC/SEON AX 67037. March.

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 6. Jochum. ANGEL S 37530, Apr.

BRAHMS: Songs. Ameling, Baldwin. PHILIPS 9500 398, March.

BRAHMS: String Quartets (3). Alban Berg Ot. TELEFUNKEN 26.35447 (2), Apr.

BRUCH: Violin Concertos Nos. 1, 2. Accardo, Masur. PHILIPS 9500 422, March.

Chopin: Etudes, Opp. 10, 25. Costa. SUPRAPHON 1 11 2188, May.

CHOPIN: Preludes, et al. Ashkenazy. LONDON CS 7101, Apr.

CLEMENTI: Symphonies (4). Scimone. ERATO STU 71174 (2), May.

DEBUSSY: Preludes, Book I. Michelangeli. DG 2531 200, March.

Dohnanyi: Chamber Works. HNH RECORDS 4072; HUNGAROTON SLPX 11624, 11853, March.

FRANCK: Symphony in D minor. Cantelli. RCA ARL 1-3005, March.

HANDEL: Alexander's Feast. Palmer, Johnson, Harnoncourt. TELEFUNKEN 26.35440(2), May.

MOZART: Vocal Works. Blegen, Zukerman. COLUMBIA M 35142, May.

RZEWSKI: The People United Will Never Be Defeated! Oppens. VANGUARD VSD 71248, Apr.

SAINT-SAENS: Violin/Orchestra Works. Hoelscher, Dervaux. SERAPHIM SIC 6111 (3), May.

SCHUBERT: Alfonso and Estrella. Mathis, Schreier, Suitner. ANGEL SCLX 3878 (3), May.

SCHUBERT: Symphonies (8), et al. Karajan. ANGEL SE 3862 (5), May.

SCHUBERT: Symphonies Nos. 4, 8. Giulini. DG 2531 047. Symphony No. 9. Jochum. QUINTES SENCE PMC 7100. Schippers. TURNABOUT QTV 34681. May.

STRAUSS, R.: Don Quixote; Don Juan. Haitink. PHILIPS 9500 440, Apr.

SWEELINCK: Harpsichord Works. Koopman. TELEFUNKEN 36.35360 (3), May.

Tchaikovsky: The Sleeping Beauty. Bonynge. LONDON CSA 2316 (3), May.

VERDI: La Battaglia di Legnano. Ricciarelli, Carreras, Gardelli. PHILIPS 6700 120 (2), Apr.

VIEUXTEMPS: Violin Concertos Nos. 4, 5. Perlman, Barenboim. ANGEL S 37484, May.

VIVALDI: Concertos, Op. 9 (La Cetra). Brown. ARGO 099D 3 (3), Apr.

ZELENKA: Orchestral Works. Camerata Bern. ARCHIV 2710 026 (3), March.

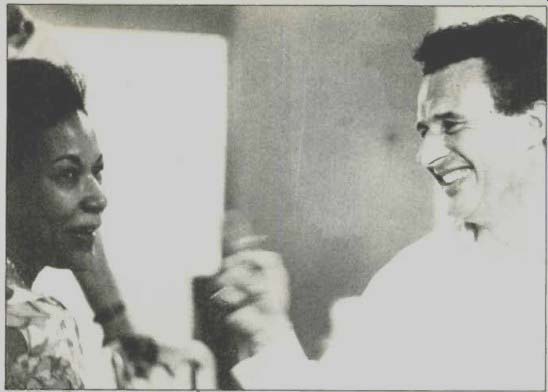

--------- Christiane Eda-Pierre and Colin Davis-a variable performance

of Béatrice et Bénédict

----------------

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 4, in B flat, Op. 60; Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72b. London Symphony Orchestra, Eugen Jochum, cond. [John Willan, prod.] ANGEL S 37529, $7.98 (SO-encoded disc). Tape: 4XS 37529, $7.98.

Jochum's new Fourth is similar in style to his last one, with the Concertgebouw for Philips. Again one finds a wealth of geniality, expressed in-for me-slightly laggard tempos and overripe sonorities, but as before the playing has obvious devotion and structured intelligence behind it. And in fairness, Jochum's finale, deliberately paced though it is, has much more of the requisite lightness than some others I can think of--Szell's or Klemperer's--that feature similar tempos.

Leonore No. 3 is forthright in interpretation, though here there are surprising instances of imprecise orchestral playing and rhythmically slipshod (or is it Furtwanglerian?) phrasing. Angel's sound is as impressive as in Jochum's Beethoven Fifth (S 37463, August 1978) and Sixth (S 37530, April 1979)-note the clarity of the timpani's quiet taps.

H.G.

BERLIOZ: Béatrice et Benedict.

Hero Chnshane Eda-Pierre (s)

Beatrice Janet Baker (ms)

Ursule Helen Watts (a)

Benedict Robert Tear (1)

Claudio Thomas Allen (b)

Somarone Jules Bastin (bs)

Don Pedro Robert Lloyd (bs)

Leonato Richard Van Allan (spkr)

John Alldis Choir, London Symphony Orchestra, Colin Davis, cond. PHILIPS 6700 121, $17.96 (two discs, manual sequence).

Comparison: Veasey, Mitchinson, Davis Ois. SOL 256/7 Set to his own libretto after Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing, Berlioz' last major work is an opero-comique--that is, an opera with spoken dialogue. In Colin Davis' 1962 Oiseau-Lyre recording, the dialogue was omitted entirely: the two numbers involving the pedantic musician Somarone (an invention of Berlioz, not found in Shakespeare), which in their full form don't make sense without the dialogue, were abbreviated, and the elaborate cadenza for Héro's aria was cut in half. The new Philips recording incorporates a modicum of spoken dialogue and also restores these musical omissions-a gain not only for completeness, but also for sense: The two opening choral numbers, which use the same musical material, are in different keys (B flat and A. respectively) and were clearly not meant to be played in immediate succession; they benefit from the intervening air space generated by the dialogue.

Predictably, some of the singers don't speak the dialogue very well. Helen Watts is particularly, if only briefly, unconvincing, and I'm mystified why Richard Van Allan's something less than idiomatic delivery should have been tolerated in a role involving no singing, merely the ability to speak French well. It could be worse, though-there are two native speakers, Jules Bastin and Christiane Eda-Pierre, and two leads who speak the language idiomatically, Janet Baker and Robert Tear.

The trouble is, those two leads don't sing very well, and that is more important. Tear is in such trouble above the staff as to be downright unlistenable, and every phrase that involves higher notes has clearly been shaped more by desperation Than by musical considerations. (He's not very happy at the lower end of the part, either, but that is at least less conspicuous.) Baker sings, as usual, with spirit, but her current vocal condition is severely limiting, the unsteady tone a serious liability in slower music.

Eda-Pierre isn't a model of firmness either, though her flexibility is welcome in the aster part of Héro's aria. And with Watts, á the only holdover from the Oiseau-Lyre cast, in appreciably older voice, the trio of the three ladies is a trial of warring wobbles. Indeed, the only unalloyed vocal pleasure afforded by this set is Bastin's solid, humorous, idiomatic Somarone.

When I first listened to the Philips set, the music seemed rather less buoyant and inventive than I remembered. Alarmed, I put on the Oiseau-Lyre set; lo and behold, wit and sentiment flowed as in years past. It took some time to pin down the reasons for this discrepancy (not unlike, I have since learned, the experience reported this month by Conrad L. Osborne vis-á-vis London's new recording of Pogliacci)-and it wasn't simply a result of the unsatisfactory singing in the new set, although the temptation to blare that was naturally very great.

Some close comparisons disclosed that, for all the greater overall smoothness and solidity of the Philips sound, there is less detail audible at times-and, since this is an opera by Berlioz, much wit and sentiment is made individual and vivid by orchestral detail. Not that the detail is actually inaudible (although I cannot in fact hear the dotted rhythm in the strings at "tin pared Bonheur/Est-il pour mon Coeur" in Bénédict's aria), but it isn't placed as forwardly, doesn't come to the attention as readily as in the older set. In effect, after listening to a number in the old recording, the new one became more enjoyable because now I know "what to listen for." Other things, not major in themselves, also contribute to the eventually significant difference in overall effect. The earlier cast is generally sharper rhythmically, quicker off the mark-especially April Cantelo as against Eda-Pierre. And just as the Oiseau-Lyre trio of women blends better. so the men John Cameron and John Shirley-Quirk are better matched than Thomas Allen and Robert Lloyd. The famous Nocturne, at the end of Act I, went with a gentle swing in 1962 that Davis has not quite recaptured now.

If you don't know the opera, by all means start with the Oiseau-Lyre set; though its omissions undoubtedly misrepresent the letter of the work, the musical performance is truer to the spirit. Those who already own the earlier set may wish to investigate the new one; they will find, in addition to the discs, an expectably fine essay and translation of the libretto by David Cairns.

D.H.

BRAHMS: Organ Works. Jan Hora, organ of St. Naurice's Cathedral, Olomouc (Czechoslovakia). [Pavel Kühn, prod.] SUPRAPHON 1948, $8.98.

Fugue in A flat minor. Chorale Prelude and Fugue. "O Traurgkeit." Chorale Preludes (11), Op. 122.

Brahms left rather little music for organ-he composed some early preludes and fugues and in his last year completed the eleven Chorale Preludes, Op. 122-but in the best of these pieces he confided some of his deepest and most intensely personal feelings. Jan Hora. plays these richly emotive works in a deadpan. metronomic manner.

Never does the slightest rhythmic inflection disturb the note-spinning: never does one get a sense of phrase, of melodic shape, of harmonic tension. A pianist would be laughed off the stage for this sort of playing, and. without the piano's range of varied touch, its effect on the organ is unbearable.

To make matters worse. Hora's instrument (the builder of which is unidentified) has a mean and mincing tone. and the excessive proximity of the microphones negates whatever acoustical warmth may exist in its setting.S.C.

CHERUBINI: Medea (ed. Lachner).

Medea

Glauce

Maids Veronika Kincses(s), Katal Nens Giasone Creonte Sylvia Sass (s)

Magda Kalmar (s)

n Szokelalvy-Nagy (ms)

Klara Takacs (ms)

Verano Luchetu (t)

Kolos Kovacs (bs)

Hungarian Radio and Television Chorus, Budapest Symphony Orchestra, Lamberto Gardelli, cond. [László Beck, prod.] HUNGAROTON SLPX 11904/6, $23.94 (three discs, manual sequence). Comparisons.

Callas. Penno, Bernstein/La Scala Turn. THS 65157/9

Jones, Prevedi, Gardelli/Sta. Cecilia Lon. OSA 1389

The persistence of Cherubini's marmoreal, not to say glacial, tragedy is to me inexplicable, except in terms of the opportunities it offers the dramatic soprano to show her mettle by giving vent at length to a number of strong emotions: jealousy, rage, vindictiveness, motherly love that alternates with murderousness. Medea, in the immortal words of Bottom, is a part to tear a cat in, It is a part that has proved highly tempting to prima donnas who fancy themselves as singing actresses, ever since Maria Callas took it up at the 1953 Florence May Festival and at a blow restored the long-neglected opera to international currency-at least for a while.

Yet as this new recording once again demonstrates. Medea offers no surefire guarantee of success. The fact that Callas enjoyed a series of triumphs in it is somewhat deceptive. The overwhelming sense of inevitable tragedy she evoked whenever she sang the role owed, it now seems clear, rather more to her interpretive genius than to Cherubini's creative skills. (Furthermore, a far from negligible part of her vivid characterization was established in the orchestrally, accompanied recitatives composed by Franz Lachner in the mid-nineteenth century in place of what was originally a mixture of spoken dialogue, mélodrame, and string-accompanied recitative.) In the hands of lesser interpretive talents. the opera-monumental in conception, classically decorous (all the bloody deeds on which the tragedy turns take place off-stage), its narrative stiffened by a plenitude of symphonic orchestral passages--remains well-meaning fustian, a would-be great occasion lacking the necessary animating spark.

Or so the lack of artistic success attendant upon those who have followed in the wake of Callas would suggest, whether Eileen Farrell on the concert platform. Leonie Rysanek on-stage. or Gwyneth Jones on records. Now Sylvia Sass can be added to their number. Sass is a striking-looking young woman who. though still under 30, has already achieved in her native Hungary, in France, and in Britain a réclame with the public and the press that, having heard her weakly sung Traviata at Aix-en-Provence and her immature ' Pasco at the Met, I find astonishing.

---- Krystian Zimerman Chopin worth investigating.

Here she is no less out of her depth. both vocally and interpretively. For one thing, she is monotonous. From her entrance on the scene to the opera's final curtain. Sass maintains a single note of emotional outrage. The dissimulation Medea practices on Creonte to win her another day in Corinth, her deception of Giasone by means of which she gains his assent to her temporary repossession of their sons. the conflict she experiences between maternal tenderness and the impulse to revenge herself on Giasone through the children's murder--all these elude completely the soprano's very limited interpretive grasp. Nowhere does she respond to the varying needs of the drama. nowhere does she follow the psychological course of Medea's machinations.

Sass's chance of success is in any case hound to be hampered by her vocal inadequacies. Lacking both dramatic bite and an assured lower register, she simply cannot project Medea's commanding personality.

In the Act II Giasone/Medea duet, for example, the latter's threatening and hate-filled asides make hardly any impression because Sass does not know how to give such utterances the right kind of weight, emphasis, and variety.

In terms of characterization. Veriano Luchetti's Giasone is no less monochromatic. In addition, his tendency to heave himself up' into notes above the staff quickly becomes annoying. But Luchetti, unlike his colleagues, at least gives one a certain amount of pleasure through his Italian enunciation. Magda Kalm;ír. the Glauce. has her points. though she has an obtrusively weak lower register and is troubled by the high Cs in her aria.

The chorus and orchestra are satisfactory. Lamberto Gardelli is sound but un-exciting. The opera includes the Lachner Iecitatives and is heard in the standard Zaugarini, translation of the original French. Like the current London recording, also conducted by Gardelfi, Hungarotori s Medea uses the Ricordi edition, but with minor cuts at the end of Act I, in the Ciasone/Medea duet, in the Act II concertato, and in the Act III finale, The London set offers a better Neris (Fiorenza Cossotto) and minimally livelier conducting but is hardly much of an improvement. Bruno Prevedi (Giasone) has perpetual recourse to intrusive aspirates; Pilar Lorengar (Glauce) is in her most fluttery voice and is routed by the technical demands of her aira: and Cwyneth Jones (Medea) is hopelessly beyond her depth.

For those who do not mind off-the-air mono sound, the clear choice is Turnabout's issue of Callas' 1953 La Scala performance. Leonard Bernstein's conducting is irresistibly impetuous, while Callas, in superb if reckless voice, is at her most thrilling and illuminating: To hear her agonized vacillation over her sons is to see immediately how a great artist can transfigure essentially frigid music. Her commercial recording (Ricordi/Mercury. currently unavailable). made four years later under Tullio Serafin. finds her sounding tired and Serafin under-energized.

Turnabout supplies an uncommunicative leaflet. London an Italian-English libretto plus notes, and Hungaroton a libretto in Italian. English. Hungarian, German, and Russian plus good, if occasionally quaintly phrased. notes. Hungaroton's recording is less impressive than London's, for all that the latter is more than ten years old. In the new set, the singers are too closely miked, and the big concerted scenes lack a sense of space adequate to the number of participants.

