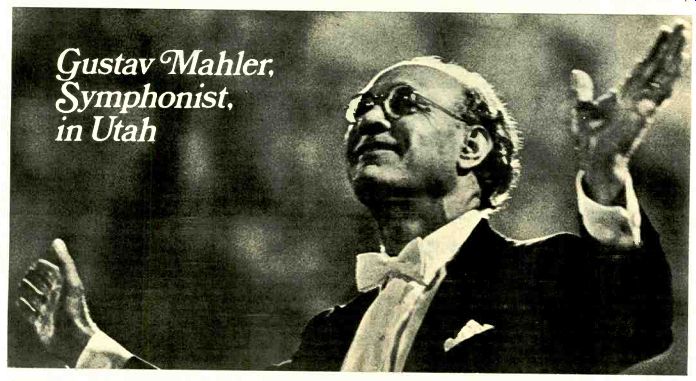

THE UTAH SYMPHONY'S MAURICE ABRAVANEL: "You know, there's a lot of snobbery

around music circles"

By Roy Hemming

THE excitement was clearly evident in Maurice Abravanel's voice. "Yes, we are the first American orchestra to have recorded all the Mahler symphonies. And I've just received the news that our complete set has been chosen by the largest record club in Switzerland and Germany as the one it will offer.

That is quite an honor for us. I'm sure they could have made as good a deal for the recordings made by orchestras and conductors that are much better-known in Europe. But they chose us-from Utah. I am most happy." Abravanel's Mahler recordings with the Utah Symphony Orchestra have stacked up a number of other firsts. Not only are they the first all-American set (Bernstein's and Solti's were both re corded partly in America, partly in Europe), but the Abravanel-Utah versions of Mahler's Seventh and Eighth Sym phonies were the first studio recordings of these mammoth works by anyone (earlier releases had been based in whole or in part on live concert performances in Europe).

For Abravanel himself, the Mahler cycle marks the culmination of a love affair with Mahler's music that goes back to his youth. "I first heard Mahler in Berlin when I was nineteen," the tall, wiry, seventy-two-year-old maestro recalled recently in an interview in New York.

"It was in 1922, when Mengelberg con ducted Das Lied von der Erde. I was absolutely struck by it. A short time later, I heard the Eighth Symphony. That did it! I fell in love with Mahler and promptly went out to buy every score of his that I could get my hands on. I was just a kid, a student in Berlin, and I went without lunches for three months so I could buy those scores." Berlin in the 1920's has other vivid memories for Abravanel, memories of events and encounters that were equal ly influential in his career: it was in Berlin that he first met and studied with Kurt Weill and Bruno Walter. "Bruno Walter helped me a great deal 'way, 'way back, and he was the one from whom I learned Mahler," Abravanel said with the combination of warmth and animation that marked almost all the comments he made during our interview. "Before I conducted the First Symphony for the first time, he and I went through the score as he sat at the piano. He would say to me: 'This is what Mahler told me.' It was an unforgettable experience. I think the things we learn when we are very young stay closest to us throughout our lives. They're in our blood." How then, I asked, would he compare his approach to the Mahler symphonies with those of Bernstein, Solti, Haitink, or others who have also recorded complete sets? Abravanel seemed a bit reluctant at first to answer, but then plunged in. "We are all different because we are different men. I'm not as theatrical as Bernstein-although that is certainly a great and special quality of his; in my book he is a genius. I think I'm more of a romanticist in the traditional sense than some of the younger conductors who have also recorded Mahler. I learned the tradition from musicians who knew Mahler and worked with him. I think I bring that to the music.

"Today there are many conductors who play just the notes [of any piece], which was the prevalent idea Stravinsky peddled from the 1920's on. I believe a performer must put all his heart and soul into whatever he does. The combination of the composition and the convincing performer--this, to me, is music. I agree with Gide when he talks about the 'part of God' in art. One always does more than one thinks he's doing. I believe there exists for every artist-whether a sculptor, an actor, or a musician--some thing beyond the technical ability, some thing in your heart."

For this reason, Abravanel is not particularly bothered by the fact that his Utah recordings "compete" in the commercial world with those of more famous orchestras led by more famous conductors. "When I perform Mahler, I know it is music that has long been a part of me, that I know well, and that I believed in long before many others did. So I do not feel I am 'competing' against anybody!" ABRAVANEL was born in Salonika, of an old Spanish family. "One of my ancestors was Don Isaac Abravanel," he says. "He was quite a guy in his time-a minister to Portugal at the age of twenty-one and then chancellor to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. He left Spain at the time of the Inquisition, al though the king asked him to remain.

One of his sons was invited by the Sultan Suleiman to settle in Turkey--to help lure trade away from Spain and Portugal, and also from Venice and Genoa, which he did very successfully." Eventually the family settled in Salonika, which was under Turkish rule at the time. "But our family traditions re mained Spanish. I remember my mother singing Spanish folk songs to me as a child. And she cooked Spanish." As Abravanel neared school age, his father, a pharmacist, moved the family to Lausanne, Switzerland. For several years the Abravanels lived in the same house as Ernest Ansermet, the Swiss conductor who later founded the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande but was then chief conductor for Diaghilev's Bal lets Russes. "Ansermet took me for my first sleigh ride!" Abravanel cries out, as if suddenly remembering a long-forgot ten joy. "And we used to play piano four-hands. He was an even worse pianist than I was! "I also remember piano run-throughs at the house with Milhaud for La Boeuf sur le Toit and with Stravinsky for L'Histoire du Soldat. Stravinsky came there often, as he lived about a five-min ute train ride from Lausanne. The first staged performance of L'Histoire, in fact, was given almost entirely with students from my school." Abravanel's own music studies began at age nine. "My sister had started piano lessons, as did all the dutiful daughters of middle-class families. I think I enjoyed her practicing more than she did. I was in love with the minor scale especially; I thought it was too beautiful for words.

The piano teacher was our governess, a very good-looking blonde from Munich.

So maybe that also had something to do with my eagerness to take piano lessons! "I would go to all the concerts I could as a teenager. I remember once riding on the back seat of a motorcycle all the way to Geneva-in the dead cold of winter to hear Lohengrin. I knew then that mu sic was my life. I think I also realized I was too dumb to do anything else! I had to be a musician or nothing." From Lausanne, Abravanel went to Berlin to study. "Someone recommend ed me to a brilliant young student of Busoni's--that was Kurt Weill. He taught me counterpoint and harmony." Over the next twenty-five years Abravanel's career was linked closely (though not exclusively) with Weill's. They left Germany together in 1933. "It was two weeks after Bruno Walter was forbidden by the Nazis to conduct." They went to Paris, where Abravanel became a conductor for the Ballet Balanchine for a year, leading, among other things, the premiere of the Brecht-Weill "ballet with song" The Seven Deadly Sins. He also helped Bruno Walter prepare Don Giovanni at the Paris Opera and alternated with Walter in conducting it.

He went to Australia with the British Covent Garden Opera company and stayed on there for two years as head of the Sydney Orchestral Society. He came to the United States in 1936 when he was invited to conduct at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and he remained at the Met for several seasons.

"I once conducted seven performances of five different operas in nine days," he says. "I think it's an all-time endurance record for the Met." In America he also continued his close friendship with Kurt Weill. "One of the first things I mentioned to Edward John son, who was then general manager of the Met, was that he should do one of Weill's operas. He was shocked. He knew only The Three-Penny Opera and felt it had no place at the Met." Weill, of course, went on to compose numerous works for Broadway-and Abravanel became music director for most of them, including Knickerbocker Holiday, Lady in the Dark, One Touch of Venus, The Firebrand of Florence, and Street Scene (the last has since entered the repertoire of the New York City Opera). "You know, Weill's style did not change as much in America as most people seem to think," Abravanel declares. "He was always his own man, writing his own way. He tried very hard to write 'Broadway music,' but he never really did. If you compare some of the music of One Touch of Venus, for example, with the Berlin pieces, you'll see that Weill was always Weill no matter where he was. He was a great human being as well as a musical genius." I asked Abravanel, since he's the conductor of most of the original-cast recordings of Weill's Broadway works, why he hasn't recorded some of Weill's purely orchestral works. "Frankly, be cause no one has asked me to record them," he replied, "but I've played the Second Symphony, the Violin Concerto, and the Walt Whitman Songs in Salt Lake City with great success." Abravanel's Broadway credits also include Billy Rose's Seven Lively Arts, a 1945 revue that mixed two most unlikely composers: Cole Porter and Igor Stravinsky. "It was a wild combination," Abravanel recalls. "And it had the most beautiful showgirls this side of heaven!" In the years following World War U, the Broadway whirl began to pall for Abravanel. "At first it was very exciting," he admits. "The concert life was fantastic in New York--the best any where. You could hear Bruno Walter on Monday night, Rubinstein on Tuesday, Koussevitzky on Wednesday, Fritz Busch on Thursday, Stokowski on Fri day, and so on and on, night after night.

You went from peak to peak. But after a while, you began to lose all perspective.

You could only remember how great something was for twenty-four hours until the next great concert erased its memory. I decided I wanted to settle down with an orchestra of my own somewhere away from all that." The Utah Symphony provided just that opportunity. Since 1948, Abravanel has been its music director-the longest permanent tenure of any conductor in America today other than Eugene Ormandy (who's been in Philadelphia since 1936). Over the years, Abravanel has built the Utah Symphony into an inter nationally respected ensemble, especially well-known for its more than eighty recordings for Vanguard, Angel, and other labels-many of them first recordings of works by such diverse composers as Handel, Grieg, Honegger, Gottschalk, Satie, Vaughan Williams, Mahler, and an American composer Abravanel believes deserves a much wider hearing, Henry Lazarus.

"Music should be a counterpoint to the time in which it is created.

All this talk about`relevance' is wrong." At a time when more and more conductors seem to be splitting their time between two orchestras, Abravanel insists that he is monogamous. "Even in Mormon territory I believe in one wife and one orchestra. It is my life's blood. I love every member of the orchestra." The orchestra gives about one hundred eighty concerts over a forty-week season each year, eighteen to twenty different programs. Abravanel conducts most of them. All are taped for rebroadcast by independent radio stations throughout the country.

"Almost every concert in the Mormon Tabernacle, which seats 5,000, is sold out," Abravanel says proudly. "We also record in the Tabernacle." Abravanel, who is not a Mormon, says, "The church has been very generous to the orchestra and to me personally. We have the use of the Tabernacle for our concerts completely free of charge-an enormous contribution. And in twenty-eight years there has never been a single instance of the church saying ‘we want you to do this' or ‘we don't want you to do that.' " Abravanel is unhappy, however, about some of the attitudes other orchestras have about programming today. "In Berlin a few years ago," he reports, "I proposed opening a program with Weber's Oberon Overture, and they said ‘You can't do that--it's pops.' Since when is Weber only 'pops'? It is good music, beautiful music. It was good enough for Furtwangler and Hindemith!" He finds the same attitude applies to works by Gershwin and Weill. "You know, there's a lot of snobbery around music circles, and it's a pity. I think it's a great mistake to ban from regular sym phony concerts those pieces which please all kinds of audiences. It's silly.

"People go to concerts to be moved," he continues. "I think one of the big problems with music today-why there is such a gap between the creators and their audiences-is that form has be come more important than content. In an age of computerization, I believe the role of music should be away from computerization. The role of music should be to cultivate depth, which the technological brain cannot do. Music should be a counterpoint to the time in which it is created. All this talk about 'relevance' is wrong. If it were right, someone should have asked Shakespeare 'who cares about a black man in Venice, or teenage lovers in Verona, or a crazy Dane?' In very quiet times, mankind needs tragic art-and that's why Mahler was 'rediscovered' in the 1950's. But in hard times, art should be consoling." WHO, then, does Abravanel think will be the next major composer to be rediscovered? "Bruckner," he replied immediately. "No question about it. Bruckner is the next man for America because there is a crying need for spirituality in America. Mankind, the human animal, always needs something to hold on to. It can 6e religion, or patriotism, or science and progress-but there must be some thing. Right now, America doesn't have anything to hold on to. Formal religion doesn't seem to mean that much to most people anymore, which is very regrettable in my view. People also have mixed feelings on what patriotism means, or even science.

"Bruckner is spiritual in an agonized way--yet so much simpler to understand and more monolithic than Mahler. His music is mystical and full of faith. That's why I think America will grab on to him." Abravanel feels even more strongly that the potential audience for good music in America has only just begun to be tapped. "Recordings have done a lot," he says, "but our next frontier must be to give every citizen a chance to hear good music 'live.' That's why I love touring with the Utah Symphony-to all kinds of towns that most people have never heard of. The response we get is wonderful! There is something happening in America artistically, musically, that is unique. It's a great time in our history and I'm excited to be part of it!"

===========

“Abravanel is the only Mahler cycle available at budget price."

WITH three new albums from Vanguard, issued in both quadraphonic and stereo formats, Maurice Abravanel becomes the fifth conductor to complete the Gustav Mahler symphony cycle on records. Though the Utah Symphony is not the equal of Solti's Chicago Symphony, Haitink's Concertgebouw, or Bernstein's New York Philharmonic, the general level of performance Abravanel achieves is remarkably high, and for the most part the performances are enhanced by the acoustic excellence of the Mormon Tabernacle and the intelligent engineering work of the Vanguard recording staff. Moreover, Vanguard's Cardinal and Everyman stereo discs are only $3.98 each. making Abravanel's the only Mahler symphony cycle available at a budget price. (The Vanguard quadraphonic discs are $7.98 each.) Abravanel's view of Mahler is not one of impassioned neurasthenia a la Bernstein, nor does he unleash the ardor Horenstein does in his readings of No. 1 and No. 3 on Nonesuch (or, preferably, on Advent cassettes). Rather.

Abravanel's reading of the First Symphony rates high marks in terms of carefully gauged tempo relationships and textural transparency. It all seems a little cool and distant, though-a situation aggravated by the fact that the bass line and the low percussion (in the finale, chiefly) simply do not come through with enough impact relative to the rest of the music's vertical component. Direct comparison of Abravanel's First with James Levine's rather similar "cool" and transparent reading for RCA tends to confirm my impression on this point. I suspect that the longish reverberation period of the Mormon Tabernacle forced the Vanguard engineers to compromise between maximum clarity and percussive impact.

Definitely the most successful of the new Abravanel readings, in my opinion, is the Fifth Symphony, whose contrapuntal complexities become very neatly unraveled in this conductor's predominantly light-handed approach. There is some tendency toward over prominence of the trumpet line in the lamentation episode of the opening funeral march, and I would have liked a shade quieter overall dynamic in the famous Adagietto, but these are minor flaws in a reading of generally high quality that reaches a peak in the immensely difficult fugal-texture finale.

In the great opening Adagio movement from the Tenth Symphony (left unfinished by Mahler), the Abravanel reading is cool, clear, and beautifully recorded, but the cumulative effect of the whole, particularly in those climactic episodes of eerie dissonance that point the way toward Alban Berg and beyond. lacks the power and tensile strength of the 1959 Columbia recording by George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra. And, with the best will in the world, Abravanel and his players are no match for Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic in the Sixth Symphony.

Abravanel's temperament and the makeup of his orchestra simply will not accommodate the shattering urgency Bernstein brings to this symphony, the finest achievement in his Mahler symphony cycle. The Abravanel reading is a good, conscientious job--at its best in the heart-wrenchingly poignant slow movement--but no more. The emphasis on achieving clarity of texture occasionally mars the musical result, as in the first movement and the slow movement; the cowbells, which should sound disembodied as though heard floating up from distant valleys to the heights of the Austrian Alps, sound all too close at hand.

VANGUARD'S quadraphonic sound in these recordings is no match, in terms of semi-sur round effect, for the same company's remark able series of recordings done in London with Charles Mackerras and Johannes Somary.

The root of the problem probably lies in the difficulties of controlling and altering basic acoustic ambiance-a lot easier to do. apparently. in-the English locale with its shorter reverberation period, than in the almost cavernous Mormon Tabernacle. In short. I don't think the degree of quadraphonic enhancement achieved in the Abravanel recordings is worth the $4 extra per disc. Still, in stereo, these Mahler symphonies are a good buy. especially Symphony No. 5 from this group of releases and No. 8 from the earlier Cardinal series.

-David Hall

MAHLER: Symphony No. 1, in D Major. Utah Symphony Orchestra, Maurice Abravanel cond. VANGUARD VSQ 30044 $7.98, VSD 320 $3.98.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 5, in C-sharp Mi nor; Symphony No. 10, Adagio. Utah Symphony Orchestra, Maurice Abravanel cond. VANGUARD VSQ 30045/6 two discs $15.96, S-321/2 two discs $7.96.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 6, in A Minor. Utah Symphony Orchestra, Maurice Abravanel cond. VANGUARD VSQ 30047/8 two discs. $15.96, S-323/4 two discs $7.96.

================

---