How to select components and $$$ allocations for matching performance.

If you are planning to purchase your first stereo high fidelity component system and thumbed through this directory, the awe some number and variety of components de scribed may seem intimidating. As a first time buyer, the options, permutations, and combinations seem endless. Where to be gin? Actually, choosing a well-matched component system is not all that difficult. An informed and experienced audio dealer can guide you toward a sensible approach to component selection, but it helps if you provide him with some basic information. You should have some idea of how much you want to spend for your first set of stereo components. You should also give some thought to possible expansion and upgrading of your system at a later date. Happily, component stereo systems lend themselves to such upgrading and we will deal with that subject after we have outlined the basics of buying your first component system.

WHAT TO BUY

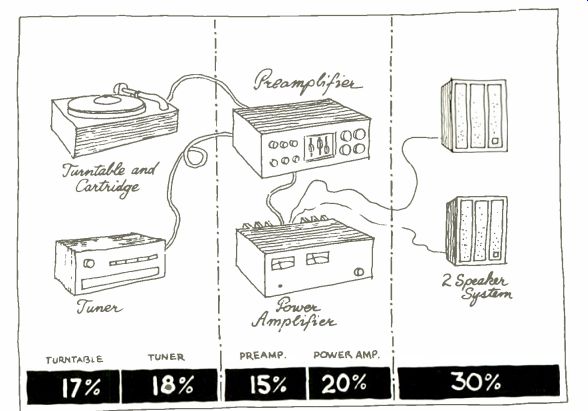

The majority of high fidelity component systems consist of only three or four basic components. You will, of course, need a pair of loudspeaker systems. Most popularly connected to the speakers will be a single electronic component known as a stereo receiver. The receiver really contains three separate sections: (1) a tuner for FM and AM radio broadcasts; (2) a preamplifier/control section to amplify these radio signals, as well as other possible signal sources such as those produced from a record-playing system or a tape deck; and (3) a power amplifier, which further amplifies these signals so they are powerful enough to drive the loud speakers satisfactorily. The receiver can, of course, be replaced by separate components such as a tuner, preamplifier, and amplifier.

This generally results in a higher-priced, though more flexible, system. The savings gained by combining these three components into one physical package are often substantial, and that is why most first-system buyers choose the all-in-one receiver approach.

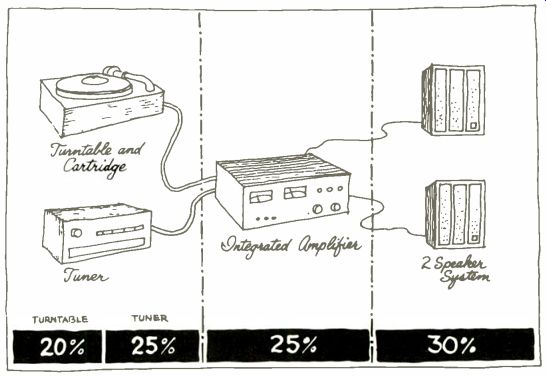

Even in a first, modestly priced system there may be justification for selecting separate components. For example, if you live in an area where there is little or no desirable FM reception, you may want to forego the expense of an FM program source. In that event, it may be more economical or practical to purchase an integrated amplifier (which includes the preamplifier-control and power amplifier sections of a receiver, but omits the tuner section) at the outset.

Choosing this type of component as the electronic heart of your system does not eliminate the possibility of AM or FM as a future program source if you move to an other area, or if FM stations become more plentiful in your listening area. A separate FM or AM-FM tuner can be added to such a system at any time in the future.

The final component combination that should be considered in any basic system is the record-playing system. The two basic elements of this combination are the turn table/tonearm system and the phono cartridge, the latter containing the tiny diamond stylus that rides along in record grooves.

In addition to these basic components, you may want to add a tape deck to your system.

Many first-time stereo system purchasers content themselves with a receiver, a pair of speakers and a record-playing system at the outset. Often, after experiencing the pleasure of listening to faithfully reproduced music, a tape deck is added. This adds a new capability to a home music-playing system-recording new records, radio broadcasts, live performances, etc. The cassette deck, which uses small pre-packaged tape cassettes, is the most popular tape re cording medium. This is owed to its ease of operation and great improvements made in its ability to record and play back sounds with great fidelity. Amateur recordists who want to do more than just record their favorite musical programs from radio or records may prefer an open-reel tape deck. This permits easier tape editing and, in some cases, simulates the capabilities of professional re cording studio machines in both creative and sound fidelity aspects.

HOW MUCH FOR YOUR FIRST SYSTEM

As you learn upon examining product listings in this directory, it's possible to spend as little as $400 to $500 on a "basic" stem consisting of a receiver, a pair of speaker systems and a record-playing system. Even this relatively low figure can he further reduced by careful shopping. This is especially true if you purchase all of the components you need from one dealer.

Many dealers. in fact, offer complete systems bearing a single price tag that's generally much lower than the sum of the prices of all components included. There is nothing wrong with taking advantage of such "package" deals if the components selected and combined in this way meet your listening requirements.

While $400 to $500 allows you to enter the world of component high fidelity, there are much more costly systems. with correspondingly better performance and greater operating flexibility. There are, for example, speaker systems which by themselves, cost several thousands of dollars. Highest powered. full-featured stereo receivers presently available also sell for more than the $1000 mark. And there are even turntable systems which, alone, cost more than a complete four-component system which, to untrained ears, may he perfectly acceptable.

It has been said that the first few hundreds of dollars you spend on a high fidelity stereo system brings you a long way toward the "ultimate" in sound quality. It's that last 10% or 20% in "fidelity" that is the expensive quest. To many persons. it's worth it, too.

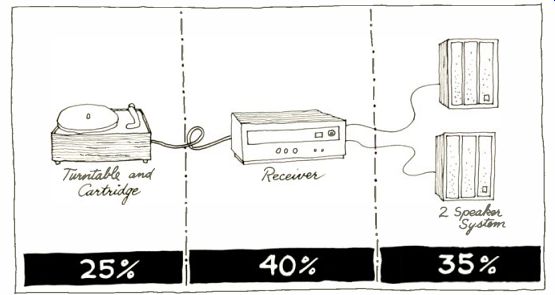

Regardless of how much money you decide to spend for your first component system. it's important that the components chosen be well matched or compatible with each other. If your budget is $500. it makes little sense to spend $350 of that sum on a stereo receiver, and be left with only $150 for a pair of speakers, a turntable system and a stereo phono cartridge. Figure 1 illustrates how to apportion your monies for a basic component system so that no component's performance quality will greatly exceed another. Keep in mind that, in most cases, sound-quality performance will only be as good as that of the poorest component in the system. So buying a "super" component to match only modest-performing ones would be a waste of money in most in stances.

WHAT TO CHOOSE FIRST

Most audio experts agree that, in choosing a component system, the first decision to be made (and perhaps the most difficult one) concerns your loudspeakers. Speaker systems offer the greatest variable in any high fidelity system. What's more, unlike some of the purely electronic elements of a stereo system, it is difficult, if not impossible, to describe the performance of a speaker system in terms of published technical specifications. As you audition speaker systems at your dealer's showroom land that is a basic way to judge speaker qualities) you will

-----------------

Apportioning dollars to a stereo receiver/turntable/speaker system.

--------------

----- Apportioning dollars to an integrated amplifier/tuner/turntable system.

----- Apportioning dollars to a "separates" system.

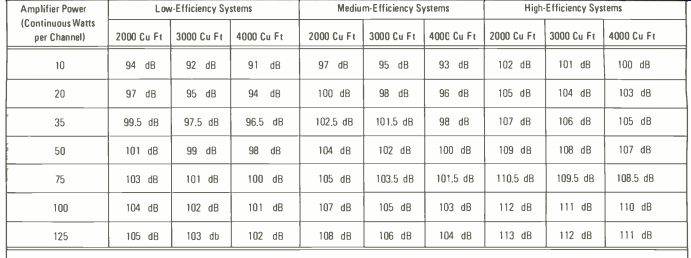

TABLE I-GUIDE TO POWER-AMPLIFIER REQUIREMENTS FOR SPEAKER EFFICIENCY AND ROOM SIZE

Highest Sound Pressure Level (in dB) Possible for a Room of Indicated Volume (in cu. ft)

…. quickly discover that most speaker systems sound somewhat different from each other.