D.S.H.

CHOPIN: Waltzes (14). Krystian Zimerman, piano. [Cord Garber and Hanno Rinke, prod.]

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 965, $8.98.

Tape: 3300 965, $8.98.

Waltzes: in E flat, Op. 18. in A flat, Op. 34, No. 1; in A minor, Op. 34, No. 2; in F, Op. 34, No. 3; in A flat, Op. 42; in D flat, Op. 64, No. 1 (Minute): in C sharp minor, Op. 64, No. 2; in A flat, Op. 64, No. 3; in A flat, Op. 69, No. 1; in B minor, Op. 69, No. 2; in G flat, Op. 70, No. 1; in F minor, Op. 70, No. 2; m D flat, Op. 70, No. 3; in E minor, Op. posth.

Zimerman plays only the standard fourteen waltzes. which puts his disc al a competitive disadvantage with those versions that contain as many as five extra pieces. Nor. to be frank. do I find his playing as satisfying here as in his earlier recordings of Chopin (DG 2530 826. October 1977) and Mozart (2531 052, January 1979). He begins unpromisingly: The E flat major Valse brilliante, Op. 18. is tonally hard-edged. overzealously articulated. and ridden with finicky tempo adjustments. This technically superb but charmless pianism-in works that are nine-tenths courtly charm even when deeper emotions are present--continues throughout the first side and recurs occasionally on the second. as in the final E minor Waltz. Op. posth.

In fairness, some of Zimerman's playing is breathtakingly nuanced and beautifully sinuous, particularly as he relaxes into a more communicative state. The A flat Waltz of Op. 64 has an elastic, undulating line above the finest-spun bass line imaginable, and all the pieces of Opp. 69 and 70 bloom with prismatic transparency and seductive half-tints.

Textually, Zimerman goes his own way.

He uses the Paderewski Polish text for most of the waltzes but plays the Fontana versions of the Iwo Op. 69 pieces-and in the B minor, Op. 69. No. 2, switches to the Oxford University Press version's unexpectedly pungent variant of the last four measures.

The disc is only a partial success. but it merits investigation.

H.G.

HAYDN: Die Schbpfung.

Gabriel. Eva Helen Donath (s)

Unel Robert Tear (t)

Raphael. Adam Jose van Dam (bs-b)

Leslie Pearson, harpsichord; Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra, Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos, cond. [Christopher Bishop, prod.]

ANGEL SB 3859, $15.98 (two SO-encoded discs, automatic sequence). HAYDN: Die Schopfung.

Gabriel Lucia Popp (s)

Eva Helena Dose (s)

Unel Werner Hollweg (I)

Adam Benjamin Luzon (b)

Raphael Kurt Moll (bs)

Brighton Festival Chorus, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Antal Dorati, harpsichord and cond. [James Mallinson, prod.]

LONDON OSA 12108, $17.96 (two discs, automatic sequence). Tape: +' OSA5 12108, $17.96.

HAYDN: Die Jahreszeiten.

Hanne Ileana Cotrubas (s)

Lukas Werner Krenn (I)

Simon Hans Sotin (bs)

Roger Vignoles, harpsichord; Brighton Festival Chrous, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Antal Dorati, cond. [James Mallinson, prod.]

LONDON OSA 13128, $26.94 (three discs, automatic sequence). Tape: OSA5 13128, $26.94.

Antal Dorati has done more to revitalize the music of Haydn, and to reacquaint audiences with that composer's works, than any other conductor of our era. His Haydn discs till up the shelves and keep coming.

They can be counted on to be well performed and well thought out--they are, pardon the pun. as reliable as the seasons.

That said, I prefer The Creation as overseen by Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos. Dorati's does have the imprimatur of H. C. Robbins Landon's scholarly notes and the luxury of separate soloists for Adam and Eva. but Fruhbeck's performance has an aura of spontaneity and delight that Dorati seems to have lost. The EMI/Angel engineers haven't put the soloists as far up front as Decca/London's. and if this and some other decisions end up causing a few minor problems in the Frühbeck set. at least this Creation doesn't sound as premeditated and routine as Dorati's.

There are more similarities in these two versions of the composer's first great oratorio than there are differences. Both recordings were made in England. and despite the characteristic divergences in the recorded sound. there is not much to choose between the Philharmonia Orchestra and the Royal Philharmonic: both are adequate to the job at hand. The two conductors' tempos are essentially the same. though Fruhbeck allows himself to go both slower and faster than Dorati. who opts for moderation at every corner. Similarly, he incorporates more sonic outbursts than Dorati, and, though these blazes may annoy the purists, Haydn would probably have greeted them with cheers.

--- Antal Dorati Continuing the Haydn revival

Once Dorati has set up these conservative parameters, it is surprising and even off-pulling to hear him create tension by letting the orchestra pull against the soloists in several of the more active and florid passages. Where instruments and voice or voices should mesh elegantly. Dorati sets them at odds, evidently purposely.

The results make me uncomfortable.

I can't imagine that anyone would choose one or the other of these recordings because it does or doesn't double the soprano and bass roles. Haydn himself could settle for only three soloists. but among recent recordings the trend has been to five. (Karajan. in fact. used six: Werner Krenn was brought in to complete the role of Uriel after Fritz Wunderlich's death.) Although my favorite recording. the earlier London set conducted by Karl Münchinger (OSA 1271. just deleted). uses five soloists, what matters is not number but effectiveness. and Dorati seems to defeat his own case when he brings in Helena Dúse as Eva instead of letting Lucia Popp double the soprano roles. As Gabriel. Popp is little short of wondrous-light. clear. pure, and limpid.

Helen Donath (Angel) is only slightly less impressive: her technique is on a par with Popp's but the timbre is not as pleasing.

Obviously there are gains from having a bass sing Raphael and bringing in a baritone for Adam. London's Kurt Moll is a first-rate Raphael, but so, except in the lowest passages. is Angel's lose'. an Dam, and I will put up with Van Dam's struggles on the bottom in order to hear his Adam, which is rich. smooth, and attractively passionate.

Between the tenors. there is little choice: Werner Hollweg's tones are edgy, while Robert Tear's lines are cool and stylish, more attuned to my idea of what archangels sound like.

Dorati plays his own harpsichord continuo in his Creation (in the name of authenticity one would have expected London to put the continuo closer to the aural front) but not in his recording of The Seasons. made in 1977. a year later. The congenial later oratorio is less demanding and therefore easier to put across than The Creation. Dorati's interpretation is full of lilt and dances: if there are long passages on these three discs that are less than fascinating. the fault may he more Haydn's than the performers'. Ileana Cotrubas is a lovely Hanne in this recording, which is the equal of the best of those still available. Indeed. the juxtaposition of Donath. Popp, and Cotrubas in these three sets is enough to make one rejoice in the current abundance of graceful. flexible soprano voices. The two men, Krenn (Lukas) and Bans Sot in (Simon). are no less congenial. and in The Seasons the Brighton Festival Chorus sings with more gumption and spark than in The Creation.

K.M.

LEONCAVALLO: I Pagliacci. For a feature article, see page 66.

MASCAGNI: Cavalleria rusticana. For a feature article, see page 66.

Massenet: Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame.

Angels Jean A Poet Monk A Painter Monk A Musican Monk Brother Bonitace The Prior A Sculptor Monk Antoinette Rossi (s), Amanda Cassini (ms)

Alain Vanzo (t)

Tibére Rattalli (I)

Jean-Marie Frémeau (b)

Michel Carey (b)

Jules Bastin (bs)

Marc Vento (bs)

Jean-Jacques Douméne (bs)

Monte Carlo Opera Chorus and Orchestra, Roger Boutry, cond. [Gréco Casadesus, prod.]

