First Ever: NAD's Dolby C Cassette Deck

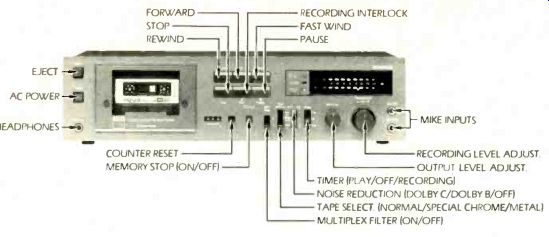

--- NAD Model 6150C cassette deck, in metal case. Dimensions: 16 by 3 1/2

inches (front panel), 9 inches deep plus clearance for controls and connections.

Price: $460; optional RC-61 remote control, $50. Warranty: "limited," two

years parts and labor. Manufacturer: made in Japan for NAD (U.S.A.), Inc.,

675 Canton St., Norwood, Mass. 02062.

Well, folks, Dolby C really is here, with its touted extra noise reduction (some 10 dB more than Dolby B) and improved high-frequency headroom. And it looks like a winner to us-thanks, in part, to the NAD deck in which, as far as we know, it reaches the market for the first time anywhere in the world. Naturally, our curiosity about the newest Dolby circuit had been running high; when we were offered test samples from the first production run, we were delighted, to say the least. And the delight doesn't stop there.

The deck itself doesn't look like a world-shaker on first encounter. Its modest proportions and quiet styling are in keeping with the moderate price and the two-head format. Only the noise-reduction options--DOLBY C, DOLBY B, and OFF--give it away. In practice, as well as theory, the C encoder adds more upward compression than Dolby B and extends farther down in frequency, thus suppressing more noise in both dimensions. At the same time, it introduces less compression at the very top of the range to prevent any exaggeration of saturation effects. Dolby B does, indeed, magnify them; that's why high-frequency response is not quite as good with the noise-reduction switch on in most decks and why Dolby Laboratories came up with the HX circuit. Dolby B tends to exaggerate any response anomaly within its working range because it expands dynamic values in decoding. Since the expansion is even greater in Dolby C, the exaggeration tends to be greater as well, putting an added premium on correct tape matching so that response is inherently as flat as possible.

One of the first things we looked at in the 6150C was its tape matching. As you can see from the response curves, it's very good, especially for a two-head deck, when measured with the Maxell tapes suggested by NAD: UDXL-II as the Type 2 ferri-cobalt, UD as the Type 1 ferric, and MX as the Type 4 metal. Not only is the response quite flat, but the introduction of Dolby B (see the Type 2 record/play curves) does little to un-flatten it, confirming good sensitivity adjustment.

The Dolby C curves (which have their own graph) are not quite as flat as the B curves, but they're at least as good as those for many decks in this respect. Note that the Type 2 curves lose a little at the top end when the Dolby B is turned on and regain it when the switch is moved to Dolby C. The metal tape, with its greater high-frequency headroom, shows no saturation effects at the test level (-20 dB) and therefore no real difference among the three noise-reduction options.

As usual, Diversified Science Laboratories also ran some Type 2 response curves at higher levels to investigate saturation effects. With the Dolby B circuit engaged, there is the usual small loss, which is easiest to document in terms of the frequencies at which the response curves are 3 dB below their reference levels. For Dolby B, they are 5 kHz for the 0-dB curve and 9.5 kHz for-10 dB; without noise reduction, they are 5.5 and 10.5 kHz, respectively; with Dolby C they are 7.25 and 1 L5 kHz-a significant improvement.

The measurements seem to indicate (incorrectly) that a tradeoff is involved: a gain of less than 5 dB in S/N ratio when you switch from B to C, rather than the promised extra 10 dB. Our measurements are A-weighted. Given fairly even spectral distribution of the noise, A weighting usually correlates well with audible effects, but this noise is not evenly distributed. When DSL ran no-signal noise-spectrum analyses with the three tapes, all showed the typical tape noise "response," rising with frequency, without noise reduction. The B circuit takes a healthy bite out of the hiss, delivering its 10 dB of improvement in the range between 2 and 7 kHz and more or less flattening the curves except at the very top end. The Dolby C spectra cut noise by well over 10 dB more across a broad range from the midbass up into the treble-right where it's most needed once Dolby B has taken its bite-but actually reduce noise less than Dolby B as frequency nears 20 kHz. The result is a series of deeply swaybacked curves that average about the same as Dolby B's below 100 Hz and above 10 kHz. The weighting technique, in taking undue account of these maxima, underestimates the subjective importance of the deep valley between them.

Not so, the ear: With any reasonable level setting, Dolby C is dead quiet on the NAD deck. We were able to copy Dolby B open reels with no discernible loss, for example, which no combination of built-in noise reduction, super-tape, and high speed has ever permitted on any cassette deck we've tested before. The effect is astonishing if you're used to that whisper of hiss, always there in the background, when you're listening to cassettes.

Conclusion: As predicted, the Dolby C system effectively addresses itself to both the noise spectra of cassette tapes and the ear's sensitivity spectrum for optimum effect.

Distortion figures proved good, but somewhat surprising. Ordinarily we show only the third harmonic-normally the worst, in tape equipment-in our graphs. Had we done so here, you would have seen figures of 0.48% with Type 2, 0.29% with Type 4, and 0.35% with Type 1 as the maximum measurements (between 50 Hz and 5 kHz), each representing the usual distortion rise at the higher frequencies. Here, however, the second harmonics at the low end of the range were higher than the third at those frequencies: 0.57% with Type 2, 0.46% with Type 4, and 0.71% with Type 1. Maximum THD figures still are below 3/4% for all tapes, so there is no cause for complaint; but showing only the third harmonic would, in this case, have made distortion seem even lower than it is.

If we have any complaint with basic performance, it is that wow and flutter are not quite as low as we have come to expect at this price, though for general purposes, the figures are adequate. We also find that the tape doesn't get up to speed instantly when you release the PAUSE, producing a brief groan in playback or an obvious "chill" if you begin recording during a sustained tone. But it is very quiet and will make edits that are, at worst, barely detectable where background noise is either low or (as in applause) composed primarily of transients.

The meter also elicited some complaint for its rather coarse (2-dB) calibration gradations in the 0-dB range, but since it isn't required for tape matching, this consideration is not as crucial as it might be.

There is provision for tape matching, however. On the back pane) is a horizontal bias slider with a detented center position, the "standard" setting used for all the lab measurements. If you have the necessary test equipment and experience, you could use it to tailor the deck to formulations other than those substantially interchangeable with the recommended Maxell tapes. Since this is a two-head deck, requiring cut-and-try tactics, it isn't easy. That's why the control is hidden; it is not intended for regular use by the owner.

And tape matching obviously is exceptionally important with Dolby C, as it is with any noise-reduction system that introduces more than minimal playback expansion. Since the expansion exaggerates level anomalies (dropouts, poor head contact) as well as response irregularities, it puts a premium on transport quality as well. Though we won't be surprised if a race develops for the least expensive Dolby C deck on the market, coupling it with an inferior design would be both a pity and a mistake. The NAD deck is by no means inferior and therefore contributes materially to the very high marks we give Dolby C in this first encounter. We expect to be hearing a lot more of both.

A Quick Guide to Tape Types

Our classifications. Types 0 through 4, are based largely on those embodied in the measurement standards now in the process of ratification by the International Electrotechnical Commission The higher the type number, the higher the tape price generally is in any given brand.

Similarly, the higher type numbers imply superior performance, though-depending in part on the deck in which the tape is used-they do not guarantee it.

Type 0 tapes represent "ground zero' in that they follow the original Philips-based DIN spec. They are ferric tapes, called LN (low-noise) by some manufacturers, requiring minimum (nominal 100%) bias and the original, "standard" t 20-microsecond playback equalization.

Though they include the "garden variety" formulations, the best are capable of excellent performance at moderate cost in decks that are well matched to them.

Type 1 (IEC Type I) tapes are ferries requiring the same 120-microsecond playback Ea but somewhat higher bias. They sometimes are styled LH (low-noise, high output) formulations or "premium ferries."

Type 2 (IEC Type I) tapes are intended for use with 70-microsecond playback EQ and higher recording bias Still (nominal 150%). The first formulations of this sort used chromium dioxide; today they also include chrome compatible coatings Such as the ferricobalts.

Type 3 (IEC Type III) tapes are dual-layered ferrichromes, implying the 70-microsecond ("chrome") playback EQ. Approaches to their biasing and recording EC) vary somewhat from one deck manufacturer to another.

Type 4 (IEC Type IV) are the metal-particle, or "alloy" tapes, requiring the highest bias of all and retaining the 70-microsecond EQ of Type 2.

------

Preparation supervised by Robert Long, Peter Dobbin, Michael Riggs, and Edward J. Foster. Laboratory data (unless otherwise noted) supplied by Diversified Science Laboratories.

Report Policy: Equipment reports are based on laboratory measurements and controlled listening tests. Unless otherwise noted, test data and measurements are obtained by Diversified Science Laboratories. The choice of equipment to be tested rests with the editors of HIGH FIDELITY. Samples normally are supplied on loan from the manufacturer. Manufacturers are not permitted to read reports in advance of publication, and no report, or portion thereof, may be reproduced for any purpose or in any form without written permission of the publisher. All reports should be construed as applying to the specific samples tested; HIGH FIDELITY and Diversified Science Laboratories assume no responsibility for product performance or quality.

------

(High Fidelity, USA print magazine)

Also see: The Critics Go Speaker Shopping [June 1981]