Aside from obvious differences in sonic qualities or "coloration," you might also note that as different speakers are connected for comparison listening tests, some may play louder than others, even though no alteration of volume-control settings has been made on the associated receiver or amplifier. These differences in loudness levels arise because different speaker system de signs result in different speaker system efficiencies. (Many dealers have speaker switching systems that compensate for these differences. Accordingly there may not appear to be any sound output difference.) Speaker efficiency, rather than a measure of sound quality, is a measure of how much sound energy is delivered by the speaker system for a given amount of amplifier energy or power fed to it. Thus, a speaker which delivers I watt of acoustical energy when driven by 100 watts of amplifier power may be said to have an efficiency of 1%.

Many popular speakers have even lower efficiency ratings. Generally, speakers which are small in size (so-called "book shelf" types) and which employ sealed-box enclosures (popularly known as "acoustic suspension" or "air suspension" designs) have relatively low efficiencies, while larger, floor standing models (often equipped with front-baffle cut-outs known as vents or ports, and sometimes featuring so-called passive radiators or "drone cones") usually exhibit higher efficiency ratings. Since over all efficiency may vary (depending upon the type of design) from well below 1.0% to above 10% (for certain types of horn-loaded speaker systems), it is often wise to select speaker systems first. Only then can you have some idea of how much power you will need to properly drive those speakers to satisfactory listening levels of loudness.

Room size also affects the amount of power you will need for your receiver or amplifier. Obviously, a small room such as a den or office will require less audio power than will a large, cathedral-ceilinged living room. Table I should serve as a general guide in helping you to decide how much power you need for your receiver or amplifier, once you have selected your speakers and determined whether they are classified as low-efficiency, medium-efficiency or high-efficiency types. Your audio salesman can help you in making that determination, or you may consult the speaker manufacturer's specification sheet. Ideally it would list the system's sensitivity as well as the mini mum power that an amplifier should have to drive it satisfactorily.

Though speaker sensitivity does not permit you to calculate actual efficiency directly, it does give you an indication of relative efficiency. Speaker sensitivity is generally given in dB-SPL (Decibels of Sound Pressure Level) that will be perceived at a distance of 1 meter from the front of the speaker when that speaker is being fed with a power level of I watt from an amplifier. The higher the dB-SPL rating, the greater the efficiency. In order to relate sensitivity to efficiency (for utilizing Table I). the following guidelines may be used.

Sensitivity. dB-SPL 80 to 85, 85 to 92

Above 92

Efficiency Low Medium High

RECEIVER OR AMPLIFIER POWER

To use Table I, calculate the volume (in cubic feet) of your proposed listening room.

Do this by multiplying room height by length, and then by width. Next, you must decide just how loudly you are going to want to play your music. To give you some idea about loudness levels, consider that when you are seated in mid-orchestra at a live concert performance, you are likely to hear peak sound levels of 90 to 95 dB SPL. If you want the sonic sensation of sitting up close in your home concert hall. 100 dB or even a bit more may be required. If you'd rather be standing where the conductor of a full orchestra is, or if you want the sonic environment of a discotheque, sound levels of 110 dB or even higher may, at times, be required.

It is important to remember that when you double the power fed to a loudspeaker, the sounds you hear do not sound twice as loud.