ANGEL SBLX 3877, $16.98 (two discs, automatic sequence). Even in the years when Massenet was known principally by Nanon and Werther, his short (approximately ninety minutes) three-act "miracle" opera Le Jongleur de Notre-Dome enjoyed a general critical reputation as one of the best of his other operas. But performances have always been rare. owing to a variety of factors: the all-male cast, the gentler music-making that Massenet employs, and perhaps also the sanctimonious nature of the score itself.

The opera was written because Massenet became interested in a libretto sent to him, based on a story by Anatole France. Even though he was at the time a famous composer. he could not find a home for the finished work until the impresario of the Monte Carlo Opera. Raoul Gunsbowg, accepted and produced it February 11, 1902.

beginning Massenet's relationship with that opera house, which continued after his death. After its Monte Carlo premiere, the opera was given at the Opéra-Comique, butt it is fair to say that its international renown was largely occasioned by the fact that Mary Garden saw it as a vehicle for her talents and transformed the title role to a trayesti part for Oscar Hammerstein's Manhattan Opera Company November 27, 1908.

The story is a simple one, familiar because its clearest imitator has now become the more performed work: Puccini's Suor Angelico. (The story also has points of reference with Menotti's Amuhl and the Night Visitors.) In the fourteenth century a poor, half-starved itinerant jongleur (the word is untranslatable, including in it elements of an acrobat, musician, minstrel, juggler, and magician), simple and pure in heart, is accepted as a novice in the Abbey of Cluny.

He is awed by the sophistication and expertise of the monks, who look upon him with overt condescension-all but the kindly monk/cook Boniface. The monks celebrate the Virgin by pride-fully putting forth their specialties-painting, sculpture, music-so that lean, the jongleur, is left utterly confused as to how to compete with them. He does so in the only way he knows, by going clandestinely to her statue and performing his pitiful but heartfelt act. The monks, eavesdropping, are scandalized by the sacrilege-all but Boniface-but are awestruck when the statue comes to life and wipes his sweated face with her robe.

Maurice Léna's libretto is excellent in its concise elaboration of France's story and in its delineation of character (particularly that of Boniface), but in the accepted nineteenth-century manner he changed the ending so that the Virgin merely blesses jean, while surrounded by holy light. Celestial voices are heard, and jean expires in bliss.

It is not surprising that these pages, in Massenet's well-worked "creeping Jesus" style, are the weakest in the score, only partly redeemed by the nobly understated final page.

Yet the overall innocence permeating the story, expressed in the final page in the Prior's words, "Blessed are the simple, for they shall see God"--the music of which heads the score and acts as a loosely applied ground bass at various points--is beautifully set forward in Massenet's writing. His craftsmanship is everywhere in evidence: the expressivity of his instrumentation, the use of archaic modal echoes, the directness and uniformity of the music.

Boniface's "Legend of the Sage Plant" ranks with Massenet's finest inspirations, as does the 9/8 theme that represents the contemplative repose of the monastery.

Even given its "miracle" music, Le Jongleur stands as one of Massenet's most consistent and persuasive scores.

This premiere recording uses the original tenor setting; the soprano recension was never explicitly sanctioned by Massenet, although he well realized the value of Garden's contributions--not least to his bank account. A soprano voice would provide an appropriate element of naive simplicity, but Alain Vanzo's fluid and forthright tenor voice makes a poignant lean, particularly in his big scene before the Virgin. Vanzo must use all his art to suggest a youthful naiveté he no longer inherently commands, and now and then I would like more soft shading than he provides.

The rest of the cast is solid without being outstanding: lutes Bastin draws a good deal, but not all, from the role of Bonifacecrucial parts of the "Legend of the Sage Plant" song lie in a weak area of his voice.

Roger Boutry leads a strong performance from his ensemble and is rewarded by expressive playing, especially from Michel Pons on the solo viola d'amore.

The recording benefits from a welcome naturalness in the blend of voices. chorus, and orchestra, with a few quite appropriate "stage effect" sounds: would that more of today's opera recordings were engineered in this low-key way. In sum, a fine job of an opera worthy of attention.

P.J.S.

MILHAUD: Protée: Suite Symphonique No. 2. Les Songes. Utah Symphony Orchestra and Utah Chamber Orchestra', Maurice Abravanel, cond. [George Sponhaltz, prod.]

ANGEL S 37317, $7.98. Tape: 9 4XS 37317, $7.98.

Most music lovers had buried Darius Milhaud long before his death on June 22, 1974.

Although he continued to compose prolifically throughout his later years, he had already passed into history, remembered almost entirely by his earlier works. My current copy of SCHWANN 1, for example, lists nothing later than a single work from the mid-Fifties, several from the Forties, but mostly those-the best known and most often recorded--from the Thirties and earlier. And so it's surprising to encounter two more all but forgotten works from that early period. They show us a Milhaud who is an even more impudently imaginative spokesman for his age than we have usually credited. These scores retain. more than a half-century later, un-faded piquancy and forcefulness.

The last of Milhaud's several re-workings of incidental music for Claudel's play Protée was responsible for one of the greatest twentieth-century Parisian concert scandals. Its premiere, conducted by Pierné at the Colonne Concerts on October 24, 1920, caused a near riot (the gendarmes had to be called in!) that outdid even the stormy reception of Stravinsky's Sacre some seven years earlier. And no wonder, for if ever a composer bawdily nose-thumbed the musical establishment, it was Milhaud in this suite. It seems not to have been recorded since Monteux's Victor 78s of 1946 (except for a noncommercial Steinberg/Pittsburgh Symphony LP of the early Fifties), and since the score is rarely if ever revived in American concert halls, today's listeners are likely to be unprepared for its bite, impact, and exuberance.

The os.erside ballet score Les Songes, for reduced (theater-pit) orchestra. has had scant success on the stage despite its Balanchine choreography originally starring Toumanova. It hasn't fared any better on records; I know of only the composer's mid-Thirties Columbia version with the Paris Symphony. But Abravanel, who conducted the 1933 Paris stage premiere, obviously has never lost faith in this episodic, diversified work, notable for its rowdily festive moments and for its inexhaustibly inventive orchestral scoring.

Without even a suggestion of camping-up, Abravanel and his players, who manage to sound more French than Utahan, succeed in restoring all the vitality and uninhibited spirit of the Twenties and early Thirties, and their invigorating playing is brilliantly reproduced by engineer Robert Norberg.

R.Q.D.

MOZART: Concertos for Oboe and Orchestra: in C, K. 314; in E flat, K. Anh. 294b (attrib.). Han de Vries, oboe; Prague Chamber Orchestra, Anton Kersjes, cond. [Eduard Herzog, prod.]

ANGEL S 37534, $7.98 (SO-encoded disc).

The distinguished Dutch oboist Han de Vries, who for seven years was a Concertgebouw principal, deserves better support than he is given in this EMI/Supraphon coproduction. Nothing can conceal his impeccable musical artistry or his subtle tone coloring, more slender-toned but no-less elegant or individual than that of most noted oboe soloists. But the overenthusiastic Anton Kersjes drives the Prague Chamber Orchestra far too hard, and the recording captures only too candidly its penetrating high frequencies and its generally overloud, overemphatic dynamics. Or is it possible that some of the fault should be ascribed to the American disc processing? Unfortunately, then, I can commend this disc only to oboe connoisseurs who don't want to miss knowing De Vries better. For Mozarteans, it is no real competition for either the Holliger or the Black version of K. 314 (Philips 6500 174 and 6500 379, respectively). The inclusion of the E flat Concerto, K. Anh. 294b, is a dubious advantage, since this largely reconstructed work is patently spurious--indeed, not even remotely "Mozartean." However, it is pleasant enough music by some competent late-eighteenth-century composer, with a disarming slow-movement melody. And there is no other available recording.

