Like Rip Van Winkle, returning, he found the world changed.

by DON HECKMAN Link |

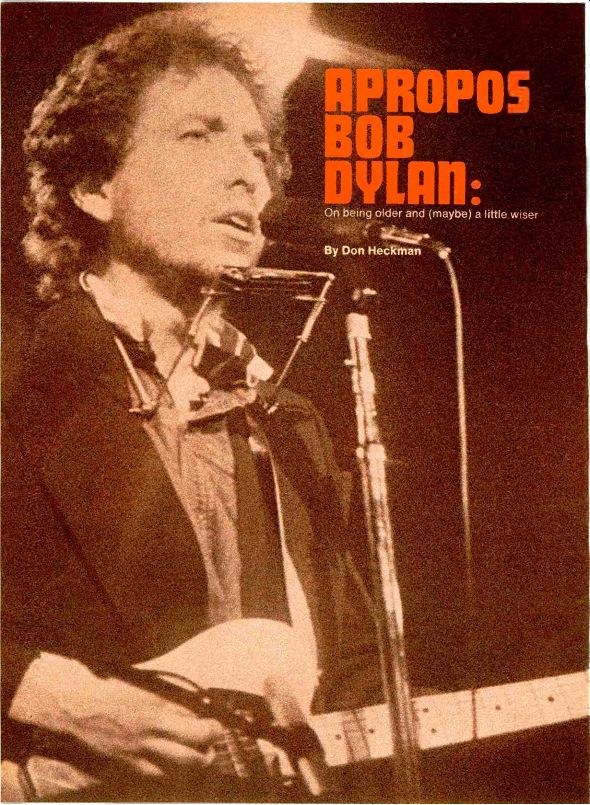

APROPOS BOB DYLAN: On being older and (maybe) a little wiser.

HE came on stage with what was almost certainly a self-conscious disdain for the drama of it all: Bob Dylan--idol of a generation, voice of a movement, enigmatic puzzle at the core of the riddle that was the great Youth Movement of the Sixties-had returned for a nationwide tour after years of retirement and a few sporadic surprise appearances.

A bit aging at thirty-three, Dylan was otherwise little different in appearance from the casually rum pled young man who helped turn the pop-music world around in the halcyon days of the early Six ties. Still boyish, still just a bit vulnerable-looking, with eyes as eerily penetrating as ever, his very presence stirred memories of long-dissipated energies. But the puzzle no longer seemed so enigmatic.

For one thing, the songs simply failed to achieve their old impact. Is it going too far to say that Blow in' in the Wind and Like a Rolling Stone, once the initial rush of the feelings they aroused was past, sounded like nothing more than pleasant nostalgia? The thought will, no doubt, be blasphemy to many readers, but the aura of passivity, so rare a feeling to experience around Dylan, was too palpable to ignore. This 1974 Bob Dylan would send no one to the barricades, would provide no anthems for the Revolution.

No, what we heard and saw in the 1974 Dylan tour was evidence of the ascendency of a performer, confirmation of the disappearance of a proselytizer. It was, without question, the strongest performance I have ever heard from Dylan in more than ten years of listening to him in concert and on recordings. His voice was powerful and direct, the pliable instrument of interpretation that is the hall mark of a solid professional. The spoken/sung in flections that were the expressive limits of his earlier style were expanded to an emotional and musical gamut that ranged from guttural shouts to sweetest lyricism. Yet one wonders if the mere achievement of professional stature as a performer is what Dylan intended.

He choose to return to his public at a time when the country has been flailing about, desperately looking for functional idols and finding only crumbling relics of the past. Frank Sinatra returned too, looking and sounding more like a re-run than a renewal. And even Muhammed Ali's solid performance against Joe Frazier in Madison Square Gar den two nights before the arrival of Dylan had about it the sad and yielding slackness of aging muscles being pushed to their limits.

Strange and aimlessly restless times. Ten years after the death of John F. Kennedy and the first wave of Beatles madness, twenty years after the wiggle-hipped arrival of Elvis Presley smack in the middle of the McCarthy era, uncertainty, confusion, and suspicion were once again blowin' in the wind. And so, when the momentous announcement came that Bob Dylan would tour the country for the first time in ten years (and release a new recording to boot), it was understandable that a flash of expectancy would dart through the minds of those who once thought that the urgings of one itinerant troubadour could alter all our lives. We know better now, of course-those of us who were Dylan's con temporaries. We have been to too many peace marches and civil-rights demonstrations (almost archaic words these days) to expect mere songs to do that. But Dylan did serve a purpose, producing the music that helped create the consciousness we needed, that served as a rallying cry for a generation that thought, yes, it could change the world. And now we know that public awareness alone, even public anger, as Watergate is teaching even the most optimistic, can have only painfully gradual effects upon the status quo.

But the fact that we couldn't directly change things, the fact that it was nearly four years after many of us had had our heads busted in Chicago before the concept of "peace with honor" was finally served by a withdrawal from Viet Nam, in no way minimized Dylan's importance. In all the rush of music and words that came pouring out of the brilliant flood of pop performers who arrived in the middle and late Sixties, Dylan's voice was the most persistent, the most direct, and--despite the fact that he could never be accused of having been a Top-40 act-the most influential. In the finest tradition of the artist-philosopher, Dylan's words mobilized us, made us not only aware of what was happening in the world around us, but also aware of ourselves as something more than miniature replicas of the "adults" young people are tacitly expected to emulate.

