Reviewed

by RICHARD FREED, DAVID HALL, GEORGE JELLINEK, IGOR KIPNIS, PAUL KRESH,

ERIC SALZMAN

D'ALBERT: Piano Concerto No. 2, in E Major, Op. 12. REINECKE: Piano Concerto No. 1, in F-sharp Minor, Op. 72. Michael Ponti (piano); Orchestra of Radio Luxembourg, Pierre Cao cond. CANDIDE CE 31078 $3.98.

Performance: Flashy and unmemorable

Recording: Very good

Eugen d'Albert (1864-1932) was born in Scotland, but he considered himself a Ger man, and it was in Germany after his studies with Liszt that he made his reputation both as pianist and composer. Liszt evidently thought very highly of him, and many considered him the proper heir to Liszt's throne. A little man in stature, d'Albert more than made up for it by his personality (testy) and his approach to the keyboard (titanic); among his six wives, incidentally, was another pianistic giant, Teresa Carrell°. He wrote twenty operas, of which only a couple (Tiefland and to a lesser extent Die Toten Augen) are even dimly remembered in our era, but there can be no denying that he was vastly admired in his own day, though perhaps more as a performer than as composer. The one-movement Second Piano Concerto is Lisztian in form and influence-in the use of thematic transformation, for example--but, despite some likable lyrical sections, it is overall a very unmemorable piece. Perhaps this is because of its sprawling themes and empty pomposity in the noisier parts.

--

Explanation of symbols:

= reel-to-reel stereo tape

= eight-track stereo cartridge

= stereo cassette

= quadraphonic disc

= reel-to-reel quadraphonic tape eight-track quadraphonic tape

= quadraphonic cassette

Monophonic recordings are indicated by the symbol

The first listing is the one reviewed: other formats, if available, follow it.

------------------

A less flamboyant personality, Carl Reinecke (1824-1910) was one of the most distinguished musicians of his time; he worked as pianist, conductor, teacher. and composer in Denmark, Cologne, Barmen, Breslau, and finally Leipzig, where he directed the famous Gewandhaus concerts between 1860 and 1895. His output, which includes four piano concertos as well as operas, symphonies, and a vast quantity of keyboard, chamber, and pedagogical pieces, is usually described as being very well made and at least partly influenced by his admiration for Mendelssohn. On records, he has been represented by concertos for flute, harp, and piano (the First Piano Concerto was also issued recently on Genesis GS 1034 with Gerald Robbins as soloist), a Kindersinfonie for toy instruments, and some cadenzas. As Richard Freed notes in his excellent program annotations for this Candide recording, it is the slow movement of the First Piano Concerto that is the most impressive part of Reinecke's piece: as for the rest, though it does not bluster a la d'Albert. I am afraid that it is not much more memorable thematically. Perhaps my lack of enthusiasm owes something to the quality of these performances, for the orchestral accompaniment is adequate but routine, and the soloist, though lacking absolutely nothing in brilliance and virtuosity, simply does not provide sufficient pianistic color, elegance, and Romantic rhetoric to enable these two concertos to come back to life. /.K.

-------- BENJAMIN LUXON A performance to delight the composer's

heart

ALWYN: Mirages. Benjamin Luxon ( bari tone); David Willison (piano). Divertimento for Solo Flute; Naiades, Fantasy-Sonata for Flute and Harp. Christopher Hyde-Smith (flute); Marisa Robles (harp). MUSICAL HERI TAGE SOCIETY MHS 1742 $3.50 (plus 75's handling charge from the Musical Heritage Society, Inc., 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performance: Excellent

Recording: Very good

William Alwyn (born 1905) has enjoyed a solid reputation in England for some time, but his music seems to be only rarely exported. On another recent MHS disc (like this one, de rived from the Lyrita catalog), he conducts the London Philharmonic himself in four of his Elizabethan Dances (MHS 1672, a collection of English contemporary music reviewed here last June). This new record is devoted entirely to his works, however, and it is a very attractive assortment.

The song cycle Mirages, composed in 1970, is at least as striking for Alwyn's marvelous texts as for his imaginative music. In two of the six songs, Undine and Honey suckle, he conveys the most touching sentiment without the slightest self-consciousness or literary affectation-and without that pretentious false humility that is worse than all other offenses. The words are real, human, convincing, and, in conjunction with the mu sic, genuinely poetic. The concluding Portrait in a Mirror is both grim and poignant, but leavened by the subtle humor present through out the cycle. William Mann says in his notes that Alwyn wrote the music for David Willison: the aural evidence is strong that he wrote it for Luxon as well- whether he knew it or not.

Naiades, an alluring thirteen-minute work in a single movement, was also written for the performers who play it here. There is, as Mann observes, a certain connection between this work and Mirages, in that the first song in the cycle is Undine. The Divertimento for Solo Flute antedates the other two works on the disc by more than thirty years, and, again according to Mann, it was in this composition of 1939 that Alwyn first found his own voice; its four movements are so rich in melodic invention and rhythmic activity that the listener may have to keep reminding himself that it is a solo flute he is listening to. Christopher Hyde-Smith, whose name up to now has been less well-known here than that of his wife (Marisa Robles), is an absolutely first-rate flutist, and one from whom we shall surely be hearing a good deal more.

This is attractive, well-crafted, readily accessible music, all of it, and all performed in a manner to delight any composer's heart-and any listener's, for that matter. Clean, full bodied sound, too. R.F.

ARENSKY: Variations, on a Theme of Tchaikovsky (see DVORAK) BARTOK: Divertimento for String Orchestra; Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta. Cologne Philharmonic Orchestra. Gunter Wand cond. EVEREST 3355 $4.98.

Performance: Decent, unexciting

Recording: Clear, dry

Gunter Wand is known here largely for his recorded performances of early music, but these are decent, idiomatic, unexciting performances of chamber-orchestra Bartok. I doubt that they are recent performances. They were originally recorded for and by the Club Francais du Disque- more than a decade ago, I would guess (Leonardo Nierman, whose art is reproduced on the jacket cover, is de scribed as having work "on display in the collection of the President and Mrs. John F. Kennedy in the White House"). The recording- or its transfer--is low in level, rather close, and rather dry. The orchestra-apparently the Gurzenich Orchestra of Cologne plays cleanly, although the energy level does not seem very high. E.S.

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 7, in A Major, Op. 92. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Colin Davis cond. ANGEL S-37027 $5.98.

Performance: Good

Recording: Generally good

As he demonstrated in his excellent recorded performance of the Eroica for Philips, Colin Davis need take second place to no one when it comes to honest, powerful, and intensely musical readings of the Beethoven symphonies. His Angel recording of the Seventh shows close kinship with the incomparable 1936 version by Toscanini and the New York Philharmonic, but with a shade less drive and a somewhat more refined lyrical quality. Un like Toscanini, Davis and the Royal Phil harmonic do relax the tempo in the scherzo for the chorale-like trio.

The recording as such is generally good in terms of balance and tonal warmth, but it suffers at times from the oddly diffuse quality that has afflicted many of the British-originated Angel orchestral discs I have heard of late.

The Beethoven finale especially is the poorer for this, inasmuch as the timpani sound comes through as an amorphous blur rather than clearly defined tone. D.H.

BEREZOWSKY: Fantasy for 9 (see Collections-Modern Pianos) BOLCOM: Frescoes. Bruce and harmonium); Pierette Le Two Pianos, Op. Music for Two Mather (piano Page (piano and harpsichord). NONESUCH H-71297 $3.98.

Performance: Authoritative

Recording: Outstanding

In his program note for Frescoes, William Bolcom describes it as music composed (in 1971) out of a need to "hew the air," an "apocalyptic" work, derived in part from an experimental piece he had written a decade earlier and inspired by such stimuli as "jumbled half-remembrances of frescoes at the Campo Santo in Pisa . . . , friezes at Pompe ii, bits of Virgil and Milton, a cantata by one of the earlier Bachs, and a frightening brush with the Abyss. . . ." The work is in two parts: War in Heaven is the battle be tween Michael and Lucifer, as depicted in Christoph Bach's Es erhub sich ein Streit, in Milton's Paradise Lost, and in the New Testament Book of Revelations: The Caves of Orcus is a mythological netherworld, described in lines from the Aeneid. Whether the music actually summons up these images or not, it is a pair of fascinating sonic journeys, into a region not unlike the domain of Bolcom's earlier Black Host, and the "apocalyptic" character is pretty unmistakable. Mather and Le Page, for whom Bolcom wrote Frescoes, give a demoniacally authoritative performance. One side of thirteen minutes and another of fifteen might seem to add up to short weight for a whole disc, but this spread may have been necessary to achieve the really outstanding sonic realism of the recording. R.F.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

BRAHMS: Ballade in G Minor, Op. 118, No. 3. Intermezzos: A Minor, Op. 76, No. 7; B-fiat Minor, Op. 117, No. 2; A Minor, Op. 118, No. 1; B Minor, Op. 119, No. 1; C Major, Op. 119,

----------------------------

---Scene from the 20th Century Fox production The Day the Earth Stood Still

The Sound of Herrmann-- You've seen the movie; now hear the score

Reviewed by Irving Kolodin

FED up with everything around you? Anxious to get away from it all? And beset by the financial crunch? My best ad vice is recourse to the transporting music by Bernard Herrmann contained in a new release from London's Phase 4 series. Here you can Journey to the Center of the Earth, experience The Day the Earth Stood Still, participate in The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, and brave the brave new world of Fahrenheit 451 through Herrmann's arrangement into suites of the music he com posed for the soundtracks of these films.

The only one of the films known to me by sight is The Day the Earth Stood Still, and I was so absorbed in the action of it that I ignored the music. As any film composer will tell you, that is the highest possible praise for his product. Heard by itself, the music is not at all ignorable. It is devilishly clever in its use of electronic strings amid an assemblage of more conventional instruments.

The opening of Journey to the Center of the Earth is also promising. On the way, however, Herrmann apparently took a side trip into the Niebelheim, when Alberich was doing his Fafner trick. When you've heard one serpent, you've heard them all. Of the four scores, Herrmann's evocation of Baghdad and vicinity is the most consistently interesting in material as well as treatment. For the best results, I suggest listening in a dark room at about movie-theater temperature, thus allowing the mind to make pictures. It won't be doing much else any way. Engineer Arthur Lilley deserves high praise for those groaning lows in Journey.

HERRMANN: Suites from the Film Scores. Journey to the Center of the Earth; The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad; The Day the Earth Stood Still; Fahrenheit 451. Nation al Philharmonic Orchestra, Bernard Herrmann cond. LONDON SP 44207 $6.98.

----------------------

No. 3. Rhapsodies: B Minor, Op. 79, No. 1; G Minor, Op. 79, No. 2; E-flat Major, Op. 119, No. 4. Morton Estrin (piano). CONNOISSEUR SOCIETY CSQ 2060 $6.98.

Performance: Impassioned

Recording: First-rate sound; minor disc problems

Morton Estrin's musicianship and keyboard prowess, demonstrated in his recordings of Scriabin and Rachmaninoff, continue to impress me with his sensitivity and communicative power in the Romantic repertoire. His Brahms program is a richly varied one, covering the gamut of that master's rhetoric from the thunder and lightning .of the Rhapsodies and the G Minor Ballade, through the passion of the Op. 118, No. 1 Intermezzo and the delicious play of the C Major Intermezzo, to the bare wisps of sound embodied in the one in B Minor, Op. 119, No. 1.

In fact, I find everything about Mr. Estrin's playing and the recording of it richly satisfying. There is vigor aplenty in the big pieces, carefully gauged variety of color and dynamic in the small ones, tasteful rubato wholly free of mere fussiness, and a disciplined sense of the musical architecture of each piece that precludes any merely ruminative readings.

Straight stereo playback of the Estrin disc reveals the full-bodied and clean sound to which Connoisseur Society has accustomed us over the years in the best of its many fine piano records, and bringing the quadraphonic circuitry into play effectively enlarges the sonic ambiance with no trace of exaggeration or gimmickry. Except for a slightly off-center pressing on side two and somewhat noisy surfaces, this disc is an absolutely first-rate job, musically and sonically.-D.H.

BRAHMS: Intermezzos (see FRANCK) BRUCKNER: Mass No. 2, in E Minor. Schutz Choir of London; Philip Jones Wind Ensemble, Roger Norrington cond. ARGO ZRG 710 $6.98.

Performance: A model of clarity

Recording: Crystal clear

BRUCKNER: Mass No. 2, in E Minor. Gachinger Kantorei; Spandauer Kantorei; Bach Collegium Wind Ensemble, Helmuth Rilling cond. MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1801 $3.50 (plus 754 shipping, from Musical Heritage Society, Inc., 1991 Broad way, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performance: Warm-hued

Recording: Ecclesiastical ambiance

For those who find Anton Bruckner's Cyclopean symphonies too much to take, his neo Renaissance E Minor Mass-composed about the same time as the First Symphony is just the thing to reveal the Austrian master's way with line and polyphony minus the trappings of Romantic rhetoric. For this work, as distinguished from the full-orchestra-accompanied D Minor and F Minor Masses, calls for the eight-part choir to be backed only by a wind band of oboes, clarinets, and bassoons in pairs, plus four horns, a pair of trumpets, and three trombones. Yet, for all the neo-Palestrina aspects of the music, Bruckner is by no means averse to expressive harmonic evocation where the text demands, as in the majestic Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris of the Kyrie, or in the awe-struck Et incur-flatus and the quietly poignant Crucifixus.

Some additional high points are the splendid

Amen fugue that concludes the Gloria and the gorgeous canonically textured Sanctus.

Close to a dozen recordings of this Mass have been in and out of the catalogs since the middle 1930's. These two performances are the first stereo versions I have heard, how ever, and, oddly enough, three out of the four currently listed in Schwann have been issued within the past year. Roger Norrington's and Helmuth Rilling's performances are in sharp contrast to one another. Norrington's is as crisp and clear as one would expect of a performance of the Stravinsky Mass (also wind-band accompanied), and the music took on an entirely new perspective for me as heard in this relatively close-miked, non-ecclesiastical acoustic. The biggest gain is in clarity of texture throughout the vocal and instrumental, spectrum, permitting one to hear things in the music that are usually--because of the church acoustic prevalent in many of the earlier recordings--inaudible. The bassoon line in the opening of the Gloria is one instance that comes immediately to mind. The music gains in interest simply by becoming more audible.

Taken as a whole, the Norrington reading is crisp, utterly clean in line, dead on-center in intonation, and perhaps a bit lacking in body in the bass.

If you want the cathedral atmosphere and Romantic treatment, the Helmuth Rilling re cording will fill the bill nicely. His choir is no match for the London Schutz group in terms of intonational accuracy or precision of at tack, but the singing is wholly competent and warm-toned. The Argo issue includes no text, but the record is banded for each section of the Mass; the MHS record is not banded, but the package does include a full Latin-English text. -D.H.

CHOPIN: Barcarolle in F-sharp Major, Op. 60 (see FRANCK) CHOPIN: Piano Sonata No. 3, in B Minor, Op. 58. LISZT: Piano Sonata in B Minor. Agustin Anievas (piano). ANGEL S-36784 $5.98.

Performance: Strong Liszt

Recording: Good piano sound

These are both respectable performances of ultra-Romantic B Minor music. If it had been up to me, I would have put Liszt first. Anie vas is somehow a bit more attuned to the outgoing qualities of the Liszt-even when Liszt is meditating or soliloquizing, he is doing so "in public." On the other hand, Chopin, even at his most outgoing, always seems to be engaged in some kind of inner dialogue, and it is this introspective quality that Anievas does not quite catch.

Don't get the impression that his playing is all outer show. Not at all. He makes a beautiful sound, and a lyric flow of sound is his strong point. He never makes a wrong move.

Everything is in perfect taste and proportion- nice Romantic pianism. E.S.

COPLAND: Appalachian Spring (see The Basic Repertoire, page 61)

CORELLI-GEMINIANI: Six Concerti Grossi, from Corelli's Trio Sonatas in G Major, Op. 1, No. 9; F Major, Op. 3, No. 1; B-flat Major, Op. 3, No. 3; B Minor, Op. 3, No. 4; F Minor, Op. 3, No. 9; A Minor, Op. 3, No. 10. String ensemble, James Bolle cond. MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1734 $3.50 (plus 75e handling charge from the Musical Heritage Society, 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performance: Commendable

Recording: Very good

Corelli's influence was very much felt in England in the early decades of the eighteenth century, as evidenced by the great numbers of concerti grossi published there during this period. Among them were pieces by such newly arrived foreigners as Francesco Geminiani (a Corelli pupil who came to London in 1714) and Veracini, imported music (often reprinted in England) by Vivaldi and Locatelli, and, of course, the works of native-born composers such as Avison and Festing. A vast number of music societies, mostly amateurs, subscribed to these new publications, and until Handel arrived on the scene the tendency on the part of many composers was to imitate Corelli. Geminiani, for instance, not only did this in his earlier original concertos but also transcribed as concertos a variety of Corelli's works, the Op. 5 violin sonatas as well as the six trio sonatas from Opp. 1 and 3 recorded here. These latter pieces appear to be very skillfully arranged, with Corelli's orig inal two violins plus cello continuo acting as the solo concertino against a more fully scored tutti of strings, thereby providing all the proper elements of the concerto grosso principle. The pieces themselves are splendid examples of Corelli, even in this concerted guise, and the playing by the thirteen-member ensemble (whether this is James Bolle's Musica Viva, the name of the group he has directed on previous discs, is not indicated) is on the whole very stylish if not always very polished. The music is given an excellent sense of direction, but there are, it must be admitted, some intonation problems as well as an occasional lack of precision. It would have made a delightful live concert, but for the permanence of a record, I think, the instrumental flaws wear less well. I.K.

DVORAK: Serenade for Strings in E Major, Op. 22. ARENSKY: Variations on a Theme of Tchaikovsky, Op. 35a. English Chamber Orchestra, Johannes Somary cond. VANGUARD VSQ-30011 $6.98.

Performance: Excellent Arensky

Recording: Very good

The Dvorak Serenade on this disc has never been issued before, but the Arensky has been available on Vanguard's Cardinal label in regular stereo format for some two years. Somary makes rather heavy going of the first two movements of the lovely Dyadic piece, but his touch lightens sufficiently to make the final three movements thoroughly enjoyable.

As for the charming Arensky Variations, both the modest size of the string group and Somary's fluent treatment of the music serve to make this performance, either in the quadraphonic or the original stereo issue, the best available. Vanguard's sonics are superbly clear and full-bodied, and a handsome semi-surround effect is achieved when the four-channel playback is brought into optimum perspective. D.H.

FALLA: Concerto for Harpsichord, Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Violin, and Cello; Psyche; El Retablo de Maese Pedro. Ana Higueras Aragon (soprano): Tomas Carera (tenor): Manuel Perez Bermudez (bass): Robert Veyron-Lacroix (harpsichord): instrumental ensemble, Charles Dutoit cond. MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1746 $3.50 (plus 754 handling charge from the Musical Heritage Society, Inc., 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performance All right

Recording: Not the best

None of these three performances is less than satisfactory in its own right, but all of them are really overwhelmed by the competition, and the sound itself, far below the usual standard from this source (Erato), is no help. The most that can be said for the new disc, I'm afraid, is that it serves to remind us of the uniquely appealing works themselves and calls attention to the matchless recordings of them available elsewhere: Ataulfo Argenta's Maese Pedro (London STS-15014): Rafael Puyana's Harpsichord Concerto, with Charles Mackerras conducting (Philips 6505 001): and Victoria de los Angeles' Psyche, with flutist Jean-Claude Gerard, harpist Annie Challan, and the Trio a Cordes Francais (Angel S-36716). R.F.

RECORDINGS OF SPECIAL MERIT

FAURE: Barcarolles Nos. 1-13 (complete). Jean Doyen (piano). MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1772 $3.50 (plus 754 shipping, from the Musical Heritage Society, Inc., 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

FAURE: Nocturnes Nos. 1-7 and 9-13; Bal lade, op. 19; Theme and Variations in C-sharp Minor, Op. 73. Jean Doyen (piano).

MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1770/1771 two discs $7.00 (plus 75¢ ship ping, from the Musical Heritage Society, Inc., 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performances: Irresistible

Recordings: Good

Faure's piano music has been all but impossible to come by on records except in "integral" offerings of all of it; it seems safe to assume that these discs represent the first installments in another such project, in which the missing Nocturne No. 8 will turn up as one of the Huit Pieces Breves, Op. 84.

As shown in the chronological chart in Harry Halbreich's excellent notes for the two-disc set, these works span virtually the whole of Faure's creative life, the little-known solo version of the Ballade having appeared some time before the familiar piano-and-orchestra version of 1881, the last of the barcarolles and nocturnes forty years later (three years before Faure's death). Jean Doyen's authority in this material and his obvious affection for it ensure that every one of these twenty-seven works is downright irresistible in its own right-in addition to their collective value in filling in the picture of a still too-little-known composer whose musical image grows ever more attrac tive as it becomes more nearly complete. The piano sound is very good, with only occasion al pre-echo and all of that well below the nuisance level. R.F.

FRANCK: Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue.

BRAHMS: Intermezzo in A Major, Op. 118, No. 2; Intermezzo in B-flat Minor, Op. 117, No. 2. CHOPIN: Barcarolle in F-sharp Major, Op. 60. Ivan Moravec (piano).

CONNOISSEUR SOCIETY CS 2062 $6.98.

Performance: Broad-scaled

Recording: Very fine

FRANCK: Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue; Pre- lude, Aria, and Finale; Prelude, Fugue, and Variation, op. 18; Danse Lente; Les Plaintes d'une Poupee; Canon and Fugue in C Major. Jorg Demus (piano). MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1152 $3.50 (plus 75e shipping, from Musical Heritage Society, Inc., 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performance Excellent

Recording: Mostly excellent

Cesar Franck's indisputable masterpiece for piano, the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue, has in the past been a handsome performance vehicle for such major keyboard lions as Cortot, Petri, Rubinstein, and Richter. Of late, though, it seems to have fallen out of favor in the concert hall, despite the fact that it is not only highly pianistic in idiom, but one of the most successful of all creative efforts to combine Baroque polyphony with Romantic rhetoric.

The Connoisseur Society performance with Ivan Moravec is a remastering from the 1962 taping originally issued as a 12-inch disc to be played at the 45-rpm speed. The quality of the piano sound was exceptional then in its full ness of tonal and dynamic range, and there is no perceptible loss of quality in this 1974 transfer to the slower speed. My review pressing was wretchedly off-center, however, with dire consequences for stability of pitch.

Moravec's performance itself is luxuriant in dynamics and coloration and expansive in its prevailingly broad tempo. The same broad, almost ruminative, treatment marks his readings of the two Brahms intermezzos, here is sued for the first time. In the Chopin Barca rolle, Moravec's rich-toned playing, with re cording to match, is wholly appropriate to that gorgeous masterpiece of Chopin's last years.

This same performance may be heard on Moravec's Chopin disc issued by Connoisseur Society in 1969.

Turning to Jorg Demus' Musical Heritage Society all-Franck program, I must confess that I find his tauter treatment of the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue more to my taste than Moravec's. The music is quite rich enough in its essential harmonic texture, and a some what leaner interpretation does it no harm whatever.

Demus is no stranger to the Franck piano repertoire, having recorded both the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue and its somewhat later and much less familiar-companion piece, the Prelude, Aria, and Finale, for a monophonic Westminster release back in the 1950's. I find the latter piece a good deal less successful pianistically and musically. The Aria section is altogether lovely-prime Franck by any standards-but the opening section, to my ears, verges on the banal, and the close simply does not build up to a convincing sense of inevitable resolution comparable to that in the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue. The Danse Lente and the little doll piece are endowed with a certain charm, but they seem irrelevant alongside the two major piano works. Something of a fascinating surprise is the little Canon and Fugue, for which the sleeve notes give no background information: presumably the music comes from one of Franck's two sets of harmonium pieces-either L'Or ganiste from his last years or the posthumously published series of forty-four pieces from 1858-1863. The Prelude, Fugue, and Variation pre-dates by more than a decade the masterpieces of the later Franck, being the third of Six Pieces pour Grande Orgue. This is altogether lovely and beautifully made music; it is most effective as an organ work, but it does work reasonably well, if not very idiomatically, on the piano.

The Demus performances are of uniform excellence, musically and technically, but the recording is somewhat variable. It has good body and presence throughout except in much of the Prelude, Aria, and Finale, where about halfway into the opening section I get the feeling that the microphone has been moved further away from the piano. D.H.

-------------------

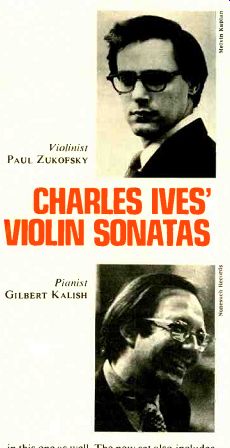

CHARLES IVES' VIOLIN SONATAS

Violinist PAUL ZUKOFSKY

Pianist GILBERT KALISH

CHARLES IVES' violin sonatas were among the earliest of his works to be recorded, and separate recordings of them are frequently released- Sonata No. 2, for example, has been recorded in whole or in part seven times. Oddly enough, though, until now there have been only two integral recordings of all four sonatas, neither of them in stereo. The first one was recorded in 1955 by Rafael Druian and John Simms for Mercury (I was the producer) and was avail able for a time on a Philips World Series reissue. The second mono set, still available, was recorded in 1964 by Paul Zukofsky and Gilbert Kalish for Folkways. Now, in Ives' centennial year, Nonesuch has released another integral set of the sonatas, in stereo, and Zukofsky and Kalish are the performers in this one as well. The new set also includes a separate Largo, recorded here for the first time in Zukofsky's violin-piano edition.

