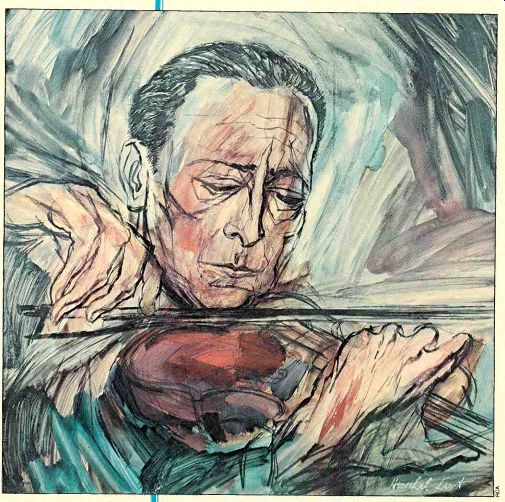

A diamond-jubilee testimonial

by Irving Kolodin

WELL over fifty years ago, when the Twenties were just beginning to roar, two talented brothers in search of material with which to entertain party-giving friends hit on the idea of a patter song called Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, Sascha. It wasn't by any means the best song the Gershwins ever wrote, but it was one in which Ira was able to make a small lyrical mark by rhyming "Auer" with "sour"--to wit:

When we began,

Our notes were sour

Until a man

(Professor Auer)

Set out to show us, one and all,

How we could pack them in, in Carnegie Hall.

Pride of place, it may be noted, was assigned to Mischa. This was a proper concession to seniority, but Mischa (Elman) rarely rated ahead of Jascha (Heifetz) again. Indeed, even in 1921 (when the song was written), priority, if not seniority, had already gravitated to Heifetz.

Of the celebrities grouped in the Gershwins' foursome, Jascha alone still endures (as fortunately, too, does the man who put the words together), an undefeated champion.

Were there such a thing as a Davis Cup for international eminence in the execution of down-bows, spic catos, fingered octaves, and staccatos, Jascha Heifetz would long since have retired enough cups to put a dent in the world's silver sup ply. But he has, in other ways and in sundry manners now almost forgot ten, amassed enough credentials as a public figure, as a citizen with a solid social consciousness, and as a musician of one-world/one-word identity to make an award to him for his outstanding contributions to the quality of American musical life (on the seventy-fifth anniversary of his birth in Vilna, Russia, on February 2, 1901) not merely merited but overdue.

No Gallup, Harris, or other poll has ever been conducted on the subject, but insofar as I can discover by offhand count, there are only two ways in which Heifetz is faulted by a generation of critics unborn when he was already famous: (1) he doesn't play in public as often as he should, and (2) he has been known at times to play not wisely but too well (in terms of the material on which he has lavished his art). To the first objection a question may be opposed: How many violinists who began concertizing at seven were (are) still at it fifty years later? As for the second objection, it was Othello who asked that he be re membered as "one who loved not wisely but too well"; if Heifetz's lifelong love affair with the instrument for which (and by which) he has been living since the age of three induces censure in Shakespearian terms, it is, as putdowns go, censure on a very high level indeed.

In the aggregate, and despite all such quibbles, the identity of Heifetz as a paragon, a nonpareil, a monarch of the violinistic realm is so long and so widely established that it is cited as a standard even by those who have very likely never heard him perform, least of all in person. In the reportage of last fall's World Series, a columnist for the New York Times was searching for an image with which to illustrate the indignity implied in expecting high priced baseball talents to perform at their best at night in Boston's usually blustery late-October weather.

Expostulated Dave Anderson: "Nureyev isn't asked to dance on ice, Heifetz never had to play the violin with mittens." Nicely put. But what are the chances of Nureyev's being cited as a standard of comparison sixty years after his New York de but? That would be somewhere in the year 2025, by which time (assuming that all reliable precedents remain intact) one, two, or three other top terpsichoreans-Lett, or Lapp, or whatever-are likely to have surpassed Nureyev's accomplishments and displaced him as a standard. That has not yet happened to Heifetz, whose command of his instrument may well remain unchallenged for another eon or two, whose name even then will remain a permanent, seven-letter synonym for violinist.

IF one is to have any real comprehension of what the Heifetz career has meant to American music, one has to talk in terms not of years but of decades. Ideally, I suppose, one should remember it all, one should have pursued a parallel course, year by year, decade by decade. In one way or another-student, admirer, critic--I have had (with the exception of the first half-dozen of those years) that order of experience, and I would rate the course that Heifetz has run as a tireless, matchless marathon. Without making any special point of it, or firing a Parthian shaft from his bow in anger, Heifetz has faced down every challenge to his supremacy. He has always had in reserve some special distinction such as playing the Bach Chaconne better at seventy than he did at seventeen-some singularity that is lacking even in so surpassing a symbol of violinistic excellence as the late David Oistrakh. The other older-generation figures-Stern, Mil stein, Menuhin, Francescatti, Grumiaux, Szeryng-are great violinists all, as without question are the younger ones-Perlman, Zukerman, Zukofsky, Spivakov. But a Heifetz? The question implies its own answer.

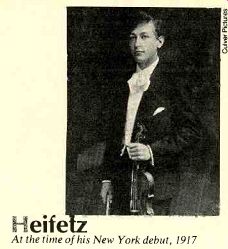

--- At the time of his New York debut, 1917

Those who didn't know the Heifetz of the Twenties and Thirties, the living, corporeal, concertizing being (and rarely have two adjacent decades so aptly summarized the distinction between a feast and a famine) simply don't know Heifetz. He soared into the Twenties on the thrust of a success whose power and range have scarcely been matched on the American musical scene in a hundred years except by Paderewski, Caruso, Horowitz, Flagstad, Callas, and Van Cliburn. Heifetz had every thing-and the word is every thing going for him, not merely matchless talent, good looks, ease, and grace in doing the impossible impossibly well, but even a priceless anecdote which summed it all up in an unforgettable one-liner.

Was it hatched in a press agent's mind? Was it apocryphal? Or was it merely an excellent instance of that classic definition of repartee: "What you think of on the way home?" Impelled by curiosity, and determined to run the story to its source, I researched the matter painstakingly through the archives and discovered that it was, unbelievably, exactly what it had always been professed to be: an apt rejoinder, on the spur of the moment, by a wit in full possession of his faculties. It was addressed to a suffering colleague who was more than a little perturbed by the storm of applause that swept through Carnegie Hall after the first piece (Vitalli's Ciacona) performed in public on American soil by Jascha Heifetz.

The suffering colleague was (almost by predestination) Mischa Elman; the wit in full possession of his faculties was pianist Leopold Godowsky. Both had given Carnegie Hall recitals during the preceding week. They were seated in a box, drawn by curiosity (as were many others) to the first appearance of a youth whose name had already be come familiar from accounts, in both the musical and general press, of his great success in Berlin.

Neither of the parties concerned has endured to give sworn, authenticated testimony of who said what to whom, but the issue of the New York Herald (later merged with the New York Tribune) in which the Heifetz debut was covered has. Reproduced herewith (probably for the first time since the historic event) are the exact words with which the Herald of the Sunday following the Saturday afternoon concert of October 27, 1917, headlined the event:

ANOTHER GREAT VIOLINIST COMES OUT OF RUSSIA

Jascha Heifetz Younger Than Messrs.

Elman and Zimbalist and as Individual as Either

After three preliminary paragraphs of praise and appraisal, the anonymous writer (more likely than not staff member Paul Morris) commented:

Big sweeping things are not as yet in Mr. Heifetz's line. He is an interpreter of refined emotions, a technician of high attainments.

His harmonics for the most part were superb, his double stopping was admirable and his tone full of vitality and beauty. He is a player that should interest American audiences everywhere.

Many leading musicians were in the audience. Mischa Elman sat in a box with Leopold Godowsky. After the first number and the audience had responded with great applause, Mr. Elman turned to his companion.

"It's rather warm," he said, wiping his fore head.

"For violinists, perhaps," Mr. Godowsky answered, "but not for pianists." That same issue of the Herald also furnished the weather for the day:

there was a low of 55 degrees at 3 a.m., a high of 64 degrees at 2:30 p.m. though inside temperatures, including that of Carnegie Hall, might be expect ed to have been a little higher! HEIFETZ, for all that he was born in Russia, had conquered the New World before he did the Old (though he made his debut as a child in Berlin). He left Petrograd with his parents just as the first shots of the Russian revolution were being fired, traveling east by way of Siberia and Japan and on to San Francisco and New York. Western Europe and Heifetz thus discovered each other the wrong way around, so to speak: the six thousand people who crowded Royal Albert Hall for his Lon don debut in 1920 knew he was Russian, but they also knew that he came from "the States." It was the same with audiences in Paris, Brussels, and

------------

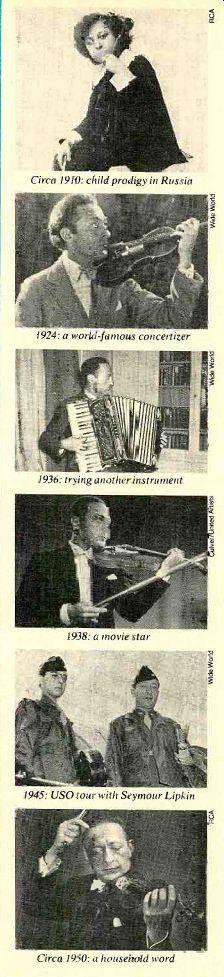

Circa 1910: child prodigy in Russia

1924: a world-famous concertizer

1936: trying another instrument

1938: a movie star

1945: USO tour with Seymour Lipkin

Circa 1950: a household word

---------------

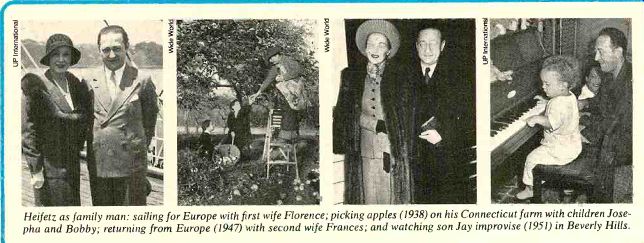

Heifetz as family man: sailing for Europe with first wife Florence; picking apples (1938) on his Connecticut farm with children Josepha and Bobby; returning from Europe (1947) with second wife Frances; and watching son Jay improvise (1951) in Beverly Hills.

-----------------

... wherever else he went. From the first appearance on he was to remain identified with America. He never craved a Swiss chalet, a French chateau, or a castle in Spain. He went, constantly, repeatedly, to Australia (1921), to the Orient (1923), to Palestine (1926), and around the world (the first of four times in 1927). But always he came back home, after 1925 as a naturalized U.S. citizen.

"Home" was, for a long time, New York's Manhattan, first an apartment on Central Park West (shared with his parents). He was easily at home among the pre-Beautiful People of the time, the Upper Crust, the Smart Set, the dudes, dolls, and dandies, spending a as family man: sailing for Europe pha and Bobby; returning from Europe (1 summer or two at socially suitable Nar ragansett Pier in Rhode Island, just a sail across the bay from Newport and Bailey's Beach. Life and the surround ings in which it was lived took a different turn when, in August of 1928, he married Florence Vidor, a beauty as well as a queen of the silent screen. She had divorced her first husband, the celebrated director King Vidor, three years before. For a time, the Heifetzes' new home was a penthouse on top of a

Fifty-seventh Street apartment house within hailing distance of Carnegie Hall.

The living was easy not only in summer but in winter time: Heifetz could be booked anywhere, his fees were excellent, and taxes hardly a hindrance to putting it all together.

The Thirties began with Heifetz twenty-nine. The Depression was on, but he could still tour. He went to Mexico, where he was photographed with an admirer he admired right back: Die go Rivera. He returned to Russia for the first time in 1934, had a hysterical success as a "visitor" from America, and remet his old (pre-Auer) teacher Professor Johannes Nalpandian, who stood in the wings and wept as he heard Wilhelmj's arrangement of Schubert's Ave Maria played more beautifully than he dreamed anyone could play it, least of all a pupil of his own.

Back in the States, there was work and play. Heifetz could draw 12,000 in the "old" ( Eighth Avenue) Madison Square Garden to benefit musicians made jobless by hard times; that was work, considering the quality of the public-address systems of the time. He could play for as many as Carnegie Hall could hold, as often as was prudent-a recital or two early in the sea son, orchestral appearances later. One of the latter, in a rather special way, marks the decade as Heifetz's own. Of all possible soloists, it was Heifetz who stood in the middle of the New York Philharmonic when Arturo Toscanini made his "farewell" appearance as the orchestra's music director on April 29, 1936. Like his greatest colleagues, Heifetz always rose to an Occasion: as soloist in the Beethoven Concerto on that surpassing occasion he was at his surpassing best.

BENEFITS were almost weekly events in those days; Heifetz was enormously responsive. Most of them, like the one noted above in the Garden, were massively public. A more intimate one took place on January 31, 1936, in his own home (again a penthouse, this one atop a famous old structure at 247 Park Avenue). It was spacious enough to accommodate an exclusive four hundred guests who paid $250 each for an evening of music by the host, Lawrence Tibbett, and Jose Iturbi. The money went into a fund for "destitute German professionals" (meaning victims of Nazi terror).

In addition to this evening at home and the one in Carnegie Hall with Toscanini, 1936 was also memorable for an April day (the 18th) on which, along with Tibbett, Alma Gluck, Richard Bonelli, Gladys Swarthout, Frank La Forge, and Deems Taylor, Heifetz at tended the first annual meeting (at New York's Plaza Hotel) of a new organization called the American Guild of Musical Artists. Tibbett was its president, Heifetz its first vice president. The stated purposes of the organization were "to promote and foster good will between the musical performers them selves and the other organized groups of the musical world, and to establish a mutual understanding and friendly relations between the artists of this country and other nations." Founded by seven men (of whom Heifetz is the only living founding officer), AGMA was modeled on Actors' Equity in that it was organized by men and women who didn't need its protective shield on behalf of other professionals who did. Its original total membership was 113, almost all of them solo performers.

When these solo performers banded together to give a benefit in those Depression times (in Carnegie Hall on February 27, 1937), it was something to remember. Sharing the backstage areas and, in relays, the stage were, among others, Josef Hofmann, Jose Iturbi, Kirsten Flagstad, Lotte Lehmann, Lily Pons, Gladys Swarthout, Lawrence Tibbett, and Lauritz Melchior. What brought them together was a desperate need for relief funds for the victims of floods in the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. Benefits, of course, come and go, but who could forget an evening in which Melchior and Tibbett joined in the great duet from Verdi's Otello (an opera the legendary Wagnerian tenor was never permitted to perform in New York), one in which Heifetz, who was appearing that same Saturday night with the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Academy of Music, joined Efrem Zimbalist in a performance of the Bach Double Concerto-via a telephone line to Carnegie Hall? Forty years after its founding, ...

--- Heifetz At the time of his television debut, 1971

...AGMA is, next to the AFM, the most influential organization of musicians in the fifty states. It now takes in not only hundreds of instrumentalists, but choristers, comprimarios, other salaried members of the nation's opera companies, and ballet dancers as well. It has remembered its original first vice president on several later occasions, including the twentieth anniversary year of 1956, by re-electing him to office.

The later Thirties witnessed the brief appearance of Heifetz in a role not so widely known as that of violin virtuoso. He had acquired a farmhouse and attached studio/barn in Westport, Connecticut, as a suburban retreat for his wife and children Josepha and Robert. When a benefit appearance by Heifetz was announced at the nearby Nor walk High School, the New York Herald-Tribune sent a reporter to find out what it was all about. It was, he discovered, to provide funds to fight a propos al to dam the Saugatuck River at the little village of Valley Forge. To his visitor Heifetz explained: "This controversy is not of personal interest to me; none of my land will be flooded or injured. But with many other residents it may be otherwise. I volunteered my services because I love America, which is one of the few remaining countries where a man can own his own land and not be disturbed." Love for America and its institutions took another turn in 1940 when, in con junction with the Cultural Division of the Department of State, Heifetz spent six months in South America, performing in all sixty recitals. At about this time he also appeared in a film for the first time, playing the congenial role of Jascha Heifetz. He then decided to make California home for his wife and growing children, in a house with a mu sic room big enough to serve as a studio (the one in which the famous trios with Rubinstein and Feuermann were re corded in 1941).

When war came, he soon decided that playing benefits and raising money through War Bond sales was not enough. He acquired a USO uniform and marching orders that took him to almost as many fronts as there were GI's. On at least one occasion the assembled troops gave little evidence of knowing who the visitor was or of caring much for what he did. Indeed, as I have heard it, Heifetz was booed. It was perhaps in response to such an experience that he decided to lighten his repertoire to include transcriptions (of his own devising) of melodies from Gershwin's Porgy and Bess. They were subsequently issued on Decca discs in 1946 (RCA was still immobilized by the musicians' union ban on recordings), along with other sides that included Irving Berlin's White Christmas per formed with an orchestra directed by T. Camarata.

Less demonstrably a matter of cause and effect is Heifetz's affection for the lighter, slighter, and even triter (because it is of greater length) material he sponsored "live" and on discs in the Thirties, Forties, and Fifties. Is it an example of Bad Taste? Can a man with a profound, lifelong affection for the music of the three big B's be given a failing grade in musical judgment? Is it laziness in learning new literature? Name a worthwhile violin work of the eighteenth or nineteenth century (ex cepting Paganini's concertos, which didn't seem to rate in the "book" of the Auer school) that Heifetz didn't play and the charge may wash. And too, we must remember that he played and recorded twentieth-century works' by Sibelius, Prokofiev, Elgar, Bloch, and Walton as well. Was it then per haps lack of enterprise? Hardly a just complaint about a man who has preferred Faure's A Major Sonata to Franck's on numerous occasions, who has given life to Spohr's Concerto No. 8 ("Gesangsszene") and Double Quartet, legitimacy to the E-flat Sonata of Richard Strauss (four recordings-and a whack on the hand from a pipe-wielding Israeli for playing it in Tel Aviv in 1953), and luster to the Scottish Fantasy of Max Bruch, a work all but forgot ten prior to the 1947 recording by Heifetz. (It has recently begotten a tribute in kind from the fastidious Arthur Grumiaux-the most Heifetz-like performance not by Heifetz of anything I have ever heard.) Then why not the sonatas/concertos of Bartok, Schoenberg, Sessions, Berg, Hindemith (save for a single, un repeated venture in 1936), Stravinsky, Szymanowski, Britten, Barber, Shostakovich? And why, oh why, in their places, the works of Gruenberg, Korngold, Rozsa, and Castelnuovo-Tedes co, all of which (plus the Walton concerto) Heifetz either commissioned or sponsored? Some exclusions and preferences (Cons for Britten, Walton for Stravinsky) may be charged to temperamental bias, a liberty to which any artist is entitled. But much more, I am inclined to think, can be attributed to a bias on behalf of the instrument with which he has had a lifelong love affair.

Some great instrumentalists-Isaac Stern is one-can pocket the musical sound for which they have paid so high a price in effort and sponsor the totally different qualities demanded by the works of Bartok, of Hindemith, of Stravinsky. Heifetz doesn't see it-or hear it-that way. The closest instance, perhaps, came in his playing and re cording of a sonata by the British com poser Howard Ferguson.

Clearly, to be acceptable to Heifetz, a work must (as a precondition to other virtues and merits) treat his instrument as he prefers to have it treated. It is not an unreasonable demand, for it is shared by many other interpreters who have spent years learning how to treat their instruments with respect. How much Dallapiccola, Nono, and Berio did Renata Tebaldi sing? Which is Maria Callas' preferred Schoenberg piece-Pierrot Lunaire or Erwartung? The answer, of course, is neither: she didn't even sing Wagner in German.

Does this put Heifetz in the prima donna category? Perhaps. But it also puts him in the category of knowing what suits his art and what doesn't.

AFTER his first marriage ended in divorce, Heifetz remarried, became a father again (another son, named Joseph and known as Jay), and tended to tour less. When (after a million and .a half miles of travel, 100,000 of them by plane, and 70,000 hours of practice and public performance, which translates into eight years, twenty-four hours a day) he decided that the life of the touring virtuoso had lost its charm, Heifetz did not exchange it for idleness. As one discipline was phased out, another re placed it: conveying to others what he had learned in fifty years of application. In a decade and a half of his professorship at the University of Southern California (or under other auspices in the Los Angeles area) he has given his time and thought to more than a hundred and fifty artist-pupils from Far East and Near, from Europe and Asia, Israel, North and. South America, the world.

Attention to his classes occupies him a full day twice a week (Tuesday and Friday). Monday and Thursday he spends answering correspondence, keeping up with paper work, records, etc. Wednesday is the housekeeper's day off, but the yardman's day on, and the grounds (Heifetz participating) have to be kept up. Weekends are for the beach house and the water (the house is just across the channel from Catalina Island). The violinists he has worked with include Erik Friedman, Elisabeth Matesky, Beverly Somach, and, perhaps most notably, young Eugene Fodor-very good violinists all, with perhaps a great one in the making.

But the results hardly serve to categorize Heifetz as another Auer or Galamian. He has sometimes, on the occasion of one of his increasingly infrequent interviews, complained of "not being able to get all those I would like to work with ... they [the teachers and the schools] don't send me their best talents, even for a short period." Some schools regard the Heifetz approach as out-and-out raids: the schools, he says with a touch of arrogance, should "send me their best" (something no school relishes).

THE present leisurely life of this once peripatetic virtuoso is a perpetual puzzler for those who expect him to act out their own fantasies: going about, seeking the applauding multitudes, earning new laurels from the younger generation of concert goers as long as life permits. Artur Rubinstein suits these expectations exactly; Heifetz frustrates them. What's the matter, the queries go, can't he cut it any more? If Casals could, why not Heifetz? Actually, Heifetz's life at seventy five is the most distinctively American thing about him. He is fulfilling the American dream of exercising his in alienable right to do, at seventy-five, exactly what he wants to do. His days are planned, the nights are for friends, for dining in or out, most often as a prelude to a program of chamber music.

On the other side of those millions of miles and thousands of hours was a rigorous routine that began at three, and Heifetz has not forgotten. On a social occasion some years ago during which celebrities were rehashing the early ages at which they began to be self-sup porting (nine, eleven, fourteen) Heifetz put in: "I started to make a living at seven"-at which Groucho Marx was heard to comment, "I suppose that be fore that you were just a bum." It might be laboring the truth to pro claim that Heifetz is a model of any thing. But he is a better example of most things that make a good American, I think, than many others, politicians and musicians included.

-------------

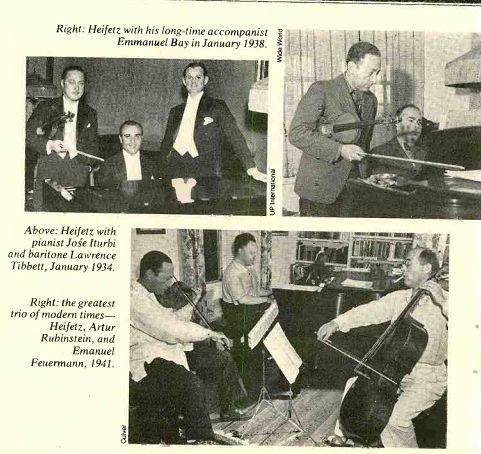

Right: Heifetz with his long-time accompanist Emmanuel Bay in January 1938.

Above: Heifetz with pianist Joie Iturbi and baritone Lawrence Tibbett, January 1934.

Right: the greatest trio of modern times Heifetz, Artur Rubinstein, and Emanuel Feuermann, 1941.

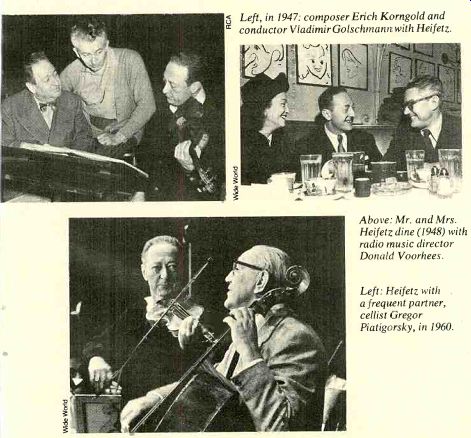

Left, in 1947: composer Erich Korngold and conductor Vladimir Golschmann with Heifetz.

Above: Mr. and Mrs. Heifetz dine (1948) with radio music director Donald Voorhees.

Left: Heifetz with a frequent partner, cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, in 1960.

----------

----------

Also see: