I read recently [early 1996] of a survey taken to get a feel for the “man in the streets” attitude concerning big-screen TV. I don’t recall the details, but one thing stands out. When shown a large, front-projected video image, everyone wanted it. And they would pay up to $800 to get it!

Welcome to the real world, neighbor. If you’ve been keeping up with the market—as those men and women in the street obviously had not—you know that $800 will buy you a good, but hardly top-of-the-hue, direct-view television. It won’t buy you even the cheapest rear-projection TV (PTV).

As for a separate video projector and screen, forget it.

But a separate projector and screen remain something of a holy grail in home theater. Why? Because a projector is the only way to achieve a genuinely BIG picture—bigger than all but the biggest PTVs. But this very capability means that you, as a consumer, must be aware of the limitations of video projectors and screens, and not demand more than they can deliver. Video projectors range in price from around $2000 up to a level that will still buy you a modest house in some parts of the country. And this is one field in which you definitely get what you pay for.

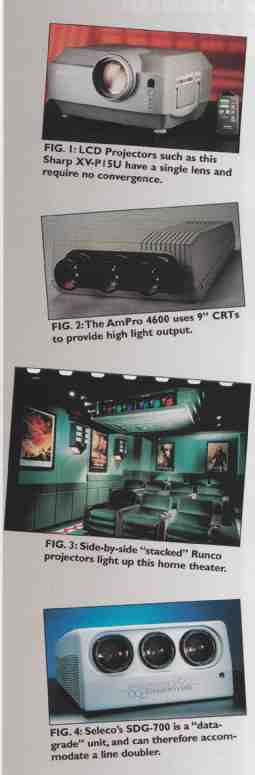

There are two common types of video projectors currently available: CRT and LCD. A CRT projector uses three separate cathode ray tubes—one each for red, green, and blue—firing through three separate lenses. The three CRT/lens assemblies must be carefully aimed or converged to produce a single image on the screen. LCD projectors (see Fig. 1), on the other hand, make use of individual liquid-crystal pixels to form the picture—much like the image on a laptop computer.

Each method has its proponents. LCD projectors are easier to set up. They have only a single lens, so convergence is not a concern. That single lens also has a variable focal length, so the distance from the projector to the screen is more flexible—making for more convenient placement. The projector- to-screen placement of a CRT projector is relatively fixed. Furthermore, tube replacement on a CRT projector can be expensive, while the LCD light source—a single bulb, usually metal halide—should be far cheaper.

This is not an insignificant consideration; the tubes in a CRT projector will lose about half their output in roughly the first year of normal use (2 to 3 hours a day). This is simply a limitation of the available technology those tubes are driven hard to produce that big picture. Fortunately, the brightness loss will slow down dramatically after the first year, and the tubes will last for thousands of addition al hours. But you will notice after that initial year that the picture is not as snappy as it was when the projector was new. And you cannot recover what you’ve lost by simply cranking up the contrast control without causing the picture to deteriorate in other important respects.

So why would anyone choose a CRT-based projector instead of an LCD unit? Simple. At the present state-of-the-art, CRT projectors, dollar for dollar, produce a better picture than any LCD device—with brighter, more accurate colors, higher light output, and a wider usable contrast range.

As big as hug can be

In general, the more you pay for a video projector, the bigger and sharper the image. But there are limits. With even the best CRT projectors (using 7-inch tubes, the most common size), a 7-foot—wide (not diagonal) screen is the practical limit. Beyond that, although you get a watch- able image with a good projector the quality—particularly the available usable light output—deteriorates rapidly. If you want a really good 10-foot—wide picture, be prepared to spend the big bucks for a projector with bigger tubes—preferably 9 inch (see Fig. 2). And be prepared to drive them hard and be faced with expensive projection-tube replacement every year or so to maintain the brightest possible, high-quality image.

Another option for a bigger, brighter image, one advocated by Joe Kane of the Imaging Science Foundation, is to use two projectors, stacked and converged together on the same screen (see Fig. 3). If you use projectors with 7-inch tubes, stacking may actually be a more “economical” alternative than using a single projector with 9-inch tubes, believe it or not. While not cheaper in total cost, you get more light output per dollar with two good 7-inch projectors than with a single 9-inch one. Of course, stacked projectors are an invitation to regular visits by your installer to touch up the convergence—very likely much more frequent visits than with a single projector. Remember, you are paying serious money for that two-projector setup, and you don’t want it “off” even a little. Unless you have a long-term con tract with a nearby installer, or are pre pared and qualified to do the convergence yourself, I suspect you would be better 0 with a single projector. But stacked projectors can produce a big, eye-popping image, no doubt about it.

====

Widescreen, Letterbox, and the DVD

---Anamorphically squeezed image as stored on disc.

----Unsqueezed image fills full frame.

The most common means of fitting a widescreen image into a standard 4:3 video frame is the commonly seen (and much maligned) letterbox. But there is another to way: keeping the image the full height of the screen and squeezing it laterally until it fits. This is dire analogous to the squeeze which is used store widescreen Panavision (and similar formats like the old CinemaScope) images on 35mm film stock. To restore the proper look to the picture it must be unsqueezed on playback and, in the case of video, displayed on a device capable of showing the wider ratio, i.e., a widescreen television. The squeezing and unsqueezing in film are done by devices known as anamorphic lenses, and the same term is also appropriate when referring to the technique in video To date, however, the only widescreen pro gram material widely available to the general public has been letterboxed films. How do these differ from an anamorphically squeezed, then unsqueezed transfer? With a letterbox video, the black bars are essentially discarded vertical resolution the horizontal scanning lines in those bars are unused With a 16 9 letterboxed picture, instead of 480 usable lines in the image we see only 360 lines-a loss of one-quarter of the available resolution. If a film is transferred to video anamorphically (i.e., squeezed so that the full vertical height of the picture is used), when it is unsqueezed by a widescreen-compatible television set, all the scanning lines will be available in the recreated image.

Because they require a special television for proper play back however anamorphic laserdiscs are unlikely to become a viable consumer format. A few special-purpose anamorphic laserdiscs have been pressed-Toshiba has made a few to demonstrate their widescreen sets-but they are not for sale to the general public. Enter DVD.

The digital nature of DVD allows for an elegant solution to this incompatibility. At the software producer's option, the image is recorded anamorphically on the disc, and several user playback options are provided. For playback on standard televisions the signal is unsqueezed in the player then sent to the television one of two ways. For full frame, pan-and-scan playback (of the sort familiar to most viewers) codes recorded on the disc along with the film direct the player to dynamically scan the signal, on a scene by-scene basis, to present the most. Important part of each scene in a 4:3 format. For viewers with small sets or an aversion to letterboxing this is the preferred option.

Alternately the player will convert the unsqueezed picture into a conventional letterboxed image, which will appear on the screen as do today's letterboxed pictures, complete with the unused scanning lines in the black bars. But the last mode is the most exciting; the anamorphic image may be tapped directly from the player, then fed to a widescreen set where it is unsqueezed and displayed in all its higher resolution, widescreen glory.

=== ====

Making the grade

Until recently, there were two general categories of video projectors (LCD vs. CRT considerations aside) of which buyers needed to be aware. Most lower cost projectors are video-grade devices, which means they have a fixed horizontal scanning frequency of 15.75 kHz, the same as a conventional television set. Video- grade projectors work well with any standard video source, including laserdisc, VCRs, etc.; but they cannot be tied to computers and do not provide computer-grade resolution. For that, a data or graphics-grade projector is required (see Fig. 4). These units can scan at much higher frequencies, and most have multi-scan capability which means they can accommodate a range of horizontal scanning frequencies. Keep in mind that projectors are primarily sold in the commercial and professional markets, where video presentations using computer graphics are important.

Do you need this capability at home? You do if you plan to add a device called a line doubler (see sidebar, “Seeing Double”). Briefly put, a line doubler converts the interlaced scan used to form NTSC video images into a progressive scan of the sort found on most computer monitors. If implemented properly, a line doubler dramatically reduces the visibility of scanning lines, which can otherwise become quite noticeable (and annoying) with the large images sought after for home theater.

However, good line doublers are expensive—ranging from around $3500 to $15,000 and more. But they not only make bigger screens practical, they allow you to sit closer to that screen than would otherwise be possible. And a bigger; closer, sharper picture means IMPACT.

If, like most of us, a more modestly- priced, non-doubled picture is your only practical option, I would recommend a maximum 6-foot—wide screen. Be pre pared to sit a little further back if scanning lines bother you. In evaluating the two video-grade projectors reviewed elsewhere in this issue, I used an 84-inch diagonal screen (4:3 aspect ratio, thus 67 inches wide). Seated at a distance of just over 12 feet from the screen, I was seldom bothered by scanning lines, but they were visible. For many people, sitting 15 or 16 feet back from a screen this size (or a slightly smaller screen) would further minimize scanning lines, albeit at the sacrifice of the overall drama of the picture.

With the imminent introduction of the new digital video disc (DVD) format sometime this year or early next, there is one additional consideration necessary in choosing a video projector. DVD will provide, at the software producer’s option, a true widescreen signal. While all video projectors can reproduce a 43 or letterboxed widescreen image, only a few projectors currently on the market (most of them in the most expensive category) can “unsqueeze” an “anamorphically squeezed” signal from a DVD. (Of the three projectors reviewed in this issue, only the Runco 980 can perform this feat). For an explanation of what this means (anamorphic? unsqueeze?), and why it might be important to you, see the sidebar, “Widescreen, Letterbox, and the Digital Video Disc.”

With a video projector; you also have the choice of either a front- or rear-projection setup. There are translucent screen materials that allow you to mount the projector behind the screen, providing the rough equivalent of a one-piece rear-projection set, only (usually) with a larger picture. Video projectors have the capability of reversing the picture (and inverting it for ceiling mounting) so that it looks correct from the other side in rear-screen applications. While a rear- projection setup hides the projector [ allows slightly more ambient light in the room while viewing.], the tradeoff is the need for lots of space behind the screen. We’re talking 10 to 12 feet or more for even a 6- foot—wide screen. There are manufacturers who make special frames which use mirrors to conserve space in such a setup, though these rigs are not cheap.

Most people who opt for a video projector mount it in front of the screen, thus the somewhat inaccurate but common terminology “front” projectors. In this configuration, the projector can be suspended from the ceiling or floor-mounted, usually inside a table. The exact placement of a projector in relation to the screen is critical; the further a projector is mounted from directly in line with the screen, the more adjustment range is required to get the picture geo metrically square. This is yet another area where a knowledgeable and experienced installer comes into play.

Wherever you mount the projector, you will need a screen. That is the subject for another article (elsewhere in this issue), but it is an expense you must plan for. Screens aren’t cheap. A good, reason ably sized, fixed screen with a metal frame will probably cost you close to $1000, depending on size. Add retracting capability or other bells and whistles (variable aspect ratios, etc.), and the price escalates rapidly.

FIG. 1. LCD Projectors such as this Sharp XP-15U have a single lens and require

no convergence.

FIG. 2. The AmPro 4600 to provide high light output.

FIG. 3: Side “stacked” Runco projector light up this home theater.

FIG 4: Seleco’s SDG-700 is a “data grade” unit, and can therefore accommodate a line doubler.

Living with it

Living with a video-projection system requires a few lifestyle adjustments. Among the most important of these is a properly set up viewing environment. This is an article in itself, and indeed, you’ll find one elsewhere in this issue. Here, I will simply touch on the most important single item: ambient light. Or, rather, the lack of it. To get the sort of performance from your projector you paid for; the room must be totally dark. No lights on. No light leakage from outside.

A video projector is best reserved for serious, dedicated viewing, not for casual TV watching. While it is possible to watch brightly lit program material (sports, etc.) in subdued room lighting and still follow the action, it is a waste to use an expensive projector this way. Turn off the lights to really enjoy the experience you paid for. For casual watching, use another set. Just as an exotic sports car is not a practical only car for a family, a video projector is not a practical only TV for anyone who does both serious home-theater and casual television watching.

Your new video projector will of course be great for cable movies and programs such as Star Trek, but don't expect the same quality you get from laserdisc unless you own a serious satellite dish and receiver.

And because most video projectors do not have built-in television tuners, you will most likely use the tuner built into your VCR for broadcast reception. If you frequently watch one show while taping another, you will now need two VCRs.

A video projector requires not only expert setup, but regular maintenance to perform at its best. And this, at last, is where we come to the subject of where to see and buy a video projector. Except for some of the least expensive LCD models, you won't find them in Circuit City. Good Guys knows nothing about them, either. Your best bet is to find a dealer who handles custom installations,

Check out their in-store displays, if they have them. Also check with past customers to determine how satisfied they are with the product and service. Good customer support is even more important with video projectors than technical help-lines are for computers-and with a projector, the help should be nearby.

Take a look at past installations, if you can, using good-quality program material. A video projector, even an "inexpensive" one, is a significant investment. You want to do everything you can to increase your chances of a positive result, [ good sources for installer references are the Custom Electronic Design and Installation Association (CEDL4), which can be reached at 800-CEDL'130, and the Imaging Science Foundation (ISP) 407-997-9073.] After initial setup, I recommend that the installer pay a return visit about two months later to re-tweak the convergence and adjust out any minor problems. Then, perhaps every six months, you should plan on and budget for regular convergence tune-ups. Here again, the comparison to an exotic sports car is apt.

One final note: a really big image will magnify all the blemishes in the program material. If you're unhappy with the quality of your cable feed now, expect to be outraged when you see it on an 84-inch-wide screen! Even with laserdiscs, don't expect film quality. The best video projectors with the best line doublers come remarkably close to good projection quality as seen in atypical movie theater. But they still can not equal first-class projection of a first class print in a first-class theater Few of us have experienced the latter, but those who have, won't soon forget the experience. Video isn't there-yet.

Does getting a video projector sound like a project? It is. It's not the same as going to the video store, pointing, and waiting for delivery. But it is definitely worth it. There are a lot of good home theaters built around direct-view monitors and PTVs. Great ones are built around video projectors.

== == ==

[adapted from 1996 Stereophile Guide to Home Theater article]