R.D.D.

MUSSORGSKY: Pictures at an Exhibition (arr. Howarth). Philip Jones Brass Ensemble, Elgar Howarth, cond. [Chris Hazell, prod.] ARGO ZRG 885, $8.98. Tape: KZRC 885, $8.98.

For so staunch a wind-music advocate as I've long been, as well as for so consistent an admirer of the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble's superb earlier recordings, it's awkward to have to brand the daring present project as essentially a failure. The principal fault is Howarth the conductor, not Howarth the transcriber. Perhaps some of the executant demands are too much for even these British virtuosos to manage at top speed, or perhaps they haven't been given enough rehearsal time to avoid seeming to sight-read their parts, but most likely the conductor's reading is simply routinely--even sluggishly--dull.

Howarth's transcription itself is as idiomatic as possible, and certainly marvelously ingenious, but it is handicapped by the constant predicament of either imitating the Ravel orchestration's brass scoring or deliberately attempting something different and almost invariably less suitable. What remains, then, are some magnificent brass sonorities magnificently re-corded--which well may be enough for brass aficionados but never add up to a satisfying Pictures.

R.D.D.

RAVEL: Vocal and Instrumental Works. Various performers. [Marc J. Aubort and Joanna Nickrenz, prod.] NONESUCH H 71355, $4.96.

Chanson madécasses (Jan DeGaetani, mezzo-soprano: Paul Dunkel, flute; Donald Anderson, cello; Gilbert Kalish, piano). Les Sites auriculaires; Frontispicer (Paul Jacobs, Kalish, and Teresa Sterner, pianos). Sonata for Violin and Cello (Isidore Cohen, Timothy Eddy).

Nonesuch offers an irresistible bargain sampling of what might be called the uncharacteristic Ravel. The 1895 two-piano Sites ouriculoires includes the keyboard original of the "Hahanera" from the Hopsodie espagnole and a rollicking piece called "Entre cloches." The 1919 Frontispice for piano five hands--whose fifteen bars are printed at the beginning of a collection of Ricciotto Canudo's poetry--is suffused with polyrhythm and polytonality.

The 1922 sonata for violin and cello, the only such work to gain any kind of toehold in the repertory. is treasured for its blunt rhythmic patterns, stabbing dissonances, and sections of swaying indolence. The 1925-26 Chansons madécasses are set to eighteenth-century poems of Evariste-Désiré de Parny, which for a while masqueraded as ethnically authentic. Eroticism and assertive racial consciousness are compactly juxtaposed in the text, and Ravel's setting of it uses the solo voice (a baritone or mezzo) and an ensemble of flute, piano, and cello with uncanny acumen, evocativeness, and economy.

All the music is presented with impeccable taste and skill. Gilbert Kalish and Paul jacobs, two of the better pianists around for such repertoire, collaborate effectively in the Sites, though their "Habanera" could be accused of excess deliberation. (Nonesuch's impresario Tracey Sterne provides the fifth hand in the Frontispiece.) The piano pieces sound forth with impressive dynamic range and bass.

The suppleness and remoteness with which Ian DeGaetani sings the Chansons are hypnotic, and many a rival recording is lacking such neat coordination between singer and instrumental trio. In the violin-cello sonata, Isidore Cohen collaborates with Timothy Eddy as smoothly as if the latter were his regular Beaux Arts Trio cello partner, Bernard Greenhouse.

For those who want to explore this music more systematically, the catalogs offer the usual complicating choices. The piano-duet miniatures appear in the Kontarsky brothers' two-disc Debussy/Ravel set (DG 2707-072), which contains the two-piano original of the entire Hapsodie espagnole. The piano pieces also appear, played by Queens College faculty members without quite the muted translucency of the Nonesuch performance, on a Musical Heritage Society disc (MHS 3581) that is indispensable for a number of Ravel rarities, including the only recording thus far of the lovely posthumous violin-and-piano sonata movement.

The alternatives for the Chansons go in both directions emotionally from DeGaetani's performance: Fischer-Dieskau's virtuosically accompanied interpretation (HNH Records 4(45, with Fauré's Bonne chanson and Poulenc's Bol masque) is larger than life: Janet Baker's (Oiseau-Lyre SOL 298, with Ravel's Trois poémes de Mallurmé and songs by Chausson and Delage) is more meltingly tender. The Columbia recording of the violin-cello sonata by Jaime Laredo and Leslie Parnas (M 33529) is more incisive than that of Cohen and Eddy, with more lucid stereo separation. and it is paired with the finest performance of Ravel's piano trio in my experience.

A.C.

STRAUSS, R.: Ariadne auf Naxos, Op. 60. The Prima Donna: Anadne Zerbineda Najade Echo The Composer Dryade The Tenor: Bacchus The Dance Master Scaramuccio Brighella An Officer The Music Master Harlekin Truttaldin A Wigmaker A Lackey The Major-Domo Leontyne Price (s)

Edita Gruberova (s)

Deborah Cook (s)

Norma Bunowes (s)

Tatiana Troyanos (ms)

End Hartle (ms)

René Kollo (t)

Heinz Zednik (t)

Kurt Equiluz (t)

Gerhard Unger (t)

Peter Weber (t)

Walter Berry(b)

Barry McDaniel (b)

Manfred Jungwirth (bs)

Georg Tichy(bs)

Alfred Sramek (bs)

Erich Kunz (spkr)

London Philharmonic Orchestra, Georg Solti, cond. [Christopher Raeburn, prod.]

LONDON OSAD 13131, $26.94 (three discs, automatic sequence).

Comparisons: Karajan/Philharmonia Ang. CL 3532 Leinsdort/ Vienna Phil. Lon. OSA 13100

Historically, the second version of the Strauss-Hofmannsthal Ariadne oaf Naxos has been remarkably well performed on records. Writing in these pages in February 1989, Conrad L Osborne hypothesized.

"Perhaps it is the special quality of this opera (and its special difficulty) that has saved it on records: the cast requirements are so severe and unusual and the orchestral demands so high (in terms of quality. of course. not quantity) that one would not dream of undertaking the piece without an extraordinary assemblage of talent." Not long thereafter. however, came Bohm's stereo version, seriously under-cast as far as the opera seria principals were concerned.

Now here is the next Ariadne, and the jinx is still on. if in different ways.

The major problem, I feel, is that Sir Georg Solti misses the point a good deal of the time. At the start of the opera proper, the G major trio of nymphs has no spine, no tonal continuity: I found myself turning up the volume trying to hear what was missing "between the notes." but without success.

This isn't really a matter of vocal inadequacy: though the lowest voice of the trio is uncertain. the sopranos are firm enough. Essentially, by voices and instruments, the music is pecked at: impressionistic petit point instead of elegant tapestry.

Ariadne's big solo veers from slow motion to virtually no motion at all. the conductor making enormous ritards to underline even the most local cadential events as if they were major articulations. And the final duet undergoes the same sort of debilitating distensions-occasionally in aid of the singers. but as often clearly a matter of the conductor's choice. The bufo material, on the other hand, though taken at a respectably bouncy clip is so uniformly and unvaryingly stressed as to lose both shape and significant direction: Everything seems to be one-heat-to-the-bar. As a result, nothing much ever seems to be happening musically.

To these reservations must be added the qualification that the LPO's playing, though certainly competent and clearly recorded, is hardly up to the level of some other recorded ensembles in this opera: Karajan's Philharmonia (don't miss Dennis Brain's horn playing in "Ein schones war"), the Vienna Philharmonic (whether for Bohm in 1944 or Leinsdorf in 1959). Kempe's Dresden State Orchestra. (On this honor roll certainly belongs the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra as it played this work during the recent season-will there ever he a commercial recording of its present superb estate?) Once upon a time. Leontyne Price might have done justice to the requirements of Ariadne's music. Occasionally. a phrase still surges out with the familiar temperament and something like the old warmth and richness of tone. A certain rapt intensity is also germane-in the duet with Bacchus, at "Ich weirs, so ist es (tort wohin du mich führest," for example. Most of the time, the tone is dry. wooden, and the German diction insufficiently specific to give the character profile. Neither vocally nor interpretively can Price's work be coin-pared to Schwarzkopf's magisterial performance (in the Karajan set), or to the now unavailable performances of Reining (Bohm, 1944) or janowitz (Kempe). René Kollo may he a rather plain Bacchus: he does manage to get through this murderous part without coming to conspicuous grief, though the notes around the break are not really comfortable. and his soft singing in the upper register is chancy.

We have heard worse performances of this role: )an Peerce (Leinsdorf) makes a more musical effect, and the now deleted BASF resurrection of a 1935 German broadcast (the-opera only, without the Prologue) preserved the genuinely heroic singing of Helge Roswaenge.

In Zerhinetta's coloratura intricacies, Edita Gruberová's accurate singing is hard to fault, though the legato lines of the Prologue duet show up a beat in the lower range. This is a brittle comedienne. with a squeezed. Slavic tone and a small but distinct Slavic accent-far less winning than Erna Berger (in the BASF set) or Rita Streich (Karajan). Her companions are led by Barry McDaniel (also the Harlekin of Bcihm's stereo version), a warm, slightly wobbly voice: they are more efficient than characterful.

In the Prologue. we encounter two old friends: Tatiana Troyanos as the Compose-, familiar from the second Btihm recording. and Walter Berry as the Music Master (which he sang earlier for Leinsdorf, also doubling then as Harlekin). Troyanos is a fine singer and a committed interpreter, who deserves her success in the part onstage. Still, for all her strength in the lower reaches of the part. crucial moments clearly demand a voice that opens up as it climbs toward B flat, and in this she is no match for Irmgard Seefried (Bóhm, 1944, and Karajan a decade later) or Sena jurinac (Leinsdorf). Berry's voice is simply no longer at ease in this music: he substitutes exaggerated inflections for his former easy, secure pitching. Erich Kunz-Bohm's Harlekin in 1944is now a flavorful Major-Domo (much preferable, in particular, to the low-comedy undertones that intrude on Kurt Preger's work for Leinsdorf). Otherwise in the Prologue.

Peter Weber's strenuous but unfunny Officer and Alfred Srarnek's overstressed Lackey attract unfavorable notice.

Clearly, this doesn't add up to serious competition for the Karajan set-or even, for that matter, for Leinsdorfs less strong y cast recording, which benefits from its conductor's strong structural grasp: In no other recording is the second trio of nymphs (announcing the approach of Bacchus) so cleanly detailed and firmly limned. If you must have stereo, this is the current choice, and perhaps you will feel that Leonie Rysanek (Ariadne) makes up in enthusiasm for her frequent vocal unkempth. In my own view, Ariadne is such an absurd, pretentious, and stylized conception that it only works if delivered with a maximum of elegance, which means Karajan, though the 1944 Bohm and the Kempe, among the deleted sets, do pretty well in this direction.

Less pretentious, because it gives the final word to the comedians rather than to the straining heroics of Bacchus, is the original 1912 Ariadne, written to be played with the Moliere-Hofmannsthal Burger uls Edelman!). The Beecham Society has circulated a 1950 Edinburgh performance; neither complete nor very well recorded, this is enjoyable for the astonishingly accurate Zerhinetta of Ilse Hollweg (though she skips some of the famous extra difficulties of this version) and the strong, unusually youthful Bacchus of Peter Anders. But this is no substitute for a complete and modern set; next time someone is thinking about recording Ariadne, why not try that version?

STRAVINSKY: Petrushka (1947 version). Concertgebouw Orchestra, Colin Davis, cond. PHILIPS 9500 447, $8.98. Tape: 7300 653, $8.95.

STRAVINSKY: Petrushka (1947 version). Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Christoph von Dohnányi, cond. [James Mallinson, prod.] LONDON CS 7106, $8.98. Tape: ' CS5 7106, $8.98.

Comparisons: Boulez/N.Y. Phil. (1911) Col. M 31076 Ansermet/Suisse Romande (1911) Lon. CS 6009 Stravinsky/Columbia Sym. (1947) Col. MS 6332 Levine/Chicago Sym. (1947) RCA ARL 1-2615

Christoph von Dohnányi's recording seems uncomprehending about Petrushka's style and texture. The engineering renders every line consistently audible-without distracting zooming in to pick up now this instrument, now that strand-but little attempt has been made to balance orchestral dynamics so that important events in the harmonic and melodic scheme stand out properly. The characteristic trumpet-dominated color so essential to the Petrushka sound has been slighted in heavily scored passages, and yet when instrumental solos come along (e.g., the trumpet for the Ballerirla's entrance in Tableau Ill or the high clarinet writing in the "Bear Dance" of the last tableau) the playing is so beefy and charmless it doesn't seem as if one was missing anything before. Dohnányi sets reasonable tempos but is rhythmically stodgy, and the side break unfortunately comes within Tableau Ill (before the waltz) rather than between Tableaux II and III.

Philips provides equally transparent and un-gimmicked sonics in its new Petrushka, yet with a musically discriminating balance so that one hears a Stravinsky instead of a Brahms orchestra. The Concertgebouw's virtuosity yields nothing to the Vienna Philharmonic's, and so much more grace and wit comes with it. Colin Davis generally heeds the composer's markings closely and displays control and vital energy in his interpretation, but I want something more in this music: a certain jaggedness in the rhythm that can't be precisely written in; a regretful trailing off in the ambiguous closing pages as Petrushka's apparition fades away (this is written in, but Davis ends firmly and unwaveringly); a sense of pathos and clumsiness in the two central tableaux.

Several of the numerous important Petrushka recordings realize some of these qualities. I still return to the composer's barbed and febrile reading with pleasure, though the playing is frequently ragged. Levine duplicates Stravinsky's driving intensity with greater orchestral precision, but RCA's recording is hardly ingratiating. Ansermet's enduring rendition of the original.

1911 version (the textual differences are pretty minor) is deeply compassionate and whimsical, tonally fresh, and bittersweet as a hurdy-gurdy. Though mildly artificial in its sonic perspective, Boulez' recording (also 1911) combines in some degree everybody else's propulsion and wit and is organized in all dimensions with particular lucidity. That might well make it my basic recommendation, with Davis for those who must have the 1947 revision; both of these plus Ansermet will give you, in irreducibly minimal form, the essential faces of Petrushka.

A.C.

TANEYEV: Symphony in B flat; John of Damascus, Op. 1*. Alexander Yurlov Russian Chorus*, U.S.S.R. Symphony Orchestra, Vladimir Fedoseyev, cond.

ABC CLASSICS/ MELODIYA AY 67043, $7.98.

Sergei Taneyev (1856-1915) was a venerable musical figure in tsarist Russia and is still highly honored by the Soviets as a composer as well as pedagogue, yet he and his music are almost unknown in this country. There have been a few recordings of Russian origin available briefly: the last of these-a fine program of choral works conducted by Alexander Yurlov on Melodiyaf Angel (SR 40151, May 1971)-followed the others into limbo several years ago. Hence the present works would be welcome almost regardless of their executant and technical merits. But it's a joy to be able to report that both performances by the relatively young and enthusiastic conductor not only are most impressively dramatic. but are powerfully enhanced by first-rate engineering.

--------------

Gerhard Hüsch: A Voice to Reckon With

by David Hamilton

Best known to American listeners as the Papageno of the classic Beecham recording of Mozart's Die Zauberflote (Turnabout THS 65078/80). the German baritone Gerhard Hüsch (b. 1901) was also among the most eminent of Lieder singers. He made the first complete recordings of some of the major German song cycles, contributed to the Hugo Wolf Society series, and recorded substantial groups of songs by then-contemporary composers such as Hans Pfitzner and the Finnish Yrjó Kilpinen.

In its prime, during the 1930s. the Hüsch voice was a rich, well-knit lyric baritone, reaching easily up to G. somewhat less consistently down to the bottom of the bass clef. The color was basically darker than most German specimens of this type (such as Hermann Prey, the closest present-day equivalent): though fundamentally a French horn, so to speak. Hüsch could also muster the more brazen colors of the trombone. His articulation was forward, lively, and precise-in speech, almost affectedly so. but this clarity nicely matched the sung tone. yielding a remarkably natural binding of word and tone. Like Elisabeth Schumann. Husch always seemed to be simply singing words, not singing notes interrupted by consonants or speaking words with pitches in the middle. And the control of dynamics was equally masterful, the instrument capable of much timbral variety, the legato impeccable.

At his best, Hüsch was also an irresistible interpreter. For example, Schubert's "Lied emes Schiffers an die Dioskuren" in the present reissue: The richness of the tone and the fervor of the delivery define an expressive territory that isn't much heard from nowadays. (I suppose Gérard Souzay is the recent singer who comes closest to this combination of nobility and tenderness, but his vocal material was never in the same league.) Equally hors concours is Hüsch's performance of "Dosssie hier gewesen," an exceptionally difficult song.

The voice intrudes upon silence so gently yet firmly that the reverence due a special place is perfectly expressed. However soft, the tone retains its beauty and solidity. nor does the pitching falter in the tricky central stanza. The precision with which word and note are matched also defines magically the crucial rests, and thus the silence is as concrete as the sounds.

Two lesser-known songs. "Widerschein" and "Liebeslauschen," are quite as exceptional, and most of the other Schubert performances are good. "Stdndchen" begins uncertainly, then warms up; "Horch! I torch! die Lerch' " (with the inauthentic additional verses) is warm and spirited. The bite of the diction is compelling in "Der Doppelganger" and in "Erlkonig," though Hanns Udo Muller-a pianist of considerable sensitivity-isn't able to punch out the triplets in the latter song as urgently as one would like. Loewe's "Archibald Douglas" is invigoratingly clone; though allotted both sides of a twelve-inch 78, the ballad still had to be abridged slightly.

"An die Musik" misses on simple musical grounds: though Muller begins correctly, Hüsch seems determined to put the primary accents in the middle of the bars rather than at the beginning, and the result is just plain uncomfortable. A more complicated failure seems to me to mar the Brahms songs, and it's one that frequently complicates my response to Hüsch's singing. "Wie bist du, meine Kónigin" is a love song, but this singer is clearly more occupied with the lovely sounds he's making than with his "Kónigin." One is ever grateful for that gorgeous tone, that cultivated diction, that unfailing legato-but, especially in longer works, we eventually also sense a certain narcissism. There's nothing wrong with beautiful singing. God knows, but when we remain more conscious of the singer as vocalist than of the miller's boy, the winter journeyer, or the lovelorn poet, something is out of kilter. Even in such disparate personae as Papageno and Jesus (in the Ramin recording of Bach's St. Matthew Passion), the unvarying self-satisfaction is not far away.

Still, there are treasurable things in nearly all of Hüsch's recordings. Preiser's Lebendige Vergangenheit label has done well by his song recordings for HMV: the Schubert cycles are on LV 203 (Winterreise) and LV 204 (Die schóne Müllerin), while LV 105 includes Beethoven's An die (erne Geliebte, Schumann's Dichterliebe, and Schubert's Harfenspieler songs. The Kilpinen songs ( LV 80) were much admired in the Thirties, possibly because little other contemporary vocal music was then being sung this attractively; they now seem pretty hollow. On the other hand, the Pfitzner series ( LV 208), accompanied by the composer, stands out as perhaps Hüsch's finest work: "Zum Abschiede meiner Tochter" is vocally impeccable, interpretively imaginative, and moving beyond words, and most of the others are similarly masterful. At the piano, the old gentleman fumbles now and then, rolling his chords in nineteenth-century style, but one imagines that his presence served as a lightning rod for some of that self-esteem. (Preiser includes several unpublished sides from these sessions that were not on an earlier Electrola LP.) There's also an operatic collection (LV 76), which is but a sampling of a large catalog; particularly enjoyable is the "Waschkorh" duet from Nicolai's Merry Wives with Eugen Fuchs, conducted by Alexander von Zemlinsky (Alma Mahler's composition teacher and Schoenberg's brother-in-law). Hüsch's Italian arias (in translation) are both fascinating and infuriating, for he sings the "wrong" words with imagination and conviction.

Not yet on LP are the Wolf songs (and won't somebody do something about Herbert Janssen's recordings for that series as well?). I'm slightly annoyed that the present record omits just one of Hüsch's HMV Schubert recordings: "Der Wanderer," originally issued as the verso of "Der Musensohn"; not a compelling performance, but I imagine that most collectors would as soon have the whole series and make up their own minds.

In the early 1950s, Hüsch went to Japan to teach, and made more recordings, including two versions of Schubert's Schwanengesung. I've heard only the second; the fervor and authority are still present, sometimes movingly so, but the once-golden tone had turned to dry wood, with a wobble on sustained notes. These Japanese Victors are only for those who know the great Hüsch recordings.

All the Preiser reissues are furnished with the same biographical note, in German. Except for the Kilpinen songs, most 5f the texts and translations can be found in the Fischer-Dieskau collection of song texts.

GERHARD HÜSCH: Song Recital. Gerhard Hüsch, baritone; Hanns Udo Muler, piano.

PREISER LV 257, $8.98 (mono [from HMV originals, 1934-39] , distributed by German News Co.).

SCHUBERT: Der Musensohn; Standchen; An die Musik; Lied emes Schitfers an die Dioskuren; Widerscheln; Liebeslauschen; Dass sie hier gewesen; Horch! Horch! die Lerch'; Erlkonig; Der Doppelginger. Loewe: Archibald Douglas.

BRAHMS: Feldelnsamkeit; Wie bast du, meine Konigin.

------------------

John of Damascus (1884) is a magnificently expansive and diversified choral and orchestral setting of a Tolstoi poem, exceptional both for the beauty of some of it characteristically Russian unaccompanied choral passages and for the exultant drive of its intricately fugal finale. It reminds you that Taneyev, almost alone among Russian composers, was an avid student of the giant European contrapuntists of earlier eras.

The symphony is even more excitingly rich in thematic ideas and virile in sheer energy; it is so magisterial in formal construction and colorful scoring that its compose demands to be ranked high in the pantheon of the musical great. One realizes how much Rachmaninoff in particular must have been influenced by him-without however, emulating comparably taut control of both materials and his own emotions. Neither Tchaikovsky nor Rachmaninoff surpasses Taneyev in the imaginative exploitation of instrumental possibilities Yet perhaps the most remarkable characteristic of this music is that it is at once quintessentially Russian (at times as darkly somber as Mussorgsky) and distinctively individual, albeit with a combination of intellectual power and lusty humor unique among Slavic composers at least up to the time of Stravinsky and Prokofiev.

