Auto Reverse Teac Cassette Deck with DBX

Teac V-95RX bidirectional cassette deck, with Dolby B and DBX noise reduction.

Dimensions: 17 1/4 by 4 Inches (front panel). 10 1/2 inches deep plus clearance for controls and connections. Price: 5625, optional RC-95 remote control, $60. Warranty: limited.--one year parts and labor. Manufacturer. Teac Corp., Japan: U.S. distributor: Teac Corp. of America. 7733 Telegraph Rd., Montebello. Calif. 90640.

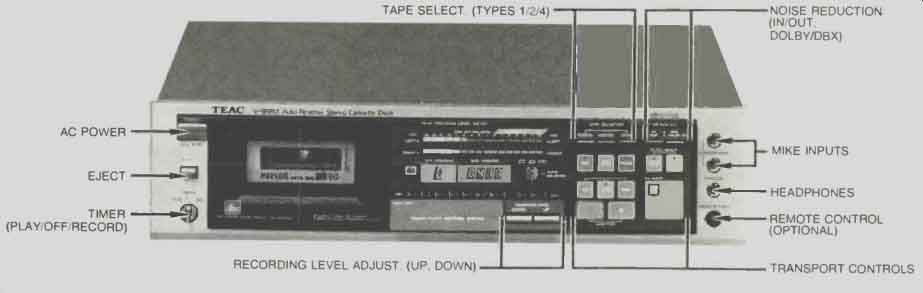

SOME TRADITIONAL HALLMARKS, as well as some new departures, are embodied in the Teac V-95RX. Teac was, for example, the first tape-deck manufacturer to offer DBX noise reduction (at that time well established with professionals, but still relatively esoteric in consumer equipment). And it has long made tape equipment capable of recording (as well as playback) in both directions of tape travel. Newer are the smooth, flexible control panel, which is fast becoming a fixture on Teac cassette decks, and two elements we have seldom seen before: a powered fader system and some relatively elaborate playback programming, both of which contribute significantly to this deck's appeal.

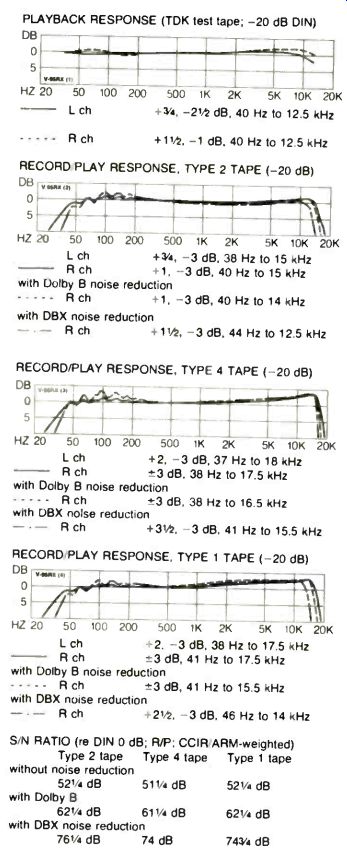

------------All data shown are for the forward direction. Data measured

for the reverse direction are not significantly different from those

for the forward direction.

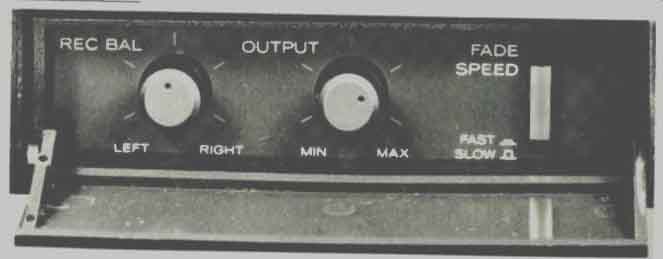

-------------A flip-down door on the Teac's front panel conceals a

recording-balance control, an output-level control, and a two-position

fader-speed switch for the motorized pushbutton recording-level controls.

Automatic reverse is triggered by an infrared sensor that can distinguish between recording tape and leader-and thus make the reverse almost instantaneous. Teac claims 150 milliseconds on the turnaround time, and we wouldn't argue the point.

That's about as large a "hole" in musical continuity as you're ever likely to get from a dropout: an annoyance if it falls in the middle of a sustained cantilena, but conceivably capable of going unnoticed in some material. Thus, even if you leave the reversing entirely to the automatic mechanism in both recording and playback, there will be less interruption (and less loss of program) than with any but a very few other automatic-reverse decks. And if you want even less obtrusive direction changes, you can trigger the reverse manually when you record and apply adhesive foil strips to the tape to make playback reverses automatic from that point, rather than from the end of the tape.

The usual three options apply: unidirectional operation (permitting playback or recording in either direction, but with no automatic change of direction), out-and-back bi-directionality (with automatic re verse at the end of the first side only), and continuous repeat (inoperative in recording, but playing both sides of the cassette until you rescind the order). These options combine in various ways with both the programmed start and stop options (which Teac calls "block repeat") and what Teac calls CPS, for Computomatic Program System. The manual, which is much better than average for a cassette deck, lists all the permutations-which seem obvious once you're familiar with the deck, anyway-so we'll content ourselves with an overview here.

When you know you will want to return to your current position on the tape, you press START MEMO; at the end of the passage of interest, you press STOP MEMO.

The block repeat now is programmed to repeat the passage (which may go from Side I to Side 2 under some conditions) until you stop it. This replaces the memory-rewind functions of most decks. (There is no zero-reset button for the counter, though it will reset if you press EJECT.) The CPS feature provides random access of any one selection. With the deck set for the continuous repeat mode, in either direction of play, you press the CPS button and then either of the fast-wind buttons.

Each press of the latter increases by one the number displayed in the "CPS program" window, which tells you how many inter selection blanks the transport will pass over before cueing up and beginning playback at the next. The number can be as high as 15 (if you step it too high, you can back off by pressing the fast-wind button for the opposite direction, which subtracts from the total shown); if the search takes the tape to the end, the transport reverses direction and continues its countdown on the other side.

Naturally, there is a RECORDING MUTE to provide the CPS with appropriate inter selection blanks. When you tap it, it's programmed to lay down four seconds of silence before switching the V-95RX into RECORDING/PAUSE. If you want a longer blank, you can keep your finger on the button; whenever you release it, the deck will go into RECORDING/PAUSE. And the big STOP button at the lower right of the trans port-control group, which acts like a normal STOP, contains a small separate button with in it that releases all programming functions. (The small control is a true pushbutton, rather than a push area such as the ones in the flexible control panel that make up the transport control complex both here and on the optional remote control.) If you want to release either of the block-repeat "cues" or the CPS function without interfering with the others, a second press of the button for that function will do so-and will extinguish an LED to let you know that it has been released.

------------

A Quick Guide to Tape Types

Our tape classifications, Type 0 through 4, are based primarily on the International Electrotechnical Commission measurement standards.

Type 0 tapes represent "ground zero" in that they follow the original Philips-based DIN spec. They are ferric tapes, called LN (low-noise) by some manufacturers, requiring minimum (nominal 100%) bias and the original, "standard" 120-microsecond playback equalization.

Though they include the "garden variety" formulations, the best are capable of excellent performance at moderate cost in decks that are well matched to them.

Type 1 (IEC Type I) tapes are ferrics requiring the same 120-microsecond playback EO but somewhat higher bias. They sometimes are styled LH (low-noise, high-output) formulations or "premium ferrics." Type 2 (IEC Type II) tapes are intended for use with 70-microsecond playback EC) and higher recording bias still (nominal 150%). The first formulations of this sort used chromium dioxide; today they also include chrome-compatible coatings such as the ferricobalts.

Type 3 (IEC Type III) tapes are dual-layered ferrichromes, implying the 70-microsecond ("chrome") play back EO. Approaches to their biasing and recording EQ vary somewhat from one deck manufacturer to another.

Type 4 (IEC Type IV) are the metal-particle, or "alloy" tapes, requiring the highest bias of all and retaining the 70-microsecond EQ of Type 2.

--------- Even more striking is the motorized recording-level fader. At rust we thought it a bit gimmicky, but use quickly altered that assessment to admiration. At the bottom center of the front panel is a little flip-down door behind which lurk an output level control, a recording-level balance control, and a two-position fader-speed switch. The fader itself is a pair of buttons (UP and Down) just to the right of the door. A horizontal, illuminated scale, calibrated from 0 to 10 and located just above the door, tells you where the recording level is set. The slow drive speed takes about ten seconds to cover the entire scale, while the high speed makes it in about half the time-very nice for gradual or snappy fades, respectively, at typical fader settings.

The peak-reading level indicators are calibrated from- 30 to +10 dB, in 1-dB steps between-3 and +3 and 2-dB steps extending to-7 and +7. As the data from Diversified Science Laboratories show, the rise time is very quick and the decay time long enough to allow easy evaluation. The "bar graph" actually shrinks back to the left, for all maxima below the 0-dB indication, once the signal is removed. This pro cess begins after about one second, but it takes twice that long before the bar has shrunk by 20 dB to the IHF/EIA indicator-decay rating point. When the signal reaches "into the red" (to above 0 dB), the highest cursor stays lit for about two seconds, pro viding a peak-hold action in this range. The absolute calibration of the 0-dB indication varies slightly depending on the setting of the tape selector: 1 dB more sensitive than DIN 0 for Type 2 or Type 4 tape, I dB less sensitive for Type 1. Further, the indicators are marked to show that maximum readings for "normal" (Type I) tapes should be between 0 and +2, for "Co" (Type 2) at +3, and metal (Type 4) at +3 to +5. The top of the scale is reserved for DBX noise reduction, which presents a special case because of its downward compression of high-level signals, so that a signal level of, say, +8 dB goes on the tape at a lower level than it would with Dolby B or with no noise reduction.

At Teac's suggestion, DSL used TDK SA as the basic Type 2 tape and MA as the Type 4-both with excellent results for a deck with no bias adjustment or multiplex-filter defeat and with a single four-gap, combination record/play head. The company declined to specify a ferric (Type I) tape, however, though several formulations are listed in the manual. The lab chose TDK AD, which produced excellent results, though a tape of somewhat lower sensitivity presumably would have flattened out the shelving in the Dolby B curve.

In the listening room, we found we could get best results with the Type 2 group (chromes/ferricobalts) and Type 4 (metals), which tend to be more standardized than Type 1 (ferric) tapes (and therefore less variable in their bias, EQ, and sensitivity requirements). Quietest results are, of course, with the DBX noise reduction. It should be used with care, because it is at its best when signal levels are kept high (short of compression or distortion), but the calibration of the V-95RX's level indicators helps ensure optimum settings.

Every one of the V-95RX's many features seems chosen with the home

music enthusiast in mind. Many times, when we question a manufacturer

about why a certain feature is included in a given model, the answer

comes back, "Because it was on the chip." Teac, to its credit,

has not let technological grandstanding supplant thoughtful design.

------

(High Fidelity, Jan. 1983)

Also see:

Teac Z-7000 Cassette Deck (AUDIO mag, May 1984)

Technics SU-V9 Integrated amplifier (Equip. Report, Jan 1983)