Key facts you should know before buying a phono cartridge--the smallest, yet most important link in your stereo system.

by Michael Riggs

THOUGH IT'S THE smallest component in your stereo system, the phonograph cartridge influences the sound you get far more than your receiver or amplifier does, regardless of price, power, or sophistication. The source of this apparent paradox is not hard to find. Like loud speakers, phono pickups are electro mechanical transducers, and it is the mechanical element of these devices that gives rise to most of the difficulties.

That music can be retrieved at all from a microgroove LP (much less in stereo high fidelity) is little short of miraculous. The signal on a disc consists of tiny, fragile undulations in an elastic substance called polyvinyl chloride (PVC). These undulations must be accurately traced by an equally diminutive diamond, ground and polished to a precise size and shape and mounted at the end of a relatively long, slender tube or bar, called the cantilever. The cantilever is held in place and supported by an elastomer bearing, which also provides mechanical damping. The size, shape, and alignment of the diamond tip, the mass and rigidity of the cantilever, and the properties of the suspension bearing do much to determine a pickup's frequency response and tracking ability.

Though important, the task of a cartridge's electrical system is relatively easy: It must translate the motion of the stylus cantilever into a corresponding electrical signal for each stereo channel to be passed through the tonearm wiring to the phono inputs of an amplifier or receiver. Exactly how this is achieved varies from model to model, but almost all modern high fidelity pickups are magnetic designs (as opposed to, for example, the piezoelectric transducers traditionally used in inexpensive compact systems). In one way or another, all of these depend on the relative motion be tween a magnetic field and a set of coils.

No one type of magnetic pickup has any magic advantage over the others; good cartridges come in all flavors moving-coil, moving-magnet, and moving-iron. There are practical considerations that might tilt a buying (or design) decision one way or another, however.

For example, most moving-coil designs have very low output, necessitating the use of a step-up transformer or a so called head amp to boost the signal to a level high enough to drive a standard phono input. The reason for their low output is simple: Since the coils are attached to the aft end of the cantilever, they must be extremely small and light weight, so fewer turns of wire can be employed and the output is reduced correspondingly. Adding more coil raises the mass of the moving assembly. The greater the mass, the greater the force required to accelerate it to a given velocity.

So, if the effective mass of the stylus assembly goes up, so must the tracking force, or else high-frequency tracking ability will be reduced. Increasing the coil mass also tends to reduce the stylus assembly's resonance frequency--bringing it within the audible range and creating a "peaky high end" unless the de signer is careful. In fact, this tends to be something of a problem even with conventional low-output moving-coil cartridges, which often have rising high ends and almost invariably have relatively low compliance and high tracking force requirements.

Fixed-coil (moving-magnet or moving-iron) cartridges have a small, powerful magnet or a small piece of iron attached to the end of the cantilever, making these problems more amenable to a simple, inexpensive solution. Be cause the coils are not part of the moving system, they can be made large enough to provide fairly hefty output-usually in the vicinity of 1 millivolt for a groove velocity of 1 centimeter per second. And their relatively high inductance (an innate property of coils, and proportional to the number of turns of wire in the coil, among other things) in combination with the input impedance of a phono preamp forms an electrical low-pass filter that rolls off at high frequencies. Designers of fixed-coil cartridges exploit this characteristic to compensate for the high-frequency mechanical resonance peak and achieve flat overall frequency response while maintaining high compliance and good high-frequency tracking ability.

Cartridge Loading

Obviously, there must be at least one fly in the ointment, or no one would make anything but high-inductance fixed-coil magnetic pickups. Indeed.

there are a couple. One is that, all else remaining equal. the higher a cartridge's coil impedance (i.e., resistance and inductance), the more noise is generated.

But given the signal-to-noise ratio of records, this is more a theoretical disadvantage than a practical one. More serious is the matter of load sensitivity. Since, as we've seen, fixed-coil pickups may be designed to work with a specific preamp input load, get ting that load may he important to their frequency response. Standard loading calls for a resistance of 47,000 ohms (supplied by the phono input) in parallel with some capacitance (provided by the phono input together with the tonearm wiring and cables), whose value depends on the specific cartridge model. For that reason, it is important to make sure be fore you buy a cartridge that is compatible with the capacitance it will find in your system. Deviations of ± 50 picofarads usually are acceptable, and if the error is on the low side, you can always bring it back up to the desired value. It is usually impractical, however, to remove capacitance, so if your system has too much for a certain cartridge, you probably should choose a more compatible model. Moving-coil and a very few low-inductance fixed-coil cartridges-along with the Micro-Acoustics pickups. which are not magnetic and therefore do not have coils at all-are insensitive to capacitive loading, so there's no need to worry if you select one of them.

The Key Specifications

But loading is only part of the story: A cartridge must be capable of producing flat frequency response when optimally terminated. or else there is little point in making the effort. You might reasonably expect a good modern pickup to he flat within ± 1 1/2 dB from 30 Hz to 15 kHz. That envelope is wide enough to permit significant audible differences between cartridges but about the best you can hope for, given the cur rent state of the art and the fact that different manufacturers judge their results by different test records, which are them selves in various ways and to various degrees less than perfectly flat in response.

It is also worth remembering that cartridges are to some extent temperature-sensitive. Usually they boost treble at high temperatures and roll off the highs to some extent (and possibly impair tracking) at low temperatures. In most homes, these effects will not be dramatic. but do not be surprised if your system sounds a little "hot" in midsummer or a little dull and fuzzy in the winter.

Another important desideratum is a cartridge's ability to keep the two stereo channels adequately separated. Fortunately, about 20 dB of separation at mid-band (around 1 kHz) is all that is necessary, and there probably isn't even one cartridge on the market today with pre tensions to high fidelity that doesn't do at least that well.

------------------

How to Spot Tonearm Resonance Problems

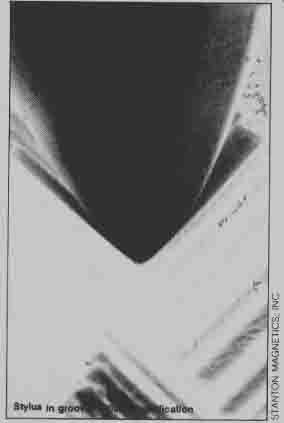

Most records have many tiny warps concentrated below 8 Hz. If the center frequency of the arm/cartridge resonance furls there, response to these warps will he exaggerated, causing increased distortion, "warp wow," impaired tracking, and possible overload of the tape deck or amplifier. To this problem, view the stylus from the side as it traces a reasonably flat record: if it hobs up and down relative to the cartridge body (see above), the resonance frequency is too low.

--------------

Perhaps the most important pickup performance characteristic is tracking ability. The stylus must remain in intimate contact with the groove walls at all times, through the highest recorded velocities and accelerations. At best, mis tracking will cause the sound to lose some of its smoothness and detail: at worst, it will throw the stylus clear out of the groove. And any time there is mis tracking, there will be irreversible record damage. (One of the morals of this is that it's better to set a cartridge near the top of the manufacturer's recommended tracking-force range than to skimp when you adjust the VTF.) Sadly, there is no standard method of specifying tracking ability, making comparisons difficult.

HIGH FIDELITY'S test reports show it at 300 Hz. in dB above RIAA reference standard level (higher numbers being better), and comment on any difficulties encountered during listening tests.

Mating Arm to Cartridge

As with frequency response, tracking ability is not solely a function of the cartridge design: The tonearm also has its say. Because the mass of the arm is supported by the stylus through a compliant (i.e., springy) cantilever-suspension bearing, there is some low frequency at which the arm/cartridge system will resonate. At that point, there will be a peak in the frequency response (which may, in turn, cause phono preamp overload, wasted power, and/or excessive woofer motion) and markedly reduced tracking ability.

Consequently, it is desirable to keep the amplitude of this resonance as small as possible and its center frequency in a range where signals are both rare and weak. Which is to say, it should be well damped and should occur below the audible range and above that in which it will exaggerate record warps-between about 8 and 12 Hz. (Reducing pickup compliance or physical weight or the effective mass of the tonearm tends to raise the resonance frequency; increasing any of these tends to lower the resonance frequency.) High resonance frequency is fairly rare these days, but it does sometimes occur when a low-compliance moving-coil cartridge is used with a low-mass tonearm designed with the more common high-compliance cartridges in mind. It usually appears in the form of exaggerated bass response and poor tracking of strong bass passages. But it can be corrected simply by adding mass to the tonearm.

The more difficult (and, unfortunately, far more common) situation puts the resonance frequency too low. The most direct evidence of this is relative vertical motion between the tonearm headshell and the surface of an apparently flat record. Viewed from the side at eye level, the entire cartridge/tonearm assembly should remain stable, with no bobbing of the headshell and pickup body relative to the record and stylus. If you see it bouncing up and down on a flat disc, the resonance is badly placed and underdamped. Remedies include substituting a cartridge of lower mass or compliance or a tonearm of lower effective mass, or introducing damping.

You can get some idea of which way to jump by looking at HIGH FIDELITY'S turntable and cartridge reports. For the former, we show vertical and lateral resonance with a Shure V-15 Type III cartridge, whose weight and compliance are typical of most models now on the market; for the latter, the resonance figures are obtained with an SME 3009 Series II Improved tonearm, which has an effective mass of approximately 8 grams, in the low end of the range of effective masses available in modern arms.

Distortion

Not surprisingly, mistracking or severe resonance problems will generate audible distortion, as will serious angular misalignment (lateral. vertical, or otherwise, of more than a few degrees) of the stylus relative to the groove. Otherwise, you shouldn't hear anything amiss, notwithstanding the grossness of cartridge distortion figures compared to those for, say, amplifiers. You should hear in mind, however, that while capable of better overall performance, modern line-contact styli are more critical of imprecise alignment than spherical or even elliptical styli.

When everything is done right, to day's best cartridges are capable of astonishing performance. And. to the great good fortune of the budget-conscious, most manufacturers make second-best cartridges nearly as good as their top-of-the-line models. As in the past, we will see evolutionary improvements in the technology as manufacturers continue to chip away at the problems attending the reproduction of analog discs, until the final quantum jump is made into the new world of fully digital audio.

(High Fidelity, Jul. 1981)

Also see:

A Pro's Approach to Audio Accessories

Link | --Harman Kardon 680i AM /FM receiver (review, Jul. 1981)

Link |