How to find out and what to do about it if they are.

Part I: Classical Records

by Michael Biel [Michael Biel, who has conducted research and archival projects in the fields of early recording and radio, is assistant professor in radio-television at Morehead ( Kentucky) State University. ]

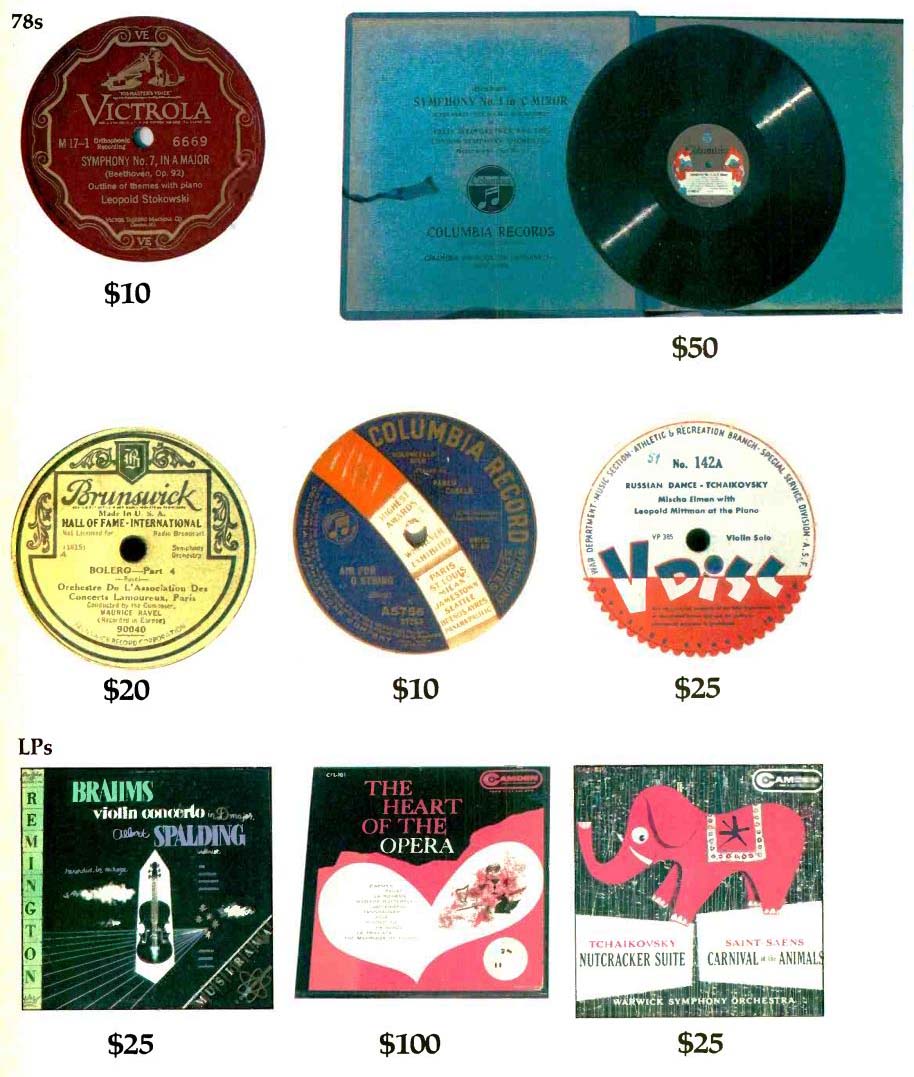

Above: top row: Stokowski speaks! Since the single-sided "outline of themes with piano" is often missing from sets of Stokowski's early electrical recording of Beethoven's Sym phony No. 7 on Victrola, collectors are constantly looking for it. Columbia's five-disc acoustical set of Felix Weingartner conducting the Brahms First Symphony was short-lived-and thus is rare-because it was issued just before the electrical era and priced high for the mid-1920s: $8.75 for the set.

Middle row: Ravel's two-disc recording of his Bolero on Brunswick, dating from the early 1930s, is not as valuable as the original European Polydor pressings. Cellist Pablo Casals' Columbia record of Bach's Air for G String came out of the 1915 recording session documented in the log card displayed on page 64 of last month's issue. On the V-Disc, Mischa speaks! V-Discs were recordings sent to armed forces bases during World War II. The rare ones that turn up in top condition command premium prices, especially when, as in the Mischa Elman disc shown here, they are not dubs of commercial recordings.

