EQUIPMENT TEST REPORTS by Hirsch-Houck Laboratories : Hirsch -Houck Laboratory test results on: the Dokoder 1140 four-channel tape deck; Onkyo Model 8 speaker system; Tandberg TCD-310 stereo cassette deck; Rotel RA -1412 integrated stereo amplifier; and an addendum on the Uher 134 cassette recorder test

Dokorder 1140 Four-channel Tape Deck

THE Dokorder 1140 is a deluxe, four-channel, open-reel tape deck designed for the advanced amateur recordist. Though not advertised as a "professional" recorder, it has many of the recording functions used by professional recording engineers. "Multi-Sync" is Dokorder's term for their track-synchronizing feature in which a portion of the four-channel record head is used to play back a previously recorded track so that new material can be recorded on one or more of the remaining tracks in exact synchronism.

The Dokorder 1140 operates at 7 1/2 and 15 inches per second (ips), and can accommodate reels up to 10 1/2 inches in diameter. The wood-veneer base contains the nearly horizontal, slightly sloping tape transport and its operating controls. A vertical column at the rear supports the electronic portion of the recorder, which is some 7 inches above the surface of the deck. With the recorder placed on a table or bench of normal height, the meters and controls in its electronic section are close to eye level, while the transport controls fall easily to hand.

The tape capstan is driven by a synchro nous motor whose speed is switched electrically by a pushbutton that simultaneously selects the appropriate equalization. Two six-pole motors operate the reel hubs, which have integral spring-loaded reel hold-downs. The tape moves in a nearly straight-line path, with tension arms on each side of the head assembly. The transport shuts down automatically if tape tension is lost. Five flat feather-touch pushbuttons control the tape motion through-solenoids. A control-logic system prevents tape damage or spilling, no matter how the controls are used. An optional remote-control assembly can be plugged into a socket on the front of the base.

Six pushbuttons at the left of the panel control the POWER, REEL (torque settings for 7-inch or 10 1/2-inch reels), SPEED, BIAS, cue, and PAUSE functions. In the FIX position of the BIAS switch, the bias is set by internal adjustments which are factory set for Scotch 212 or Maxell UD-35 tape. Pushing it to the VAR position makes it possible to optimize the bias for any tape by means of four small knob controls on the panel (their settings are protected by a removable plastic cover). The CUE button releases the tape lifters so that a specific portion of a recording can be located by fast search or manual tape scanning.

Along the front center of the panel are four red RECORD interlock buttons. When the main REC button is pressed, a red light next to each of the four channel-recording selectors indicates when it is engaged. Behind the massive head cover and shield are four MULTI-SYNC buttons. Pressing any one of them connects the record-head section for that channel to its playback amplifiers for synchronous addition of other program channels. The head is switched automatically between recording and playback functions by the regular operating controls.

The Dokorder 1140 has an unusual and useful MEMORY feature which is a more refined version of the "memory" devices found on some cassette recorders. It has two independent four-digit index counters whose numbers move in opposite directions as the tape moves. In use, the "forward" counter is set to zero at the beginning of a selection and the "reverse" counter is zeroed at the end of the selection. If a switch at the right of the panel is set to AUTO-STOP, the tape goes into rewind automatically when the "reverse" counter reaches zero. It rewinds until the "forward" counter returns to zero. Since some over shoot is unavoidable at high speeds, the tape stops, then moves forward at normal speed to the zero point, where it is ready to be placed into the normal playback or recording mode.

Another switch setting, REPEAT, produces the same result, except that the tape automatically resumes playing from the zero point instead of waiting for an operator command. This system permits any desired portion of a tape to be repeated automatically as many times as desired. In the OFF setting of the MEMORY switch, the recorder's operation is the conventional one.

The electronics panel of the Dokorder 1140 is dominated by four large, illuminated level meters which can be switched individually to read SOURCE or TAPE (playback) levels as modified by the playback-level controls. Each track has its own recording-level control with an adjacent peak-overload light that flashes on momentary peaks greater than +8 dB which might not register on the meters. The peak indicators function during playback as well as recording, minimizing the possibility of overdriving the amplifiers in the playback mode. Switches above the knobs select either mic or LINE inputs (the two cannot be mixed).

At the right of the electronics panel are two pairs of concentric playback-level controls for the, four channels. A pushbutton selects either two-channel or four-channel operation; in the former mode the rear channels are disabled and their meter lights turned off.

A slide switch selects either NORMAL or SPECIAL recording equalization to provide flattest overall frequency response with tapes that require similar bias levels but have different high-frequency properties. As an example, the instructions recommend using NOR MAL with Scotch 212, but SPECIAL (which has slightly less high-frequency recording boost) with Maxell UD-35. Finally, a slide switch turns on an internal "pink-noise" test-signal generator for adjusting the bias to any tape formulation. While recording this signal and monitoring the playback output on the recorder's meters, the bias controls for the individual channels are adjusted for the maximum output reading.

On the left side of the electronic unit are two stereo-headphone jacks for monitoring either front or rear channels with 8-ohm phones. On the right side are four jacks for 600-ohm dynamic microphones. In the rear are the four pairs of LINE inputs and outputs.

Because of its unusual styling and many control features, the Dokorder 1140 presents an impressive appearance. Its base is 17 inches wide by 16 inches deep, and the overall height is about 21 inches. The recorder weighs about 55 pounds. Price: $1,199.95.

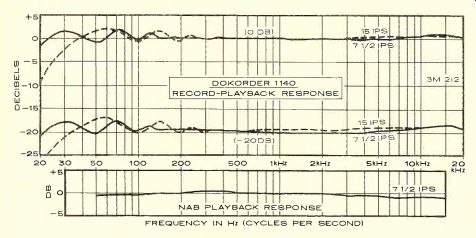

Laboratory Measurements. The playback equalization at 7 1/2 ips was extremely accurate, producing a response within ±1 dB over the 50- to 15,000-Hz range of the Ampex test tape. Most of our recording and playback measurements were made with Scotch 212 tape, for which the machine had been adjust ed. However, we also measured its frequency response with Maxell UD-35 and with TDK Audua (which required a different bias level, easily set with the aid of the Dokorder's built in test generator and the VAR bias controls).

At 71/2 ips, the record/playback frequency response showed the usual cyclic "ripples" (a function of the head design) at low frequencies. Overall, however, it was essentially within ±1.25 dB from 20 to 24,500 Hz at a-20-dB recording level, and was down 3 dB from its mid-band response at 28,000 Hz.

There was very little compression of the high frequencies at a 0-VU recording level, so the overall response was ±1.5 dB from 22 to 22,000 Hz.

--------- FREQUENCY IN Hz (CYCLES PER SECOND)

Starting from such an outstanding response at 7 1/2 ips, we could hardly expect a great improvement at 15 ips. Except for a slightly flatter response above 15,000 Hz and some loss of deep bass, the difference between the two speeds was negligible. At 15 ips the overall response was ±1.5 dB from 35 to 24,500 Hz and down 5 dB at 23 and 32,000 Hz. However, at the higher speed there was absolutely no difference between the response curves made at-20 dB and at 0 dB all the way up to our 40,000-Hz upper measurement limit! Measurements with the Maxell and TDK tapes showed that the Dokorder 1140 gave virtually identical frequency response with all three tapes. When the bias adjustment is made using the recommended procedure, and the proper recording equalization is used, this machine can produce superb results with any good-quality tape.

A LINE input of 72 millivolts (mV) or a mic input of 0.3 mV was needed for a 0-VU re cording level. The microphone inputs over loaded at 60 mV, which should be a safe value for most recording situations. The playback output depended somewhat on the type of tape used, but with Scotch 212 the maximum output was 1.8 volts from a 0-VU recording at 1,000 Hz. With the meter 'set to 0 VU by means of the playback level control, the out put was 0.79 volt.

At 7 1/2 ips, the playback distortion from a 0-VU, 1,000-Hz recording was 1.9 percent, and the 3 percent reference level was obtained at an input of +2 VU. At 15 ips, the 0-VU distortion was 1.6 percent, and a +3- VU input gave 3 percent playback distortion.

The unweighted signal-to-noise ratio (S/N), referred to the 3 percent distortion playback-output level, was 55.5 dB at 7 1/2 ips and 54.7 dB at 15 ips. With IEC "A" weighting, these figures improved to 62 and 61.5 dB, respectively. At maximum recording gain the noise level was 4.5 to 5 dB higher through the microphone inputs than through the line inputs (a relatively small increase compared with the performance of many tape recorders we have tested).

The tape transport had a combined wow and flutter (unweighted rais) of 0.085 percent at 71/2 ips when playing the Ampex 31326-01 flutter test tape. A combined record-playback flutter measurement actually gave slightly lower readings -- 0.07 percent at 71/2 ips and a very good 0.055 percent at 15 ips. The tape speed was less than 0.25 percent fast, and in the fast-forward or rewind modes a 1,800-foot tape reel was handled in 90 seconds. The meters were somewhat slower than standard VU meters, reaching 60 percent of their steady state readings on 0.3-second tone bursts (the VU standards call for 99 to 101 percent). The PEAK lights were effective in disclosing excessive recording levels, even when the meters read well below 0 VU.

Comment. At the time we tested the Dokorder 1140, only a preliminary operating-instruction manual was available, so we had to become familiar with its many features through trial and error. While we may have overlooked a few of its special operating characteristics in the process, we were soon convinced that it is at least as versatile as any four-channel recorder we have seen, and easier to operate than many, in spite of its seemingly formidable control lineup.

In view of the limited repertoire of pre recorded four-channel tapes, it is likely that most people will be using the 1140 for live re cording by "laying down" successive tracks based on an initial program track with the intention of mixing down ultimately to a stereo tape. This is the major application for tape recorders with this capability, and one which the 1140 handles in an eminently satisfactory manner.

For example, we found absolutely no measurable or audible difference in its response or other characteristics between a playback through the normal playback head and a play back using the recording head in the MULTI-SYNC mode. Since the switching from record to playback functions is handled automatically, it is very convenient to leave the MULTI-SYNC buttons depressed and the MONITOR buttons in their SOURCE positions. In this way the selection of recording or playback modes is governed entirely by the operation of the RECORD buttons and the REC master button.

If the machine is put into the recording mode with the channel recording buttons out (disengaged), and if the previously recorded material is monitored through the Multi-Sync heads, one can make a "flying start" recording when adding material to a previously re corded track or inserting new material within the earlier recording. Pressing any of the re cording buttons instantly converts that channel from playback to record status (and re turns it to playback when released) with none of the time-delay error inherent in conventional three-head recorders. We were also pleased to find that the headphone volume, even with 200-ohm phones, was very loud and would probably be sufficient for monitoring during a "live" recording session. This is in contrast to most tape recorders, which barely drive higher-impedance phones to a listenable level. The memory feature worked very smoothly. As the preliminary instruction manual warns, there is a slight error in returning to the "0000" index-counter reading, so that replay actually begins at 0002 or 0003. By making allowance for this, it is possible to repeat or return to the beginning of any desired tape segment with great precision and at considerable speed.

We found the tape-loading process to be exceptionally simple, even for someone with more than the normal quota of thumbs. All solenoid-controlled recorders emit an audible "clunk" when their control buttons are operated, and this one is no exception. In any event, none of the acoustic output of the solenoids affects the taped program. All in all, the performance, versatility, and striking physical design of the Dokorder 1140 add up to make it an outstanding value despite its not in considerable price.

Onkyo Model 8 Speaker System

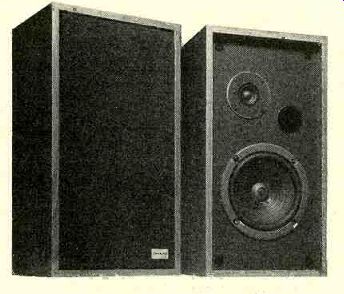

THE least expensive Onkyo speaker sys tem is the company's Model 8, a two-way bookshelf system with an 8-inch woofer and a 2-inch cone tweeter. The electrical crossover is at 6,000 Hz and a three-position switch in the rear of the speaker provides a ±2-dB adjustment of the high-frequency level about the "normal" (or nominally flat) position.

The Onkyo Model 8 is a compact speaker measuring 21.5 x 11.5 inches, with a depth of 9 3/4 inches; it weighs only 16 pounds. Its duct ed-port wooden cabinet is finished in walnut grained vinyl. A minimum amplifier power of 7 watts into its 8-ohm-rated load impedance is recommended, and the speaker is rated to handle up to 30 watts. The Onkyo Model 8 carries a five-year warranty covering parts and labor. Price: $89.95.

Laboratory Measurements. At the NORMAL setting of the high-frequency level switch, the integrated output of the speaker in the test room was unusually flat, with no significant peaks or holes up to 15,000 Hz, above which the output dropped rapidly. The close-miked bass response showed virtually no output in crease at its resonant frequency, so that splicing the two curves yielded a composite response within ±3 dB from 55 to 15,000 Hz.

The contribution of the port to the total bass output was significant only at frequencies below 50 Hz. The woofer distortion at a 1-watt drive level was under 1 percent down to about 60 Hz, rising to 5 percent at 45 Hz and to 10 percent at 38 Hz. However, distortion from the port measured considerably lower, reaching only 6.5 percent at 35 Hz.

The woofer's power-handling capacity is modest, and this was reflected in the substantial increase in distortion when we drove the speaker at a 10-watt level. The distortion was between 3 and 7 percent from 100 to about 53 Hz, and rose to 10 percent at 46 Hz.

The system impedance fell to a minimum of about 5 ohms in the 150- to 200-Hz area but averaged about 8 ohms over most of the audio frequency range. At the bass resonance of 70 Hz it rose to about 15 ohms. Although we would have expected the high-frequency level control to affect only frequencies above 6,000 Hz, its action began at about 600 Hz. It appeared to have a shelved characteristic-that is, all frequencies above 700 Hz or so were affected to the same degree, for a total range of ±2 db.

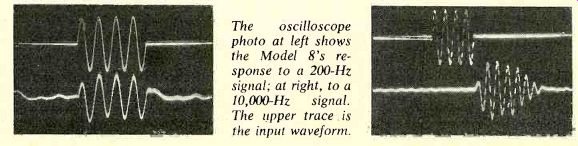

The tone-burst response at 200 Hz, in the woofer's operating range, was very good. At 10,000 Hz, the burst decayed over a period of several cycles instead of cutting off abruptly, although there was no sustained ringing. The efficiency of the Model 8 was unusually high for a speaker of its class, so that a mid-range input of 1 watt produced a sound-pressure level of 94 dB at a distance of 1 meter from the grille.

Comment. From the measurements, one would expect the Onkyo Model 8 to be a smooth and relatively uncolored-sounding speaker with rather modest low-bass performance. And that is, in fact, a fair description of its sound.

It came as a slight surprise, however, to find that it was exceptionally accurate in its handling of our simulated live-vs.-recorded listening comparison which excludes frequencies below about 200 Hz. The flatness of its measured frequency response obviously correlates well with what one hears in a normal listening environment. Its lack of "flash" or other immediately audible characteristics signifies accuracy, rather than any deficiency, in its behavior.

---------------- The oscilloscope photo at left shows the Model 8's response to a 200-Hz signal; at right, to a 10,000-Hz signal. The upper trace is the input waveform.

Onkyo's power ratings for the Model 8 are completely realistic. That is to say, it will de liver a healthy and clean output when driven by any of the lower-price receivers rated at 8 to 12 watts per channel. However, if higher power (appreciably in excess of the 30-watt maximum rating of the speaker) is available, one might wish to use a speaker with a more extended low-bass response, which has been sacrificed in the design of the Model 8 in the interests of higher efficiency. But be aware that a typical small bookshelf system is 3 to 5 dB less efficient than the Model 8, and thus re quires two to three times as much power from your receiver or amplifier to achieve the same acoustic output.

It is also worth noting that the size and weight of the Onkyo Model 8 qualify it as a true bookshelf speaker that does not require extra-deep or reinforced shelves. In every respect, it qualifies as a fine choice for use in a modestly priced-and therefore modestly powered-home music system.

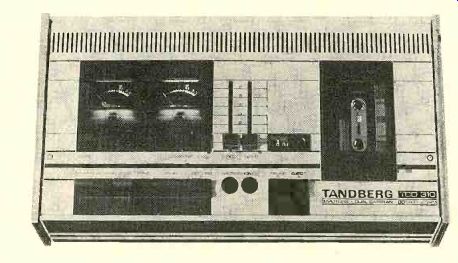

Tandberg TCD-310 Stereo Cassette Deck

TANDBERG'S TCD-310 cassette deck is an evolutionary step beyond the company's previous Model TCD-300. It is a three-motor, two-head machine with a dual-capstan drive that maintains controlled tape tension over the heads. A hysteresis-synchronous motor drives the capstans and two d.c. motors power the reel hubs. The recorder can be operated horizontally or vertically or even mounted on a wall.

The transport functions are actuated by electromechanical solenoids, but the actual operating controls resemble the latching "piano keys" used on conventional, mechanically switched transports. They can be used in any sequence without pressing the STOP key (although STOP must be pressed before a cassette can be ejected). The keys can also be left in their mechanically latched positions so that subsequent application of a.c. power by an external clock timer can initiate unattended recording or playback.

As in their open-reel machines, Tandberg has emphasized low noise in the TCD-310 through the choice of parts and circuit de signs. In particular, the microphone preamplifiers are automatically adjusted (in gain) by the impedance of the microphone(s) used to provide optimum signal-to-noise ratio (S/N).

The control keys, unlike those of most recorders, are hinged in front and must be operated by pressing on their rearmost portions. A firm pressure is required, so that it may be necessary to hold the machine with one hand while operating the keys if the vertical mounting position is used.

To make a recording, the pause key must first be pressed, and then the record key (not both record and play, as is the usual practice).

Recording levels can then be set with the two slider controls, and when the pause key is re leased the recording commences. The other transport controls are conventional, including fast speeds in both directions, PLAY (its key is twice as wide as the others), and a power switch.

An interesting additional feature of the TCD-310, not mentioned in the instruction manual, is its ability to be used as a "straight-through" decoder for FM Dolby programs.

To do this, the pause control is first engaged, then both record and play are pressed. If the tuner does not have the required 25-microsecond de-emphasis, an external adapter should be used to provide it.

The top of the Tandberg TCD-310 is conventional-appearing except that the cassette well opens to the right. This is to prevent the cassette from falling out when the door is opened with the machine in a vertical position. There is an index counter next to the cassette well, in front of which are the pause and eject keys. At the left is a large "window" area, behind which are the level meters, illuminated in red and green when the unit is on. They are peak-responding meters that monitor levels after the recording equalization, therefore minimizing the chances of distortion from excessive recording levels at high frequencies.

A row of what appear to be black pushbuttons is just below the meters. Actually, only three are functional-for mono recording, Dolby noise reduction, and chromium-dioxide (CrO2) bias and equalization. Between the meters, a large rectangle is illuminated in red when the machine is in the recording mode.

Two microphone jacks on the panel automatically disconnect the line inputs when the plugs are inserted. The line inputs and out puts, including a DIN socket, are in the rear of the deck.

The Tandberg TCD-310 measures 16 7/8 inches wide, 4 1/2 inches high, and 9 inches deep; it weighs 14 1/2 pounds. It is supplied with walnut side panels. Price: $499.50.

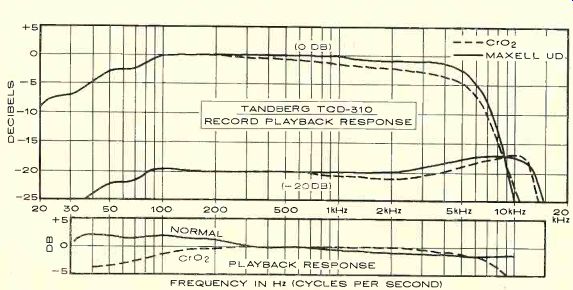

Laboratory Measurements. The TCD-310's playback frequency response varied less than ±2 dB from 31.5 to 10,000 Hz with the Nortronics AT 200 test tape ("standard" equalization). With the Cr02 button depressed, the chromium-dioxide equalization test tape gave a response within +0,-4 dB from 40 to 8,500 Hz, dropping 6 dB at 10,000 Hz.

The recorder was biased for Maxell UD tape, with which the record-playback frequency response was ±2.5 dB from 45 to 14,000 Hz at a-20-dB recording level. With TDK KR (CrO2) tape, the response was ±2.5 dB from 50 to 13,500 Hz at the same level.

For a 0-VU recording level, response was down 4 to 5 dB at 6,000 Hz. Dolby tracking was good, with less than 1 dB of change in the response at any frequency when the Dolby system was used.

------- FREQUENCY IN Hz (CYCLES PER SECOND)

At maximum gain the line inputs required 30 millivolts (mV) for a 0-VU recording level.

The recording amplifiers overloaded at a very safe 4.4-volt input. Since the microphone sensitivity is a function of the source impedance, we can only say that with a 600-ohm source a mere 80 microvolts (0.08 mV) was needed for a 0-VU recording level, with overload occur ring at a 16-mV input. However, by experimenting with different source impedances, we determined that if the recording-level controls were set at least one-half division (out of a total of six) above their minimum positions, the microphone circuits were not overloaded by any signal that did not drive the meters above 0 VU. The playback output, which was at a fixed level, was 0.78 volt from a 0-VU input.

A Dolby calibration-level tape gave a meter indication of-1 VU on playback (0 VU is the nominal Dolby calibration point, and a 1-dB error is well within normal tolerances). When a 1,000-Hz signal was recorded at 0 VU, the playback total harmonic distortion (THD) was 1.5 percent with Maxell UD and 1.6 percent with TDK KR tape. The reference distortion level of 3 percent was reached at about +3 VU with both tapes, at which level the un weighted signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) was 52 dB with Maxell UD and 54 dB with TDK KR.

Applying IEC "A" weighting, which gives a better correlation with audibility, improved these measurements to 59 and 62 dB, respectively. Finally, when we used the Dolby sys tem we obtained the most impressive S/N measurements of 66.5 dB with Maxell UD and 68 dB with TDK KR tape. Although the noise increased through the microphone inputs (the amount depending on the source impedance), the added noise at any usable setting of the level controls was insignificant.

The tape speed was nearly exact (about 0.2 percent fast), and the flutter and wow were among the lowest we have ever measured on a cassette recorder-respectively, 0.08 and 0.01 percent (unweighted rms). Another advantage of the three-motor transport was its extraordinarily fast shuttling speeds, which moved a C-60 cassette from one end to the other in less than 34 seconds! The peak-reading meters read 100 percent of their steady state levels with the 0.3-second tone burst used to check VU meter ballistics. Even when we applied 50-millisecond bursts at a rate of once per second, the meters read only 2 dB under their steady-state levels.

Comment. We have two quibbles with the human-engineering aspects of the TCD-310, the first of which concerns the buttons located just below the meters. It is by no means easy to tell when the CrO2. Dolby, and mono but tons are engaged except by feeling or closely examining them. Secondly, we are concerned about the limited clearance on the right side, where the cassette is loaded and removed. If the recorder is placed against a wall or another component, loading and unloading a cassette becomes an awkward process.

Our overall test results dramatically show the effect of Tandberg's design philosophy, which is to drive the tape with the lowest possible flutter and to keep noise and distortion at a minimum. In both respects, the TCD-310 is one of the outstanding machines in a market well populated with fine cassette recorders.

----- The TCD-3 His tape-well cover holds a cassette in integral

slots. The clear top plate of the cover snaps off to permit easy head

access.

To achieve the outstanding performance of the TCD-310, a "trade-off" was required in the response at the highest audible frequencies. Although no apologies need be made for a 14,000-Hz response, it is well known that some other cassette recorders have a useful response extending above the 15,000-Hz region. In my view, the validity of Tandberg's choice is illustrated by the fact that, while few people will miss-or even be able to detect the absence of-the frequencies above 15,000 Hz, anyone can hear noise, and most tape re cording enthusiasts will agree that there is no such thing as too little flutter!

All in all, we must say that the Tandberg TCD-310 is a superb performer-a cassette recorder whose dynamic range and flutter compare very favorably with some first-rate open-reel machines and are distinctly superior to those of most cassette recorders.

Rotel RA-1412 Integrated Stereo Amplifier

OVER the years, the Rotel components we have tested-usually in the low- to medium-price range-have more than lived up to the claims made for them. Rotel has now entered the higher-price component market with the introduction of their Model RA-1412 integrated stereo amplifier. The RA-1412 is rated to deliver 110 watts per channel into 8-ohm loads, from 20 to 20,000 Hz, with less than 0.1 percent total harmonic distortion (THD). It has just about every control feature found in other deluxe integrated amplifiers, plus a few of its own.

The Rotel RA-1412 is physically rather large, with front-panel dimensions of 21 1/4 by 7 inches and an overall depth of 17 inches.

The amplifier's net weight of more than 48 pounds results partially from its having two entirely separate power supplies that share nothing but the line cord and the power switch. This is a costly-but effective-way of guaranteeing that each channel will operate completely independently of the other.

The front panel, which is fitted with rugged handles, is dominated visually by a secondary panel, across its upper censer, which contains two large illuminated meters and the con centric volume and balance controls. The meters have extended logarithmic scales calibrated directly in power output over the very wide range of 0.01 to 200 watts. The volume control works in twenty-two detented steps, controlling the level in 2-dB increments down to-30 dB and in progressively larger jumps to -60 dB, with the final step being the fully off position. The balance control is a shallow ring surrounding the volume control, lightly detented at its center position.

At the upper left of the panel are the push button power switch and three pushbuttons for energizing up to three sets of speakers in any combination. There are two stereo-head phone jacks below the speaker switches. The upper right of the panel is devoted to the five pushbutton input selectors (for two magnetic phono cartridges and three high-level inputs).

Below them is a microphone jack and its mixing level-control knob, which is pulled out to turn on the microphone circuits.

The other controls, forming a line across the lower portion of the panel, include the bass and treble tone controls (eleven-position rotary switches), between which are a pair of ...

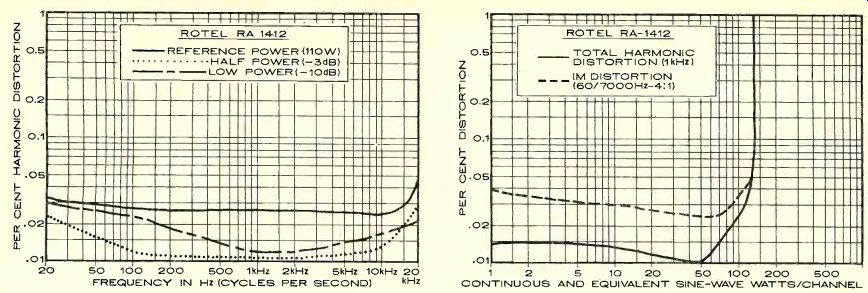

-------- FREQUENCY IN Hz (CYCLES PER SECOND CONTINUOUS AND EQUIVALENT SINE-WAVE WATTS/CHANNEL

...three-position lever switches that bypass the tone controls or select turnover frequencies of 200 or 400 Hz for the bass, 2,500 or 5,000 Hz for the treble. Two more switches operate the low- and high-cut filters, which have 12-dB-per-octave slopes and turnover frequencies of 15 or 30 Hz for the bass and 8,000 or 12,000 Hz for the treble. The MODE switch selects normal or reversed-channel stereo and feeds either left or right channel or their sum (mono) to both speakers.

Two lever switches perform functions that are found on many amplifiers, but in a manner unique to the RA-1412. The loudness-compensation switch provides two different response characteristics, identified somewhat cryptically on the panel as 6 dB/20 dB and 3 dB/10 dB. The specifications make it clear that these numbers refer to the maximum boost at 10,000 and 50 Hz, respectively, at the lowest settings of the volume control. The MUTING switch introduces either 10 or 20 dB of attenuation, either as a temporary volume reduction or (in conjunction with the volume-control and loudness-compensation circuits) to provide almost any desired amount of bass and treble boost at low listening levels.

The last front-panel control is the TAPE MONITOR switch, whose five positions permit listening to the source or the playback with either of two tape decks or dubbing from either machine to the other.

All signal inputs and outputs (except for speakers) are located on the right side panel of the RA-1412. The connections for the two tape recorders are duplicated by DIN sockets.

Slide switches under the phono inputs provide a choice of three different cartridge load resistances (25, 50, or 100 kilohms) and input sensitivities of 2, 4, or 8 millivolts. There are separate preamplifier-output/power-amplifier-input jacks normally connected internally by an adjacent slide switch.

On the left side panel of the amplifier are heavy-duty binding posts for three pairs of speakers. The rear of the unit is devoted al most entirely to the output transistors and their heat sinks, below which are the line fuse and four switched a.c. outlets. There are no user-accessible speaker fuses, since the RA-1412 has an effective electronic protection system that shuts it down instantly in the event of an overload or short circuit that might damage the amplifier. When it shuts down, a red light comes on between the meters. To restore normal operation, the amplifier must be switched off for a moment and turned on again. The protective relay also provides about 15 seconds delay every time the amplifier is turned on, preventing any transients from reaching the speakers. Price: $749.95.

Laboratory Measurements. Following the one-hour FTC preconditioning period and five minutes of full-power operation (which the amplifier easily took in its stride), we measured the clipping power output with a 1,000-Hz test signal. Into 8 ohms, it was 128 watts per channel; it increased to 182 watts into 4 ohms (the protective circuits were tripped at that level), and decreased to 81 watts into 16 ohms.

The THD at 1,000 Hz was about 0.015 percent at almost any listenable power level, reaching 0.03 percent only at the rated power output. It was still less than 0.05 percent just before clipping occurred at about 130 watts.

Intermodulation distortion (IM) was between 0.025 and 0.05 percent from about 20 milliwatts (mW) to 130 watts, and it rose only to 0.13 percent at about 3.5 mW output. This at tests to the lack of crossover-notch distortion in the output of the RA-I412 (the distortion products were principally second and third harmonics).

At the rated output, the THD was virtually constant across the audio-frequency range between 0.025 and 0.033 percent from 20 to 15,000 Hz, with a maximum of 0.045 percent at 20,000 Hz. At outputs of-3 and-10 dB, the distortion was always less than at full power.

A high-level input of only 40 mV was need ed to drive the amplifier to a reference output of 10 watts, and the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) was an excellent 80 dB. At the three rated phono sensitivities of 2, 4, and 8 mV, inputs of 0.6, 1.1, and 2.2 mV drove the amplifier to 10 watts with an equally impressive 75.5-dB S/N. The phono-overload capabilities of the RA-1412 broke all records for amplifiers we have tested; depending on the input sensitivity, the circuits overloaded at 310, 580, or 1,150 mV. The microphone input sensitivity was 0.54 mV with a 72-dB S/N, but it was able to accept the full 10-volt output of our audio generator without clipping! The bass tone controls had a variable turn over frequency (at or below the value indicated on the panel), and the treble controls were "hinged" at approximately the indicated frequencies. For the listener who knows what he wants to hear, these tone controls should be able to provide almost any desired frequency-response characteristic. The filters, as rated, had desirable 12-dB-per-octave slopes. The-3-dB frequencies of the high filter were 6,300 and 9,500 Hz, and for the low filters they were at 20 and 35 Hz. Either of the latter should do an effective job of turntable-rumble reduction with absolutely no effect on audible program content.

The loudness contours have been chosen so that they do not begin to take effect until the volume control is set below its-20-dB position (about mid-way in its range). However, the bass boost was very mild until the volume setting reached-37 dB, below which it be came rather drastic. As indicated by the specifications, the 3 dB/10 dB setting of the switch gave about half as much boost as the 6 dB/20 dB setting. However, choosing between the two seems almost unnecessary in view of the 10- and 20-dB attenuator settings, which should permit the volume control to be set for almost any desired degree of loudness compensation at the chosen listening level. The high-frequency boost of the loudness circuit was hardly measurable except at the lowest volume settings.

The RIAA phono equalization was accurate within ±0.5 dB from 100 to 20,000 Hz, with a slight bass rise to a maximum of +3 dB at 35 Hz. It was essentially unaffected by cartridge inductance, so that the response varied less than 0.5 dB up to 20,000 Hz when we drove the phono inputs through the coils of several popular cartridges.

Comment. The performance of the Rotel RA-1412 speaks for itself. In our tests, it easily surpassed its significant published specifications. By the most critical standards this amplifier is superb, and in today's market it is priced quite competitively. (In other words, we doubt that a better amplifier, with similar power and control features, can be bought for less money.) The power-output meters are a useful fea ture, if only for educational purposes. Many people will find it difficult to believe that their average listening is done at levels of a few milliwatts, and yet peaks can drive the meters to many tens of watts. The meter indications on our sample were somewhat optimistic, reading from 20 to 50 percent higher than the true power into 8-ohm loads (which we assume they were calibrated for). In fact, much of the time their readings were close to correct for a 4-ohm load.

Some of the most attractive aspects of the RA-1412 do not lie in the area of specifications or electrical performance. Once an amplifier has been refined to the point reached in this one (as well as some others of comparable quality), the human-engineering factors become more important in making distinctions between competitive products.

The "feel" of the controls and switches of the Rotel RA-1412 almost defies description.

Every control has a combination of smooth ness, lightness, and positive detenting that is better experienced than described. One of the most impressive things we did with the RA-1412 was to switch between its inputs with all gain controls at maximum and the speakers connected. Needless to say, the high-level program sources were turned off (but still connected) for this test. Most amplifiers-even expensive ones-will give some indication of a switching transient (seldom severe enough to blow out a speaker, but at least audible) when operated in this manner.

The Rotel RA-1412 was totally silent. Whether this has been achieved by special shorting switch contacts or by good electrical design we do not know. The point is that this amplifier not only does everything it is supposed to do, but at the same time it does nothing that it is not supposed to do. The latter consideration is often overlooked, but it is to us an indication of a truly excellent and well-thought out design.

Addendum: Uher 134 Cassette Recorder

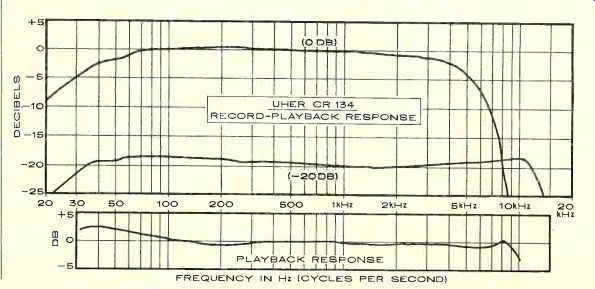

WHEN we tested the Uher CR 134 cassette recorder (STEREO REVIEW, November 1975) we noted a frequency-response characteristic that suggested incorrect biasing for the tape we used ( TDK SD). Uher informed us recently that the recorder was biased for Maxell UD. A second unit was submitted for test, and we measured its record-playback frequency response with Maxell UD. The result was quite different from what it was with our first sample: a rising high-frequency response instead of the original droop, and an overall response of ±2.5 dB from 33 to 13,500 Hz.

We repeated the measurement with TDK SD tape, which had shown a loss of highs on the first machine we tested. The new machine gave an outstandingly fine response with TDK SD-nearly flat over the full range and within ±1.5 dB from 29 to 13,000 Hz. It appears therefore that most high-quality ferric-oxide tapes will provide satisfactory performance.

A playback-response measurement yielded a curve very similar to that of the first unit, with slightly flatter overall response. Other characteristics, such as flutter, were essentially identical in both samples tested. Our conclusion is that the Uher CR 134 is indeed an excellent machine, fully on a par with many home cassette decks in all its essential characteristics. In addition, it has the special virtues of compactness and battery operation.

------------- FREQUENCY IN Hz (CYCLES PER SECOND)

------------

Also see:

TECHNICAL TALK, JULIAN D. HIRSCH