Rather, you will note only a moderate in crease in loudness level when power levels are doubled. For sound to seem twice as loud, it is necessary to increase power by a factor of ten to one! So if you are coasting along at peak power levels of 10 watts or so, should you wish to make the sound appear twice as loud, you would need to boost power all the way up to 100 watts! If your funds are limited, you would do well to select a speaker that exhibits relatively high efficiency (or high sensitivity ratings.) Picking up a mere 3 dB of speaker sensitivity means you can purchase a receiver or amplifier that delivers half the power you would otherwise need for a given loudness level of sound reproduction. (Note that high or low speaker efficiency is no indication of quality. Rut high-efficiency speakers generally require larger enclosures to achieve the amount of deep bass that a low-efficiency speaker system produces in a smaller enclosure. The smaller enclosure, though, requires a more powerful amplifier.) Our ears tend to play tricks on us; we will generally tend to favor the louder of two pairs of speakers in any comparison test.

Therefore it is important, in comparing the sonic quality of speakers during auditioning tests, that each pair of speakers compared be played at precisely the same loudness as the next pair.

It is also a good idea to start by listening to a few pairs of speakers that cost much more than you plan to spend. Having familiarized yourself with the typically better sound from such speakers, the idea then is to try to find speakers in your price category which come closest to reproducing the costlier sound.

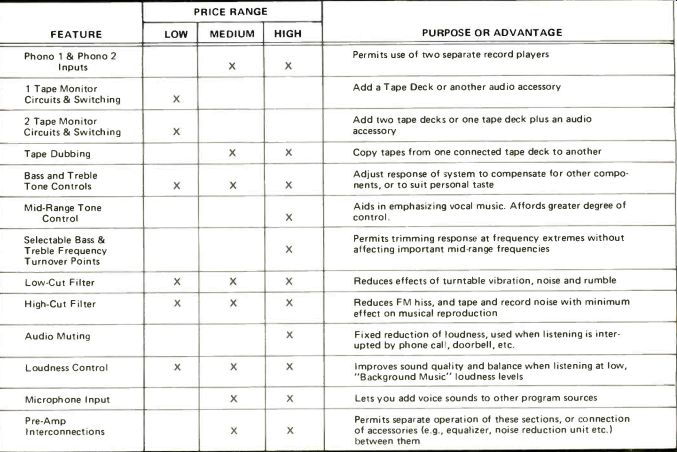

TABLE II--PREAMPLIFIER/CONTROL SECTION FEATURES

-------

CHOOSING THE RECEIVER

Assuming you now know how much power you need from a receiver to properly drive your chosen loudspeakers, it's time to select the heart of your system--the stereo receiver itself. It is, of course, possible to purchase a receiver that can deliver much more power than you need. Some of today's stereo receivers deliver fully as much power as the very highest powered separate integrated amplifiers or basic power amplifiers.

Indeed, if you plan to add additional speakers in other rooms (most receivers can handle two or even three sets of speakers, all connected to the one component and switchable from the front panel), you may want to choose a receiver with a higher-than-now-needed power rating. With two sets of speakers playing simultaneously, power will divide equally between them.

Hence, you would need twice as much power from your receiver for equal sound levels.

Aside from power ratings, there are many other considerations in choosing a receiver.

These may be divided into two general categories: features and specifications of the preamplifier/control section. and features and specifications of the tuner section.

PREAMPLIFIERS/AMPLIFIERS

Table II outlines some of the more popular control features available on today's receivers. In the column at the right of each feature is an explanation of what that feature (or control) accomplishes. Though we have separated the features and controls into low-priced, mid-priced and high-priced categories, you will quickly discover that there is a great deal of overlap. If you spot a feature that appeals to you and it is listed in the high-priced column, the idea is to seek out a receiver in a mid-priced or low-priced category (assuming you are bound by such budget limitations) that manages to incorporate the desired feature.

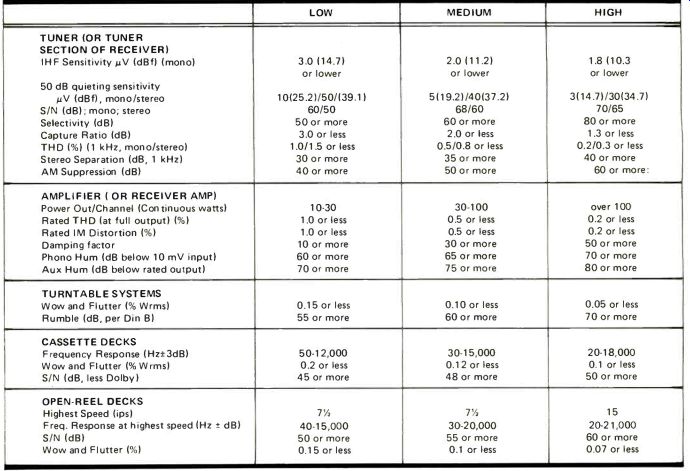

Table IV lists some of the more important specifications which you will want to know about when considering the performance quality of the preamplifier and amplifier sections of the receiver you buy. While most people are concerned primarily with power output ratings of the amplifier section, it is important to remember that this is only one of many performance criteria that must be judged.

Even power ratings are subject to some interpretation. For example, two amplifiers may both be rated at 50 watts per channel of continuous power, but one may boast a harmonic distortion rating of only 0.1% while the other may deliver its rated power with 0.5% total harmonic distortion. Beware of inflated power ratings based solely on mid-frequency capability. An amplifier will generally deliver more power at mid-frequencies (around 1000 Hz) than it can at the audio frequency extremes of 20 Hz and 20 kHz, yet it is at the low-frequency end of the spectrum that greatest power demands are often made upon an amplifier.

Similarly, most amplifiers deliver higher output power when measured with 4-ohm speaker loads than they will with 8-ohm speaker loads, even though most speakers have rated impedances of 8 ohms. A complete power specification (as required by the Federal Trade Commission) will list the continuous power per channel rating and will mention, in the same sentence, the frequency limits over which that full power can be delivered, the impedance at which that power rating is applicable, and the maxi mum total harmonic distortion that may be expected at rated power or at any power level down to a quarter of a watt.

New Amplifier Measurement

Standards have recently been introduced by the Institute of High Fidelity (IHF). Since it takes some time for manufacturers to adopt these standards in their specification sheets, how ever, we elected to use existing references and standards of measurement in compiling Table III.

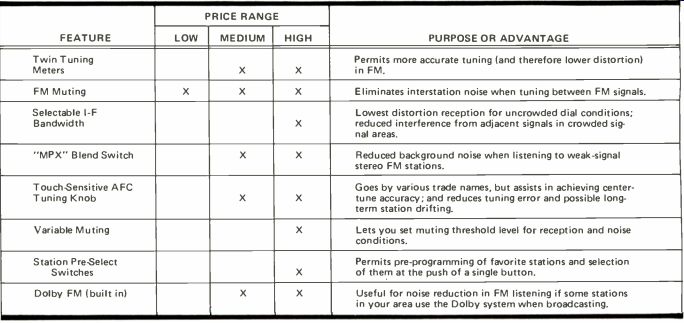

TUNER SECTION FEATURES

With very few exceptions, the AM tuner sections incorporated in most stereo high fidelity receivers are incapable of producing sound having wide frequency response or good fidelity. While most receivers do offer both AM and FM sections, the AM section should generally be regarded as a convenient listening format for news broadcasts, sporting events and other program features which do not particularly benefit from high fidelity reproduction.

As for the FM tuner sections built into receivers, there are wide variations in quality from lower-priced models to the high priced units. More often than not, features and performance tend to decrease as the power and price of the overall receiver goes down. This is unfortunate, since a user does not always require a powerful receiver (having selected high-efficiency speakers) but nevertheless wants top-grade FM radio performance. Some manufacturers are be coming aware of these needs and are no longer sacrificing FM performance as they design lower-powered receivers. The serious FM listener will try to ferret out such design examples in choosing a lower-powered, lower-priced receiver. To assist in that task, we have prepared a brief table of features which may be found in low, mid and high priced FM receivers. Table III summarizes these features, together with brief explanations of their functions and advantages.

In Table IV we have similarly prepared a listing of the more important performance specification ranges for the FM sections of receivers in different price categories. Once again, try to select a receiver in your price category which offers as many of the features and specifications normally found in the next higher priced category as you can.

Regardless of which receiver you purchase, don't overlook the importance of a good outdoor FM antenna. Such an antenna installation can often make a low-priced tuner section perform like a much higher-priced unit not similarly equipped.

CHOOSING A RECORD-PLAYER

Most present-day turntables) systems operate at two speeds. 33 1/3 and 45 rpm, to match all modern records.

Your first concern, as a first-time buyer, is whether to select a single-play or a multiple-play machine. The latter allows you to stack several records (usually around six) and have them play sequentially. The former type requires that you flip the record or place a new record on the turntable when you have listened to one complete side.

Many of the better multiple-play machines can also be used in a single-play mode.

Moreover, many single-play machines have some degree of automation, such as automatic tone arm set-down or lift-off at the end of play.

As you shop for a turntable system, you will be told of the virtues of direct drive (a motor operates at slow speed and its shaft is coupled directly to the center spindle of the turntable) and belt drive (a higher speed mo tor's torque is coupled to an inner rim of the turntable by means of an elastic belt). Both drive systems, properly engineered, can result in a turntable which runs at precise speed, exhibits little audible vibration or rumble and low orders of speed fluctuation commonly known as wow-and-flutter. You will also be confronted with such convenience features as variable pitch control (ability to vary speed by a few percent in either direction, useful if you want to "play along" using an instrument that is not precisely in tune, but otherwise of academic importance), crystal controlled speed accuracy, electronic drive systems, and even a few models capable of being operated remotely. As with all high fidelity component products, you pretty much get what you pay for, and if your main concern is performance. you should be guided by the few turn table specifications listed in Table IV (again, presented in typical ranges based upon price categories), adding those convenience features that are important to you and that you think you can afford.

CHOOSING A PHONO CARTRIDGE

As in the case of loudspeaker selection, judging the quality of a phono cartridge is largely a subjective matter. Of course, the cartridge must be one that will work satisfactorily in the turntable system's tonearm; your dealer can advise you about this. But it is wise to comparatively audition more than one cartridge before making a final choice.

Such "A-B" testing can be conducted at a well-equipped hi-fi dealer's showroom. Re corded material used in such tests should preferably be of your own selection and should include a wide variety of musical se lections with which you are familiar and which you have heard played on a friend's top-quality high-fidelity system.

Most hi-fi cartridges or pickups are moving-magnet types which can be directly connected to the phono inputs on your receiver or amplifier. There are, however, a few moving-coil types (generally more expensive than the moving magnet types) which require either a step-up transformer or additional amplification circuitry to work with conventional receivers.

Check the cartridge manufacturer's literature and the directory listings that appear in this publication to be sure that the tracking force range (given in grams) is compatible with the tonearm adjustment range on the turntable system of your choice.

ADDING A TAPE DECK

Your choice of a tape deck (cassette or open-reel) relates closely to your interest and involvement in home recording. If you are very serious about making your own tape recordings, especially of live performances and with such options as multi-channel overdubbing, echo effects, mastering for other tape copies, etc. you may want to think in terms of an open-reel machine. For more casual recording projects, you will want to consider a top-performing stereo cassette deck. Modern cassette decks will typically include a built-in noise reduction system such as Dolby (other noise-reduction techniques are also available) and switching facilities that enable you to use a variety of tape formulations such as ferric oxide. ferric-chrome combinations and chromium dioxide.

Most cassette decks are two-head designs which combine record and play functions into one head (the other head is for erasing previous recorded material from the tape so that it can be used over and over again). A few costlier cassette decks offer three heads. This enables you to monitor recordings by means of a separate playback head an instant after they are made.

While cassette technology (both in the machines themselves and in the tape cassette packages) has made giant strides in the past few years, higher-speed open-reel machines still can produce wider frequency response with less residual tape hiss or noise and with greater dynamic range than even the highest priced cassette decks, though this gap is constantly being narrowed. The ease of handling possible with cassettes has contributed to the popularity of this tape re cording format.