Bottom row: Don Gabor's budget label, Remington, produced many now sought-after items like this Albert Spalding recording. The two Camden reissues from 78s are each now worth considerably more than the originals, although none of the artists is named. "The Heart of the Opera," a six LP set, first appeared on the mail-order World's Greatest Operas label in 1940.

Among the anonymous artists are singers Eleanor Steber, Leonard Warren, Norman Cordon, and Vivian Della Chiesa and conductors William Stein berg and Wilfred Pelletier. The poorly dubbed Nutcracker Suite/Carnival of the Animals has value because the "Warwick Symphony Orchestra" was the Philadelphia Orchestra led by Stokowski.

------

The leading attribute of classical music is supposed to be its staying power. It does not become dated, as pop music does. Furthermore, the major characteristic of the phonograph is its ability to preserve sounds permanently.

Yet, many owners of classical recordings periodically find it necessary to discard their collections and replace them with new ones. Why? Certainly not because of the subtle changes in performing styles. Rather, the main reason has been revolutions in technology, as when electrical recording began in the mid-1920s, when high fidelity microgrooves replaced electrical shellac 78s in the 1940s, and ten years later when the stereo disc was introduced. Today's noise reduction, direct-to-disc recording, digital taping have thus far been only means back to our familiar stereo LP format. But with the totally incompatible digital disc looming on the horizon, once again it is time to ponder that agonizing question:

To save or not to save? Reviewer Robert C. Marsh shocked many collectors when he asserted in these pages in July 1973: "I am inclined to regard any recording more than five years old as obsolete technically. This doesn't mean that it is not to be played or admired, but it ceases to be competitive with contemporary work.

The listener should be told you are talking about the sonic counterpart of a 1968 car." Marsh assumes that all record companies were at the same plateaus in both 1968 and 1973 and that all 1973 recordings were automatically sonically superior to all those from 1968. At the other extreme, some listeners still are inclined toward the Mercury Living Presence single-microphone discs made a quarter-century ago, and some very rare collectors (mostly British) still prefer acoustical recording and reproduction.

Whatever the reason, some of you music lovers are looking for a remunerative way of disposing of your old classical recordings-and perhaps there are collectors frantically seeking just the ones you have. The hard part is finding the person who wants what you have and determining its worth. First, let's divide the collection into four categories: orchestral; solo instrumental, chamber music, and concertos; solo vocal and operatic arias; and complete operas.

The acoustical recording system responded less well to orchestras and the female voice than it did to solo instruments, small instrumental groups, and the male voice. The most famous name from this period is Enrico Caruso, but his discs sold so well-and have been treasured and saved by so many-that few of them are scarce. So those Caruso records you found in your grandmother's attic are probably not valuable (unless they are Zonophones with pale blue labels, center-start Patties, AICC cylinders, or Gramophone and Typewriter labels).

The prize acoustical recordings are those that date from before 1910. Scarcity is a large factor here, but the historical importance of early or only recordings by certain artists is not to be overlooked.

Almost any pre-1906 disc in mint condition by a name artist is likely to bring in $10-$15, and, if you have any of the old Columbia’s featuring basso Edouard de Reszke, you might get $375 or more. For discs in only average condition, divide prices in half.

When electrical recording made reproduction of orchestral music more feasible, there was a great effort to build a recorded orchestral repertoire. Some of the early examples are sought after because they are rare, but most of the 78-rpm sets of standard fare are very common. Besides, collectors of early recordings place great stock in the individuality of performances. Orchestral recordings rank very low in this area because the conductor, the predominant force, has to route his interpretation through a hundred other musicians. One recording of a particular symphony is pretty much like the others. Though there can be significant differences in interpretation, you are sure to find one you like from any decade since the microphone, and since the sonic experience is a major ingredient in the enjoyment of orchestral music, this genre is the most likely to suffer from a technically inadequate recording.

Thus, there is little call for old orchestral recordings, especially those made before 1950, unless they are interpretively or historically important. Remember, then as now, plenty of duds were recorded.

Complete operas are not much in demand either, despite the individuality of any vocal performance. Again, a conductor guides the proceedings, and, while a lead might be sung by a vocalist of note, the rest of the cast probably is not first-rate. During the era of the 4 1/2-minute 78-rpm side, opera sets often comprised twenty discs, and when an opera is interrupted thirty-nine times, you start to wish that Colline would smother the coughing hag with his over coat or root for the high priests to hurry up and seal the tomb on Aida and Ra dames. For these and other reasons, recordings of whole operas were not numerous before the LP, and the notable ones have generally been reissued on LP.

