by IRVING KOLODIN

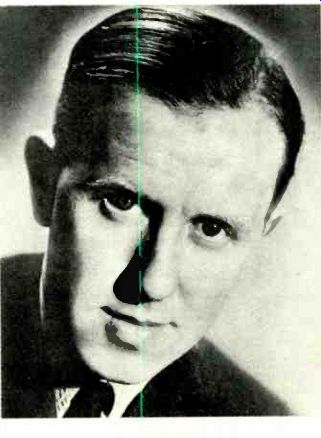

AKSEL SCHIOTZ (1906-1975)

IF ever an artist was bedeviled in his life-time, that artist was the late Aksel SCHIOTZ. The development of an artist is a slow, pains taking business and virtually unrewarding in itself. But the long way is lit, at least, by the expectation of some final fulfillment, just compensation for the work, the effort, and the sacrifice that have gone into the building process. For Schiotz, fulfillment was almost un conscionably delayed--from 1939, when he was ready for recognition as the lieder singer of his time, until after 1945, when he and all the Danes were finally freed from the German occupation.

SCHIOTZ's moment came at last in the summer of 1946, with appearances at Glyndebourne and at the Edinburgh Festival. It was perhaps the sweeter for being delayed, but it was also maddeningly brief. The bright hopes of that summer turned almost to a death watch by December, when Schiotz under went one of the most delicate operations a surgeon can undertake. A sudden onset of double vision had given warning that Schiotz was afflicted with a tumor of the acoustic nerve. The surgical procedure has become known medically (after another famous musician who did not survive it) as "the Gershwin operation." Schiotz did survive, but at the cost of a predicted penalty: lifelong paralysis of the right side of the face.

Blighted careers are subject to many forms of frustration. It was Schiotz 's particular curse to have in existence tangible, demonstrable, recorded evidence of the beautiful sound, the rare musical art, the exquisite command of language that made him a master interpreter of vocal music--and to know that, after his surgery, he would never be able to produce them again.

As time progressed, he accepted the inevitable-first by performing in the baritone range and then by applying his intelligence and insight to teaching (a profession for which he had originally been trained). But when he and I first became acquainted, the operation and its aftermath were still fresh memories, the hope that a miracle-plus exercise and patience-might restore his faculties to a functional level at least was still alive.

This was in the fall of 1948, when his New York debut was one of the eagerly awaited events of the new musical season. It was known that Schiotz had been ailing and inactive, but neither the cause nor the duration of his problem were yet clearly understood publicly. A representative of his manager (who, I learned much later, had read my comment of the previous year which had likened Schiotz's singing of Handel to John McCormack's and had booked him, unheard, because "John" had long been one of his favorite clients) suggested a meeting. To my surprise and shock I was confronted by a cordial, well-spoken man in his early forties with a cruelly contorted right lip and lower jaw. As the total effect of this deformity on his singing could not be judged until his first public performance, I wrote nothing about the visit until after his Town Hall concert. It was textually well-handled and musically scrupulous--but I had to add that it was also "effortful and uncertain" vocally, that Schiotz was "taxed to reach a G." As our acquaintance broadened, I discovered the reasons why Schiotz had come to America when he did. (My first question drew the response that, yes, he had been warned that it was too soon after surgery, but he had begun to sing in Copenhagen nonetheless only weeks before.) The first reason he gave was the gnawing human necessity to know whether he could face an audience again; the second, he confided, was simply financial need.

Following the expensive surgery, he had been advised to seek tranquility in a long (and costly) sea voyage. It took him from Denmark to South America, across the Pacific. and back again to Europe through the Suez Canal. The two things taken together, and the need to provide for a wife and four (eventually five) children, made inescapable a return to the one thing he knew: public performance.

Some months later, I received a Christmas greeting from Schiotz which contained the following note: "Health is improving and voice too. Apparently it was mad to come to New York last year, but I learned more there in three months than I would have learned at home in three years. So it was not lost." In the years that followed, I would meet Schiotz of ten in the oddly unexpected places where a performer's path and that of an itinerant critic might cross: at Perpignan during a Casals Festival; in Boulder, Colorado, where Schiotz was teaching at the University of Colorado; and most recently in St. Paul, Minnesota, a few years ago, where he had been invited to attend the American premiere of Carl Nielsen's opera Muskarade.

In other circumstances--perhaps if he had been prevented from singing altogether Schiotz might have reaped something sizable from his treasury of recordings. Before his voice was impaired, he had recorded a total of more than two hundred sides (as documented in a fine discography published in 1966 by the National Diskoteket of Copenhagen), of which many were Danish materials not readily marketable elsewhere. Outside Scandinavia, where many of the communal musical properties (Grieg, Nielsen, Svendsen) did circulate, record companies were--as they notoriously are--loath to perpetuate discs by living, but no longer prominent, performers.

Angel has been a conspicuously creditable exception to this rule; its three discs of "The Art of Axel Schiotz" contain, in their Seraphim reissues, fourteen Nielsen songs (Vol. I, 60112), Schubert's Die Schune Mullerin (Vol. II, 60140) with Gerald Moore as the incomparable collaborator, and another of selections with orchestra (Vol. III, 60227) ranging from the superb "Comfort ye, my people" and "Every valley" from Handel's Messiah to six great Mozart arias. These three records would in themselves be sufficient to make any tenor's reputation. But they were not enough for Schiotz, for he was not "any tenor." Perhaps the happiest thing that happened to Schiotz in his years of unhappiness was the appearance in the United States in the early Fifties of his famous recording, with Gerald Moore, of Schumann's Dichterliebe (RCA LCT 1132) backed with the historic performance of the same work by Charles Panzera (with pianist Alfred Cortot), a baritone of an earlier generation. It was an instance of corporate noblesse oblige that might well be emulated in these latter days of duplicated riches. The suggestion for the coupling came to me from a correspondent who asked me to relay it to RCA. I had reason to believe that Panzera would be the last artist in the world to object to having his performance bracketed with one by Schiotz. During his only visit to America (in the summer of 1948. when he conducted a master class at the Juilliard School), I became acquainted with both Panzera and his wife, and I introduced them to the Schiotz recording of Dichterliebe. After sampling a few songs, he turned to his wife, fellow professional and pianist Madeleine Panzera-Baillot, and exclaimed: "But this is unbelievable! I have never heard such vocal art!" Another twenty-five years of listening and a recent rehearing of the Schiotz-Moore Dichterliebe have, I think, given me an insight I did not then have into Panzera's meaning.

There is, as anyone can hear, a remarkable legato line throughout Schiotz's reading of the cycle, an uncanny interrelation of word and tone, a smooth, gearless shift from piano to forte and back again. But, if you listen in a particular state of awareness, you may suddenly become conscious as well, as I lately did, of something you do not hear: any intake of air, any sense of a note's being truncated because it lies in an awkward place, or consonants unpronounced because their omission might make the singer's task easier. To state it affirmatively, one is aware of a breath sup port so complete, so uninterrupted, that the vocal statement sounds as effortless as it must have been effortful to master.

Perhaps the best demonstration of what Panzera characterized as "unbelievable" comes in the five-part series of "Danske Sange" which accounts for nearly one hundred of Schiotz's numerous song recordings (EMI/Odeon E 051-37021/5. $5.99 each at import outlets).

Jacket information about the contents is restricted to the names of the songs, their composers, and their poets (when known): no text. let alone translation, is offered. Lacking even a word of Danish, I was nevertheless enthralled as song succeeded song and side succeeded side. Merely by inflection alone, Schiotz kept me with him all the way, never in the least doubt just what emotion was at issue. Whatever the shade of sadness (grave. pensive, wistful) or of glad ness (quiet, triumphant, exultant), it was all there in the Schiotz sound. It was a sound pure, fervent, square on pitch, intensely individual-and, sadly, never the same after the surgeon had done his life-preserving work.

Taken together, these five discs memorialize Schiotz as something more than a great vocalist, a prime artist, or a performing personality. He was a man born to do one thing, and to do it supremely well-to sing. This applies no less to Oscar Rasbach's Trees and Cole Porter's Night and Day (both of which he recorded in the summer of 1941 in flawless English) than to Grieg's setting of Hans Christian Andersen's Jeg Elsker Dig (one of the least effusive and most eloquent versions of that great love song ever), or to the simple strains of Mor Danmark, performed almost daily by Schiotz during the occupation.

WHEN one has heard, say, a hundred and fifty performances of Schiotz on record in a week's time (there is a further collection of seven LP's on Danish Odeon--MOAK 1, 2. 3, 4, 5, 19, and 20--which duplicates much of the content already mentioned but searches out some other matter as well), one is impelled to recognize one basic fact: Schiotz was a rare order of artist, one who fulfilled completely the precept that the style should be the man. He was thoroughly consistent in singing the way he lived and in living the way he sang, a man who faced up to the challenge of his tragically shortened career as courageously as he did to the invaders--not conquerors--of his beloved country.

One of the greatest of all his performances was of Haydn's "Mit Wurd und Hoheit Angetan," from The Creation. In it, he made such words as "ein Mann und Konig der Natur" ("a man and king of nature") live for us because they were words by which he himself lived. Aksel Schiotz died of cancer on April 19, 1975.

==============

Also see:

THE BASIC REPERTOIRE, MARTIN BOOKSPAN