The sonatas had their beginnings rather close to each other in time (1903-1906), but they reached final form over a considerably longer period (1908-1916). Like Bach and Handel, among others, Ives often used his materials more than once, and much of the musical substance of the sonatas appeared in other guises both before and after it was used in the sonatas themselves. Origins in some instances can be traced to early organ pieces or ragtime experiments. A large part of the material in the first two sonatas was salvaged and revised from a "Pre-First" Violin Sonata, while the Largo, written some time around 1901, began life as part of the Pre-First and was later revised for piano, clarinet, and violin, in which form it has been recorded no less than four times. The hymn-tune themes from the first movement of Sonata No. 2 and from the third movements of Sonatas Nos. 1 and 4 were also used by Ives in song treatments.

All together, the violin sonatas make an ideal introduction to Ives in his populist aspect-that is, as the "re-composer" and fantasist of hymn tunes, community songs, and fiddle pieces popular in and around Danbury, Connecticut, at the turn of the century. All but two of the thirteen movements in the Nonesuch set stem from these sources, which are accorded extraordinarily original and poetic transmutations, some of them relatively straightforward (as in the Fourth Sonata), others partaking of a phantasmagoric density reminiscent of the Night-town episodes of James Joyce's Ulysses (the In the Barn second movement of Sonata No. 2). Needless to say, the demands this music makes on the performers in terms of rhythmic acuity, sensitivity to dynamics, and subtleties of harmonic coloration go far beyond those of the standard violin-and-piano repertoire. But the results-especially what is achieved in this recording by Messrs. Zukofsky and Kalish--are certainly worth the effort.

Those who happen to own the earlier Druian-Simms recording of the sonatas will find the Zukofsky-Kalish one markedly different in performance style and at times in musical substance. Zukofsky and Kalish had access to the manuscript sources of the Ives Collection at Yale prior to both of their recordings, but, since the Collection had not yet been established in 1955, Druian and Simms did not; therefore, the earliest of the three integral recordings was done from the music as published, while Zukofsky and Kalish were able to incorporate into both their readings corrections and additions that presumably will appear one day when a critical published edition of Ives' music be comes a reality. Most striking of these additions is the tone-cluster "drum music" that enhances further the fantastical effect of the closing pages of In the Barn.

As for performance style, Druian and Simms stressed the music's volatility and rhythmic pulse, while Zukofsky and Kalish adopt a decidedly more ruminative and poetic approach--most noticeable in the First Sonata, which comes out as quite a different piece in their reading than in the earlier version. Another striking difference arises from Zukofsky's predominantly vibrato-less playing, which may not be to everyone's taste but certainly adds yet an other coloristic dimension to his interpretations. I find the pianism of Gilbert Kalish beyond criticism, impressive not only for his digital and rhythmic virtuosity, but most especially for his handling of subtle echo and harmonic effects, as in the finale of the Third Sonata.

Apart from what to my ears is a decided over-balance of piano at the expense of the violin line in the first part of the slow movement of the First Sonata, the sonic realization of the music on these Nonesuch discs is altogether superb. David Hall

IVES: Sonatas for Violin and Piano: No. 1 (1903-1908); No. 2 (1902-1910); No. 3 (1905-1914); No. 4 ("Children's Day at the Camp Meeting," 1905-1915). Largo (ca. 1901, ed. Zukofsky). Paul Zukofsky (violin): Gilbert Kalish (piano). NONESUCH H B 73025 two discs $7.96.

-----------------

G. GABRIELI: Sacred Symphonies. Magnifi cat; O Domine Jesu Christer Hodie Christus natus est; Hoc tegitur; Sancta et immaculata virginitas; Angelus Domini Descendit; Nunc dimittis; Jam non dicam vos servos; Miseri cordias Domini; Jubilate Deo; Regina coeli; O Jesu mi dulcissime; Ego sum qui sum. Wally Staempfli and Yvonne Perrin (sopranos); Claudine Perret, Magali Schwarz, and Denise Schwaar (altos); Olivier Dufour and Claude Traube (tenors); Philippe Huttenlocher and Daniel Reichel (basses); vocal ensemble, University Choir, and Lausanne Chamber Orchestra, Michel Corboz cond.

MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1749 $3.50 (plus 75c handling charge from the Musical Heritage Society, 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performance Very good

Recording: Very good but not ideal

Giovanni Gabrieli was second organist of S Marco in Venice (his uncle, Andrea, was first) in 1597, when he published forty-two motets in his first collection of Sacrae Symphoniae.

The present disc, entitled volume two, contains twelve pieces from this important collection, and the previously released first volume (MHS 1737) contains twelve more. Thus, al though a good deal of Gabrieli's sacred vocal music has been recorded from time to time, this is so far the greatest sampling from one published source.

The selection overall is a fine one and encompasses a considerable variety of styles and moods, from multi-choral antiphonal pieces extolling the birth of Christ (with excited alleluia refrains) to rather more meditative psalm settings. The solo and choral singing is on the whole good, as is the quality of the instrumental accompaniment (though there are no organ intonations): the style of singing, using mixed voices, sometimes veers a bit into the sentimental, but the parts are invariably clear. I do think, though, that the Columbia recording of Gabrieli motets (MS 7071), with the Gregg Smith Singers, Texas Boys' Choir, Edward Tarr Brass Ensemble, E. Power Biggs playing the organ, and Vittorio Negri conducting, conveys more effectively both the excitement of Gabrieli and the peculiarly intimate yet resonant acoustics of San Marco (the Columbia disc was actually recorded there) than the sonically more soggy, swollen sound of the MHS recording. MHS properly supplies the complete texts plus translations.

I.K.

HANDEL: Water Music; Royal Fireworks Music; Concerto in B-flat Major for Two Wind Choirs and Strings. La Grande Ecurie et La Chambre du Roy, Jean-Claude Malgoire cond. COLUMBIA MG 32813 $7.98.

Performance: Big Baroque band

Recording: Uneven

When I put this recording of the Royal Fire works on the turntable on a hot summer evening, real firecrackers started to go off out side. It was, in fact, the Fourth of July. Handel's fireworks had, of course, a slightly different origin, being the celebration music for the signing of the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle.

The piece, essentially scored for a big Baroque wind band, was first performed on April 27, 1749, in London's Green Park before a huge throng. The pyrotechnics were more spectacular than intended; the specially constructed pavilion, with its bas-relief of George II conferring peace on England, caught fire and started a panic in which several people were killed.

Under the circumstances we do not know how people reacted to the music, with its twelve bassoons, twenty-four oboes, nine horns, nine trumpets, timpani, and other drums. Modern attempts to reproduce the sound of this extraordinary ensemble generally sound terrible, and this one is no exception. La Grande Ecurie et La Chambre du Roy- literally "The Grand Stables and Chamber of the King"-was founded in 1966 by Jean-Claude Malgoire to perform early out door and indoor music on period instruments.

The sound is not only hair-raising but, owing largely to use of natural horns (without valves and entirely dependent, like bugles, on the player's lips, terribly out of tune. But just because natural horns and other old instruments are "naturally" out of tune does not mean they usually sounded that way in the eighteenth century. On the contrary, they were undoubtedly tuned "by ear"; each play er, with a lifetime of experience with his instrument, knew exactly how to make the nec essary adjustments, and the instruments would have sounded more "in tune" than modern equal-tempered ones! That this is outdoor music is no excuse at all. Truly in-tune playing carries a great deal of harmonic reinforcement and resonance; it will carry a great deal further than the kind of out-of-tune sound found here. In fact, the ensemble mix in this recording seems quite artificial, the result of a basically ineffective microphone balance, and the "natural" horns sound as though they had been recorded at a different time than all the rest.

Some of the above remarks apply to the Water Music. In spite of various legends, we know much less about the circumstances of this music than the other. In theory, it might be possible to justify Malgoire's extensive "arranging" of the music. This is not the Sir Hamilton Harty approach; the music has been reshuffled into several more-or-less inde pendent suites with added harpsichord solos, various changes of instrumentation, ornament ed repeats, and interpolated cadenzas. Nevertheless, I feel the arrangement is unidiomatic and displays little sensitivity to the music or style. There is a fundamental inequity be tween La Chambre du Roy, apparently a solo string ensemble, and the huge wind band, which is solved only through electronic mixing. The solo string playing is exquisite, but the wind playing is coarse and all the larger movements are heavy-handed. Almost none of the rearranging--re-sorting of the movements, multiple repeats with instrumental variants, etc.--are especially convincing and, in spite of the claims, none seem to correspond with Handel's own suggestions.

The Concerto in B-flat for two wind bands and strings is one of two or three such concertos by Handel. The first Allegro turns out to be Handel's own instrumental version of a chorus from Messiah, and one wonders where the rest was lifted from (Handel was a genius at plagiarizing himself and everyone else as well). It's good music though. Despite a certain affinity with the grand style of the outdoor pieces, this is still music for the chambre and, as such, is by far the best performed and re corded on the album.

I don't think anyone buys record albums for their liners, but mention should be made of Edward Sorel's amusing cover design as well as the excellent notes by STEREO REVIEW'S Robert S. Clark. E.S.

HAYDN: String Quartets, Op. 50, Nos. 1 and 2 (see Best of the Month, page 86) HELLER: Solitary Rambles, Op. 78; Valses Reveries, Op. 122; Nocturne, Op. 103; Tarantella in E Minor, Op. 53; Thirty-three Variations on a Theme of Beethoven, Op. 130. Ger hard Puchelt (piano). GENESIS GS 1043 $5.98.

Performance Steady

Recording. Serviceable

Not very long ago I described Stephen Heller as one of those composers remembered for one or two works (The Avalanche and a tarantella, if I recall correctly). I was challenged on this by someone who argued that there was still plenty of Heller piano music around.

Shortly thereafter I was prowling around in my mother's music collection--my secret source of information about Romantic kitsch and related goodies-and discovered whole volumes of Heller. My mother says that, in her day, it was mostly used as teaching material; nobody really played it in public any more. Well, here is the German pianist Ger hard Puchelt with a bouquet of Heller, not in concert, perhaps, but on a disc calculated to revive a bit of interest in the composer.

Heller was born in Budapest in 1813 and spent much of his life in Paris. Nevertheless, he was a confirmed German Romantic whose idol was Schumann. He rang up a high count of opus numbers exclusively devoted to piano music. Most of these are short poetic pieces gathered into sets with picturesque titles.

Schumann and Mendelssohn are always the models, but Heller carefully avoids the profundities and, yes, the difficulties of the greater men. His aim is always to please in the graceful, melancholy way that was much appreciated by bourgeois young ladies, their proud parents, and their ardent suitors. For this was Heller's public, and his music suited them perfectly. Alas, another generation demanded sterner stuff, and, except for a few old-fashioned piano teachers, nearly all of Heller's work passed into oblivion.

I think it is probably more fun to rescue the actual music, and, if you are able, to try some of it out yourself on the piano; on the whole, it is not very difficult to play and most of it is meant to while away the idle hours- it's not an unpleasant way of doing same. In lieu of that, however, Puchelt's sympathetic performances will reintroduce this minor master. At his best, he is genuinely engaging. And, in deed, sometimes- notably in his thirty-three variations on the theme of Beethoven's Thirty-two Variations--he rises to unaccustomed heights. Just for a moment or two, mind you, but fine moments these are. All in all, this is a record of unexpected pleasures. E.S.

D'INDY: Symphony on a French Mountain Air, Op. 25. Joela Jones (piano); Westphalian Symphony Orchestra, Paul Freeman cond.

POULENC: Aubade for Piano and Eighteen Instruments. Joela Jones (piano); London Symphony Orchestra, Paul Freeman cond. ORION ORS 74139 $6.98.

Performance: Interesting pianist

Recording: Generally good

I'm glad to find Joela Jones recording. At her 1965 New York debut in her teens, in a Lewisohn Stadium concert with Arthur Fiedler conducting, sudden summer rains cut her off in two or three valiant attempts to get through the MacDowell Second Concerto, and she never did get to finish what had all the promise of a superior performance. In the safety of the recording studio, she has completed two very impressive performances of highly at tractive French works for piano and orchestra, quite enough to make one eager to hear her again, even if not- ironically-eager to buy this particular record. The Westphalian Symphony has shaped up quite a bit over the last few years, and nothing need be said in support of the London Symphony's virtuoso players, but the orchestral contributions are rather conspicuously short on the subtlety and nuance these works call for. In the D'Indy, which is by no means a mere piano piece with accompaniment, but a symphony with piano obbligato, one wants a first-rate ensemble and the seeming spontaneity that comes only with rock-solid assurance. This version would be welcome enough in the absence of any others, but it is hardly competitive, musically or economically, with the recordings by Casadesus/Ormandy (Odyssey Y-31274) and Henriot-Schweitzer/Munch (Victrola VICS 1060), both blessed also with good sound and priced at less than half the Orion "list." Miss Jones makes a good showing, but the package as a whole is simply outclassed by the formidable competition. R.F.

ISAAC: Missa Carminum. SENEL: Missa Per Signum Crucis. Capella Antigua of Munich, Konrad Ruhland cond.

MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1777 $3.50 (plus 75c handling charge from the Musical Heritage Society, 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performance: Straightforward

Recording: Excellent

Heinrich Isaac (c. 1450-1517) spent most of his life working for the Medici family and Emperor Maximilian, living primarily in Florence and Vienna, where he wrote a considerable number of sacred works (some twenty three Masses as well as many motets) and such secular music as his famous Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen. Ludwig Senfl (c. 1490 1543) was Isaac's pupil and assistant, and he, too, worked for Maximilian, singing in the court chapel and later, after his teacher's death, taking over as court composer. He ended his life in Munich, where he worked in the Bavarian court chapel. Motets, seven Masses, and a considerable number of songs are among his output.

Both Isaac's Missa Carminum, which is based not on plainsong but on a variety of secular songs, and Senfl's Missa Super Per Signum Crucis, written for the consecration of an altar in 1530 and based melodically on a now lost motet, are splendid works and de serve to be better known, but the performances here could have done with greater expressiveness. Much of the singing, and this is perhaps most apparent in the Isaac Mass, is too much on one plane dynamically, in pacing and tempo, and in expressivity: one doesn't often feel that the singers take their words to heart (just another church job?), although the Et incarnatus est in the Senfl Mass is a notable exception. This is a bit surprising, for the Capella Antigua of Munich has done some notable recording of this kind of repertoire in the past. There is more give at cadences in the Nonesuch recording of the Isaac Missa Carminum (H-71084) by the Niedersachsischer Singkreis of Hannover, whose diction is also better. The latter, incidentally, is an a cappella performance by a men's and boys' choir and is really quite lovely. The Capella Antigua uses instruments (balanced much too loudly, although I cannot deny their colorfulness) and a mixed group. Texts are included, and the recorded sound is forward but atmospheric.

I. K .

KABALEVSKY: Piano Concerto No. 3, Op. 50 (see RUBINSTEIN)

KODALY: Marosszik Dances; Nine Pieces for Piano, Op. 3; Valsette; Meditation sur un Motif de Claude Debussy; Seven Pieces for Piano, Op. 11. Gyorgy Sandor (piano). CANDIDE CE 31077 $3.98.

Performance: Highly idiomatic

Recording: Good

Unlike Bartok, Kodaly wrote very little piano music, and this anthology contains all his major works in the medium (but it is not, as advertised. complete, omitting two sets of children's pieces). The earliest influence is that of Debussy, overtly reflected in the Meditation on a theme from Pellet's. Debussy was a revelation for many European composers because he opened their ears to the possibilities of using ethnic and other non-tonal material in a way that escaped the confines of the Italian-German harmonic system that had so thoroughly dominated European music in the nineteenth century. The immediate result was a period of experimentation parallel to but quite distinct from the new music coming out of Paris and Vienna.

Kodaly's Op. 3, written in 1909, is, along with certain contemporary works of Bartok, very nearly as "advanced" as anything being done at the time. The inventive and fascinating little pieces use fragments of folk-like material, combining them with various harmonic and rhythmic innovations in the manner of studies, inventions, and fantasies. The next set, Op. 11, dates (all but one piece) from 1917-1918 and concentrates on an expanded interpretation of folk material while still using rich and dissonant harmonic resources as well as the new freedom of articulation and color staked out in the earlier work. Finally, the Marosszek Dances of 1927- better known as an orchestral work but apparently originally composed for piano- take us into the simpler, popularizing atmosphere of the late 1920's; the harmonic treatment here is much more traditionally modal-tonal, with catchy dance rhythms predominating everywhere. This music is very appealing, but it is the Op. 3 and the Op. 11 sets that make the deeper impression; they ought certainly to be rated with the Bart6k Bagatelles and other early twentieth century keyboard music.

Gyorgy Sandor, like many outstanding Hungarian musicians of his generation a disciple of Kodaly, is an ideal interpreter of this music. The piano sound is strong, not overly beautiful, but clear. One feature that disturbs me, however, is the apparent use of studio controls to create or reinforce dynamic levels; also, there is a fair amount of surface noise that offsets some of the value of the Dolby recording. - E.S.

LESUR: Symphonie de Danses; Serenade for String Orchestra; Pastorale. Chamber Orchestra of the ORTF, Edouard Lindenberg cond. MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1662 $3.50 (plus 750 shipping, from the Musical Heritage Society, Inc., 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performance: Very good

Recording: Good

In the United States one comes across Daniel Lesur's name in connection with those of Messiaen and Jolivet, together with whom Lesur (his given and family names are often hyphenated--I never have understood why) and Yves Baudrier founded the group called Jeune France in 1936. But Lesur's music is an unknown quantity here and has not, to my recollection, been available on records before.

This is an intriguing discovery: ingratiating music (Lesur's credo places enjoyment fore most among his musical objectives) in an idiom that presents no problems and yet has a highly individual character.

The Symphonie de Danses, the longest and most recent (1958) of these three works, is scored for strings, piano, timpani, and tambourine and is in ten brief movements, many of whose boldly drawn themes have the flavor of folk music. The three-movement Serenade actually quotes folk material-an infectious dance tune from the Pyrenees in the finale and a Spanish theme that appears in both outer movements. The work is said to be related to the character of Don Juan- possibly, one surmises, because Don Giovanni was being given at the Aix-en-Provence Festival of 1954, at which the Serenade was premiered.

(There is no allusion to Mozart in the music, which, however, has much in common with similar works of the great figure from Aix, the late Darius Milhaud.) the Pastorale, com posed in 1937 when Lesur was twenty-nine, is in the nature of a four-movement concerto grosso in which a woodwind quintet, trumpet, and piano constitute the concertino, with a ripieno of strings and timpani: in it are flashes of the chinoiserie and other exoticisms heard also in the Symphonic.

I enjoyed these imaginative and unpretentious pieces enormously, and I even suspect the finale of the Serenade could "do a Pachel bel" and make the charts one of these days.

Fine performances, good sound. R.F.

LISZT: Piano Sonata in B Minor (see CHOPIN)

MONTEVERDI (arr. Rodriguez): L'Inco ronazione di Poppea (Concert Suite). ROD RIGUEZ: Canto; Lyric Variations. Sue Harmon (soprano); Michael Sells (tenor); Michael Sanders (piano); Orion Chamber Orchestra, Edward Nord cond. ORION ORS 74138 $6.98.

Performance: Good

Recording: Good

Since the surviving manuscript of Montever di's L'Incoronazione di Poppea gives no clue (except for hints about harmony) to the com poser's original scoring, this great master piece must be arranged for a modern performance. The problems are many, and I do not recall a single effort which met with unanimous critical approval. Two recent stagings based on editions by Alan Curtis and Raymond Leppard came in for their share of criticism, though Leppard's version (staged in Glyndebourne, London, and at the New York City Opera) did score high marks for dramatic viability.

It is a safe assumption, therefore, that Robert Xavier Rodriguez's "Concert Suite" will be devastated by academically oriented critics. Its twenty-eight-minute condensation is a totally inadequate representation of the opera, and the scoring follows Leppard's example in "Romanticizing" the music away from the seventeenth century's ostensible austerity.

Nonetheless, the editor's declared aim "to introduce this early Baroque masterpiece into the modern orchestral repertoire" seems eminently reasonable. Viewed in this way, the elimination of most of the action (the work is reduced to a sequence of two duets and one aria by Nero and Poppea) and the creation of additional brief sinfonias out of vocal pas sages make some kind of musico-Machia vellian sense-at least to me. In any case, al though the orchestra plays very well, the singers are only adequate. Nero sounds aggressive and hard-toned most of the time, and his lapsing from the martial manner into tender falsetto crooning is unconvincing. Above all, the sensuousness of the music is not communicated.

Rodriguez's own Canto is ingeniously conceived. The scene is the episode of Paolo and Francesca as related by Dante-the reading of the Lancelot-Guinevere legend by the lovers, with the tenor actually quoting from a thirteenth-century French source. The music is well constructed along serial lines, but it proves inadequate to the task of conveying the torrid atmosphere; it builds toward various climaxes without ever suggesting the right one. The brief Lyric Variations for oboe, two horns, and string orchestra, on the other hand, offer a very effective blend of serial techniques and lyrical expressiveness.

Rodriguez and conductor Nord are both young Californians, members of the University of Southern California faculty. Both are gifted musicians, and we will surely hear more of them. The Orion Chamber Orchestra is a first-class group, and the horn playing in the Lyric Variations is outstanding. GJ.

MOURAVIEFF: Nativite for String Trio and Orchestra (see SHOSTAKOVICH) MOZART: Arias for Soprano and Orchestra.

Popolo di Tessaglia . lo non chiedo, eterni dei (K. 316); Schon lacht der holde Fruhling (K. 580): No. no. the non sei capace (K. 4/9); Min speranza adorata . . . Alt non sai, qua! pena (K. 416); Bella mia fiamma, addio . . . Resta, o care (K. 528). Jana Jonagova (soprano): Prague Chamber Soloists, Zdenek Lukag cond. SUPRAPHON 112 1114 $6.98.

Performance Virtuosic

Recording Very good

There may not be much profundity in Mozart's bravura arias for soprano and orchestra-he wrote many of them for his gifted sisters-in-law Aloysia and Josefa Weber-but there is abundant melodic invention, frequently enhanced by writing of remarkable imagination. Collections devoted to these arias do not seem to stay in the catalog very long, however: relatively recent and very fine recordings by Maria Stader, Rita Streich, and Gundula Janowitz have already been deleted.

These are the artists against whom Jana Jonagova, a member of the Prague National Theatre, has to be measured-and she comes off very well indeed.

The Czech soprano's voice appears to be smallish in size, the timbre a bit piercing and lacking in warmth. Its agility is spectacular, however, and its command of the uppermost range recalls the remarkable Mado Robin (she ascends to a G above high C in the K. 316 aria). Moreover, Miss Jondiova handles the fioriture fluently and accurately, with the ease essential to these virtuoso pieces. Her enunciation of the texts is a bit careless, a quality that could be more damaging in a dramatically more meaningful repertoire.

The origin of this collection lends special significance to the K. 528 scena, which was written in Prague in 1787 while Mozart was working on his Don Giovanni. The scena is an astonishingly chromatic work, virtually "experimental" writing for its time.

We may be hearing more of Jana Jonagova in time to come. On the present disc she gets competent but very literal accompaniments--appoggiaturas are generally ignored-but the recorded sound is full and lively.

MOZART: Cosi Fan Tutte (see Best of the Month, page 85)

PERSICHETTI: Sonata for Two Pianos, Op. 13 (see Collections-Modern Music for Two Pianos)

POULENC: Aubade for Piano and Eighteen Instruments (see D'INDY)

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

PROKOFIEV: Violin Concerto No. 1, in D Major, Op. 19; Violin Concerto No. 2, in G Minor, Op. 63. Stoika Milanova (violin); Symphony Orchestra of the Bulgarian Television and Radio, Vassil Stefanov cond. MONITOR HS 90101 $3.49.

Performance: Superb!

Recording: Excellent

As one who grew up on the classic recorded performances of these works--No. 1 by Szigeti-Beecham and No. 2 by Heifetz-Koussevitzky--let me say that twenty-nine-year-old Stoika Milanova can stand right up to both the old masters, as well as to most violinists that have come since, including her own mentor, David Oistrakh.

The D Major Concerto is the real dazzler, displaying solo virtuosity and musicianship, fine orchestral collaboration under conductor Vassil Stefanov, and well-nigh perfect recorded sound in terms of balance, frequency range, dynamics, and acoustic ambiance.

Miss Milanova has far more to offer here than unerring intonational marksmanship and acrobatic dexterity; she clearly feels the music's flow and architecture, the way each part, in phrasing, articulation, dynamics, and rhythm, relates to every other part. To quote Leonard Bernstein (in a wholly different context), here is a performance in which "everything checks out." The G Minor Concerto fares every bit as well in execution and interpretation. To the wonderful slow movement Miss Milanova brings just the right amount of expressive intensity without ever falling into the trap of sentimentality-a very easy thing to do in this particular music. Again, Mr. Stefanov and his players provide first-rate backing, but the re cording is just a shade less than perfect; the more reverberant acoustic here makes the horns too prominent, especially in the first movement, Nevertheless, I can certainly understand why the French Charles Cros Academy jury voted this disc one of its 1972 awards. At $3.49 the record is a fantastic buy, and a most auspicious beginning for Monitor's projected series of issues from the Bulgarian Balkanton label. D.H.

PROKOFIEV: Visions Fugitives, Op. 22; Son atina in E Minor, Op. 54, No. 1 ; Sonatina in G Major, Op. 54, No. 2. David Rubinstein (piano).

MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1794 $3.50 (plus 75¢ handling charge from the Musical Heritage Society, Inc., 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performance: Very good

Recording: Excellent

David Rubinstein is known to me only through his earlier MHS disc, an agreeable collection of Sibelius piano music. He shows a good feeling for these more familiar works of Prokofiev, projecting the varied moods of the twenty Visions Fugitives with insight as well as skill and balancing the alternately ironic and lyrical moments in the two sonatinas most convincingly. Gyorgy Sandor offers more subtlety in his accounts of these works, and both Richter and the other Rubinstein have probed a little deeper in their respective bundles of excerpts from Op. 22, but this new MHS release is a convenient, eminently recommendable package, with richly realistic piano sound in the bargain. R.F.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

RACHMANINOFF: Five Pieces, Op. 3; Preludes, Op. 23. Ruth Laredo (piano). COLUM BIA M 32938 $6.98.

Performance: Coruscating

Recording: Crisp and clean

Ruth Laredo's remarkable Scriabin piano sonata series on the Connoisseur Society label--not to mention her superb concert work in and around New York City-has led to her recognition as one of the most brilliant key board artists of the younger generation. So it was almost inevitable that eventually she would be pursued and signed by one of the major record companies.

Columbia has elected to have Miss Laredo make her debut for the label with a Rachmaninoff package. Fortunately, the choice of repertoire takes the form of an intelligently selected pair of sequences rather than a miscellany. The Op. 3 Pieces include the celebrated C-sharp Minor Prelude as well as the brilliant and popular Polichinelle, and the greater part of the disc is taken up with an integral recording of the ten Op. 23 Preludes, the only stereo version currently available on American la bels other than that included in the Michael Ponti Vox Box of Rachmaninoff piano music.

Like Rachmaninoff's own performances of his solo piano works, Miss Laredo's is essentially aristocratic in tone, ample in sentiment, but with no concession whatever to the temptation these pieces offer to indulge in mere sentimentality. Also like Rachmaninoff's in his prime, her finger work is immaculate and her rhythmic sense both precise and propulsive. Her playing of the Polichinelle and of the rich-textured B-flat Prelude, Op. 23, No. 2, are stand-out examples of this latter quality.

Her remarkable command of textural clarity is most notable in the C Minor and A-flat Major Preludes, as well as in the etude-like E-flat Minor, with its extreme demands for crystalline performance of the passage work.

The purely lyrical pieces, such as the Engle that begins Op. 3, and the opening and closing of Op. 23, together with Nos. 4 and 6 of that set, come off beautifully indeed, but I'm not sure that Columbia's recording does Miss Laredo's playing full justice here. Upon listening again to her Desto disc of Scriabin Preludes, I found that the somewhat more distant microphone placement, along with the warmer acoustic ambiance, yields more tonal richness and subtle dynamic differentiation than is the case with the Columbia. On the other hand, the crispness and clarity of the Columbia sound does wonders for the more complexly textured pieces. On the whole, this is an excellent recording-the best we have of Op. 23.

But I hope that Columbia's future issues of Miss Laredo will communicate somewhat more effectively the essential warmth of her playing as it has been demonstrated by Connoisseur Society and Desto. D.H.

REINECKE: Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 72 (see D'ALBERT) REUSNER: Suite in F Major (see WEISS) RIEGGER: Variations for Two Pianos, Op. 54a (see Collections-Modern Music for Two Pianos) RODRIGUEZ: Canto; Lyric Variations (see MONTEVERDI)

RUBINSTEIN: Piano Concerto No. 3, in G Major, Op. 45. KABALEVSKY: Piano Concerto No. 3, in D Major, Op. 50 ("Youth").

Robert Preston (piano): Westphalian Symphony Orchestra, Paul Freeman cond. ORION ORS 74149 $6.98.

Performance: Lively

Recording: Okay

Here are two monster Russian keyboard extravaganzas, one by the legendary Anton Rubinstein, the other by the ever-popular Kabalevsky, the one grand and pompous, the other light and skittish. Neither is a very important work, but Robert Preston does his best to lend them substance and fire. I am not a Kabalevsky admirer, but I must say that Preston and the modestly skilled German orchestra under the capable direction of Paul Freeman really make this lively concerto bounce right along. The recording is fairly good, although now and then the orchestral balances are off by a good bit. E.S.

SCHUBERT: Sonata in B-flat Major, Op. posth. (D. 960); Impromptu in A-flat Major, Op. 142, No. 2 (D. 935). Clifford Curzon (piano). LONDON CS 6801 $6.98.

Performance: Watery

Recording: Okay

This is a curious performance that permits Schubert to go soggy at the seams. The long, exquisite B-flat Sonata must be held together by the tension of long lines, impeccable timing, a sense of direction, articulation, larger form. I find little of that here. Above all, Curzon lacks timing-his playing is full of inexplicable and ineffective little tempo changes and without a firm shape the poetry goes limp.

Schubert's divine length seems endless and directionless. No stars. E.S.

SCHUMANN: Humoreske, Op. 20; Waldszenen, Op. 82. Wilhelm Kempff (piano).

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 410 $7.98.

Performance: Conscientious

Recording: Good, though a bit hard

As much as I have always respected Wilhelm Kempff, he never has been my man for Schumann. This new recording does little to change my opinion. When I compared it with his 1968 Davidsbilndlertdnze and Papillons, I found almost no difference in performance approach between the two: everything is very correct--and just a trifle stodgy. This is fatal in a work like the Humoreske, whose way ward poetry is far better captured by young Jerome Rose in his Turnabout recording.

Kempff fares somewhat better in the less demanding Waldszenen. But again, I prefer a younger man's reading: Christoph Eschenbach's performance (also on Deutsche Grammophon) is more poetic, with not one whit less musicality or fine pianism.

I don't think Kempff 's somewhat pedagogical treatment of Schumann is wholly the source of my discontent. His rather hard-toned instrument, the qualities of which are evident in both this and the 1968 recording, is also partly responsible. The recording, as such, therefore, is all too clear for me. D.H.

SCHUMANN: Missa Sacra in C Minor, Op. 147. Gertraut Stoklassa (soprano): Manfred Raucamp (tenor); Bernard Schmieg (bass): Philharmonia Vocal Ensemble and Orchestra, Stuttgart. Roland Bader cond.

MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1796 $3.50 (plus 75c handling charge from the Musical Heritage Society, Inc.. 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performance: So-so

Recording: Fair

Schumann wrote a great deal of large-scale sacred music in his last years, much of it little known and almost never performed. This Mass, a really substantial composition for soloists, chorus, and orchestra, was one of his last compositions before madness and silence overtook him, and, like most of his late works, it has been relegated to the dust bin. In fact, it is likely that this Mass was never performed at all until recently, even though, along with all the other unperformed, obscure, late works, its score sits in the music libraries in the big complete editions.

This is not the sort of piece that recom mends itself immediately. It is an ungainly, sprawling work with a long, long Gloria fol lowed by a long, long getting-through-the-text Credo. The opening Kyrie is a rather touching and original conception, but it is only in the second half of the work that Schumann hits his stride. He interpolates an Offertorium for soprano solo with cello obbligato. This is fol lowed by a large, rather inspired movement that combines the Sanctus and Benedictus with another interpolated sacred text: the final Agnus is effective too.

The soloists are notably pure-voiced (I'll bet they specialize in an earlier century or two), but the chorus is large and clumpy, and the orchestra does not always seem to be in tune. Tempos drag, and, well, it will take something more than this performance to put Schumann's Mass into the repertoire of choral societies and the hearts of music lovers.

E.S.

SENFL:Missa Per Signum Crucis (see ISAAC)

SHOSTAKOVICH: Chamber Symphony for String Orchestra, Op. 110.

TCHEREPNIN: Ten Bagatelles for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 5.

MOURAVIEFF: Nativite for String Trio and Orchestra. Jurgen Meyer-Josten (piano, in Tcherepnin): Wurttemberg Chamber Orchestra, Heilbronn, Jorg Faerber cond.

TURNABOUT TV-S 34545 $3.50.

Performance: Splendid

Recording: Likewise

Since Shostakovich wrote his Symphony No. 14 for chamber orchestra (with vocal soloists), one might wonder why the "Chamber Sym phony" in this album was not assigned a sym phony number. The explanation, given only in the German version of the bilingual annota tion, is that Op. 110 is actually the String Quartet No. 8, arranged for string orchestra by Rudolf Barshai (who has made a similar setting of Prokofiev's Visions Fugitives, and for whose Moscow Chamber Orchestra Shos takovich wrote his Fourteenth Symphony). In constructing the quartet itself, Shostakovich used materials from his Symphonies Nos. 1, 7, 8, and 11, the Cello Concerto No. 1, the Pi ano Trio No. 2, the opera Katerina Ismailova, and a song called Languishing in Prison: it is a somber and intense work titled "In Memory of the Victims of Fascism and War." Although I would not wish to do without the original version (in the Borodin Quartet's magnificent Seraphim sets of Shostakovich's first eleven quartets, cited by Irving Kolodin in "The Private Shostakovich" last May), the expanded setting is also a very effective one, and the Wurttemberg ensemble, usually heard in much earlier music, has never sounded better.

Tcherepnin's Op. 5 as presented here is that composer's own expansion of music he wrote for solo piano before he was twenty.

Some forty years later (1959) he did a version of the Bagatelles for piano and full orchestra (the version recorded by Margrit Weber and Ferenc Fricsay on Deutsche Grammophon 138 710), and the following year produced the setting for piano and strings recorded here.

The stylish, urbane, thoroughly engaging na ture of this music readily explains his long fascination with it.

Leon Mouravieff, evidently a Frenchman now, was born in Kiev in 1905. His Nativite is identified as the first part of a triptych called La Mere, in which the two succeeding pieces are Pieta and Notre Dame. One can hardly keep from observing that a work titled La Mere would seem to be foredoomed by the earlier presence of a masterpiece called La Mer, but the confusion will probably not arise, for this piece (not a descriptive Christmas scene, but more in the nature of a "meditation") is only moderately interesting. Like the two more substantial works on the disc, how ever, it is splendidly played and recorded, with rich, full-bodied string tone that is a pleasure in itself. R.F.

SIBELIUS: Symphony No. 4, in A Minor, Op. 63; The Swan of Tuonela, Op. 22, No. 3. New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein cond. COLUMBIA M 32843 $6.98.

Performance: Romantic

Recording: Full-bodied

The first time I heard Leonard Bernstein's reading of the always knotty and interpretive ly elusive Sibelius Fourth Symphony was in its initial release as part of Columbia's 1969 set of all Sibelius' symphonies. It is useful to hear it again here without having to deal with the other six symphonies at the same time.

(Incidentally, I assumed initially that this version of The Swan of Tuonela was also a reissue, but it turns out to be a new release.) The Fourth Symphony's slow movement.

Sibelius' greatest, is the crown of this unique work, and it is the most successful part of Bernstein's interpretation. The other three movements remain problematic in one way or another. Bernstein's very slow tempo allows him to extract many beauties of coloristic de tail from the first movement, but it does not help the music in terms of cohesiveness. The enigmatic scherzo always presents the problem of how much to slow down, if at all, for the prominent triadic-intervals episode for flutes that marks the dramatic watershed of the movement; Bernstein slows down quite markedly. In the finale there remains the question as to whether the "Glocken." speci fied in the score are really Glocken (bells) or glockenspiel. All Finnish conductors and most others opt for glockenspiel; the Stokowski and Rodzinski 78-rpm recordings use bells, as does the Ansermet stereo LP. Bernstein uses bells and glockenspiel together.

Curious. My real beef with Bernstein, however, is his unfortunate sentimentalization of the grim closing pages.

As for the magical Swan of Tuonela (the English horn soloist here is Thomas Stacy), Bernstein makes her voyage down the River of Death much longer than most other inter preters of the work on records. Again, how ever, his realization of coloristic details (the soft bass drum rolls, the col legno strings) is altogether superb, and Columbia's recording does both this and the Fourth Symphony full justice.

Of currently available recordings of the Fourth Symphony, Lorin Maazel's is the most excitingly dramatic and forthright, and Kara jan's is the most refined and poetic. The most rugged reading of all (and the hardest to come by) is a mono USSR MK disc by the late Tauno Hannikainen-a very powerful read ing, this. My current preference is Maazel's London disc, which offers a fine Tapiola per formance as filler.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

STRAUSS: Concerto for Oboe and Small Orchestra; Concerto No. 2, in Elicit Major, for Horn and Orchestra. Lothar Koch (oboe): Norbert Hauptmann (horn): Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan cond. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 439 $7.98.

Performance: Excellent

Recording: Superb

Both of these performances are special by any standards. The Berlin Philharmonic's first-chairmen play with great fluency and style, Karajan of course brings out every subtle shading in these autumnal scores, and the sound is at or near Deutsche Grammophon's formidable best. The opening tempo for the Oboe Concerto, just the slightest bit more relaxed than in most other performances. is especially convincing-but both sides reflect the abundant affection that must have gone into this beautiful production.

Despite the very deep satisfaction obtain able here, I still prefer Heinz Holliger's version of the Oboe Concerto on Philips 6500 174 because of his more attractive tone, and I still find incomparable Dennis Brain's Strauss horn concertos on Angel mono 35496. Those who feel less strongly about this, however, or who simply insist on stereo for Strauss, will find nothing but pleasure in this excellent DG release. R.P.

TCHEREPNIN: Ten Bagatelles for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 5 (see SHOSTAKOVICH)

TIPPETT: The Vision of St. Augustine; Fantasia on a Theme of Handel. John Shirley-Quirk (baritone): Margaret Mitchen (piano, in Fantasia): London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Sir Michael Tippett cond. RCA ( Great Britain) SER 5620 $6.98.

Performance: Authentic

Recording: Mostly very good

Many who have responded eagerly to the dramatic utterance of Michael Tippett's Third Symphony (1973), the oratorio A Child of Our Time (1944), or for that matter to the more complex and subtle operas, The Knot Garden (1970) and Midsummer Marriage (1952), or the elegantly textured Concerto for Double String Orchestra (1939) may find themselves in for somewhat rougher going with The Vision of St. Augustine, commissioned by the BBC and premiered on January 19, 1966, with Fischer-Dieskau singing the enormously taxing solo role taken over so ably by John Shirley-Quirk in this recording.

Tippett is by background and predilection a "learned" composer in the best meaning of that word-which is to say that, in company with the Netherlands masters of the Renaissance, he is in touch with every aspect of his cultural milieu, past and present, and is fear less when it comes to integrating aspects of it into his music. The whole armory of his musical and cultural know-how is brought into play in The Vision of St. Augustine--a thirty-five-minute, Latin-text work built around Chapter X:23-35 of The Confessions of St. Augustine. Here Augustine describes a remarkable conversation with his mother five days before her death, in the course of which they experienced a fleeting vision of Eternity.

It is this narrative which is carried by the baritone soloist throughout the score. Meanwhile, the chorus and orchestra, operating, so to speak, on other levels of discourse, provide an immensely complex commentary-some of the text being from the Bible, some from Augustine's own meditations on the nature of time.

In order to convey the complexity and anguish of Augustine's own ponderings, perplexities, and compulsion to comprehend and come to terms with his experience, Tippett has developed a comparably complex vocal and instrumental tapestry, which is distantly related to certain works of Ives and Penderecki, although there is none of the sheer shock effect of the latter and little of the pictorialism of the former.

Tippett's handling of his forces is immensely knowledgeable and brilliant, most obviously in the orchestral interlude bridging the first two of the music's three sections. Frankly, I find verbal description and analysis of The Vision of St. Augustine virtually impossible, and perhaps not necessarily desirable. But I do recommend careful study of the text in English prior to listening to the work.

The inclusion of the relatively early Tippett Fantasia on a Theme of Handel for piano and orchestra as a filler seems both anticlimactic and incongruous here. The theme derives from the same source as Brahms' famous set for solo piano, except that Tippett uses the chord progression rather than the theme it self as Brahms did. I'm not sure that Tippett's piece really works: it sounds rather labored and a bit scrawny texturally in parts, despite brilliant moments at the opening and close.

Perhaps the recording is to blame, for the piano sounds very close-up and the strings rather lacking in genuine body and presence On the other hand, the recording of The Vi sion of St. Augustine cannot be faulted in any way. Balances between soloist, choir, and orchestra are remarkably well maintained, with great fullness and brilliance of sound.

The performance itself can only be described as a minor miracle, particularly on the part of John Shirley-Quirk, who can look upon this performance as one of his very finest. (A note on availability: although this recording is on the British RCA label, it is being imported by RCA and distributed through regular RCA channels in this country.) D.H .

VIVALDI: Il Cimento dell'Armonia e dell'Invenzione, Op. 8. Piero Toso (violin): Pierre Pierlot (oboe); I Solisti Veneti, Claudio Scimone cond. MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 1727/9 three discs $10.50 (plus 75 cents handling charge from the Musical Heritage Society, 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Performance. Virtuosic but idiosyncratic

Recording: Good but over-resonant

Depending on your individual view, you will find this integral recording of the twelve concertos of Vivaldi's fancifully entitled Op. 8 ("The Trial, or Test, of Harmony and Invention") either an exhilarating experience or an at times maddeningly wayward performance. Certainly one cannot fault the brilliance of the playing, either solo or ensemble.

The precision is exceptional, and the playing overall has just the right Italianate fire and, where required (as in the programmatic concertos, The Four Seasons, The Storm at Sea, The Pleasure, and The Hunt), all the proper graphic effects.