Only pedants will worry about the obscurities of this symphony's provenance Some major reference works in English make no mention of it at all; others mention it only as one of Taneyev's unpublished symphonies. There are two more of these dating from 1873-74 and 1884, respectively in addition to the so-called Symphony No 1, in C minor, Op. 12, of 1896-97, lately re numbered No. 4 in Russia (available in Eng land in a Rozhdestvensky recording, HMV/ Melodiya ASD 3106). The present work is labeled here as being in B flat major, al though it actually begins in B flat minor, and is claimed to be No. 4 in Byron Cantrell's jacket notes, although he supplies no date. To confuse matters further, Gramophone reviewer John Warrack not only places it as No. 2 in the sequence of four, but describes it as an unfinished work for which Taneyev never got around to providing a fourth movement-a notion undercut by the patent conclusiveness of the third movement and by the perfectly integrated holism of the symphony as it stands.

Few listeners who "discover" the composer of this provocative work are likely to be content with this much. They'll want an American release of the C minor Sym phony, plus some of the highly reputed chamber works. And we can at least dream of hearing Taneyev's magnum opus, the operatic trilogy Oresteia (1895) after Aeschylus.

R.D.D.

WAGNER: Das Liebesmahl der Apostete; Siegfried Idyll. Westminster Choir, New York Philharmonic, Pierre Boulez, cond.

COLUMBIA M 35131, $7.98.

Comparison--Das Liebesmahl: Morris/Symphonica of London Peters PLE 043 Had it been issued a year ago, this record would have elicited lively curiosity among Wagnerians intrigued by the prospect of hearing Das Liebesmahl der Apostel, an 1843 work for large male chorus and orchestra. But in the meantime, Peters International brought out Wyn Morris' excellent recording (reviewed in these pages November 1978), and our curiosity has been well satisfied: Das Liebesmahl demonstrates Wagner's proficiency in handling large forces, but is generally of more historical than aesthetic interest.

Of Boulez' version, at least, it may be said that it offers a choice, not an echo.

Whereas Morris takes thirty-three minutes to get through the piece, Boulez polishes it off in twenty-six. In general, Morris gets a fuller, warmer choral tone, and also a wider range of dynamics (and closer observation of Wagner's markings). For this reason, his performance appears to be more interesting, and holds the attention over its longer span better than the Boulez.

A minor advantage of the faster speed is that the whole piece fits on a single side, avoiding Morris' turnover shortly before the orchestra's entrance for the coda. But then Peters gives you an otherwise unrecorded-and rather good-Bruckner piece.

Helgoland, while Columbia offers only a fairly rebarbative performance of the Siegfried Idyll. This is played one instrument to the part, which is a good idea in principle--but chamber music playing is not the strong suit of these Philharmonic men. The rather clinical recording exposes an unfortunate quantity of steely string tone, erratic intonation, and unpleasant tutti sound.

D.H.

------------

Recitals ...

GERHARD HUSCH: Song Recital. For a review, see page 92.

WEISS FAMILY WOODWINDS. Dawn Weiss, flute; David Weiss, oboe; Abraham Weiss, bassoon; Zita Carno, piano. CRYSTAL S 354, $7.98.

Vivaldi: Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Bassoon, and Harpsichord, in G minor, RV. 103. MESEIAEN: Le Merle noir, for flute and piano.

BORDEAU: Solo for Bassoon and Piano, No. 1.

HINDEMITH: Sonata for Oboe and Plano.

The Romero family foursome remains unchallenged, but even the great Gomberg brothers and other familial musical pairs must defer to the Weiss siblings: David, currently co-principal oboist of the Los Angeles Philharmonic; Abe, principal bassoonist of the Rochester Philharmonic: and Dawn, a flutist with the Oregon Symphony.

It isn't merely their family relationship that makes this program one of the best of those I've heard lately in Crystal's recital series, although the kinship well may account for the combined precision and freedom of the 1

ensemble playing in the delectably cheerful yet songful Vivaldi sonata, which is new to me.

The individual Weisses' performances, each with pianist Zita Carno, are all first-rate, although perhaps only oboist David radiates magisterial authority. The selections vary widely in appeal, with Messiaen's rhapsodically improvisatory Blackbird and Bordeau's conservatory contest/ display piece of decidedly more specialized interest than Hindemith's better-known, vivacious oboe sonata.

The apparently quite close-miked recording cannot be faulted, nor can the disc processing. R.D.D. AUDIOPHILE RECORDS The unconventional techniques employed in the recording and manufacture of the discs reviewed below result in prices and distribution patterns that set them apart from mass-market recordings.

RIMSKY-Korsakov: Capriccio espagnol, Op. 34.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Capriccio italien, Op. 45. Boston Pops Orchestra, Arthur Fiedler, cond. [Ed Wodenjak, prod.]

CRYSTAL CLEAR CCS 7003, $14.95 (direct-to-disc recording).

PROKOFIEV: Love for Three Oranges: Suite.

RAVEL: La Valse.

FALLA: La Vida breve: Dance No. 1. London Philharmonic Orchestra, Walter Susskind, cond. [Ed Wodenjak, prod.]

CRYSTAL CLEAR CCS 7006, $14.95 (direct-to-disc recording).

GOULD: Spirituals for Orchestra; Foster Gallery. London Philharmonic Orchestra, Morton Gould, cond. [Ed Wodenjak, prod.]

CRYSTAL CLEAR 7005, $14.95 (direct-to-disc recording). (Crystal Clear Records, 225 Kearny St., San Francisco, Calif. 94108.)

What impresses me about these three discs is their lack of sensationalism, their freedom from sonic smudging-in short, the concert-hall authenticity of their timbres, dynamics, tonal balances, and perspectives. Everything here seems as natural and real as in live performances heard from midway back in Boston's Symphony Hall and in London's Watford Town Hall.

One very good explanation for this lies less in the technology involved than in the fact that the recording engineer for all three programs is Bert Whyte, whose early stereo recordings for the original Everest company remain milestones of audio progress.

Here, of course, he can draw upon some twenty years' technical advances, to say nothing of the elimination of tape masters and a couple of generations of sub-masters, plus exceptionally careful disc processing.

Yet I doubt that any of these factors contribute as much to the results as Whyte's ear and aural taste.

Granted, the direct-to-disc technique's greatest handicap-the necessity of getting everything right the first time-does result in some executant constraints. Even the ever exuberant Arthur Fielder seems uncharacteristically over-serious, while Walter Susskind never achieves the full elasticity and sinuosity demanded by La Valse.

Only Morton Gould, conducting his own music. which is more slapdash in nature anyway, seems relatively free from inhibitory tensions.

But any real or imagined constraints are quite minor shadows on the luminosity of Fiedler's capriccios, each of which must rank among the best of the innumerable recordings. It's good too to get such splendid new versions of the relatively neglected suite from Prokofiev's Love for Three Oranges and that favorite symphonic encore of 78-rpm days, the Dance No. 1 from Falla's Vida breve. Old and new Gould fans will be equally delighted by the first modern recordings of his long forgotten divertissements on Stephen Foster tunes and of his once popular Spirituals for Orchestra.

For me, these works have aged less gracefully than his ever-delectable Latin American Symphonette, yet they are so rich in ingenious orchestral sound effects that they handsomely demonstrate the recording to technique's sonic authenticity, lucidity, at d rock-solid percussive lows.

he Susskind and Gould recordings (made late in 1978) boast, as the Fielder (made late in 1977) does not, of being "supercut ... using the Ortofon extended range disc mastering system," though I don't hear any appreciable improvement. At high playback level none of these discs' surfaces, exceptionally smooth as they are, is absolutely noiseless, which gives me--as a tape connoisseur--some wry satisfaction: until home digital playback of digital recordings becomes practicable, the closest approach to the elimination of surface and background noise remains the best Barclay-Crocker Dolby open reels and the best Advent and ln-Syn Dolby chromium-base musicassettes.

R. D. DARRELL

---------------

Also see:

It's Superman! (John Williams)