Most opera lovers were content to purchase their favorite arias sung by their favorite artists.

Solo instrumental and concerto recordings are in as much demand as solo vocal discs-the skills and interpretive values of the performer are as personal as a fingerprint. Sparked by the interest engendered by the International Piano Archives, there is a worldwide search being undertaken by many collectors for all types of piano recordings. Practically no pianist is overlooked no matter how obscure. Violin discs are a little more abundant, and as yet there is no demand for representation by every fiddle player. Sarasate, early Kreisler, and Spalding, yes; Heifetz, later Kreisler, and Zimbalist, generally no. (A complete set of the handful of recordings made by Pablo Sarasate was recently announced at $2,000.) Pablo Casals' discs are fairly plentiful and not too expensive, but those by other cellists are becoming costly. Other instruments have not attracted such cult attention, so prices have not been driven up. But their scarcity at least preserves their value. This is especially true for most pre-LP chamber music recordings.

$75 --- The 1955 issue on RCA Victor LM 1922 of "The Sounds and Music

of the RCA Electronic Music Synthesizer" may not have been a big hit at

the time, but collectors now treasure it as the world's first recording featuring

a music synthesizer. Composers featured range from Bach to Irving Berlin; the

liner notes had to start on the front cover in order to fit.

Most dealers agree that it is almost impossible to sell many of the 78 orchestral sets, particularly from the 1940s. Conductors like Serge Koussevitzky and Leopold Stokowski who have an avid following sell very well; Arturo Toscanini recordings don't move very fast only because they are so common. A well-produced reissue can kill the value of the original recording, particularly if the original was itself an LP. Occasion ally the reissue has greater worth than the original. Some early Camden LPs of anonymous conductors leading such pseudonymous ensembles as the War wick Symphony, the Centennial Sym phony, the Festival Concert, and the Stratford Symphony Orchestras are fetching $25 even though they are poorly dubbed, because the first is really the Philadelphia under Stokowski, the second the Boston under Koussevitzky, the third the Boston Pops under Arthur Fiedler, and the last the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Koussevitzky and others. And the interest in performers in creases dramatically following their death, as happened with Fritz Reiner and George Szell and may be about to hap pen with Fiedler.

Early LPs can be valuable if the performance was exceptional and never issued in any other form. Sometimes the most unlikely candidates for immortality garner high prices. A record on the old budget label Plymouth (P 12125) went for $250 not long ago: Chopin waltzes played by Etelka Freund, a pupil of Brahms's and an intimate of Bartok's.

Carl Friedberg's Brahms and Schumann piano works on Zodiac 1001 has sold for $60, and premium prices may be had for early LPs by Mischa Elman, William Kapell, Albert Spalding (on Remington!), Marguerite Long, and Willem Mengelberg with the Berlin Philharmonic and Concertgebouw Orchestras. The first synthesizer recording, RCA Victor's 1955 "The Sounds and Music of the RCA Electronic Music Synthesizer," has changed hands for $75.

In some cases the labels them selves are the attraction. There is one valiant collector who is determined to get every RCA Victor LM and LSC record ever released. The early LP period was rich in major labels that dedicated themselves to serious music and then deleted entire series containing hundreds of albums-Capitol, MGM, and Decca come to mind. For the same reason, old 10-inchers are usually sure bets to be collectible. The August 1956 issue of SCHWANN is ample evidence of how suddenly the small record was eliminated from the marketplace. On almost every page there's at least one black diamond for RCA's 10-inch records alone. It should be remembered, however, that the demand for a mono LP diminishes if it has been reissued and is almost nil if it was released originally in real stereo as well as mono.

Up to now, we have studiously avoided mention of anything other than commercially released discs. Test pressings of unissued recordings or alternate takes can be valuable if the artist is significant. One Japanese collector recently paid $500 for five Toscanini test pressings made by the Arturo Toscanini Society, which was banned from issuing the recordings. Air checks, bootleg con cert recordings, instantaneous discs, and tapes are difficult to evaluate. In some in stances, the Internal Revenue Service has fixed value of amateur home-recorded tapes and lacquer discs at the cost of the raw, unrecorded item. There is no intrinsic value of a first-generation air check when dubs can be made virtually indistinguishable from the original. Market value can be placed on an item only when it or an identical edition changes hands.

The condition of the discs is vital.

Excessive surface noise and scratches will blot out pianissimos, and the first evidence of wear is a fuzzy fortissimo.

