Substandard commercial "software"--discs, tapes, and FM broadcasts--continues to frustrate our attainment of the elusive goal of complete sonic fidelity

By Craig Stark

OVER the years, not a few articles in these pages have explored different aspects of the central issue of high-fidelity music re production: how to produce at the listener's ears the same sequence of instantaneous variations in barometric pressure (otherwise known as "sound") that took place at the original live performance. Audiophiles have devoted enormous amounts of time, effort, and hard cash to the achievement of that goal, with results that range from the weird to the wonderful. And everyone agrees--except for a few diehards cherishing their mono tube equipment that the fidelity of today's components is higher than ever and that even greater technical marvels are waiting just over the horizon.

But, in the last analysis, even if we were to attain perfection in amplifiers, speakers, record players, and recorders, even if we were to install them in an acoustically perfect listening room (may we all live to see that day!), one potential limiting factor would still remain: the "software" media, the tapes, discs, and FM broadcasts used to store and to transmit the original sound. In short, if there is anything wrong anywhere in that long, complicated procedure that starts at the recording session and ends at the pressing plant or tape-duplicating facility, your playback components can do very little to set it right. Tone controls, noise-reduction systems, and the like can rectify minor errors, but major faults will be reproduced with dismaying fidelity.

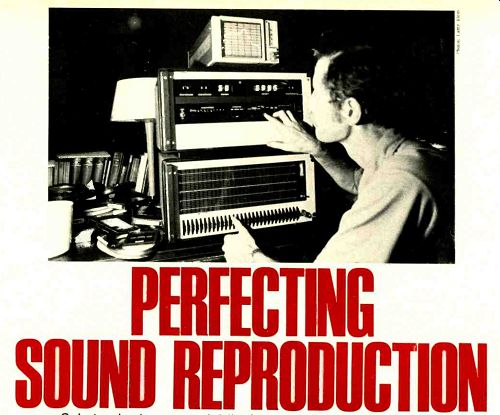

The immediate question, then, is just how well the software people do their jobs. In some cases, thanks to today's superb equipment, remarkably well. A good studio recorder, for example, has a frequency response that easily spans the whole range of human hearing with no audible deviations, and it has in addition a signal-to-noise ratio well in excess of 60 dB. To put this figure in a more familiar context, the tape hiss heard from such a profession al recorder will be far less than the noise (breathing, coughing, squirming, etc.) produced by the quietest audience at a live concert. The catch is, of course, that very few people get to hear these 60-dB or better master tapes. The sound source for most of us has to be the commercial software- discs, prerecorded open-reel, cassette, and cartridge tapes, and FM broadcasts. And so, when the editors of STEREO REVIEW asked me to initiate an investigation into the comparative performance of today's "pro gram sources," it was to these "real-life" musical artifacts that I turned. My first step was to obtain a "real-time analyzer" (RTA) and subject a large number of tapes, discs, and broadcasts to its electronic scrutiny. The RTA, which can instantly display the frequencies present in a given signal (together with their relative strengths), provided a most efficient readout of the present state of the recording (and broadcasting) art. (The accompanying box gives some details of the test approach.) The best place to start in this comparison is with the question of frequency response, which we will define, for our purposes, as that range of musical tones and overtones from the deepest bass to the highest treble harmonics that human auditors can hear. When discussing high-fidelity equipment, we tend usually to consider a minimum frequency-range specification as extending from 20 to 20,000 Hz ±3 dB. With those figures in mind, then, a quick examination of Photo No. 1, one of a number made during our tests, may prove something of a shock. It shows the highest levels achieved in each third of a musical octave during the concluding 32 seconds of Stravinsky's Firebird Suite ( Columbia disc M 31632). But something seems to be terribly wrong, for the bass and treble ends of the frequency-response curve, far from being "flat," are both down by about 30 dB!

----------------

THE REAL-TIME ANALYZER

THE question of what frequencies are present and in what amounts in the music recorded on tape or disc cannot easily be answered without some very sophisticated measuring equipment. As an example of the problem: how does one measure a cymbal crash embodying a multitude of different frequencies-some fundamentals and some harmonics- all at different strengths and all constantly changing? The one instrument that can handle such a task is known as the real-time analyzer. The General Radio Model 1921 we used to produce our test data divides the audio input signal into thirty 1/3-octave segments over the range of 25 to 20,000 Hz. Each separate segment-or band-is displayed and stored individually as on a vertical bar graph, the height of the bar representing signal strength.

The center frequency of each segment is given by the numerals at the base of each vertical readout "bar." Another aspect of the 1921's performance is its provision of a choice of several integrating times.

This means that the instrument can be set up to display on its storage oscilloscope energy ranging from under a second up to 32 seconds in duration.

We wish to thank General Radio for their cooperation in supplying the Model 1921 Real-Time Analyzer, the essential data-collecting tool for this investigation.

-------------------------

Before you are impelled to write an irate letter to Columbia Records questioning their product (or to us, questioning our procedure and apparatus), it would be worthwhile to consider first the very necessary distinction that must be drawn between "frequency content" and "frequency response." Your ears will tell you that the frequencies present in music obviously vary from moment to moment.

But, sampled over a period of time, the proportion of lows, middles, and highs (at least for the classical repertoire) is typically as represented by Photo No. 1. In other words, most of the energy of this (and other) music occurs in the mid-range. This statistical sampling of the levels of each of the various frequencies represents the frequency content of the music. Frequency response, on the other hand, refers to the performance of a reproducing or recording system or component intended to process the music fed into it. The frequency response of audio equipment should be flat, then, even if the frequency content of the music isn't. If, for example, in the original music, the seventh harmonic of a 2,000-Hz tone (14,000 Hz, that is) produced by an instrument is 20 dB weaker than the 2,000-Hz fundamental tone, the harmonic should be recorded and reproduced exactly 20 dB down-no more, no less. If the reproducing equipment involved were to introduce an additional loss (or increase) at 14,000 Hz, musical fidelity would suffer.

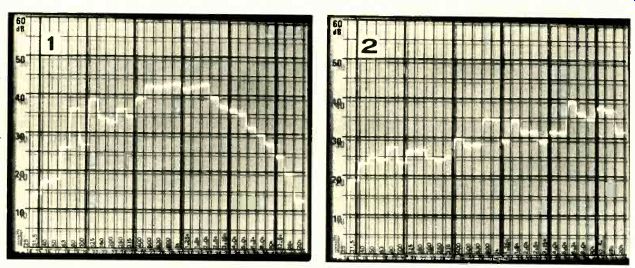

Although it provides useful information, a disc's frequency content averaged over some specific time period does not tell the whole story. For one thing, not all "average" curves resemble Photo No. 1. Photo No. 2, for example, does not. It is a frequency-spectrum analysis of the final second of the Peace Train selection from Sheffield Records' sonically superb disc "The Missing Linc" (S-10), which consists of a very loud note from a finger cymbal of the type used in Near Eastern belly-dance music.

With close miking, the cymbal produced a searing burst of sonic energy over fully half the audible frequency range. As anyone who has ever heard this recording will know, signals this potent, particularly in the high frequencies, are almost never encountered on the usual commercial discs. (According to the producer of this one, even though specially de signed electronics were used in the making of this direct-cut disc, the struck cymbal managed to over load every stage in the recording chain. It did not, however, cause any obvious deterioration in the overall sound, nor did it result in any obvious loss in high-frequency response.) There is, in addition, a second and even more important point to be noted about frequency con tent and frequency response, and it parallels the more familiar debate about how much amplifier power one really needs. In that controversy, the proponents of pecuniary practicality argue that most of the time our amplifiers loaf along putting out a watt or two at most, so who needs the big 300 watt brutes? On the other side, the high-horsepower advocate contends that instantaneous musical peaks can be as much as 20 dB higher than average levels, and, translated into power requirements, 20 dB is a ratio of 100 to 1. I tend to side in this dispute with the high-power purist, since, during listening tests in my own home, with speakers of moderately low efficiency, I have driven even a "super-power" amplifier into severe clipping by playing it at a level that no one found excessively loud.

Analogously, the frequency-response demands of music can, for brief moments, far exceed the specific frequency content shown in our scope photos.

Therefore, if they are to operate without overload, both recording and reproducing systems must be able to handle those momentary frequency demands, not just long-term (or even short-term) aver ages. This is not always possible, however, and disc-cutting engineers, tape duplicators, and FM broadcasters are therefore led into a series of sonic compromises.

Consider, for example, the deepest bass note in the musical spectrum, the low C (16.351 Hz) produced by a 32-foot organ pipe. I know that it can be recorded, because I've done it--though there are precious few speaker systems that will reproduce it at anywhere near its full relative strength. But the question faced by the recording engineer is not really whether 16-Hz can be recorded, but whether it should be. For one thing, loud, low bass notes pro duce exceedingly wide undulations of the record groove, which of course, cuts into the number of grooves (and therefore the amount of music) that can be accommodated on a given disc side. If there is a great deal of low bass material on a disc, the playing time of that side is shortened considerably.

Also, those very large groove excursions may cause tracking troubles-- groove jumping--for all but the very finest phono cartridges. Then, too, recording with a flat response to such a low frequency tends to exaggerate recording-studio noise (the air-conditioning system, for example), to say nothing of the fact that FM broadcasts are deliberately rolled off from 50 Hz on down. Given all this, it is hard to fault the recording engineer who compromises a little on the full level of that 16-Hz organ pedal.

-----------------------

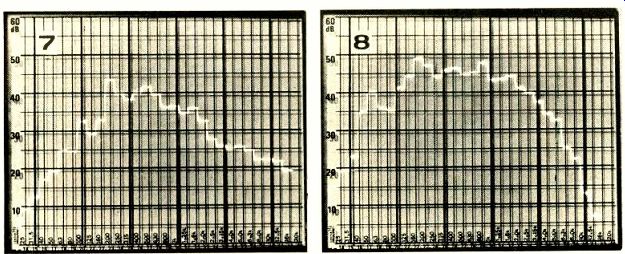

Photo 1 shows the final half-minute of a Columbia Firebird (M-31632); the frequency vs. energy distribution is typical of recorded music. Photo 2 shows a highly atypical recorded signal: the last note of the Peace Train selection on Sheffield's disc "The Missing Line."

----------------

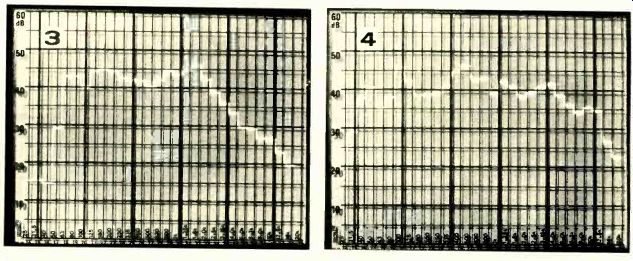

Photo 3 is representative of loud "hard rock" music.Note that energy levels are virtually 'fiat" from 70 to 2,000 Hz. In Photo 4 the very wide frequency range and high energy levels of modern electronic music are indicated.

------------

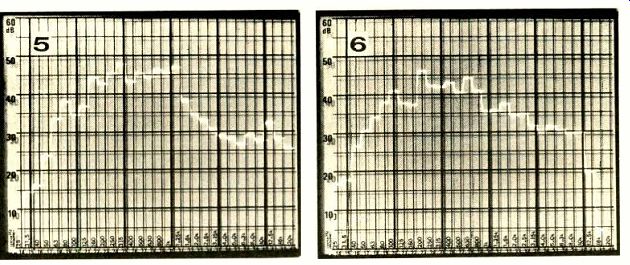

Photo 5 is an integration of Deodato's adaptation of Strauss' Also Sprach Zarathustra. The slight boost around 10,000 Hz accentuates percussion sounds. Photo 6 is from the Manilas de Plata selection on STEREO REVIEWS Demonstration Cassette.

---------------

Photo 7 shows the same material as Photo 6, but was taken from the STEREO REVIEW Stereo Demonstration Disc. Note the difference in levels above 10,000 Hz. Photo 8 is typical of eight-track cartridges, exhibiting little musical energy above about 6,000 Hz.

Turning to the treble end of the musical spectrum, we find the picture even worse, for it is complicated by the process known as "equalization." Used in much the same way on tapes, discs, and FM, high-frequency equalization is designed to cut down the level of subjectively perceived noise (hiss) during playback. The fact that most music has a frequency content similar to that shown in Photo No. 1 means that one can boost the high end (for noise-reduction) during the recording or transmission process--provided, of course, that a corresponding treble cut is built into the listener's play back system. This restores the original frequency balance (as if the treble hadn't been fiddled with at all), and that high-frequency cut in the reproduction process also lowers the audible surface noise. tape hiss, and other disturbances that entered after the boost; the result is cleaner overall sound.

The rub comes, of course, when the musical picture resembles that in Photo No. 2--which is to say that the music has a lot of very high-level treble content. Here the tape recorder, the FM transmitter, and the disc cutter all run into trouble. In the first place, every time the frequency goes up by one octave (say, from 1,000 to 2,000 Hz), the cutter stylus must make twice as many wiggles in the groove every second, and twice as much power must be fed to it to permit it to do so. The additional high-frequency boost of the equalization curve must be added as well, and that requires still another doubling of power for each successive octave, thus quadrupling the drive requirement. This means that if 1 watt is needed to cut a given level at 1,000 Hz, it will take 256 watts to cut the same level at 16,000 Hz-at which point the cutting head will probably go up in smoke from gross overload of its power-handling capacity (a friend of mine, trying to make an impressive demonstration record, once burned out three cutter heads- at $1,000 each- in a single day). Small wonder, then, that disc-cutting engineers sometimes roll off the high frequencies a bit, comforting themselves with the knowledge that very few home phono cartridges could track that hot a groove anyway. It must be stressed that to call attention to these limitations in the recording (and broadcast) process is not to impugn the integrity of our home music sources, for, despite their imperfections, they do a remarkably good job.

HAVING looked at (while listening to) many hundreds of musical waveforms displayed on the RTA's oscilloscope, I have come to some useful generalizations. For example, scope Photo No. 3 is typical of the "hard rock" sound, with heavy bass and a strong mid-range- around 80 and 2,000 Hz, respectively. Photo No. 4 is representative of to day's electronic music which, more than any other type, contains (and therefore demands) equal power throughout the frequency spectrum. The Deodato take-off on Strauss' "Thus Spoke Zarathustra" (CTI 6021) shows (Photo No. 5) an ear-bruising peak at 10,000 Hz, a sound that makes the closing of the Firebird (not noted for its quietness!) seem tame by comparison. However, it became apparent that if one carefully chose specific moments during a performance to sample the frequency content, the energy distribution in any one kind of music could be made to look like any other. This means that full power capability across the full bandwidth is needed in all parts of the recording/reproduction chain if we are to do full justice to music. We don't have that capability at the moment, of course. though we continue to get closer.

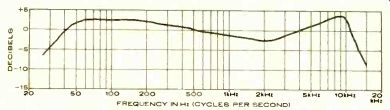

In some cases, I was able to compare the same musical passages on both cassettes and discs. Photos Nos. 6 and 7 show the RTA's readout for one such comparison. Note that the high-frequency energy above 10,000 Hz present on the disc was not only definitely reduced in the cassette version, but there was an apparent attempt to distract attention from the loss by boosting the frequencies just below it. Figure 1 shows a composite curve derived from a number of cassette and disc samples.

FREQUENCY IN hz, (CYCLES PER SECOND)

Fig. 1. The curve shows how frequency content of a random se lection of cassettes differed from that of typical LP discs. The 0-dB line corresponds to the LP discs' frequency responses.

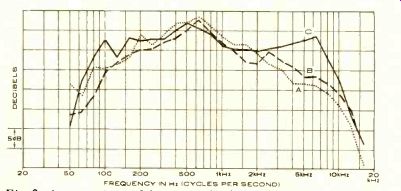

FREQUENCY in Hz (CYCLES PER SECOND

Fig. 2. A comparison of the spectral balances of two disc versions of J. S. Bach's "Goldberg" Variations (A and B) with an unprocessed master tape of the same music, fresh from the recorder.

Eight-track cartridges varied so widely in their quality that I could draw no conclusions other than that they contained a lot of hiss and that some were sonically simply terrible (Photo No. 8). By contrast, FM broadcasts showed, on average, a frequency distribution surprisingly similar to that of the discs on the various kinds of music. (It is worth noting, however, that even within the limitations in band width and high-frequency capability imposed by the present FCC rules, some stations obviously are putting out a better audio signal than others.) Since the disc is still (as of this writing, at least) the dominant medium in our music listening, there is another important question still unanswered: Just how close do commercial discs come to their original master tapes? To provide specific answers, we would have to make direct A-B comparisons be tween the two-a privilege not usually available to an audiophile. Fortunately, I had on hand my original 15-ips master tape of a harpsichord performance of Bach's "Goldberg" Variations. Although I could not compare it with its own disc version (since it has yet to be released), I did compare it measure for measure with two other commercial disc versions. The results (Figure 2) were quite surprising. All three curves on the graph are averages of the same measures of the Variations-A and B are the two discs, C is the master tape. The rise around 6,000 Hz on curve C gives the instrument a far greater sense of presence and openness (one noted critic thought it the best harpsichord sound he'd ever heard in recording), but, unfortunately, when the record comes out I suspect it may well sound like the other two.

The implications that may be drawn from this informal study are several. For one, it is clear that the "old-fashioned" LP record at its best is an information-storing marvel; if it does not realize its fidelity potential with every release, we must therefore blame not the medium, but the way it is being used.

In short, support your local record company when its product is good. As for cassettes, the best home recorded (dubbed) examples played back on the best machines can sound remarkably close to the best disc, but the commercially prerecorded cassette still has a long way to go. Dolby has brought the hiss level of the prerecorded cassette down to a bearable level, but someone else will have to provide the over-10,000-Hz frequencies so sadly lacking in most of today's product. It is not likely that duplicators will make improvements in this area until consumers demand it, because the better tape and improved duplication equipment required are expensive.

The eight-track format has always had a potential edge on the cassette simply because it runs at twice the speed (it has its limitations too-no reverse, and the track-switching system makes it unattractive for much symphonic music). Manufacturers have yet to take advantage of the medium's fidelity potential, however, undoubtedly because so far the market (principally automotive) simply hasn't demanded it.

But there is a straw in the wind: a few Dolbyized eight-track units have now appeared. There is room for improvement in FM broadcasts as well. There is very little live-performance music going out over the airwaves these days, so broadcast stations, like the rest of us, have to be content with the fidelity levels present on commercial discs and tape. But there is no reason why they should contribute further sonic degradation beyond that irreducible mini mum involved in the broadcast process.

All our sound-reproduction media, in short, can stand improvement, and the technology is there to accomplish it. What is lacking, oddly enough, is public interest- there is still no large-scale demand for discs, tapes, and broadcasts that realize the full fidelity potential that is within our grasp.

----------------

Also see: