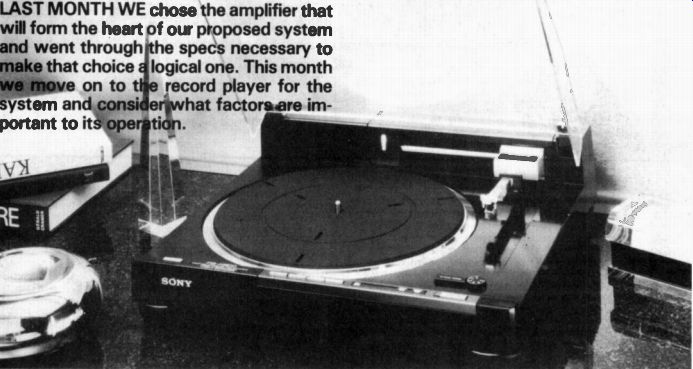

LAST MONTH ,WE chose the amplifier that will form the heart of our proposed system and went through the specs necessary to make that choice a logical one. This month we move on to tile record player for the system and consider what factors are important to its operation.

FROM A SYSTEM POINT OF VIEW the record source and the amplifier must be chosen to compliment each other electrically. The player has to provide the correct level of signal, from the cartridge, to match the amplifier input and it must have the correct balance to suit your tastes and produce a smooth overall result from the system as a whole.

Follow the guidelines and keep in mind possible upgrades; changing the cartridge is often the first of these. Make sure, therefore, that the arm will accommodate any future ambitions you may harbor. If you're quite sure that you have none, an integrated player (combining turntable and arm) will probably suffice, but for those with aspirations to higher-fi, separates are the most economical course in the long run.

The basic aim of a record playing system is identical whether it is an integrated arm/cartridge/deck bought complete, or is assembled from separate components. Whatever the method, the end result is that of extracting as much of the mechanical in formation from the LP as possible and converting it into an electrical signal which can, after amplification, induce the loudspeaker to re-create the original sound.

For this process three things are necessary: a turntable to rotate the LP at the correct speed, a signal producer (cartridge( to track, or follow, the recording groove and a means of holding that cartridge in exactly the right position above the record to enable it to do this accurately--the pickup arm.

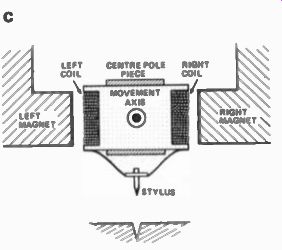

The cartridge is the transducer, the device which converts one form of energy into another; it takes the vibrations from the stylus and produces an electrical output corresponding to that vibration. Figure 1 illustrates the method of operation.

Getting Turned

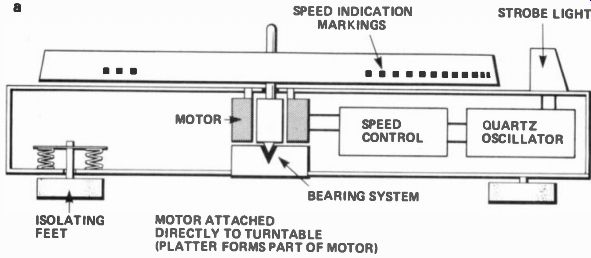

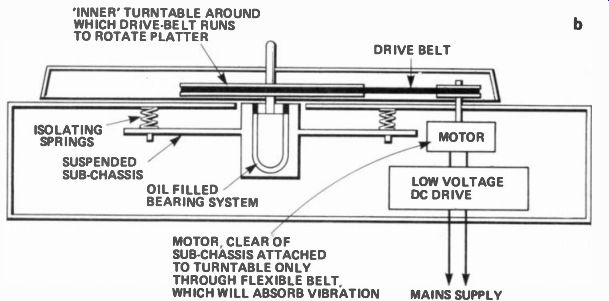

There are two main types of turntable on the market; direct-drive and belt-drive (Fig. 2), as well as two kinds of pickup arm (Fig. 3) and two leading cartridge varieties (Fig. 4). Thus it is better to ignore the myriad 'one-offs' such as moving iron cartridges and idler-drive turntables. As we are concerned here with choosing and using a first system, I think this is permissible.

To a large extent the operating method is irrelevant, much as it was with amplifiers, but because the disc-player is a considerably less refined product than the amp, differences between units is considerably more marked. Moving coil cartridges offer--in general--a more detailed and 'open' sounding result but at the cost of less secure tracking and looser bass (at the low end of the market, anyway). As with most things, differences become less general as the price goes up! Moving coils are more expensive to make superbly but the best is something truly wonderful! At up to around £100 ($150, 1982) a unit, it remains totally a matter of taste as to which type you will prefer.

If you read some of the hi-fi mags every month you will get the decided impression that there exists only one unit worthy of turning records around under a cartridge, but there are literally dozens of useful turntables available--all of which do the job very well indeed. Naturally some do it better than others, but cost and value for money vary enormously.

First Off

You'll probably be well advised to stick to an integrated deck at the beginning. A separate deck with added arm and cartridge can offer performance advantage, but will require setting up both initially and later on. If this thought induces spasms of panic--or even a moment's indecision--either find a friendly dealer or forget it for now. There is always time later, when upgrading--after building up some 'hands-on' experience.

So to specs and interpreting them. We'll take it one component at a time so that the information can be applied equally to both the integrated deck and to separates. As with amplifiers, if we haven't mentioned it below, it's irrelevant to sound quality and can be ignored! Turntables Quartz-locked: Direct-drive turntables need some form of speed stabilization and early models compared the rotation with the ultra-stable mains frequency of 50 Hz to judge how accurately the unit was maintaining its speed. Later designs nearly all employ a crystal oscillator, like those used in watches for ex ample, at around 2 MHz. This ensures a much higher degree of accuracy.

Another advantage of this system is the provision of 'variable speed' or Pitch Control where the nominal 33 1/3 RPM can be varied by a set percentage to allow correction of recording faults.

Fig. 1a The mechanical relationship between the pole pieces , the magnet

and the record groove wall.

Fig. 1b Axis A can be referred to Fig. la to show the positioning of the generator within a moving magnet cartridge.

Fig. 1c. Moving coil basics. As the stylus moves the coils, a current is generated within them by the magnetic field from the fixed magnets.

Wow and Flutter: As the turntable's main job is to rotate the LP at the correct velocity, any variations from that velocity can be considered as a form of distortion--it will render impossible the accurate replay of the source material on the record. There are two types of speed variation; (i) a sort of slow oscillation back and forth about the nominal value--noticeable on piano music in particular (wow); (ii) a short term variation, very rapid in nature (flutter) the speed of which can vary downward from a very fast unsettling waver in musical notes. Both are well under control in modern designs and figures of less than 0.5% are easily achieved. The best direct-drive designs can notch up less than 0.05%. Look for anything under 0.2 %. Rumble: A common feature of all turntable types is the bearing on which the platter (or record support) rests. Any sort of mechanical rotating system will vibrate to some degree or other and a turntable bearing is no exception. As the stylus is picking up mechanical information from the record, if the latter is vibrating unduly due to the bearing, this will be passed on to the amplifier and appear from the loudspeakers as a very low frequency growl--rumble.

Usually specified as a signal-to-noise ratio in decibels (dB), rumble should be only a minor problem on new units--but watch out for it on second-hand components! Look for figures over -45 dB unweighted, or -65 dB weighted.

Platter Mass: Simply the weight of the turntable upon which the record rests! More important on belt-drive units, where the mass is used like a flywheel to iron out minor variations in speed with sheer inertia. The best belt-drive units use somewhere around 6 lbs upwards. More important than actual weight is that the platter offers proper support to the LP. Mistrust any turntable mat that is not totally flat!

Damping/Insulation: It is obviously important to isolate the turn table from all outside vibration as much as possible in order that only the record groove causes the stylus to move. With direct-drive decks, where the motor is fixed to the plinth, this is more important than with the better belt-drive units, where the entire drive systems 'float' on isolating springs.

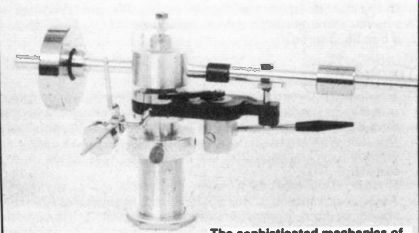

-- The sophisticated mechanics of a modern tone-arm.

Fig. 2a. Schematic representation of a direct drive turntable. The 'dots'

around the rim of the platter provide a visual check, by strobe-light,

of the speed.

Fig. 2b. Schematic of a belt drive turntable--'older', but still capable

of exceptional performance if correctly set up.

Pickup Arms

Effective Mass: This is the mass that the stylus will have to pull behind it when following the record groove. This parameter is particularly important in matching the arm and cartridge. Cartridges with a high compliance (a large degree of flexibility) are best matched to arms with a low effective mass. However, some of the modern (particularly moving-coil) units have a low compliance and will give of their best in medium to high mass arms. This is because the arm and cartridge together form a mechanical 'tuned circuit' which will behave in much the same way as a capacitor-inductor electrical circuit does and will exhibit a resonant frequency--a particular frequency at which it is easier to move than any other. Thus the frequency response will not be linear but will show a preference for this resonant frequency. The range of resonant frequencies for most arm/cartridge assemblies lies between 5 Hz and 25 Hz.

In order that audible frequencies are effected as little as possible, it is advisable to choose components which have a combined resonance below 20 Hz, but above 75 Hz, the frequency around which record warps usually occur. Table One gives you a range of effective masses and cartridge compliances and lists their resonant frequencies. Choose the arm/cartridge in your system to have a resonant frequency of between 10 Hz and 15 Hz and all will be well.

Bearing Friction: Usually quoted in two forms; lateral and vertical.

As most pickup arms rely on two sets of bearings, one aligned in the same direction as the record surface and the other perpendicular to it, both figures are important. They tell you the amount of 'drag' imposed by the arm when the cartridge tries to move it! Figures should be given in milligrams and are quoted as the force required to move the arm in a given direction (laterally across the record or vertical to it) when applied to the stylus. Look for something under 30 mg as good and don't use cartridges with a compliance of over 25 mg in an arm with any more than 30 mg friction! Tracking (or Downforce) Range: Tells you what range of tracking weight can be applied to a cartridge fitted into the arm.

Sounds simple enough, but also watch out that the actual weight of the cartridge you buy can be accommodated by the arm. Somewhere in the spec there will be a 'maximum weight' figure for matching cartridges. It is unwise to come close to this as your available tracking force will be limited.

Bias Compensation:

Every arm should have some! Any object moving in a circle feels a force acting on it, trying to throw it away from the centre of the circle and a pickup cartridge is no exception. As the job of the arm is to keep the cartridge free of outside influences, by definition, it must counter this force. All a bias compensator does--usually with a hanging weight--is to pull the arm in the opposite direction to the force, theoretically by an exactly equal and opposite amount; this is determined by experimenting with a test disc. As long as the arm has a bias compensator--don't worry about it! Some integrated decks use springs or magnetic plates and possess a dial to add or subtract bias while the cartridge is playing a record. Nice, but unnecessary.

Lead Capacitance: Exactly what it says. The amount of capacitance added to the electrical load imposed upon the cartridge by the wiring from headshell to amplifier. Most cartridges are sensitive to this figure to some degree as the capacitance is like a mild frequency filter and 'rolls-off' the response. Unless you're making an expensive start to your hi fi career by buying a system well up the price scale, it is generally safe to ignore this effect as it is very minor and not liable to effect the music on any but a very few units.

Tracking Error: As nearly all pickup arms are of the type where they pivot at a single point behind the turntable, it will be impossible for them to follow the path taken by the record cutting head used to produce the LP, as this is driven across in a straight line. However, with correct setting-up, the difference in the paths at any point on the record will be small--less than 2° in fact. On integral decks there is little the buyer has to worry about, things will have been worked out for him (hopefully) during manufacture. If you are assembling a deck from components, use the provided protractors--as outlined in our installation article--and all should be well. In reading reviews etc, look for a figure less than ± 2°.

Adjustments: Take all you can get! The ability of a pickup system to operate at maximum efficiency depends upon its mechanical accuracy and alignment. A deck which allows you more freedom to 'tinker' probably also offers more chance to set it up correctly and thus earn a better sound quality!

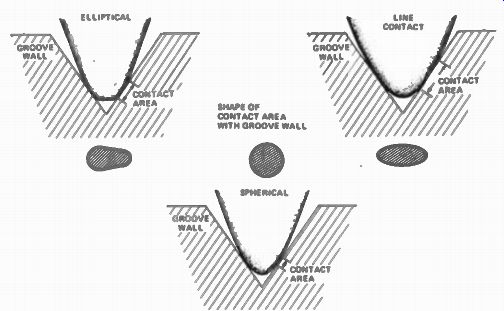

------ The three most common stylus profiles and their relative parameters.

Note that whilst the elliptical offers a greater ability, its area of contact will generate increased record wear.

-------------

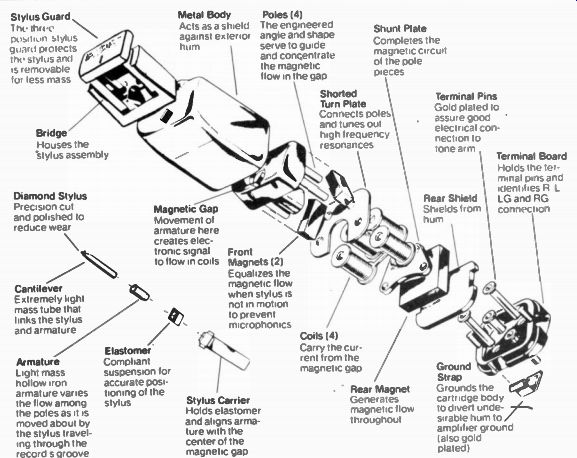

above: This exploded view of an Empire cartridge gives an indication of the lengths that top manufacturers will go to in order to beat resonances and colorations.

Stylus Guard--The three position stylus guard protects the stylus and is removable for less mass

Bridge Houses the 'stylus assembly Diamond Stylus Precision cut and polished to reduce wear

Cantilever--Extremely light mass tube that links the stylus and armature

Armature -- Light mass hollow iron armature varies the flow among the poles as it is moved about by the stylus traveling through the record s groove

Metal Body

Poles (4)

Acts as a shield

The engineered against exterior angle and shape hum is serve to guide and concentrate the magnetic flow in the gap

Magnetic Gap--Movement of armature here creates electronic signal to flow in coils

Elastomer Compliant suspension for accurate positioning of the stylus

Front Magnets (2)

Equalizes the magnetic flow when stylus is not in motion to prevent microphonics

Stylus Carrier

Holds elastomer and aligns armature with the center of the magnetic gap

Shorted Turn Plate

Connects poles and tunes out high frequency resonances

Shunt Plate

Completes the magnetic circuit of the pole pieces

Coils (4)

Carry the current from the magnetic gap

Rear Magnet--Generates magnetic flow throughout

Terminal Pins Gold plated to assure good electrical connection to tone arm

Rear Shield

Shields from hum

Ground Strap--Grounds the cartridge body to divert undesirable hum to amplifier ground is also gold plated)

Terminal Board--Holds the terminal pins and identifies R L LG and RG connection

-----------------

Cartridges

Compliance: A measure of the 'springiness' of the cantilever assembly that holds the stylus, i.e. how easily it bends! This is a good thing as far as following the record groove goes, but a bad thing when it comes to moving the weight of arm and cartridge along behind it. Thus there is no right or wrong value.

High compliance means 'easily bent' and should be used only with low-mass arms. Compliance is measured in 'cu' (compliance units). Anything above 30 cu is high and anything under 15 Cu is low. Shure moving-magnet pickups average 30-40 Cu and the best moving-coils under 10 cu! A high arm mass is anything over 15 grams, with anything less than 10 grams being considered low mass. Read back over the section on effective mass and take a look at Table One, which illustrates the interaction between these two parameters.

Tip-Mass: Is the weight of the actual stylus as seen by the groove walls! This will determine record wear--and how well the stylus can stay in the groove at high frequencies, since there will be a second resonance here somewhere above 15 kHz.

The higher this resonance (lower tip mass) the better, to some degree--suspect any figure less than 20 kHz! Output Level: There is no figure current for how much voltage a cartridge should generate; it will depend on the amp it is to feed. Figures are generally quoted in terms of millivolts output at 5 cm/sec recorded velocity. An average moving-magnet design will develop around 3 mV at 1 kHz and a moving-coil substantially less. Look to match the quoted figure with the amplifier input sensitivity and you won't go far wrong!

Frequency Response: As with amplifiers, a measure of 'flatness' or freedom from uneven treatment of an input. The cartridge should replay any frequencies between 20 Hz-20 kHz at an equal level. The limits (in dB) quoted with the figure--ignore it if there are no limits--show how close the unit comes to meeting this requirement. Look for ± 2 dB maximum across 20 Hz-20 kHz.

Distortion Figure:

As the cartridge is a transducer, it will impart some distortion to the signal during its transformation. Figures generally quoted are for Intermodulation Distortion--how much one note will effect another when replayed simultaneously--and Total Harmonic Distortion, which is the degree to which a pure sine wave going in is less than pure coming out! Look to better 2% on all distortions figures.

Cash Considerations

With an integral deck, assign 30 percent of your budget to the record player and cartridge. As separates will initially be more expensive, assign 35 percent of the total if you choose this option. The extra comes from the speaker allowance, on the grounds that, as you are in the upgrading game anyway, you will wish to improve them later on. The extra cash will make more audible difference at the source, initially.

Arms and the Man

Integrated decks offer the advantage that they require little, if any, setting up. Generally speaking, there is little the user can adjust, except the cartridge alignment in the headshell. If you have decided on such a machine then read carefully through the adverts in the hi-fi press from the larger dealers. Many of them run package deals, at very attractive prices, which comprise either an integrated deck with a good cartridge or even separate turntable/arm/cartridge set-ups, pre-assembled and pre chosen to make things easy! In just about every case, a Far Eastern machine will arrive with a pre-fitted cartridge. Throw it out! (or, at best, save it for a spare). Such offerings are usually of little value compared to the deck itself and are one reason why many dealers offer the aforementioned deals. Choose your own cartridge following the dealer's advice as to compatibility with the selected deck. If in doubt, ring up the manufacturer of the turntable and ask them whether your proposed cartridge is compatible. You'll be surprised at how helpful hi-fi companies can be!

Separate disc-playing components are more trouble to choose, but offer much greater flexibility--and quality--later on. The problem is made irrelevant to some extent by the scarcity of good quality turntables, without an arm, at anything less than a king's ransom. No matter what the advertising may tell you, spending £400 on a turntable in a £600 system is sheer lunacy.

It makes sense only if you're selling turntables! Given the level of other components in the system it would be impossible to distinguish, say, the Oracle at £680 from the TD 160 BC at £110. Keep a sense of proportion.

It is absolutely essential that you hear the cartridge you want together with your proposed loudspeakers. These two components are the ones most likely to possess a strong 'character', or sound of their own.

For example, a number of budget loudspeakers can sound a trifle dull and lifeless, while still being good value for the money.

Partnering these with a bright sounding cartridge can produce an overall result which is pleasing and more accurate.

It doesn't matter which you fix on first, speaker or cartridge, but choose them together. You may, for instance, decide that because space in the home is limited, you need compact enclosures of below a certain size. Once more, make up a shortlist and audition a few with the same cartridge. Then get the cartridge changed. After a few minutes the combination which appeals to you most will become apparent.

Pick Up Pickups

With the advent of the new generation of moving-coil cartridges and their higher outputs, it is feasible to use such a device in a first system. However, don't be tempted to buy a cartridge simply because it is a moving-coil unit. The mode of operation is totally irrelevant; it is the sound that matters and if you prefer some other type of unit, go buy it.

By all means consider specification seriously, especially with regard to matching up units, but don't let one single line of ad copy or formulae decide which hi-fi you buy. Let your ears do the choosing for you! This is especially important when it comes to loudspeakers, as we shall see next month.

-----------------

(adapted from: Hobby Electronics magazine)

Also see:

Link | --Link | --SCALING the Hi-Fi HEIGHTS Part 4

SCALING the HiFi HEIGHTS (Part 1)