Most collectors are not looking for an original issue just for the thrill of being the proud possessor of the "first edition." They are looking for the best-sounding pressing. Sometimes the first pressing is the best-sounding, but if postwar shellac will yield less surface noise than the "regrind" garbage used during the war, then the later pressing will be more desirable. Generally, discs of serious music have been treated with greater care and played on better equipment than those containing other kinds of music. And many companies used a better grade of shellac or vinyl for such pressings and exercised stricter quality control. But certain grades of shellac are more prone than others to develop crackle from damp storage conditions.

English HMV shellacs are notorious for this problem, although they were highly prized when they were new. Owners of shellac discs are urged to read John Stratton's devastating article "Crackle" in the July 1970 issue of Recorded Sound, CEM.s.

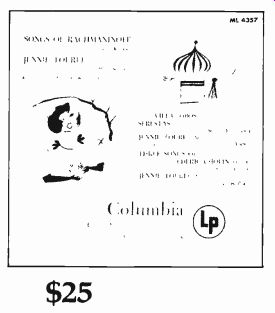

$25---This Columbia LP (ML 4357) of Jennie Tourel singing songs of Rachmaninoff,

Villa-Lobos, and Chopin dates from 1950, just two years after the company introduced

the long-playing format to the world of music lovers. The artwork is typical

of that provided by Columbia during the early LP era.

No. 39, published by the British Institute of Recorded Sound-and to buy a dehumidifier.

Just as the market for new classical recordings is only about 5% of all record purchases, the market for older ones is comparably small. If you have a modest collection that you would like to sell, you are not likely to easily dispose of it, much less make a profit. Remember, an old record is a used record. You are dealing with a consumable item that depreciates with age and wear. You might not be able to sell most of your classical 78s for more than 254 to 50c, although it will cost you $2.00 to $3.00 apiece to buy the same discs from a specialized dealer.

You might have a few $10 or $25 items in the batch, but the majority would be un salable or hardly worth listing in a catalog. A small number of collectors looking for the same disc may drive the price up-until everyone finds a copy.

If you have a large collection and are dismayed at the prospect of letting all your "gems" go for a quarter each, you might sell them yourself and let a dealer take the leftovers. Just don't be surprised if he doesn't want them-your leftovers will probably become his left overs, and he knows it. The question is, do you need the money and /or the space now? Or are you willing to take the time to advertise and investigate? An ad in a metropolitan newspaper may turn up enough buyers to clean you out with relatively little bother. More likely, you will need to proceed to other journals with national circulation, including those specifically published for the purpose. [See box on next page.] Putting ads in newspapers of colleges--especially those that have a good music curriculum-might be productive. If the young are sometimes scornful of the past, they are often the most appreciative purchasers of older recordings. The beginning collector is not apt to have a lot of money to spend, but this is a ready market for even the commonplace items.

If you don't mind settling for the joy of giving-or a tax deduction-in stead of cash, there are many libraries and music schools that might be good targets for your collection. (Be prepared to demonstrate to the IRS that an old 78 is worth more than a half-dollar.) If they have an archival collection, like Yale, Stanford, and Lincoln Center, they probably already have copies of most of your recordings. Many archives have multiple copies that are circulated among other libraries or are used for fund-raising. Or you might donate your discs to a charity bazaar or thrift shop. There are plenty of collectors who still frequent thrift shops-and many can relate stories of extraordinary finds for a dime or a quarter. Incidentally, for the sake of collectors, if you choose one of these places, check to see how the discs already in stock are handled. If they are thrust into bins that will destroy them, donate your records elsewhere.

After all your research and appraisal, the potential worth of a specific disc may not mean a thing. Ultimately, it is worth only what someone is willing to pay for it. And while the potential value of some items might be hundreds of dollars, people who will pay the price are often rarer than the records themselves.

----------------

Aids in Selling

Where to Sell

You can find names of dealers in jazz and blues recordings in Vintage Jazz Mart (4 Hillcrest Gardens, Dollis Hill, London NW 2 6HZ, England).

Though published abroad, this thick magazine is packed with ads for U.S. dealers. And you can find ads for 78s-or advertise some yourself-in U.S. publications such as Antique Trader (P.O. Box 1050, Dubuque, Iowa 52001), Collector's News (P.O. Box 156, Grundy Center, Iowa 50638), and Hobbies (1006 S. Michigan Ave., Chicago, Ill. 60605); for 45s and LPs, Goldmine (P.O. Box 187, Fraser, Mich. 48026), Kastlemusick Monthly Bulletin (901 Washington St., Wilmington, Del. 19801), and Record Exchanger (P.O. Box 6144, Orange, Calif. 92667). Dealers' names can also often be found in the classified ads in this and other record journals.

