.

Country music is the only organism in the American culture that could put on such a show.

By Noel Coppage

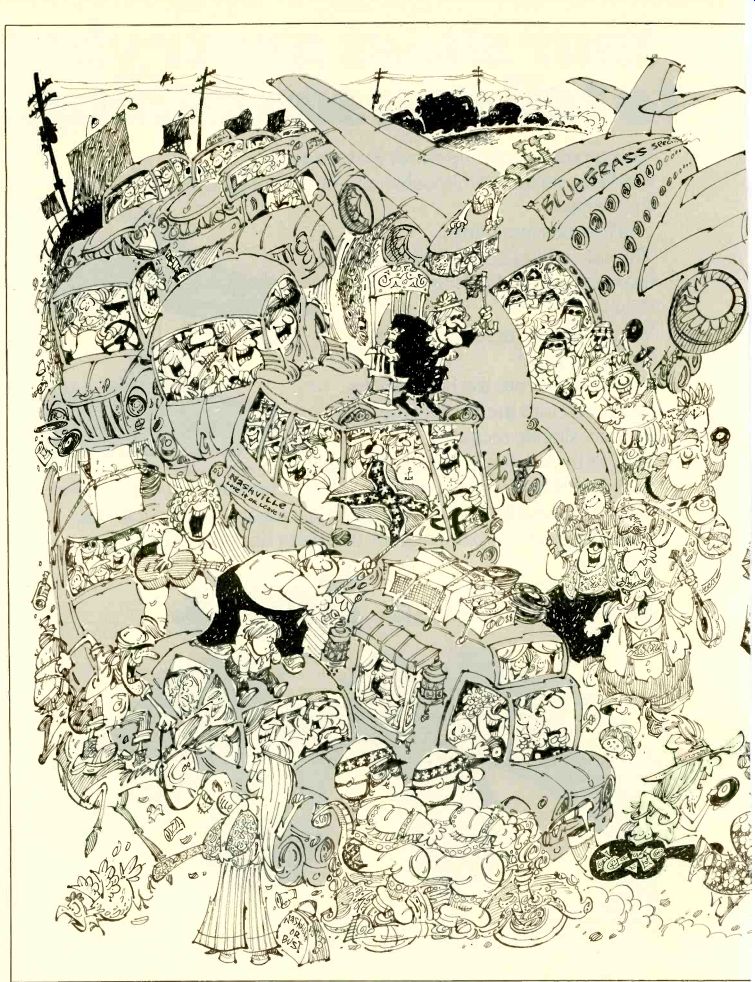

Four of them drove down from Sleepy Eye, Minnesota. The announcer, reading notes passed up from the audience, read that, and about "a whole airplane load of folks all the way from Norway." Others had come from Germany, Switzerland, Eng land, New York, Philadelphia, and, among other places, Fitchburg, Massachusetts, where a country-music disc jockey sometimes brings his small son to the studio and the people out in radio land get to hear him tell the lad to be quiet. By bus and by car they came from every state known to man, including Ohio, which sends more citizens to the Grand Ole Opry every Saturday than any other state (averaging 91 more than Indiana and 169 more than Tennessee), and one sturdy little clump of folks rode down from Buffalo, through all kinds of rain and lightning, on motorcycles.

There were enough Okies from Musko gee to start a football league and, according to another note, three half-breeds from Holland, Michigan.

It seemed important on and off the stage, this matter of communicating how far they had come and how much or how little trouble it had been to find shelter for themselves and their machines. They had accomplished a pilgrimage, with the help of air-conditioned Chevys and Ramada Inns, the main thing about a pilgrimage being the common reverential attitude that attends it, and they were entitled to savor it. That it was a sure enough pilgrimage all right was verified by the way the people who run country music and the people who make it (artists, they are invariably called) bent back and strained blood vessel for five days to woo them, these fans, these folks, in ways you don't often see 12,000 people wooed. (Continued overleaf)

The International Country Music Fan Fair is what they call the event, and Nashville naturally is where they hold it, every year as soon as the planting is done; country music is the only organ ism in the American culture that could or would put on such a show. It is sponsored jointly by the Country Music Association, whose members are debating whether giving awards to such pop stars as John Denver and Linda Ronstadt is the way to keep country music "country," and by the Grand Ole Opry, an institution threatening to become as big as the telephone company. The fair, the fourth-year version that I saw, was something like an old-time camp meeting (with dinner moved up from the ground to the Municipal Auditorium plaza deck, but with a tent top shading it all the same), something like a music festival, something like a pep rally, something like a family reunion, something like an overgrown Tupperware party, and quite a lot--embarrassingly enough for some of us-like Norman Rockwell's vision of small-town America as drawn up twenty years ago and updated in the most casual and offhand manner. It was, in short, a gentle rebuff to anyone taken with the coastal notion that radical changes in recent years have shaken up the whole country. And it was also like what you always get at the end of a pilgrimage-a veritable orgy of church attendance.

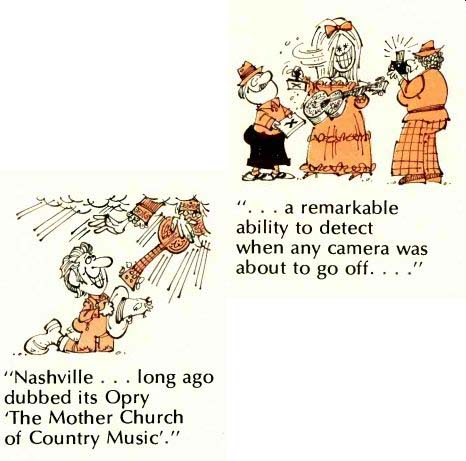

Nashville, way ahead of any of the rest of us, long ago dubbed its Opry and, by implication, its whole self "The Mother Church of Country Music." Country fans from all over go down or up to Nashville and gorge themselves until they have to sit down, feasting, feasting on the sight, sound, smile, touch, smell, and signature of artist upon artist upon artist. For it is also like a giant autograph party in which the teen agers are outnumbered by middle-aged moms and pops. The fans' favorite part of it, obviously, is, as a Missouri woman put it, "maybe the best chance you'll ever get to see them up close, shake hands with them, have your picture taken with them-if you can fight your way through the crowd." It is difficult to tell whether the performers enjoy this mingling all that much, although they smile all the time and would say, in public, yes, they do.

But we do know what Sigmund Freud said the goals of the artist are, and I doubt he'd have taken it back had he guessed how Nashville would use the word artist; their goals, he said, are money, fame, and beautiful lovers. I don't have to tell you that some artists, a lot of artists nowadays, consider signing autographs for grown people and making small talk and grinning at Instamatics a pretty tame way of moving toward those goals.

But in country music the artists court right back when the fans make overtures. Or before. The Fan Fair is a concentrated place where, wildly outnumbered, they court back pretty hard. Artists were beaming and hugging chubby ladies from Arkansas and Wisconsin while Instamat ics and Pocket Instamatics clicked and flashcubes whirled and blasted, whirled and blasted. Jim Ed Brown stood up on the desk at his booth so fans could see him better; another artist's fan club was offering free memberships, no dues at all, limited time only, you understand, to anyone who'd come by and sign up; even Roy Acuff, the King of Country Music, had stopped by to sign programs, I was told, for those pure enough in spirit (they did not include me, alas) to crawl out at a decent hour and get down to the shindig early. Ernest Tubb, swamped by a hundred each of cameras and persons around his booth, demonstrated a remarkable ability to detect when any camera was about to go off, flashing his famous Texas grin in the nick of time.

--- " Nashville ... long ago dubbed its Opry 'The Mother Church

of Country Music'."

Most of the fair was held at the Muni cipal Auditorium, apparently because it has a larger seating capacity than, say, the new Opry House at the new amusement park, Opryland. The new Opry House was the site, however, of the very first Fan Fair program, the bluegrass show, and the last one, a fiddlers' con test. Downtown, the record companies took turns putting on shows from ten in the morning until midnight for two days and then until late afternoon on Saturday, the Opry itself being available for its usual two sittings on Saturday night.

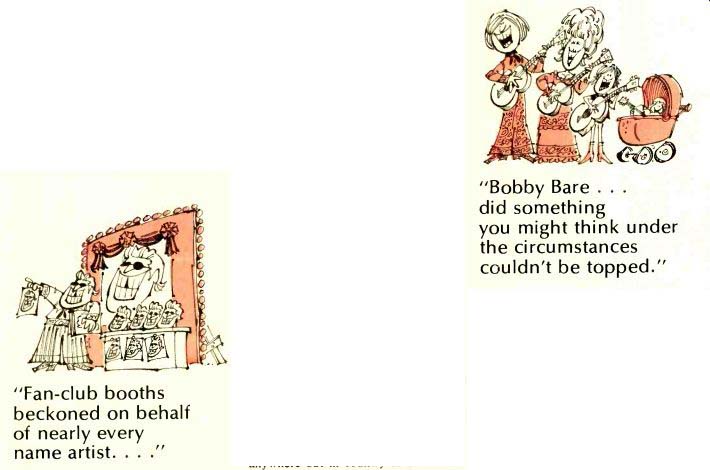

The basement of the auditorium was where the fair's uniqueness lay, though, where the booths stretched out farther than you could throw a cob, and banners were unfurled, baubles glittered, pretty girls smiled, little hurt. Fan-club boc half of nearly every 5, n eral non-name artists \ s ents had to dig to remea […] Delaney was, but their kid, with her name on them), ai where, any minute, a Big Favo, stop by for an hour or so of aut.

ing, chatting, and posing close-hug with anyone nervy enough to ask.

was where dreams were realized in th, flesh, and where a certain, relatively pal try, amount of disillusionment was suf fered having to do with hairpieces and wrinkles. This was where courage was … ." worked up, gods were approached, re quests were blurted out, grins were grinned, and trinkets (a Tom T. Hall Sneaky Snake, for example, or a heavy duty Faron Young shopping bag or a dancing wooden doll with your choice of an Archie Campbell face or a Grandpa Jones face) were bought cheap or, at the rare booth, acquired free-the best I could do in that area were some Tompall and Waylon stickers for my guitar case and a raffle coupon that might win me a Japanese pickup truck.

------- "... a remarkable ability to detect when any camera was about to go off ..."

Free buses ran from the auditorium to Opryland, to the Hall of Fame, and to the old Ryman Auditorium, former site of the Opry, near as tacky a Broadway as ever belted an Athens of the South. A young man with the gentle demeanor and new clothes of a deacon was there to help the bus riders keep it all straight.

"As soon as that bluegrass show is over," he said that first day, "you get back to Area Three of the parking lot. I mean go straight back; don't piddle around the Opryland gift shops or you might miss the last bus." As it turned out, there was time for piddling, as some of the acts, including Lester Flatt (who was about to undergo open-heart surgery), didn't make it. But Bill Monroe and his Bluegrass Boys were there, and Bill's son James and his band were there, and that seemed appropriate, with Father's Day approaching. James showed he can pick the guitar, too, and Bill sent the first chills scraping along from coccyx to coiffure when he introduced Kenny Baker as "the greatest fiddler in bluegrass music" and, with some magnificent back-up runs from Baker, tore into Muleskinner Blues, which he's been doing since 1939.

Opryland is a theme park, "the home of American music," providing periodic live performances of various popular musics in appropriate settings (a "New Orleans" area for Dixieland, and so forth), and of course has an assortment of rides and things to shoot and throw at.

The place can park 8,000 automobiles at a time, is lavishly landscaped, and is as neat as a pin, its walkways and crannies constantly patrolled by girls with sunny "Fan-club booths beckoned on behalf of nearly every name artist ... " olive uniforms, nice legs, dustpans, and broom-like things. All this from one little old radio show ... although, if you really want to talk history, the whole powerful country-music industry owes much, many personal fortunes as well as heritage, to an insurance company; it was National Life and Accident that put WSM into operation on October 5, 1925, and the station put the Grand Ole Opry on the air as soon as possible, November 28 of that year.

The record company shows started with Columbia's at ten o'clock in the morning, not one of my best hours but not an unusual one for Charlie McCoy, the legendary harmonica player and almost-as-legendary leader of studio sessions; he usually starts his day that early.

Wearing an off-white leisure suit (it was a big summer for leisure suits, you may recall) and a railroad cap, McCoy guided a band of studio cats through a tricky series of break swaps and key modulations--and the truth is no other band I heard during the fair was as tight as this one, or as willing to take risks. "I like being here among my heroes," McCoy said, and played his extraordinary, wind-breaking version of Orange Blossom Special. Young fellows like David Allen Coe and Eddie Rabbit showed what the new breed of country star is like- heavily influenced by Waylon Jennings is what he seems to be like-and Bob Luman demonstrated playing an un-miked guitar.

And there was Connie Smith, with her fine, clear, robust voice and her religion; later that night I heard her tell Ralph Emery on WSM that she no longer testifies every time she gets up on stage, "but every other song I do is a religious one and if it bothers folks that probably means the spirit of the Lord is getting to them." And there was Buck Owens with the power of television behind him, hit ting the stage in a burst of energy and selling, slicker than a lightning-rod sales man, a set plainly based on old rock-and roll songs such as Roll Over Beethoven and Johnny B. Goode. It seemed to mat ter less what Buck did than what Buck clearly is, an earthy, witty old country boy who always seems to enjoy himself.

Bobby Bare, during the RCA show, did something you might think under the circumstances couldn't be topped. After singing a Billy Joe Shaver tune and Mel Tillis' famous Detroit City (which Bare mostly made famous), he brought out, to sing one song each, his wife Jeanie, his daughter Carrie, his little son Bobby Junior, and his tiny son Shannon. After they'd wrapped it all up by singing, together, Singin' in the Kitchen, the audience thundered and thundered and the announcer was moved to comment, "You'll never see anything like that anywhere but in country music. You'll never see it in rock, I'll guarantee you." But nobody topped Loretta Lynn her head fans, the Johnson girls, are more famous than a lot of performers who've had hit records-for she had two booths operating on her behalf downstairs and the biggest crowd down there of anyone.

During an International Fan Club Organization banquet, to which ladies wore what in that part of the country are called "formals" and gents pretty much stuck with leisure suits, it was an nounced that Loretta had won one more thing, a popularity poll conducted by Music City News; her frequent duet partner, Conway Twitty, was the readers' favorite male vocalist.

And nobody really upstages Chet Atkins, either. All he did was pick a little to loosen up and then tell the folks, "We're comin' up on the Bicentennial, so I'm going to play you a little patriotic med ley," and all he had to do then was make sure he started it with Dixie. Still, that wasn't really all he did; a childhood so poor as to include malnutrition lies in his background, and that kind of qualifica tion never completely stays out of the way a person plays a guitar. And Jerry Reed was too busy playing the devilish egomaniac ("You ain't heard nothin' yet-- I'll have you throwin' babies up in the air . . ."), too busy shooting up on the folks' laughter, to notice who was upstaging whom.

"Bobby Bare . . . did something you might think under the circumstances couldn't be topped." The most sentimental stage show was a first-time feature called the Reunion.

Pee Wee King sang Slowpoke and introduced Floyd Tillman, who wrote Slippin' Around, and Ray Whitley, one of the first Hollywood cowboys brought in to be on the Opry. Whitley was paid $350 for writing Back in the Saddle Again and helping Gene Autry buy all the saddles, boots, pickup trucks, jerky, and baseball teams any old cowpoke could want. Joe and Rose Lee Maphis (parents of Jody, Earl Scruggs' drummer) did Hot Time in Nashville, mainly an excuse for a blazing fast solo by Joe on his double-necked electric guitar. Minnie Pearl introduced the Fruit Jar Drinkers, regulars for all the Opry's fifty years, and Alcyone Beasley, the Opry's first female singer, and Fiddlin' Sid Harkreader, seventy seven, who played a tune he made famous during the first year of the Opry, Mockingbird Breakdown, and drew a great, emotional roar from the crowd.

"Bless his heart," Minnie said, and then caught us up on news of her kin: "Uncle Nabob's corn crop was so bad he didn't get but five gallons to the acre." Lulu Belle and Scottie Wiseman, examples of stars who, in the old days, came to Nashville after making names for themselves at the WLS Barn Dance in Chicago, did their celebrated song, Have I Told You Lately That I Love You. Grandpa Jones and wife Ramona were there, and Clyde (Shenandoah Waltz) Moody, Jimmy (Let's Say Good bye Like We Said Hello) Skinner, and the Bailes Brothers of Dust on the Bible Nashville fame, and there was Whitey Ford, the Duke of Paducah, still oddly sophisticated and corny at the same time. And there was much ado in tribute to the late Bob Wills, creator of country swing, big dance-band country (who managed to get a snare drum on the Opry stage, past the late George D. Hay, the Solemn Old Judge who ran things; Ford said nobody, in fifty years, has been allowed to use a full set of drums in the Mother Church).

Leon McAuliff, playing the pedal steel from a standing position, narrated the tribute, and a few of Wills' Texas Play boys performed: drummer Smokey Dacus, fiddler Johnny Gimble, vocalists Laura Lee McBride and Leon Rausch.

The Reunion didn't quite pack the house the way the record-company shows had, but it had the most intense, attentive audience I've seen at anything in a long while.

MANY celebrants, though, were still punishing their feet downstairs, trying for two or three more autographs. The circular shape of the basement area, the milling crowd, the colors and sounds, and such distractions as the golden tresses of Barbara Mandrel! combined to mess up one's sense of direction down there. I stumbled across an old friend, singer Marti Brown, whose little girl, Leah Ann, was flying an Ethel Delaney balloon.

"Now people are going to think I'm Ethel Delaney," Marti said. As we talked-about how many fans were in wheelchairs, which Marti noticed, and about how several of them were really quite tremendously fat, which I brought up-and as I talked to myself about how you don't see goiters on Southerners and Mid-westerns the way you used to, thanks to iodized salt, I noticed the passersby included Billy Swan and his song-writing pal, Donnie Fritts, known to some fans as the Alabama Leaning Man, sauntering along as ogle-eyed and rubber-necked as anyone else.

Heeding Marti's advice to check out Bill Anderson's booth, I wandered. I saw Jeanie C. Riley in a long dress (no more Harper Valley miniskirts for her!) and running around loose, out of her booth, and holding hands with a dude almost as shaggy as Tompall Glaser and Waylon Jennings have become lately; saw Danny Davis, leader of the Nashville Brass and a great favorite with the photographers or editors or somebody at Music City News, standing alone and temporarily unrecognized; asked Mc Coy if he'd tried the new Golden Melody harps and was told he liked the case they come in; saw where one could ac quire Jerry Reed's "I'm a Coonass" stickers that were plastered everywhere; caught a glimpse of Tanya Tucker, whose club had brought in a replica of a rumble-seat roadster as a prop relating to one of her songs; went out for some fresh air and saw Jerry Clower in a yellow (double-knit but non-leisure) suit about to be approached by seven per sons on the streets of Nashville; ducked back in for the drink in Municipal Auditorium, a Pepsi, and finally found it.

The booth was impressive, designed to represent an old cathedral-style radio with the grille cloth removed so you could see Bill Anderson (famous for Po' Folks, of course, and recently as the writer of the outrageous Between Lust and Watchin' TV) and his trusted aides inside it. But it was the little sign beside the booth that got my attention, and not the content of that but something in the style of the lettering. Now where?...

Ah, yes, in a department store: it was that odd, shy kind of lettering they use on the little signs in department stores, such as. . . . I read: "Bill Anderson and J. C. Penney welcome you to the Fan Fair." And under that: "Bill Anderson's wardrobe by J. C. Penney." Well! That is the interior of the country for you, isn't it? But hold on, now; Bill's threads looked all right, as good as "Bill Anderson and J. C. Penney welcome you to the Fan Fair." Johnny Miller the golfer's Sears duds and as good as my Levi's. Anderson is a fastidious fellow, never a hair out of place, all fingernails the same length and immaculate and that sort of thing, but this isn't just a case of someone wanting to put on the dog and not knowing where the fancier dogs are kept. Neat and clean is the thing, not the label; people who get dirty doing their work-and most Middle American jobs get you dirty-like his kind of crinkly fresh cleanliness on a holiday. The stars do dress to please the folks, of course, but they also dress as they do because they are the folks. Bill Anderson's were po' folks; like most pickers, he came from amongst what are now your television watchers and bowlers, farmers and shopkeepers, coon hunters and good old boys, the Elks, the Eagles, and the Odd Fellows.

These are survivors, not tastemakers.

The Fan Fair does teach a little some thing about how country fans have changed-about the acceptance of long hair and beards and other such liberations; hell, the truck drivers are sporting whiskers these days-but it seems to teach more about the similarities, the constancy of country fans old and new. I think this lesson involves some kind of bent physics impregnated with sociology that seems to postulate that the land, all that distance from the sea, somehow soaks the urgency out of incoming messages (concerning man's cosmic predicament or, for that matter, his measly triumphs) before they reach these hinter lands. I do not know how the land does this, defies the television and electronics we've been led to believe are instantaneous and leveling and unstoppable, but the land always has been quite some thing. I do know there's more optimism back in there than you'll find on the coasts. They know about the corruption and the downturn of economic indicators (including a slight dip in country record sales) and they don't claim to be smarter than the slick politicians, but they also seem to know there's strength in being a Miasma of Methodists, as Mencken called a high percentage of their grand parents; these other matters are just too short-term to fool with much. They watch Cronkite, but they don't treat the news of the day as some kind of damned bottle to suck on. So it's about as easy to find a genuine pessimist at an affair like the Fan Fair as it is to find someone who'd rather discuss abstractions, ideas, than something he can feel and see and, better still, manipulate, such as a car. A man and a woman (it usually takes both, still, so they still tend to stay married) can manipulate the land to an extent, order their relationship with it when the weather permits, while their seaboard cousins can't do much with the ocean except fish in it and contemplate it, which is bound to lead to abstractions because the thing is so big and mysterious, and in all this stuff may lie profounder influences than we realize.

The best thing about the Fan Fair, one may then say, was that it showed America's regions still working. The development of the nondescript, general, grey hybrid culture is not zinging along at the clip I had thought it was. We may yet pass 1984 with a little diversity still in us.

At least they haven't taken all the country out of the country fan. True, there don't seem to be many old-time, hillbilly-style, actual genuine hicks left, at least not out on air-conditioned pilgrim ages. But back in Ohio and Tennessee and Fitchburg and Sleepy Eye, they've still got some folks.

--------

...flawed in the worst place a movie about Nashville could be"

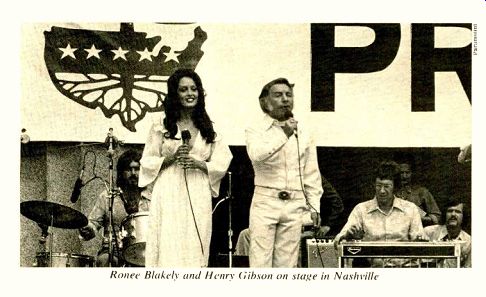

Ronee

Blakely and Henry Gibson on stage in Nashville

And Then There's "Nashville"

IF you get your media from New York, and if Dr. Pavlov's experiments meant any thing at all, then when I say "Robert Altman's Nashville," the word "Masterpiece!" should explode in your mind like the Shea Stadium scoreboard going off when one of the Mets hits a home run. You've had the kind of conditioning people used to think should only hap pen to a Russian dog, but which is not all that unusual nowadays. The New York-based, New York-biased movie critics haven't gone around the bend like this (that is, together, or, as some might put it, in a pack) on a movie since ... well, since Peter Bogdanovich's The Last Picture Show. You will probably be able to remember The Last Picture Show if you can slip into a black-and-white mode of thinking about another non- New York place, Texas, and concentrate about medium to medium-well.

One can understand it, though: Robert Altman probably is the one American director capable of a masterpiece. In fact, he may al ready have come at least as close to that as Citizen Kane did-but it wasn't Nashville, it was McCabe and Mrs. Miller. Now there the overlapping dialogue, the unobtrusive precision of the television-documentary-style camera work, and Altman's fondness for a "natural" episodic, nonlinear replacement for beeline plot all worked together beautifully, and the central theme was of classically tragic proportions . . and the evocation of it was so understated yet concentrated, so robust yet elegant, that the pain of it may actually stick with me the rest of my life. Individual critics here and there praised it highly, but they never ganged up for a concerted push, and the public wouldn't or couldn't deal with McCabe in significant numbers.

But Nashville's social implications-since it deals with Making It and (new wrinkle) not only that but Making It in a Middle American City-are easier and a lot more fun to write about than are McCabe's sad conclusions about each person's essential isolation, and before a political science professor could jerk his knee the Opp Ed writers, such as Tom Wicker, started getting in on it, rambling on about stock-car racing and other signs of America's "heedless vitality," got to admit is kind of a cute phrase. The right wing played its part too, with a surprising piece extravagantly praising the film in Wil liam Buckley's National Review.

So far, you say, this is sounding dreadfully familiar: New York has elected something new to celebrate and here we go again, and at least Cybill Shepherd isn't in this one. But I, perhaps under the influence of Altman's anti-storytelling technique, have let us get ahead of ourselves. Altman being Altman, you don't want to be reactionary and prejudge the thing (even though that will save you a lot of time if you have to deal again with Bogdanovich or Mike Nichols or other recent Big Apple anointees). We had the subject and the director for something extraordinary, I kept think ing, recalling the feeling for authenticity at which Altman excels-how depressingly muddy the Korean mud was in M*A*S*H, or how bloody the blood was, and how absolutely convincing the deep-bogging Northwest snow and the under-construction frontier village were in McCabe. The connective tissue for a movie about making it in Tennessee of course is country music, and if Altman could get that right the way he had gotten visual connectives right in other movies ... well.

WELL. The first jolt was the ABC Records soundtrack album, which came to my town before the film did. The collection of songs and performances sounded like some kind of parody of country music (except in one or two cases involving Keith Carradine, who's sup posed to be doing folk-rock, or something vaguely like it). The tone of the reviews and columns had led me to expect songs and performances that represented country music (that were as good, bad, and mediocre as it really is and which, individual aesthetic differences aside, could be taken easily enough for the real thing), to expect--Altman being Altman-the ring of authenticity. The sound track album, if that were the case, should stand up with other country anthology albums (Epic's "Country 45's," for example) and hold its own, for the movie was supposed to be that important. But alongside albums like that, the soundtrack was not only aesthetically inferior, it sounded amateurish, dated (in the uninformed sense), and everywhere superficial, as if made by outsiders and Johnny-come-latelies.

Still, there was the question of how the film intended to use the music. It was possible it had to be this way, somehow, for the story to be told. But seeing the movie didn't convince me it had to be that way. Nashville turned out to be visually superb, an object lesson, technically, in how to handle complicated scenes on location, and it did seem that the words, at least, of some songs did relate to the story images in fairly subtle ways typical of Altman-but there is no getting around the fact that the movie is flawed in the worst place a movie about Nashville could be flawed: in its music. Anyone reasonably familiar with the music Nashville actually makes will find himself having to make too many al help the movie too much, during the music scenes. The actors and the songs they themselves mostly wrote are almost never very convincing in such scenes.

ALTMAN has shown the bias that prevails every day in high-school and college theater productions, the idea that acting is more difficult than anything else, the idea that leads to trying to get music out of actors when it might be more sensible to try to get acting out of musicians. Without getting into just how much we may have romanticized and consequently overrated acting, it is an inescapable truth that we all do a little of it almost every day, every time we weasel out of an invitation and don't give the real reason, every time we appear (starting in the second grade or earlier) interested in some subject that bores the hell out of us, and so on. But we can't all sing, and very few of the mediocre singers among us could pass ourselves off for a minute as established professionals who've been making a good living at singing for a long time. It was considerably easier to make allowances for John Denver's acting in an episode of Mc Cloud, for example, than it has been to tolerate, let alone believe, Dennis Weaver's so called singing in two or three subsequent variety shows and an awful single or two.

Television (where Altman got his start) routinely operates on the assumption that "any body can sing," meaning Lorne Greene, Telly Savalas, Sammy Davis Jr., anybody (television even assumes Jack Palance can play the harmonica), but television is only doing in quantity what the movies--perhaps drama itself- started a long time ago. Surely you remember those awful scrapings wrung from the throat of Gene Kelly.

Nashville has tried toying with that assumption a few times, but it has never really stuck. Nashville's music works only occasionally, even as part of the non-plot--the song that precedes the climactic killing scene, Ronee Blakely's My Idaho Home (probably the best of her songs in the bunch; at least it sounds as if it is based upon real memory in stead of adopted character memory), does fit as only a piece of "original material" would.

Karen Black, of all people, wrote the one song, Memphis, that might be taken (if you used the old test of waking up a country fan in the middle of the night) for a current product of Music Row. For the Sake of the Children, written by Richard Baskin, the film's music arranger, and by someone identified as R.

Reicheg, isn't too bad, but it sounds like a country song of twenty years ago, and Con way Twitty alone, with his tricky new re-castings of the eternal triangle, has made such simplistic treatment of the old generalities obsolete.

IMILAR small bad judgments abound:

Henry Gibson, playing Haven Hamilton, "the king of country music," introduces Keep a-Goin', which he and Baskin wrote, and what he says about it leads you to believe it is the song that made him, years ago, and is the one fans still identify with him. But it turns out to be one of those quickie throwaways of the sort producers keep finding for Olivia New ton-John. Country audiences back when grey-at-the-sideburns Hamilton made it-which would be vaguely relative to the time when Roy Acuff, the real-life "king," made it wouldn't have clung to such a song in a steady, tradition-cultivating way, as they glommed onto The Great Speckled Bird. The tune (for the purposes of our story, anyway) might have been a mild hit forgotten in two weeks, but it simply could not have been the trademark of the genre's Big Honcho. Blakely, the only actor-writer-singer with appreciable experience at writing and singing in places like coffee houses where they don't assume anybody can sing, makes a pretty good start on a country feeling with the title Tapedeck in His Tractor, but as soon as you learn it's a sod-busting tractor instead of the kind on the front of a semi, she's got problems. It goes into a rambling, nonsensical refrain about cowboys-"He was a cowboy and he knew I loved him well,/A cowboy's secret you never tell . . ."--and your attention scatters like buckshot. First, the mind has to go through the farmer-cowboy business; plowing is not something a cowboy does. She's not necessarily wrong, since it's self-image or girl friend's image of boyfriend she's dealing with, but real country songs don't leave you wondering how to define the terms like that. And then, what is this stuff about a secret? The song just leaves that hanging, and country songs don't do that, either.

And where a Nashville song is passable, the singing is not. The backing is fine; they used real Nashville studio musicians for that (Vassar Clements even manages a lovely break on a Karen Black song, Rolling Stone, that is itself the absolute dregs), and Nashville studio musicians may be the best musicians in the world, a major reason why there is a Nashville, something Altman perhaps should have given more thought to before starting the project. The star system, something Altman didn't miss, does thrive in Nashville, though, and the singers are the stars. The real ones may be good by any standard (Marty Robbins could hold his own anywhere in a vocal-instrument one-on-one) or as singing is generally evaluated they may be terrible, but they all have something an actor cannot be expect ed to develop in a brief rehearsal period, and "Karen Black, of all people, wrote the one song that might be taken for a current product of Music Row." that's style. Country singers are passionately aware of the need for sounding unlike anyone else. Once they manage to do that-and it may be already built-in by nature or it may take them years-they take security in it, and that helps everyone relax a bit even when this personal trademark sound is, if you analyze it, grotesque. The movie singers are clearly faking it (except for Blakely, whose shaky, trans parent sound, like her writing in such decent but not-quite-appropriate songs as Bluebird, belongs to a folkie-type who might be better cast in a picture called The Troubadour or Mariposa), and even when Black isn't making a complete mess of anything approaching a low note or when Gibson isn't putting a corny wave in his phrasing that he must have picked up from the groaning in minstrel shows, the absence of stylistic security can be heard. It reminds you this is a story, this is pretending.

Carradine fakes it better than the others-he doesn't quite represent country music, for one thing, but mainly he benefits from being able to play the guitar, which solves the hands problem. A real country boy has trouble growing out of the anxiety concerning what to do with his hands in a public, polite place. The movie "king," old Haven, sings standing stock still or walking around holding the mike, but real country stars-male ones, that is use instruments (among other things) at least as props. The real "king," Acuff, plays the fiddle, after a fashion, or sometimes he will do yo-yo tricks, and as the song ends he likes to balance the violin bow on his nose.

NASHVILLE is a good movie (as was The Last Picture Show) in view of how much pre tending we have to do to help other movies along. Altman's attention to the visual details serves it well (although I think the edited version we get to see could have used some shots of Church Street, downtown, one of the "other" Nashvilles), and nowhere does he botch the job the way other directors regularly do.

You will perhaps recall that Fear Strikes Out had Anthony Perkins, who is a pretty good ac tor but who throws like a girl (the way girls used to throw, anyway), playing Jim Piersall, who probably had the best throwing arm of any outfielder then in the American League.

Altman's "singers," who are supposed to be able to carry a tune, do come reasonably close to carrying one. It's the understanding of subtle truths about the music itself that fails, and one of the results is that the movie appears intentionally or not-to be saying something on the side about how cynical all Nashville is about the music itself. There is plenty of cynicism in that city, of course, and the Middle Americans who populate the area do look more gawky and awkward than New Yorkers and Californians in the act of practicing the Big Hustle. But the music is taken seriously a reasonable percentage of the time (how else could the studio sidemen have gotten so good?), and when Loretta Lynn defends her decision to record a song like The Pill she is either genuinely exercised and wide-eyed or she is one hell of an actress. And I don't think Altman-unlike some of the critics and columnists-is merely out for the sport of beating up on the New Kid; he does not have a reputation for cheap shots.

No, I think Nashville is to Altman as Sanctuary was to William Faulkner, a contrivance containing a little bit of everything and designed to attract a lot of attention and make a lot of money, which should have the effect of getting the really dangerous hustlers-the so called businessmen who run the industry-off his back and, in the process, garner a little more attention for the rest of his work. I don't say Altman designed it that way consciously, as Faulkner said he did with Sanctuary, but I do have some hope that Nashville may do for McCabe and MASH what Sanctuary did for Absalom, Absalom and As I Lay Dying.

- Noel Coppage NASHVILLE (Robert Altman). Original-soundtrack recording. Ronee Blakely, Henry Gibson, Timothy Brown, Karen Black, Keith Carradine, others (singers); Troy Seals, Harold Bradley, Weldon Myrick, David Briggs, Vassar Clements, Johnny Gimble, others (instrumental accompaniment); arranged and supervised by Richard Baskin. It Don't Worry Me; 200 Years; Bluebird; Memphis; For the Sake of the Children; Keep a-Goin'; Rolling Stone; Dues; My Idaho Home; Tape-deck in His Tractor; One, I Love You; I'm Easy. ABC ABCD-893 $6.98, 8022-893 H $7.98.

--------

Also see:

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)