No one else came close. Musical tracts here and there from the Jefferson Airplane, Graham Nash, Neil Young, and others had a certain impact. For at least a year or two it was virtually de rigueur to include some sort of "protest" song on every record album (and, too, there were the slightly different consciousness-raising efforts of Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield, and Isaac Hayes). But ultimately the major impact came from Dylan and from performers like Joan Baez and Peter, Paul and Mary who helped expose Dylan's songs to a larger audience.

Dylan was perhaps the first American popular musician to successfully use a "naïve" form of expression, as classicists like to refer to it, as a mass-media vehicle for cultural and social consciousness-raising. The blues, "folk" music, even jazz, in its own nonverbal way, had been the languages used by blacks, blue-collar workers, and geographically or economically isolated subgroups to vent their anger, to express their frustrations.

With the enormous expansion of the middle class that took place in the mid-Fifties and Sixties, there was a corollary expansion in the demographic importance of young people (a result of the post-World War II "baby boom"). For them, Dylan was the right voice at the right time; he said the right things in the right language for a segment of the population whose parents had just begun to achieve the material rewards that always had been part of the fanciful promise of America. But the oppression of blacks, the growing dominance of a white, middle-class, male-dominated society, and the looming specter of the Indochina War twisted the material accomplishments of the Fifties into the chauvinistic posturing of the Sixties. Dylan may have been good, but he also had the benefit of this unique confluence of historical and social currents--and, of course, of that marvelous machine, the phonograph, as well. And one wonders how many of the people who detested everything Dylan stood for in the early Sixties might not, today, in the midst of high-level government hanky-panky, energy crises, and a general souring of the American dream, find just a little sense in his words.

In retrospect, Dylan's greatest creative surge, the almost magical burst of energy that was so classic an expression of those ideas whose time had come, peaked in his earliest albums, at the time when he seemed concerned with reflecting the universalities of the world around him. Even his most fervent supporters were, at the very least, surprised by his return to acoustic music in "John Wesley Harding" and by the sweetly romantic sentiments (and crooning vocal quality) of "Nashville Skyline." Some observers wondered whether Dylan's near-disastrous 1966 motorcycle accident did not have a psychological as well as a physical impact. His quiet family life, the fathering of five children, a trip to Israel, and an honorary degree from Princeton only seemed to underline the blandness that crept into the Dylan recordings of the last few years. The original energy may still have been there in some form, but, with few genuine live performances and only the records to guide us, it was understandable that Dylan's survival as a creative force became moot.

His appearance at the Bangladesh concert in mid-1971 was, at best, an enigmatic, even gratuitous event, more significant as a "happening" than for its musical consequence.

We heard Dylan in his 1974 "return," then, with mixed emotions. Like many other pop-rock stars, he can of course sell out major halls almost instantly, and tickets for his tour were the most difficult to obtain since the last time the Rolling Stones went cross-country. But the very act of returning to pub lic performing had the effect of freezing Dylan into a posture he would never have found acceptable ten years ago. His programs, with the exception of one or two innocuous songs from his current (also in nocuous) album, consisted of past hits: The Times They Are A-Changin'; Gates of Eden; Just Like a Woman; Lay, Lady, Lay; Just Like Tom Thumb Blues; It Ain't Me Babe; Ballad of a Thin Man; and so on. They were all songs with special memories attached, poetic fragments of--still--astonishingly moving imagery, but they were only memories, not universal and timeless rallying cries.

So, quite simply and quite pointedly, Bob Dylan still has the power to reach us, even to touch us, but he no longer has the ability-or perhaps even the desire-to get us up off our butts. That was, at one time, a significant power indeed. But looking around at the audience in Madison Square Garden, I could not help but notice that it was, for the most part, an older crowd than one usually sees at pop-music concerts, that some of the listeners seemed, like Dylan, a bit self-conscious in their tattered jeans and old battle jackets. There was something of the quality of a reunion of old army buddies, their uniforms dragged out of mothballs to help revive old and fleeting memories. And up on stage, accompanied-appropriately enough-by the Band, a group that had toured with him through so many campaigns, was the inspirational leader, recalling for us, in oddly déjà vu fashion, the thoughts and ideas we all knew so well that we could sing along in unison.

General MacArthur's classic recollection of the fate of old soldiers was, sadly, in mind as Dylan closed the concert with what was once thought to be the ultimate youth anthem, Like a Rolling Stone.

When the audience lit matches and cigarette lighters in quiet tribute, one could truly appreciate what Dylan had once meant--so short a time ago--to all of us. But one could also wonder whether the Dylan of 1974 had not ironically become his archetypical Mr. Jones of Ballad of a Thin Man, whether he knows any more than the rest of us what is really happening.

Don Heckman, formerly a jazz reviewer for this magazine, is a professional musician and free-lance record producer. He plays the alto saxophone and as a composer is active in TV.

----------

Also see:

CHOOSING SIDES--The German Tradition. IRVING KOLODIN