A selection of those who deal in out-of-print classical records follows:

Figaro's, 1287 Cambridge St., Cambridge, Mass. 02139. LPs only.

Lawrence F. Holdridge, 54 E. Lake Dr., Amityville, L.I., N.Y. 11701. Auction lists of the highest-quality, most rare vocal and instrumental 78s, All bidders, successful or not, receive a listing of prices realized on auctioned records.

Immortal Performances, Jim Cartwright, P.O. Box 8316, Austin, Tex. 78712. Occasional auction and set-price lists covering all types of serious music, 78s, and LPs, plus detailed discographies of selected artists.

Arthur E. Knight Collection (formerly Dom Art Collection), 128 Fifth St., Providence, R.I. 02906. Monthly lists of vocals on 78, 45, and LP.

S. A. Langkammerer, 3238 Stoddard Ave., San Bernardino, Calif. 92405.

Nipper, P.O. Box 4, Woodstock, N.Y. 12498. Will remove you from mailing list if they don't hear from you every four months.

Parnassus Records, Les Gerber, 2188 Stoll Rd., Saugerties, N.Y. 12477.

Price lists and search service for micro groove issues only.

Polyphony, 120 N. Oak Park Ave., Oak Park, Ill. 60301. Free lists of new and used LPs.

The Record Undertaker, Steve Smolian, R.D. 1 Box 152C, Catskill, N.Y. 12414.

Ross Robinson, 40 E. Ninth St., New York, N.Y. 10003. No 78s, and only LPs in top condition.

Spicer, 3283 Lonefeather Crescent, Mississauga, Ont. L4Y 3G6, Canada.

Lists of 78s and LPs.

Frederick P. Williams, 8313 Shawnee St., Philadelphia, Pa. 19119.

Will compile lists on request.

T.B. and M.B.

Price Guides

To help you estimate the value of individual records, there are several reasonably accurate price guides available.

Jerry Osborne and Bruce Hamilton have a series of "Official Prices Guides" covering rock, country and western, and al bums, as well as A Guide to Record Collecting, basically selected excerpts from the others. They can be found in book stores or ordered from Jellyroll Productions, Inc., P.O. Box 3017, Scottsdale, Ariz. 85257. Another recent publication is The Official Price Guide to Collectible Rock Records by Randal C. Hill (House of Collectibles, Inc., 773 Kirkman Rd. # 120, Orlando, Fla. 32811). The two rock guides are similar in pricing and coverage, though where valuations differ Osborne- Hamilton is usually higher. It also gives more information on the differences in label types and pressings and provides the release date of each record;

Hill includes short artist biographies.

For classics, the sole published price guide is limited to U.S. releases of acoustic 78s recorded by "celebrity" artists: Julian Morton Moses' Price Guide to Collectors' Records, $9.95 for thirty-two pages. Originally published in 1952, its "third edition" in 1976 merely included a chart with which to convert old prices to new (American Record Collectors' Ex change, P.O. Box 2295, New York, N.Y. 10017).

There is even a price guide for the color picture jackets in which some 45s originally came-not the records, just the jackets. It is The Collector's Price Guide to 45 RPM Picture Sleeves by Lloyd, Ron, and Marvin Davis (Winema Publications, P.O. Box 172, Medford, Ore. 97501). Unfortunately, no one has yet compiled an even marginally reliable listing for pop 78s. (There is one called 78 RPM Records and Prices, but it is dreadful.) Values often are overstated in such publications, presumably because that is what their readers want to see. Osborne-Hamilton, for example, lists nothing at under $1.00, and Moses' minimum price is $2.00, although in any box of oldies there will be many that you can't give away. But the guides may help you to spot the occasional rarity.

This tendency to overvaluation makes price guides quite controversial among collectors, mainly because they leave sellers with unreasonable expectations and thus inhibit transactions. Norm Cohen, writing in the John Edwards Memorial Foundation Quarterly at the UCLA Folklore Center, tells the story of a well-known price guide writer of the 1940s, Will Roy Hearne, who was also a mail-order dealer in old records. His listings were generally regarded as high, per haps being designed to enhance the value of his own stock. On one of his shopping expeditions in the South, Hearne came upon a warehouse full of mint 78s. When he asked the price for the entire lot, the owner whipped out a copy of Hearne's own guide and began quoting $5-$10 prices for every disc. "Hell, I know the fellow who wrote that book," Hearne interjected, "and every bit of it is non sense." But he didn't get the records.

T.B. and M.B.

---------

Part II: Popular Records

by Tim Brooks

[[Tim Brooks is a vice president of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections. He co-authored The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network TV Shows, 1946-Present, recently published by Ballan tine Books.]]

In December 1898, a magazine called The Phonoscope reported to its readers, "Old records are now in great demand by enthusiasts who aim to possess valuable collections." Since commercial recording was less than ten years old at the time, "old" obviously did not mean what it does now. Today there is a large network of collectors specializing in everything from original, individually made wax cylinders of the 1890s to Lesley Gore 45s of the 1960s. The most activity probably centers around rock and rhythm and blues of the past thirty years, followed by classic jazz and blues discs of the 1920s and '30s. Smaller constituencies pursue old country/folk records, big bands, pre-1925 acoustic recordings (disc and cylinder), and early Broadway cast and movie soundtrack LPs.

Collecting old records is not an ex pensive hobby, which is what makes it attractive to many. Though occasionally prices paid are high, they are in no way comparable to those charged for rare stamps, coins, or books. But that may be changing.

Just a few years ago a 78-rpm disc that once sold for 75e brought a cool $4,000-the highest price ever paid for a single record. If you happen to have an original copy of "Zulus Ball" by King Oliver and His Creole Jazz Band on Gennett 5275 (recorded in 1923), you too could be rich. If not, perhaps you could turn up a nice original pressing of "Stormy Weather" by the Five Sharps on Jubilee 5104 (also a 78, from 1952).

----------------

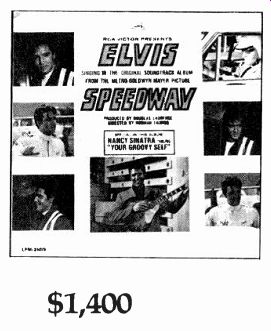

$1,400 - Guidebook author Jerry Osborne has estimated a more than tenfold

in crease in price for a mint copy of this Presley soundtrack LP since the

singer's death. It is only the mono version, LPM (not LSP) 3989, of the twelve-year-old " Speedway" that

is so expensive because it was Elvis' last album to be issued simultaneously

in both mono and stereo and at the time RCA was pressing few discs in the

waning format. Only three copies are known to collectors, although many more

are undoubtedly collecting dust on shelves around the world.

-----------------

Only one unbroken copy is known to exist, and that one sold for $3,866 at auction in 1977.

The current hot item that every one is looking for is a 1956 radio inter view disc, "TV Guide Presents Elvis Presley" (RCA Victor EP G8 MW 8705).

It is a one-sided 45 containing the singer's answers to four questions, which are supplied on a "continuity sheet" (so the local disc jockey could read them on the air), along with another insert that tells the story behind the interview. It is worth perhaps $3,000 complete. But be careful, there are counterfeit copies around.

Despite the sought-after rarities, and the visions they conjure up of easy money for what you may find in the closet, most old records are not worth the vinyl or shellac they are pressed on.

You can get a quarter apiece for them if you're lucky. But how do you tell what's valuable and what's not, and how do you go about selling those you wish to convert to cash?

Let's take a look at the box of old discs you've found. As with any specialized field, it's impossible to become an expert in one easy lesson, but a few guideposts may help. There are three factors that may tell which might be worth some money:

1. Condition. A pop record that is cracked, gouged, or so scratchy that the noise drowns out the music is not going to sell to anybody. Unlike ancient Greek pottery, it isn't worthwhile to piece bro ken records together.

2. Type of music. As a rule, jazz, rhythm and blues, Broadway cast recordings, and the like bring more money than other kinds of pop music.

This is true for 45s, 78s, and LPs. If you have a stack of old blues shouters, jazz bands, or 1950s r&b groups, you may be in luck. If all you have is Margaret Whiting--sorry.

3. Familiarity. Do you seem to re member that most of the discs you're looking at were big hits way back when? Presley's "Hound Dog," Glenn Miller's "In the Mood," or Gene Austin's "My Blue Heaven" may make good listening (depending on your vintage), but they originally sold so many copies that they probably won't bring much today. I once asked a knowledgeable collector friend whether Paul Whiteman's 1920 Victor recording of "Whispering" had really sold a million copies. He replied, "I think I've been offered that many myself." Of course if you don't recognize the titles and artists as you flip through your collection, that doesn't necessarily mean they're valuable. But familiarity is a bad sign. An exception to the rule is the occasional combination of the familiar and the obscure, such as the rare early release by an artist who later became famous. Don't bring me your standard RCA pressing of "Heartbreak Hotel," but if you have one of the early Sun recordings by Elvis, come right in! Original copies of these legendary Sun 45s and 78s are selling in the $100-$300 range, some even higher. But find an ex pert to tell the difference between the real thing and a bootleg reproduction.

Which pressing you have of a hit record can, in a few cases, be important.

One recent price guide lists ten different versions of the Beatles' "Please, Please Me," ranging in value from $1.25 to $250.

A few widespread misconceptions should be eliminated right now. For one, age is not a factor. Those 12-inch Victor Military Band 78s from before World War I (usually labeled "For Dancing") can't be given away, while some unusual Beach Boys 45s from the 1960s might bring $100. On the other hand, an LP of John F. Kennedy speeches from the Six ties may be worthless, while a 1912 Edi son cylinder recording of Teddy Roosevelt could produce $40 or $50.

One-sided records are often thought to be very old and therefore valuable. The fact is that single-sided records were made and widely sold until 1918 (by Sears, Roebuck, under its Ox ford and Silvertone labels). Victor's prestigious Red Seal classical discs, which remained one-sided until 1923, bring no special premium.

Some people are convinced that the physical appearance of a 78 is a dead giveaway to its rarity and thus its value.

Not usually. The thick Edison discs, for example, have no special worth. Old Man Edison ran his record company as a kind of personal indulgence, with little sense of what was popular or even interesting in music. He turned out hundreds of se date instrumental solos and duets, non descript tenors singing "I'll Take You Home Again, Kathleen," and at least a dozen versions of "Nearer My God to Thee"-not likely to excite today's collector. A few jazz bands in the late 52000 series might be worth something, but that is because of their content.

Another odd form frequently found is the cardboard Hit of the Week discs produced from 1930 to '32. They were originally sold on newsstands for 15c apiece, a new title being distributed every week in a novel attempt to revive the Depression-ravaged record industry.

It worked for awhile but eventually collapsed-even 15¢ was too much to spend on records in 1932. Little jazz was re corded, and no blues. Instead, the emphasis was on dance versions of current hits. There are a lot of them still around.

One format that is prized is the picture disc, which has been produced sporadically for many years. There has been a good deal of collector interest in these lately (quite apart from the industry's recent abortive attempt to rejuvenate them). Probably most famous are the Vogue Picture Records of 1946-47, which have a full color drawing under the surface on each side-rather garish, 1940s "coal company calendar art," one publication called it. Virtually unbreakable and very well recorded for the period, they are going for $5-$10 each.

Even more valuable are editions made by Victor in the early 1930s, especially "Cowboy's Last Ride" by Jimmie Rodgers (18 6000), with a big picture of the father of country music on one side. About a dozen copies are known to exist. Rumor has it that a bid of $400 failed to win one offered in a recent auction.

-------

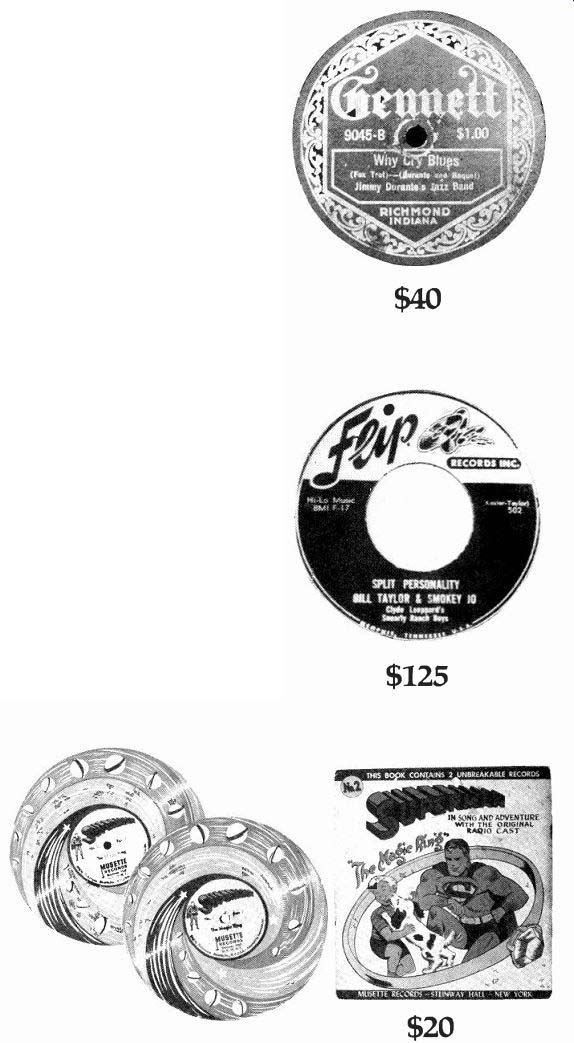

Jazz critic Rudi Blesh once called Jimmy Durante the greatest white rag

time piano player before he became a co median; the 1924 Gennett recording

of Jimmy Durante's Jazz Band is perhaps the only example of the Schnozzola's

musical career during the early 1920s.

(He did make later piano recordings--including one for RCA Victor Red Seal with Wagnerian soprano Helen Traubel!) Don't overlook 45s or children's records either, as the country music "Split Personality" and Superman discs demonstrate. The latter are actually laminated paper 78s that came with a twelve-page illustrated script. The "original radio cast" included Bud Collyer and Jackson Beck. You could probably get considerably more for this 1947 package from the large market of comic-book collectors, especially if the booklet and jacket are in good condition.

The 10-inch Capitol LP at the top of the next page is possibly Jackie Gleason's least-known record. On it he sings songs as six of the comedy characters he portrayed in his early-'50s TV series. At the time "The Dick Powell Song Book" was released in the late '50s, Powell was known in the country mainly as a TV private eye. The LP is still the only reissue of the best of his Decca 78s from the '30s. The final item here is--that's right--Yul's sister. Collectors seek it as a companion to her brother's Vanguard album of Gypsy songs.

----------

"Little" 78s, usually 7 inches in diameter (same as a 45, but without the large center hole), also tend to earn a premium. Most were made in the early days-in fact, the very first discs sold in the U.S., in 1894, were 7-inchers (and single-sided). Generally these "E. Berliner's Gramophone" records sound dreadful, even by 78-rpm standards, but they will garner $10 apiece anyway.

There are other sizes as well, from 5 inches up, and you can usually sell them for somewhat more than ordinary 10- or 12-inch 78s; those 14 inches or larger, are valuable also but seldom found.

Cylinders sell for at least a dollar or two, and often more, no matter what the content. The later (post-1912) blue celluloid Edison cylinders are virtually indestructible, but the earlier wax ones are fragile: If they don't break, they grow mold. Don't forget those circular containers, with the nice picture of Edison on the side. Even if the cylinder has disappeared, they make dandy pencil holders.

If you think you have something of value, there are several routes you can follow. The best is to sell to, or through, an established dealer. If you are convinced that yours are "money" records, ask for a consignment sale via auction, in which you get an agreed percentage of the selling price. Most dealers will do this only with genuinely valuable records, but it can work very much to your advantage, because you may collect 70% or more of the price. Some dealers use a sliding scale, taking a larger percentage of the winnings for low-priced discs and a smaller bite from higher-priced ones.

Formulas vary widely, so shop around.

Or you could sell the collection to him outright. You won't get top dollar per disc, but the total should be respectable.

Again, approach more than one dealer.

Competition can do wonders, and the experience could give you a better idea of what your records are really worth.

You can sell them yourself, of course, but you should try it only if you have a knowledge of the field-or if you crave adventure. For a onetime sale the time and aggravation will probably not be worth the cash realized, if any. Assuming you're going to sell by mail and through competitive bidding, there are several things you have to do.

First, prepare a detailed list of the records you want to dispose of, including title, artist, label, and manufacturer's number for each. Don't go into lengthy descriptions of how dear to your heart they are.

Next, since the prospective buyer can't see what he is getting, each disc's condition must be fairly and objectively evaluated. Collectors use a detailed grading system, which is outlined in such publications as Vintage Jazz Mart and Goldmine. It is to your advantage not to overrate your records. If the buyer disagrees with your judgment, you may have to return his money and start all over again.

Advertising is expensive and is useless unless you know where to place the ads. Try a magazine that attracts record collectors, like this one or, with even sharper aim-and cheaper-one of the collectors' publications listed here.

Once you have a buyer, you face the chore of packing and mailing. There is a science to preparing records for shipment, and it's especially important when handling fragile 78s. Records cannot be insured against breakage, and you are the one who will take the loss. The best way to learn about packing is to buy a few discs from established dealers and see how they do it.

Before you go through all this, give those oldies another listen. Maybe you'll decide to keep them. After all, Margaret Whiting did have a nice voice.

(High Fidelity, Jan. 1980)

Also see: