THE OPERA FILE by WILLIAM LIVINGSTONE

THE BOLSHOI: ON STAGE AND ON DISC

HE announcement that Hurok Concerts was bringing the Bolshoi Opera here from Moscow this summer for the company's first visit to the United States did not send opera fans running through the streets gleefully shouting "The Russians are coming! The Russians are coming!" We had gotten all excited about such announcements several times before, and the Russians invariably canceled.

The Bolshoi Ballet, which preceded the opera company, dampened enthusiasm with their very disappointing season-ugly sets and costumes and abysmal new choreography. Then, too, aside from Boris Godounov, Russian opera has never been popular in this country, and aside from the impressive basses, Russian singers' voices often sound acid and edgy to Western ears.

By the time the tons of scenery began to arrive and it was certain that the Russians did intend to fulfill the engagement for four weeks of performances at the Met and two weeks at the Kennedy Center in Washington, it was also clear that we were entering the most oppressively humid summer in many years. Like most other New York opera fans, I consequently looked at the Bolshoi performance schedule with something less than maximum enthusiasm, and it did not even occur to me to go to the airport to greet the arriving company of 450 soloists, choristers, supers, stage hands, orchestra members, and conductors.

But now that it's all over, I wish I had made some such extravagant gesture, because I'm never going to be able to thank them enough for those four weeks of fascinating performances. I was genuinely surprised that I liked them so much, and I couldn't seem to get enough of them. They brought productions of six operas from their own national repertoire:

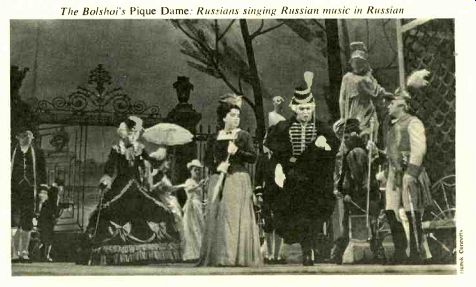

Moussorgsky's Boris Godounov, Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin and Pique Dame (The Queen of Spades). Prokofiev's The Gambler and War and Peace, and a brand new opera by Kiril Molchanov, The Dawns Are Quiet Here. The opportunity to see any one of them without having to go to Moscow would have been an occasion for rejoicing, but they brought six! All the performances I attended were distinguished by an overwhelming sense of stylistic authority about direction and production details right down to the last prop. And down to the last super the performers looked absolutely right. Why not? They were Russians playing Russians and singing their own music in their native language. The Bolshoi chorus is the best I have ever heard-how they made the rafters ring in Boris Godounov and War and Peace!-and their orchestra and conductors are topnotch.

----------- The Bolshoi's Pique Dame: Russians singing Russian music

in Russian

The Bolshoi is a great ensemble company, and in their New York performances the overall level of acting was extraordinarily high, especially in the small character parts. It was as though every single member of the company felt that his contribution, no matter how small, was vital to the performance, and every once in a while you could spot a major soloist in a tiny role. The leading baritone Evgeni Kibkalo, for example, turned up as one of five Jesuits on stage briefly in the Kromy Forest Scene in Boris.

The names of a few of the fifty-seven principal singers listed alphabetically in the pro grams were dimly familiar from Melodiya recordings, but most of them were unknown quantities. After a week or so of performances it became clear who the stars were.

Public favorites in New York were the mezzo Elena Obraztsova, who had a big success as Marina in Boris Godounov and other roles, the tenor Vladimir Atlantov, who has a surprisingly Italianate voice and temperament, and the baritone Yuri Mazurok, who is simply fabulous.

I now think Russian sopranos have been unjustly maligned in the West. The Bolshoi's prima donna, soprano Tamara Milashkina, has a definite Slavic tone color, but it's not hard on the ears, and it sounds quite idiomatic in the Russian operas. As for those impressive basses the Russians are famous for, they seem to have run out of them for the moment.

Although very convincing dramatically, the ones who sang the title role in Boris Godounov here did not come up to the vocal level we expect in the West.

I am not fond of Boris--I don't like operas with no real love interest, operas in which the actual protagonist is something like the city of Paris or the people of Russia-and I had al ready done my duty to Boris this year by at tending the Met's acclaimed new production with Martti Talvela. Nevertheless, despite some vocal shortcomings, this Russian Boris was one of the most enjoyable operatic performances I've ever seen. I felt completely transported in time and space. You could almost smell the incense in the cathedral. Hurok's ads for the Bolshoi season said, "There is nothing in the world to match the splendor and scope of these magnificent productions." I wouldn't go quite that far, but the Boris was good support for the claim.

I feel more strongly about the Tchaikovsky works-Pique Dame is my favorite Russian opera-and I was fortunate to hear it sung by Milashkina and Atlantov and to hear them with Yuri Mazurok in Eugene Onegin. Vocally, dramatically, and visually, Onegin was the best of the six works the Bolshoi performed here. It looked like a lovely Chekhov play, and the company acted it that way.

Prokofiev's War and Peace blew my mind. I have not taken so much delight in discovering a twentieth-century opera since my first Turandot-at moments it is reminiscent of Turandot. I never knew Prokofiev had writ ten so lyrically for the voice, and I was moved by the big patriotic scenes, which some people found propagandistic. In reviewing an exhibition of nineteenth-century French history-painting at the Metropolitan Museum this summer, art critic David Bourdon wrote: "One of the revelations of the show is seeing how much blatant propaganda a painting can successfully sustain." I submit that War and Peace is a great enough work of art to sustain any amount of propaganda. It was not a Communist tract, but an expression of the Russians' love for their country, and it made me wish native faultfinders would allow us the luxury of such patriotism in this country.

An opera that cannot sustain its burden of patriotism and propaganda is The Dawns Are Quiet Here, which is about an all-girl (!) anti aircraft unit in World War U and the noble deaths of four of them. It reminded me of all those 1940's war movies on late-night TV-Veronica Lake in So Proudly We Hail-and Molchanov's score sounded like a very efficient movie soundtrack. Though it was interesting to learn what a new Soviet opera looks and sounds like, one was quite enough.

With the exception of The Dawns, the Bolshoi visit was cultural exchange of the finest kind, and as my excitement mounted, it seemed there were Russians everywhere.

Right next door to the Met. at the State Theater. the American Ballet Theatre was presenting such defectors as Rudolf Nureyev, Natalya Makarova, and Mikhail Baryshnikov.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn was in town warning Americans of the world-wide danger of Soviet power. Out in space Apollo astronauts were meeting the Soyuz cosmonauts, and an exhibit of paintings from Russian museums opened at the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

I am told that Washington's music critics took a unanimously positive view of the Bolshoi Opera. New York's critics were divided.

Harold Schonberg and the others who re viewed the company in the Times were rather cool to the Russians and wrote guarded or picky reviews that I found, well, mean-spirited, and in New York magazine Alan Rich seemed almost hostile. The Bolshoi was championed in the New Yorker by Andrew Porter. who got sufficiently worked up to list aria titles not just in Russian but in Cyrillic type, and by the Post's critic Harriett John son, who seems to me more and more the one who really calls the shots on vocal music.

I got sufficiently worked up to listen to all my Russian opera records again. Although there is no substitute for seeing productions like the Bolshoi's, you can get a very good idea of the way they sound from discs. You could start with a single disc, "Stars of the Bolshoi" (Melodiya/Angel SR 40050), but only one side is excerpts from Russian opera, and Milashkina, Atlantov, and Mazurok are represented only by excerpts from Aida, Pagliacci, and Faust. If you are willing to gamble on a complete opera recording, I would recommend first the Bolshoi's Eugene Onegin (Melodiya/Angel SRC1 4115) with Vishnevskaya, Atlantov, and Mazurok, conducted by Mstislav Rostropovich. It's excellent. So is War and Peace (Columbia/Melodiya M4 33111) with Vishnevskaya, Kibkalo, and many others, conducted by Alexander Melik Pashayev.

The complete recording of either Onegin or War and Peace will cost you about the price of a ticket to a Bolshoi performance and will repay your investment for years. Hurok Con certs cannot have made money on the Bolshoi's visit (they charged only $10 more than normal Met prices for an orchestra seat), and it is generally supposed that the agency under wrote the Bolshoi visit for reasons of prestige.

It was the dream of the late Sol Hurok to bring the Bolshoi Opera to America. He died March 5, 1974. I wish he had lived to see his dream come true. The Bolshoi's visit made me glad I'm alive, well, and living in New York.

Also see:

THE BASIC REPERTOIRE, MARTIN BOOKSPAN

THE SIMELS REPORT, STEVE SIMELS

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)