Though there exists a growing library of pre-recorded cassettes (there are practically no pre-recorded open-reel tapes available).

if pre-recorded rock and pop music are your forte, keep in mind that 8-track cartridges offer a much larger catalogue of pre-re corded material than is available on cassettes. The drawbacks of an 8-track tape deck include absence of a fast-forward and rewind facility, few models that can also re cord, and greater tape storage space requirements compared with cassettes.

Table IV details the most important specifications for both open-reel and cassette tape decks and gives you an idea of what levels of performance you may expect in low, medium- and high-priced machines of each type.

Armed with the foregoing information, you should now be in a good position to examine the models listed in the accompanying Directory, referring to the glossary of technical terms that precedes it. When you narrow down the number of models in each category to a reasonable group, perhaps adding stereo headphones and other components, visit your local audio dealer and discuss your plans with him.

--------------------------------

TABLE III-FM TUNER FEATURES FEATURE PRICE RANGE

PURPOSE OR ADVANTAGE LOW MEDIUM HIGH

Twin Tuning Meters

Permits more accurate tuning (and therefore lower distortion) in FM.

FM Muting

Eliminates interstation noise when tuning between FM signals.

Selectable I-F Bandwidth

Lowest distortion reception for un-crowded dial conditions; reduced interference from adjacent signals in crowded signal areas.

"MPX" Blend Switch

Reduced background noise when listening to weak-signal stereo FM stations.

Touch Sensitive AFC Tuning Knob

Goes by various trade names, but assists in achieving center-tune accuracy; and reduces tuning error and possible long term station drifting.

Variable Muting

Lets you set muting threshold level for reception and noise conditions.

Station Pre-Select Switches

Permits pre-programming of favorite stations and selection of them at the push of a single button.

Dolby FM (built in)

Useful for noise reduction in FM listening if some stations in your area use the Dolby system when broadcasting.

--------

TABLE IV-TYPICAL SPECIFICATIONS OF HI-FI COMPONENTS LOW MEDIUM HIGH TUNER (OR TUNER SECTION OF RECEIVER) I H F Sensitivity µV (dBf) (mono) 50 dB quieting sensitivity µV (dBf), mono/stereo S/N (dB); mono; stereo Selectivity (dB) Capture Ratio (dB) THD (%) (1 kHz, mono/stereo) Stereo Separation (dB, 1 kHz) AM Suppression (dB) 3.0 (14.7) or lower 10(25.2)/50/(39.11 60/50 50 or more 3.0 or less 1.0/1.5 or less 30 or more 40 or more 2.0 (11.2) or lower 5(19.2)/40(37.2) 68/60 60 or more 2.0 or less 0.5/0.8 or less 35 or more 50 or more 1.8 (10.3 or lower 3)14.7)/30)34.7) 70/65 80 or more 1.3 or less 0.2/0.3 or less 40 or more 60 or more:

AMPLIFIER ( OR RECEIVER AMP)

Power Out/Channel (Continuous watts)

Rated THD (at full output) (%)

Rated IM Distortion 1%)

Damping factor Phono Hum (dB below 10 mV input)

Aux Hum (dB below rated output) 10-30 1.0 or less 1.0 or less 10 or more 60 or more 70 or more 30-100

0.5 or less

0.5 or less 30 or more 65 or more 75 or more over 100

0.2 or less

0.2 or less 50 or more 70 or more 80 or more

TURNTABLE SYSTEMS

Wow and Flutter (% W_rms) Rumble (dB, per Din B)

0.15 or less 55 or more

0.10 or less 60 or more

0.05 or less 70 or more

CASSETTE DECKS

Frequency Response (Hz± 3dB) Wow and Flutter (% W_rms) S/N (dB, less Dolby) 50-12,000

0.2 or less 45 or more 30-15,000

0.12 or less 48 or more 20-18,000

0.1 or less 50 or more

OPEN-REEL DECKS (Highest Speed i/ps)

Freq. Response at highest speed (Hz ± dB) S/N (dB)

Wow and Flutter 1%) 7 1/2 40-15,000 50 or more

0.15 or less 7 1/2 30-20,000 55 or more 0.1 or less 15 20-21,000 60 or more 0.07 or less

----------------------

----------------

Also see: