A Biography of Stephen Foster

Reviewed by Henry Pleasants

STEPHEN COLLINS FOSTER is the most famous American songwriter of the nineteenth century. He is more famous now than he was during his brief lifetime: 1826-1864.

But even today little is generally known about him beyond his name. In his recent book, Susanna, Jeanie and The Old Folks at Home, William W. Austin, Goldwin Smith Professor of Musicology at Cornell University, puts it aptly: "The 20th century public that knows Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair knows the name of Foster. It knows that he lived unhappily, dreaming of an ideal Victorian woman in the intervals between his listening to black singers.

The public has heard that he drank a lot and died alone, penniless. Just where and when he lived is hard to remember." This is certainly a curious state of affairs with an American of whom Professor Austin can say just as truthfully, noting the flattering attention paid to Foster by creative musicians as diverse in idiom and appeal as Anton Dvorák, Charles Ives, Ray Charles, Ornette Coleman, and Pete Seeger, that "no musical audience of the 20th century can come so close to representing a whole society as can the huge population that knows Foster's songs." As the title suggests, it is Foster's songs, and especially the unique universality of their appeal, rather than straight biography, that are the central subject of the book and the fascinating object of its author's widely ranging curiosity. He cannot, of course, escape biography, if only because we do not know Foster as we know, for example, Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, and Cole Porter and can –

------------

Susanna, Jeanie and The Old Folks at Home: The Songs of Stephen C. Foster from His Time to Ours, by William W. Austin. Macmillan, New York (1976), 420 pp., $17.95.

----------

not, therefore, relate the songs to the personality, the life, and the life style of the man who wrote them. Nor can we, as we can with them, determine precisely what social circumstances prompted the songs or be adequately aware of what they meant to those who sang them, heard them, learned them by heart, altered them, and loved them.

It is not that the bare biographical facts are unknown. It is rather that the several biographies, the most recent dating from 1934, pose more questions relative to the facts than they answer. So, for that matter, does Austin, whose work abounds in questions and conjecture. But, failing to find satisfactory answers in the "life," he looks for them in the "times," examining the songs in the musical, poetical, and social context of their own and subsequent eras. The examination has yielded clues, and these Professor Austin investigates with the insatiable curiosity of a Roman haruspex inspecting the entrails of a sacrificial lamb.

THERE is, to begin with, the beguiling phenomenon of a writer of "plantation songs" who never set foot on a plantation and almost certainly never heard a slave sing. Foster was born and brought up in reasonably comfortable middle-class circumstances in the suburbs of Pittsburgh. Aside from a short stint as bookkeeper for a brother's shipping firm in Cincinnati between 1847 and 1850, and a brief holiday excursion by boat to New Orleans in 1852, he spent most of his life in and around Pittsburgh and some of it in New York, where he died. Even the presumed Old Kentucky Home (once the property of a cousin of Foster's father, now a state museum in Bards town, Kentucky) he would seem to have known only fleetingly, if at all.

Foster's plantation songs were, in fact, minstrel songs, written for and sung by white men in blackface parodying blacks imitating-or parodying-whites. As the music of black Americans they were spurious. Even other minstrel songwriters, as Professor Aus tin points out, wrote songs more distinctively indigenous than Foster's.

Paradoxically, it may have been just this spuriousness that accounted for, or at least facilitated, their popular acceptance. They drew upon a nostalgic vision of the plantation not as it was or had been, but as it appeared and appealed to popular fantasy. And Foster gave to his subjects and his texts, probably unwittingly, an ambiguity that made it possible for the songs to serve the propagandistic fervor of both abolitionists and those who de fended slavery. The use of dialect-also spurious-gave an indigenous flavor to melodies, rhythms, and harmonies that were essentially European and, therefore, both familiar and acceptable to the white audiences for whom they were intended.

That was not the reaction of the musical establishment. However slight the suggestion of an indigenous Afro-American idiom may have been, it was enough at the time to arouse the furious indignation of the leading music critics, expressed in scathing language. Foster was hurt. He responded by concentrating on the type of sentimental ballad then fashion able. Most of his 200-odd songs belong to that category, Jeanie being a familiar prototype.

But they did not catch on as his plantation songs did, and it was this failure, probably, that broke him. As Professor Austin puts it in an admirably pithy summary: "He was swept along by what happened to Susanna, and baffled by what failed to happen to Jeanie." If the plantation songs fared better than the others, it may have been because the minstrel show was then, and would continue to be for another fifty years, the principal form of low brow entertainment in America, giving the songs a wider and more flattering exposure and the benefit of accomplished and popular performers. And if the plantation setting was phony, the music essentially European, and the poems ambiguous as to just who was sup posed to be singing to whom about what, the sentiments were genuine and very eloquently expressed.

Professor Austin is at pains to relate those sentiments to the facts of Foster's life-a sheltered, even pampered boyhood as the youngest of a large family, financial and probably emotional inadequacy as husband of a wife he loved, the economic vicissitudes of the profession of songwriting in pre-ASCAP days, etc. Most of all this is hardly more than plausible conjecture, but it matters little.

What mattered was-and still is-Foster's knack of evoking sensations, especially of melancholy and nostalgia, which he as an amiable loser certainly experienced, and which are common to all mankind.

[ books Received 4

William Billings of Boston, by David P. McKay and Richard Crawford, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. (1975), 304 pages, $16.00.

We are a country foolishly careless of its past, William Billings being an excellent case in point. This rather slender volume brings together perhaps all we shall ever know of the life of America's first, best native composer, an instinctive musician of unforgettable power and originality. I nominate this valuable book as the basis for a TV documentary on a lost, but still viable, musical tradition, and I nominate Billings' heart-pounding, hair-raising music, all three hundred or so pieces of it, as the fittest of celebratory anthems for our Bicentennial year. W.A.

Sing Your Heart Out, Country Boy, by Dorothy A. Horstman. E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., New York (1975), 394 pages, $12.95.

"Write your heart out" would be more accurate, as Dorothy Horstman is concerned with who wrote what country songs under what conditions. But it is a good and useful book, anyway, providing the lyrics of more than three hundred famous or once-famous country songs, with a paragraph above each one quoting the songwriter or a friend of the song writer on where the idea for the particular ditty originated. Remember Pistol Packing Mama? Molly Darling? Silver Dew on the Blue Grass Tonight? All here. N.C.

The Definitive Biography of P.D.Q. Bach, by Peter Schickele, Random House, New York (1976), 239-odd pages, $8.95.

P.D.Q. is, of course, the American Bach whose career seems likely to have been the most remark ably sustained flight of Witzelsuchl in the history of music. Prof. Schickele does that career full textual and iconographical justice in a book that tries hard to answer the question "Why?"

Nashville's Grand Ole Opry, by Jack Hurst. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York (1975), 404 pages, $35.

This is a colossal, fifty year history of one of the most colorful, per severing, and hard-working institutions in America. It includes everything about the Opry-the inner workings of management, past and present stars, the diverse styles of country music, the people who have supported it, and Nashville itself. Mr. Hurst has taken much of his information from old books and documents in the Country Music Hall of Fame Library; the bold pictures (and there are lots of them) in his book speak for them selves. If you ever laughed with Minnie Pearl, cried with Roy Acuff, or foot-stomped and finger-snapped to Bill Monroe, you will love this book. Diane Nakamura

Charles Ives and His America, by Frank R. Rossiter, Liveright, New York (1975), 420 pages, $15.

Perhaps the composer himself in spires it, but when the subject is Ives most musician-writers seem to sink immediately into a swamp of personalities, claim-staking, old scores, and petulant polemics. Historians can afford to be more dispassionate--Mr. Rossiter (who is one) therefore concentrates on Ives' particular historical problem, the frustrations of a creative artist caught at the tempestuous interface between the genteel tradition and the avant-garde. Seen in this way, Ives is less a composer than a political thinker who attempted to carry nineteenth century transcendental philosophy into the twentieth using music as a vehicle. Pity he failed. W.A.

Stars of Country Music, edited by Bill C. Malone and Judith McCulloh. University of Illinois Press, Evanston (1975), 476 pages, $10.

The lives and music of nineteen of the more important country-and-western per formers are described and analyzed by various writers between a foreword by folklorist D. K. Wilgus and a long piece on country mu sic since World War II by editor Bill Malone.

There is considerable useful information here, and the influence of those who broke ground for the nineteen featured performers is duly noted. Ralph Rinzler's piece on Bill Monroe, forerunner to a biography in the works, is especially good. N.C.

Scott Joplin and the Ragtime Era, by Peter Gammond, St. Martin's Press, New York (1975), 223 pages, $8.95. Mr. Gammond, mu sic editor of England's Hi-Fi News and Record Review, has produced a useful handbook for amateurs that describes the fascinating American musical tradition of which Joplin was a part and places it in history. There is an introduction by--who else?--Eubie Blake, a long quote from Charles Ives, excellent illustrations, and, best of all, an extensive discography of ragtime past and present, including the influencers (Gottschalk) and the influenced (Stravinsky). W.A.

The Opera File---OPERA AND THE BICENTENNIAL

AMERICA'S severest critics have usually been Americans themselves, and there are those among us who feel that we should spend 1976 not in celebrating two hundred years of independence, but in examining our collective conscience and repenting for our nation's sins. Abroad we have exploited other countries and meddled in their affairs. At home we have failed to provide equal rights to all our citizens. We have raped our continent.

We have permitted our cities to decay. In deed, our critics say, we have just been too had for too long to deserve a birthday party.

Well, perhaps. But I think our national ego has taken such a heating lately that we must consciously look for sources of self-esteem if we are going to have the strength to cope with our very serious problems. How can we hope that the children growing up today will correct the errors of previous generations if we don't give them some sense of pride in their own country? Although I am not unmindful of this country's shortcomings, I am not wearing sack cloth and ashes this year. Among other things, I'm enjoying the role opera is playing in the Bicentennial celebrations. West Germany has sent the Deutsche Oper to Washington to sing for us on our anniversary, and France is sending the Paris Opera in September. ( Italy had planned to send La Scala from Milan, but ran out of money.) My little project for the Bicentennial was to make a survey of American opera-it turned out to be a much bigger job than I realized.

According to the Central Opera Service, approximately 1,500 American operas have been composed since 1930 (almost all have been performed!), and there will be about one hundred world premieres this year, many of them Bicentennial commissions.

Last summer I went to Kansas City for the premiere of Jack Beeson's Captain finks of the Horse Marines (the first opera commissioned for the Bicentennial by the National Endowment for the Arts), hut I just haven't been able to keep up since. Premieres have been coming too thick and fast and in far away places-Thomas Pasatieri's Ines de Castro in Baltimore, Roger Sessions' Montezuma in Boston. and Dominick Argento's The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe in Saint Paul.

In addition to all the new operas being presented this year, many companies are reviving older American works, and those with native subject matter are especially popular now. The New York City Opera chose two of this type for its spring season, Beeson's Lizzie Borden and Douglas Moore's The Ballad of Baby Doe, both based on the lives of nineteenth-century Americans.

------ FRANCES BIBLE Simply magnificent in Baby Doe

Although a Massachusetts court acquitted Lizzie Borden of the ax murder of her father and stepmother, Beeson and his librettist Kenward Elmslie present her as guilty in a work of considerable dramatic power. I found the vocal line rather angular, but tolerable even to an ear as conservative as mine, and the orchestral score is exciting. It's rather like an American Elektra. Premiered by the New York City Opera in 1965, Lizzie Borden was recorded soon after by Desto with Brenda Lewis in the title role and Ellen Faull, Ann Elgar, Herbert Beattie, Richard Fredericks, and Richard Krause. That recording is still avail able and I recommend it.

The Ballad of Baby Doe is probably the most popular contemporary American opera.

Since its premiere at Central City, Colorado, in 1956 there has been only one season when it was not in the repertoire of at least one company. It is the story of Horace Tabor, who made a fortune in Colorado and divorced his wife Augusta to marry the beautiful young Baby Doe. The opera has some structural weaknesses, but the melodious score is pleas ant, and Baby Doe's final aria is beautiful enough to raise goose pimples (I've been humming it for weeks).

The recording of Baby Doe made by the NYC Opera in 1959, available for a time on MGM and later on Heliodor, has been out of print for years. Deutsche Grammophon is re releasing it in July, thus celebrating the Bicentennial, the Colorado centennial, and the twentieth anniversary of the opera's premiere. It features strong performances by Walter Cassel as Horace, Frances Bible as Augusta, and Beverly Sills as Baby Doe. A rather small-scale work, The Ballad of Baby Doe gains something from the intimacy of the recording medium.

IT gained similarly from the intimacy of TV when a performance at the NYC Opera was telecast this April in the distinguished Live from Lincoln Center series. The performance was good, and I found it an important operatic event. Ruth Welting as Baby Doe and Richard Fredericks as Horace made better impressions on television than they had in the opera house the week before, and Frances Bible, who has been singing the role of Augusta since the first production, was simply magnificent. She sang well, acted well, and projected a completely rounded characterization. The audience loved her, and so did I.

Half a dozen microphones and four specially developed cameras able to work at low light levels were placed in the theater so unobtrusively that they did not disturb the audience there. The results on the TV screen were excellent, and so was the sound, which was broadcast simultaneously in stereo on FM radio stations. The largest "simulcast" attempt ed in this country, the show went to more than sixty cities and was available to more than half the TV households in the country.

A wonderful sense of the excitement of going to the opera was communicated to the home viewer, and I'm convinced this is the way opera should be presented on TV-as a theatrical experience with stage scenery, a real audience, and high-quality sound. It's expensive, of course, and the costs of this broadcast were paid in the good new American way with contributions from a government agency, a foundation, and a private company. They were the National Endowment, the Charles A. Dana Foundation, and Exxon Corporation.

Among the finest things I've ever seen on television are the Martha Graham episode in Exxon's Dance in America series and The Ballad of Baby Doe in the Live from Lincoln Center series. Such television projects have taken giant steps forward in "nationalizing" the resources of our most important performing arts organizations by making them avail able free to literally millions of Americans across the country. That's something I think we can all be proud of. I am--I'm really glad this country was founded and that I was lucky enough to be born in it.

A FEW WORDS ABOUT Jazz

by CHRIS ALBERTSON

IT is said that a lady once asked the late Fats Waller what jazz was.

"If you have to ask," his reply allegedly went, "you'll never know." For many years, it was widely believed that jazz was conceived in Africa, born in New Orleans, weaned in the brothels of Storyville, and-in 1917, when the U.S. Navy closed down that infamous district-chased north by way of the Mississippi River to reach puberty in Chicago.

While there is a grain of truth in the old up-the-river-from-New Orleans story, it is, to put it mildly, a romanticized oversimplification. True, the term jazz (originally spelled jass) was first applied to a musical form that al most certainly took shape in New Or leans, but that music is as far removed from some current forms-which continue to be called jazz-as the works of Varese are from those of Vivaldi. If the term jazz is to cover all music that is traceable to the traditional New Or leans form of three-horn polyphonic improvisation, why should it not also be applied retroactively to cover the various forms of music from which the New Orleans style sprang? After all, ragtime, which seems to have had its origin in Missouri or Illinois, and the blues, which might well have originated in the Delta area of Mississippi, not only-preceded and greatly influenced the New Orleans style, but they, also bear a closer relationship to it than, say, the music of the Jazz Composer's Orchestra. The New Orleans musicians obviously heard ragtime and blues, and who is to say that they didn't also hear an early out-of-town band playing something akin to what we call New Orleans jazz? Real documentation did not begin until long after the form had been established, and we know that it all started in the Crescent City only be cause the people there told us so.

In recent years, many musicians, backed by some critics, have objected to the use of the term jazz, either be cause it did not seem relevant to the music they played or because of its alleged sexual connotation, or both.

Some have started calling the music Afro-American, but that, too, is a misnomer: a major ingredient of early jazz was European music (marches and quadrilles); many of the music's innovators were white, and when you think of it, is not the music of Brazilian blacks also Afro-American? The fact is that, though the forefathers of the earliest jazz pioneers most assuredly were conceived in Africa, the influence of African music on the music first known as jazz is hardly measurable; the field hollers and work songs of the South which predate New Orleans-style jazz-can without argument be traced to Africa, but the rhythmic patterns of the early New Orleans jazz bands so lack the complexities of African rhythmic patterns that any comparison is simply laughable. It is only in recent years that black American musicians have begun to assimilate anything approaching African rhythms, with the result that much of today's so-called jazz is, in fact, closer to African music than was the music of New Orleans some sixty or seventy years ago, and it should also be noted that the influence of European music on black American music has not waned.

Whether conducted by himself, Ernest Ansermet, or anyone else, Stravinsky's music is listed in the composer section of the Schwann catalog. On the other hand, Edward Kennedy Ellington's music appears in the composer section only when conducted by Gunther Schuller; Mr. Ellington's own recordings are listed in the jazz section.

Furthermore, Benny Goodman's recordings of Stravinsky's Ebony Concerto are listed in the composer section, and Ornette Coleman's Skies of America--recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra--is in the jazz section. Obviously the Schwann people are either making some kind of discrimination invisible to me, or they are simply confused. I suspect it's a bit of both, but when the world's leading re corded music catalog doesn't know what jazz is, how can anyone else be expected to? Perhaps we would all do best to discard the terminology, enjoy the music, and bear in mind the reply Big Bill Broonzy gave to Studs Terkel when asked if the blues is folk music: "It's all folk music, 'cause horses don't sing."

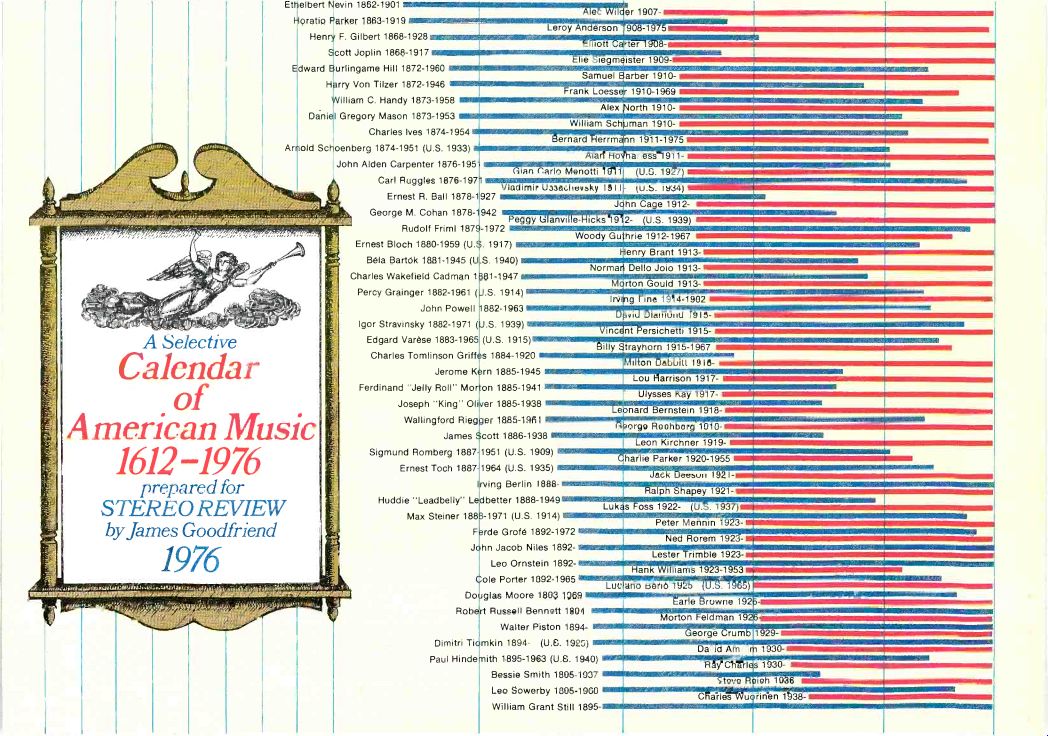

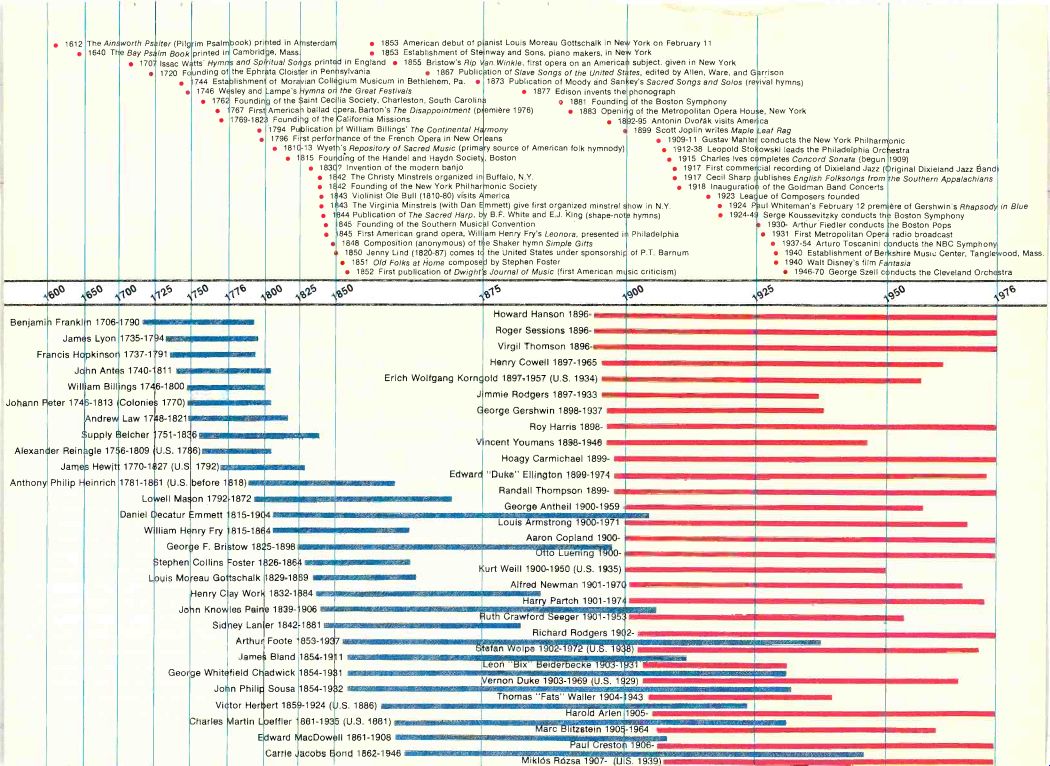

A Selective Calendar of American Music 1612-1976

Prepared for STEREO REVIEW by James Goodfriend 1976

1612 The Ainsworth

1640 The Psalter Bay Psalm

1707 (Pilgrim Book Isaac Watts'

1720 Funding Psalmbook) printed in Hymns of 744 Establishment.

1746 Wesley

1762 printed Cambridge, and Spiritual the Ephrata and Founding 767 First 1769-1823 in Amsterdam Mass Songs Cloister of Mora Lampe's of the Americas Founding

.1794 Publication

1796 Fist

181C-13

1815 printed in Pennsylvania ian Collegium Hymns on Saint Cec ballad c of the performance Wyeth's Foundrng

183C?

1E42

1842

1843

1843

1844

1853

American debut of p

1853 Establishment of Ste in England 1855 Bristow's Rip Van.

1867 Publication Musicum in Bethlehem, Pa.

the Great Festivals lia

Society, Charleston, South Carolina

pera, Barton's The Disappointment (premiere California Missions of William Billings' The Continental Harmony of the French Opera in New Or Repository of Sacred Music (primary of the Handel and Haydn Society, Invention of the modern banjo The Christy Minstrels organized in Founding of the New York Philharmonic Violinist Ole Bull (1810-80) visits America The Virginia Minstrels (with Dan Emmett) Publication of The Sacred Harp, by 845 Founding of the Southern Musical 1845 First. American grand opera, Will 1848 Composition (anonymous) of the

1850 Jenny Lind (1820-87) comes to

1851 Old Folks at Home composed

1852 First publication of Dwight anist Louis Moreau Gottschalk in New nway and Sons, piano makers, in New Winkle, first opera on an American of Slave Songs of the United States, 1873 Publication of Moody and Sankey's

1877 Edison invents the

1881 Foundinc 1976) 1883 Openir

18-92-95 a eans source of American folk hymnody) Boston Buffalo, N.Y.

Society give first organized minstrel show B.F. White and E.J. King (shape-nots Convention am Henry Fry's Leonora, presented in Shaker hymn Simple Gifts the United States under sponsorship by Stephen Foster s Journal of Music (first American mt York on February 11 York subject, given in New York edited by Allen, Ware, and Garrison Sacred Songs and Solos (re,ival phonograph of the Bostcin Symphony g of the Metropolitan Opera House, Antonin Dvotak visits America 1899 Scott Joplin writes Maple

1909-11 Gustav Mahler

1912-38 Leopold Stokowski

1915 Charles Ives c

1917 First commercial

1917 Cecil Sharp

1918 Inauguration

1923 Leap in N.Y. 1924 Paul hymns)

1924-49 Philadelphia of P.T. Barnum sic criticism) hymns) New York Leaf Rag conducts the New York Philharmonic leads the Philadelphia Orchestra mpletes Concord Sonata (begun recording of Dixieland Jazz (Original publishes English Folksongs from of the Goldman Band Concerts ue of Composers founded Whiteman's February 12 prem Serge Koussevitzky conducts the 1 1930- Arthur Fiedler conducts

1931 First Metropolitan Opera

1937-54 Arturo Toscanini

1940 Establishment of. Berkshire

1940 Walt Disney's film Fantasia

1946-70 George Szell conducts 1909) Dixieland Jazz Band the Southern Appalachians are of Gershwin's Rhapsody Boston Symphony the Boston Pops radio broadcast the NBC Symphony Music Center, Tanglewood, the Cleveland Orchestra in Blue Mass

-----------

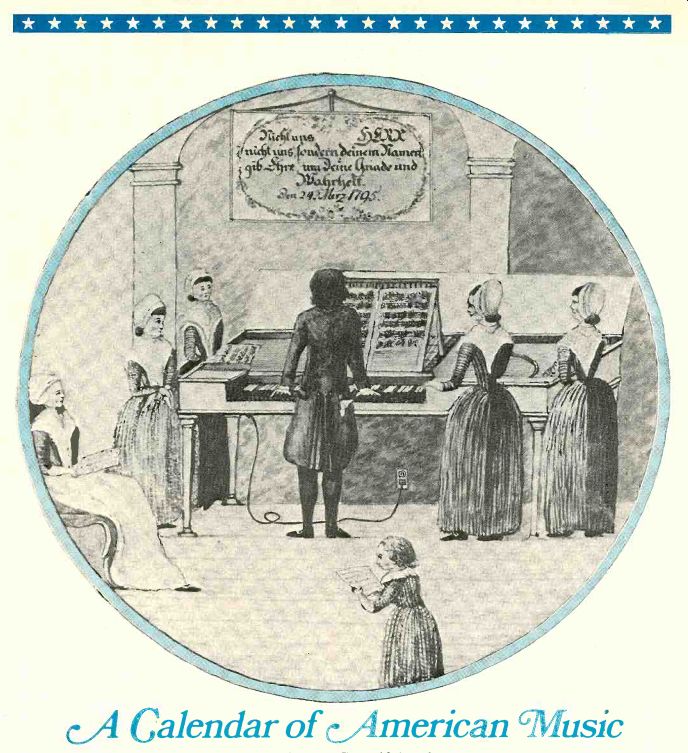

A Calendar of American Music

by James Goodfriend

The illustration above (courtesy the Moravian Music Foundation) is a birthday greeting given to Moravian Bishop Jacob van Vleck in 1795. He is pictured accompanying a group of girls, probably from the Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, School for Young Ladies, of which he was principal.

IN contemporary business terminology, American music would be referred to as a conglomerate rather than a company or a corporation, for, like business conglomerates, American music deals with a multiplicity of un related products rather than with a traditional "line" of one kind of product.

We are, for the most part, an immigrant nation, and there are an incredible number of musics that can all, with relatively equal justification, be called "American." Rationalizing what ought to be the limits of the field, then, is a tricky business, and an attempt to create some sort of historical ordering of American musical manifestations leads to no more than a simple chronology. The succession of clear-cut stylistic periods and the obvious influence of one com poser on another characteristic of European musical history are largely absent here. It may be interesting to know that the lives of Carrie Jacobs Bond and Elliott Carter overlap by almost forty years, but nothing significant about either of them can be drawn from that bit of information. What is significant about it is the pairing itself, that such polar opposites are frequently coincident in American music. He who would put together a calendar of the subject, therefore, can have no single criterion for inclusion, but must constantly weigh apples against oranges and tangerines, not to mention the lemons. Still, how appropriate! Pragmatism is an American philosophy.

THIS calendar, then, cannot really stand on its own, for it needs some defense, some account of why certain people and things were included and others, equally or even more worthy, were not. To begin with, the numerically-minded viewer will see that there are precisely fifty events mentioned and that the time span from 1600 to 1976 has been marked off into thirteen artificial periods, thus making the whole calendar an analog for the American flag.

This, I hasten to add, was not intentional but purely unconscious, and, though it will do nothing else, it should serve as testimony to the author's inherent patriotism in putting the thing together at all.

So far as the specifics go, the selection of events fairly well explains itself.

Each "event" (some of them are durations) is something of musical importance in the history of the United States. Some are unique; some are representative of other, similar events that occurred contemporaneously or subsequently. Some refer to music important in itself; some refer merely to types of music, or to the earliest or most famous examples of whole genres of music.

But virtually all are included because they had an impact, in one way or another, on music in America-its composition, performance, style, taste, popularity-even though the "event" itself may not have been American in origin.

The names require a different explanation. In general, this is a chart of composers and creative musicians rather than of performers, theoreticians, critics, teachers, or others who might have been influential in their own ways on American music. Therefore, few of the idols of American pop music are represented, though in a calendar drawn on other grounds they would be prominent. American classical per forming musicians are likewise absent, even though in many cases their names are more familiar than those of some composers included. Conflicting demands become particularly severe in jazz. The rule is bent a little here, but the nod still goes to the creators over the interpreters (Billy Strayhorn rather than Cootie Williams). Such inventive geniuses of improvisation as Louis Armstrong, however, despite minor outputs of actual written compositions, just have to be included.

------- ...there are an incredible number of musics that can all, with relatively equal justification, be called "American. -----------

Many of the names before the twentieth century will be unfamiliar to the reader, and he will simply have to take the calendarer's suggestion that there are significance and interest there and perhaps look into the matter for him self. Anthony Philip Heinrich ("the Beethoven of Kentucky") and Supply Belcher ("the Handel of Maine") may not equal their namesakes, but they were talented men who tried to make an individual music for their neighbors, the American people. The inclusion of such other names as Daniel Decatur Emmett and James Bland becomes perfectly clear when we know that they composed, respectively, Dixie and Carry Me Back to Old Virginny, among other "hits." The big names justify themselves with no trouble. Of the smaller names, one can make only a representative selection, and so the composer of I Love You Truly (Carrie Jacobs Bond) serves also to represent the composer of Oh, Promise Me (Reginald de Koven), and Huddie Ledbetter stands for a host of creative black bluesmen.

Although, as Bernard Jacobson mentions elsewhere in this issue, the line between the classical and the popular is extremely difficult to draw in American music, this calendar is directed general ly toward classical composers and generally toward men who have either completed their lives' work or who have already established their reputations as important figures. That will ex plain why the youngest man represent ed is a thirty-eight-year-old classical composer and why younger men, in all fields, are not. It will also explain although it may not excuse it to some readers-why some fairly obscure composers are here in relative abundance, while jazz, pops, country-and western, and film music are represent ed only by a comparatively few out standing names. Still, those areas of music are represented.

IF there is one particular emphasis of this calendar, it is the continuing importance to American music of immigrants and visitors from abroad. Peter, Reinagle, and Hewitt in the eighteenth century, Heinrich, Herbert, and Loeffler in the nineteenth, Grainger, Bloch, Schoenberg, Bartok, Hindemith, Varese, and Stravinsky in the twentieth, among others, all influenced the course of American music as the idea of America influenced their music.

Though music in America is not the derivative European thing it once was, the continuing admixture of influences from outside, as well as the recombination of all the different musical elements already present in our musical culture, is an intrinsic part of musical development here. Whatever else the world may say about it, no one could ever accuse American music of being inbred.

A Basic Library of American Music

A (Basic) Librarian of American Music on Records must give careful thought to defining just what his title implies. Even if he ends by deciding he can get along without a simple answer to the question of what is meant by "American" and "Music," at the very least the question of whether the question needs to be asked needs to be asked.

First of all, the two halves of the question are inextricably linked, since the sheer variety of musical creation and experience in the United States is itself a phenomenon unparalleled else where. "Only here," said Virgil Thom son, "do composers write in every possible style and does the public have ac cess to every style." As the music I have chosen for this Basic Library shows, the consequence for a foreign critic like myself, whose prime concern is what we fatuously call (for want of a better word) "serious" music, is that he must take far greater account of the sounds made at revival meetings and by marching bands and along Tin Pan Alley and in Civil War-epoch drawing rooms and turn-of-the-century Saint Louis brothels than he would of any comparable popular or quasi-popular emanations in the music of any other countries.

So far, so flexible. But even when you have sorted out roughly how many purely musical genres you are prepared to admit to your list, the awkward puzzle remains: where to draw the line on "American"-ness. Thomson, again, argues that to write American music "All you have to do is to be an American and then write any kind of music you wish." But though that may be un answerable on its own terms, it is not of much practical help for our present purposes. For who, ladies and gentle men, is an American? Just how young and unformed did Stravinsky and Schoenberg and Hindemith and Varese and Block and Milhaud and Martial and Kr'enek (or, for that matter, James Hewitt, Gian Carlo Menotti, and Lukas Foss) have to be when they reached your shores in order to qualify as "American composers"? I have sidestepped the difficulties by taking the philosophically more dubious line that American music is not simply music by Americans, but a certain kind of music (by Americans). As may be seen from the listings below, such an approach permits a sort of fundamental anatomy of musical Americanism to emerge. It embraces three qualities: physical exuberance, large ness of gesture, and a tendency toward ...

-------------

There is no painter more American than the late Thomas Hart Benton, and it is unlikely that any painting more ably characterizes American music than his mural, The Sources of Country Music," which graces (with the help of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Tennessee Arts Commission) Nashville's Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. In it can be found intimations of everything from William Billings' fuging tunes to George Crumb's Echoes of Time and the River-a title borrowed, of course, ,from Thomas Wolfe, most American of novelists.

--------------

...kitsch (the last of these, as any connoisseur of Berlioz, Mahler, or Strauss will immediately recognize, is of course neither exclusively American nor in any necessary sense a negative value).

This characterization is advanced with some diffidence. Critics like Thomson have, I know, put forward lists of much more detailed and scientific-sounding criteria for Americanism, running to such items as the non-accelerating crescendo and the prevalence, even when not explicit, of a constant underlying eighth-note pulse. Thomson on American music, of which he is himself one of the foremost practitioners, is a writer of vast knowledge and brilliant perception. Yet I cannot help feeling, on the evidence, that his formulations admit of too much qualifying and demand too much excepting to be cogent. The three vaguer attributes I have named apply more firmly, I submit, to almost all the com posers listed below, however diverse their aesthetics and their spheres of activity.

Almost-but not quite-all, for it would not be really British of me to follow my own rules with complete consistency. Roger Sessions, whom I didn't think it reasonable to exclude, cannot perhaps be characterized by the three qualities with absolute conviction (though it can be argued that the grandeur, physical immediacy, and occasional deliberate raucousness of his orchestral writing set him apart in a thoroughly American fashion from his European linguistic models), and some thing of the same reservation might be expressed about John Cage and Milton Babbitt.

But those three strands are evident in the others from the very beginning. For example, you don't have to wait for Bernstein, or even Gottschalk, to en counter kitsch in the music of America.

It is right there in Billings, along with a propensity to skip and jump at the slightest provocation that would be in congruous in most European religious music. Skipping and jumping, and a variety of other overtly physical acts, characterize the whole range of American musical experience-which suggests why so large a proportion of the nation's music has taken on theatrical means of expression, and why, in particular, America has perfected the loose-limbed Broadway musical and made the greatest single contribution of any country to the art of dance in this century.

Charles Ives, the man who since his death has come to be widely regarded as a standard-bearer for American composers, is typical of them in this respect. Even his most loftily conceived works resemble nothing so much as a glorious gallimaufry of physical movements, march and quickstep and barn dance and ragtime and gallop. The rich patrimony of New England hymnody is there too. And all the diverse elements, like the hundreds of ethnic groups in contemporary America, coexist--with degrees of tension, certainly, but also with a new, exciting, and unique celebration of multifariousness over and under all. For American music, like America itself, though it may exalt the Idea of Order, also accepts the Reality of Chaos, greeting it in a way the ancient Stoics would have understood: by singing-and dancing-in the teeth of the gale.

For example:

EARLY AMERICAN VOCAL MUSIC:

New England Anthems and Southern Folk Hymns. Law: Bunker Hill. Read: Newport.

Morgan: Judgment Anthem: Amanda. Billings: I Am Come into My Garden; I Charge You; I Am the Rose of Sharon; O Praise the Lord of Heaven. Ingalls: Northfield.

White: Power. Lewer: Fidelia. Robison: Fiducia. Dare: Baylonian Captivity. Chapin: Rockbridge. Anon.: Washington; Triumph;

-------

"Skipping and jumping, and a variety of other overtly physical acts, characterize the whole range of American musical experience..."

Messiah; Canaan; Springhill; Concert; Lonsdale; Animation; Pilgrim's Farewell.

Western Wind Vocal Ensemble, with guest artists. NONESUCH H 71276 $3.96.

BILLINGS: I Am the Rose of Sharon; David's Lamentation; The Bird; Kittery; Hopkinton; When Jesus Wept; The Lord Is Risen; A Virgin Unspotted; Boston; The Shepherd's Carol; Creation; Connection; Consonance; Jargon; Modern Music; Cobham; Morpheus; Swift as an Indian Arrow Flies;

Chester; Be Glad Then America. Gregg Smith Singers, Gregg Smith cond. COLUM BIA MS 7277 $6.98.

THE ORGAN IN AMERICA. Anon.: Capitain Sargent's (Light Infantry Company's) Quick March; The London March; The Unknown. Phile: The President's March. Billings: Chester. Selby: Fugue or Voluntary, in D Major. Moller: Sonata in D Major. Hewitt: The Battle of Trenton. Michael: Six Movements from the Instrumental Suites.

Brown: Rondo in G Major. Yarnold: March in D Major. Shaw: Trip to Pawtucket. Ives: Variations on " America." E. Power Biggs (organ). COLUMBIA MS 6161 $6.98.

A tanner by trade and a composer by passionate avocation, William Billings (1746-1800) may not have invented the vein of salty humor often thought of as a Yankee characteristic, but he was the first musician to express it with a touch of quirky genius. A sort of musical Will Rogers, Billings ranged from down home sentiment in his Biblical settings to a blend of religious and patriotic fervor in the famous hymn-tune Chester.

The reach-me-down but effective flights of contrapuntal fancy in the so called fuging tunes are irrepressibly juxtaposed with cheerful jigs, and the wrong-note dissonance of the satirical Jargon inaugurated the American tradition of snook-cocking effrontery exemplified more than a century later--by the notorious final "chord" of Ives' Second Symphony. The Gregg Smith Singers biff out their attacks a touch too heftily for my taste, but their performances are otherwise admirably fresh and unaffected.

If I had to limit myself to a single disc featuring Billings, I think I would choose Nonesuch's multi-composer anthology. In the one work common to both records, I Am the Rose of Sharon, the Western Wind performers (singing one voice to a part) delightfully evoke the innocence of the music where Smith stresses its vigor, and the collection also includes several non-Billings pieces of scarcely lesser charm and, in the case of Justin Morgan's fine Judgment Anthem, of an equally arresting idiosyncrasy.

The Biggs collection is a pleasantly personal exploration of early American keyboard pieces, played on tracker action instruments in New England, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina, set off by a diverting excursion into the late nineteenth century with Ives' iconoclastic Variations on America. The whole is accompanied by a well-illustrated leaflet. One of the musicians represented, David Moritz Michael, was a member of the American Moravian school of composers, to which another Columbia record, Odyssey 32 16 0340, is devoted. Though the music sounds more eighteenth-century European than American, there are some at tractive pieces to be found in the collection, including an imposing anthem by Johann Friedrich Peter and a string trio by the gifted Pennsylvanian John Antes sympathetically played by members of the Fine Arts Quartet. The choral performances conducted by Thor Johnson are, however, impossibly inflated.

FOSTER: Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair; There's a Good Time Coming; Was My Brother in the Battle?; Sweetly She Sleeps, My Alice Fair; If You've Only Got a Moustache; Gentle Annie; Wilt Thou Be Gone, Love?; That's What's the Matter; Ah! May the Red Rose Live Always; I'm Nothing but a Plain Old Soldier; Beautiful Dreamer; Mr. and Mrs. Brown; Slumber My Darling; Some Folks. Jan DeGaetani (mezzo soprano); Leslie Guinn (baritone); Gilbert Kalish (piano, melodeon); Robert Sheldon (flute, keyed bugle); Sonya Monosoff (violin). NONESUCH H 71268 $3.96.

GOTTSCHALK: The Banjo; The Dying Poet; Souvenir de Porto Rico; Le Bananier; Ojos Criollos; The Maiden's Blush; The Last Hope; Suis Moi; Pasquinade; Tournament Galop; Bamboula; La Savane; Grand Tarantelle for Piano and Orchestra (arr. Hershey Kay); Symphony, "A Night in the Tropics." Eugene List (piano, in the solo pieces); Reid Nibley (piano, in the Grand Tarantelle); Utah Symphony Orchestra, Maurice Abravanel cond. VANGUARD VSD 723/24 two discs $6.98.

JOPLIN: Maple Leaf Rag; The Entertainer; The Ragtime Dance; Gladiolus Rag; Fig Leaf Rag; Scott Joplin's New Rag; Euphonic Sounds; Magnetic Rag; Elite Syncopations; Eugenia; Leola-Two-Step; Rose Leaf Rag-A Rag Time Two-Step; Bethena-A Concert Waltz; Paragon Rag; So lace-A Mexican Serenade; Pine Apple Rag. Joshua Rifkin (piano). NONESUCH HB 73026 two discs $7.92.

The Foster is Stephen and the Joplin is Scott. It is the music of such composers as' these and Louis Moreau Gottschalk that makes the line of demarcation between "classical" and "popular" in American music impossible to draw with any exactitude.

The music in this group ranges from minor classical in the Foster songs to major popular in the Joplin piano rags. And it is worth noting that the popular tradition is by no means the weaker in purely musical value: Foster's songs, though charming in their sentimental manner and un deniably an essential segment of any history of American music, are small beer next to the formally circumscribed but marvelously varied and often surprisingly profound Joplin pieces.

----------- 74

New Genuine Orthophonic Victrola MODEL FOUR-FORTY Newest Victor creation. A handsome console type instrument, in mahogany finish. Brings into your home the finest in music and song. The acme of musical perfection_ Hear it.

---VICTROLAS i85 to $1000 Convenient Terms

-------

It is particularly instructive in this musical investigation to compare the best of ragtime with what "serious" American composers had achieved in the preceding one hundred years. Alan Mandel's superbly played but compositionally thin three-record anthology of American piano music on Desto DC 6445/47 comes to life only when it reaches Joplin and his colleagues Paul Pratt, Joseph Lamb, and Artie Matthews, and with the exception of Virgil Thomson (of whom more later) the twentieth-century composers that follow are nothing like so striking.

Jan DeGaetani and her colleagues catch Foster's cozy but genuine sub Schubertian grace to a nicety in the Nonesuch collection. Not everyone likes Joshua Rifkin's magisterial way with Joplin, but in my judgment it enhances the music by treating it exactly as seriously as the composer did.

Gottschalk was a curious figure, not unlike the virtuoso half of Liszt in the dazzling career he pursued as composer-performer-showman. His penchant for exploring ethnic musical styles led to some engaging results in his solo piano pieces and again in the samba rhythms of A Night in the Tropics. The occasional whiff of Chopin or even Berlioz may remind us of Gottschalk's lesser stature, but there is nonetheless a real composer behind the razzmatazz, and the Vanguard set is a use ful compendium of his best work.

It would, I suppose, have been appropriate to include some Sousa on this nineteenth-century shelf of the Basic Library. For my taste, an entire side of the March King's relentless energy is as hard to listen through as several sides of Joplin are easy, so I will simply mention the brilliantly efficient discs of the stuff made some years ago by (1) Paul Lavalle and the Band of America (MGM SE 3976) and by (2) Frederick Fennell and the Eastman Wind Ensemble (Mercury 75004) and leave it at that.

GERSHWIN: Porgy and Bess. Willard White, Leona Mitchell, McHenry Boat wright, Florence Quivar, Barbara Hendricks, Barbara Conrad, Frangois Clemmons, others; Cleveland Orchestra, Chorus, and Children's Chorus, Lorin Maazel cond. LONDON OSA 13116 three discs $20.94.

BERNSTEIN: Music for the Theater. Dances from " West Side Story"; Facsimile; Overture to "Candide"; Three Dances from "On the Town"; Fancy Free; Two Medita tions from "Mass." Orchestra from the opening of the Kennedy Center for the Per forming Arts (in Mass), New York Philhar monic (in all other works), Leonard Bern stein cond. COLUMBIA MG 32174 two discs $7.98.

ELLINGTON: Latin American Suite. Duke Ellington and His Orchestra. FANTA SY 8419 $6.98.

--------

These three are pre-eminent among the composers who have continued to straddle the popular/classical categories in our own century. Gershwin did it, I think, less convincingly than the other two, for I find his "symphonic" works, and most glaringly the Piano Concerto, stiff and unnatural: he really did think of the classical forms as mere molds, sitting around waiting to have music poured into them. Porgy and Bess, by contrast, is Gershwin at his inspired and unforced best, and my im mediate impression of Lorin Maazel's sumptuous new set-the first uncut re cording of the opera, and the first in true stereo-is that it effortlessly leaves such competition as there is trailing far behind.

Ellington's inclusion under this heading may at first blush be questioned, since he does his category-straddling without any superficial emulation of classical styles and forms. He was, however, a composer of symphonic scope and possibly classic stature. The work of his great 1940 band is, oddly, more skillfully handled in some European releases than in the U.S. catalogs, and for the American collector I have therefore selected instead one of the most colorful of his last works.

Bernstein has an equally comfortable foot in both musical camps-or at least he did before he became too "serious" to write musicals like Candide or West Side Story any more. A sample of his symphonic work is listed later on, but this theater collection sums up his most individual contribution to American music. (Incidentally, few critics would rate the "serious" Bernstein anywhere near Aaron Copland, but some of the slower sections of On the Town successfully speak the same harmonic and atmospheric language as Copland's bal let Appalachian Spring, which had its premiere a matter of weeks before the Bernstein work.) One other piece of American musical theater I cannot resist mentioning is The Cradle Will Rock, by that underrated composer Marc Blitzstein, who carried a banner for American leftism in its golden age of innocence, the Thirties. The work is available in a two-disc CRI set, S 266.

THE EARLY STRING QUARTET IN THE USA. Mason: Quartet in G Minor, Op. 19 (based on Negro Themes). Griffes: Two Indian Sketches. Franklin: Quartet for Three Violins and Cello. Foote: Quartet in D Major, Op. 70. Chadwick: Quartet No. 4, in E Minor. Hadley: Piano Quintet in A Minor. Loeffler: Music for Four Stringed Instruments. Kohon Quartet; Isabelle Byman (piano, in the Hadley). Vox SVBX 5301 three discs $10.98.

Returning to the path of strictly classical duty, I can find no clearer picture of American chamber music around the turn of the last century than that presented by this well-engineered Vox Box.

----- "the music of such composers makes the line of demarcation between 'classical' and 'popular' in American music impossible to draw with any exactitude." ----

The Franklin--much earlier in date than all the others--is Benjamin, no less, and this quaint suite of dances, played entirely on specially tuned open strings, may well be genuinely his. The Foote and Hadley works are academic in the boring sense, the Loeffler inflated in the manner of an American Chausson (though not, perhaps, quite so soupy), and the Griffes no more than an atmospheric hint of its composer's real talent. But Daniel Gregory Mason handles his spirituals with scarcely less than Dvorkian skill, and the quartet written by George Chadwick in 1895 is a real find-genial, witty, and endowed, in its third movement, with a positively peachy trio section. The Kohons are not always perfectly in tune, but they have this music in their bones, and they play it with irresistible zest.

IVES: Three Places in New England. Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy cond. Washington's Birthday. New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein cond. Robert Browning Overture. American Symphony Orchestra, Leopold Stokowski cond. Columbia MS 7015 $6.98.

IVES: Piano Music (complete). Alan Man del (piano). DESTO 6458/61 four discs $27.92.

VARESE: Ameriques; Ecuatorial; Nocturnal. Arid Bybee (soprano, in Nocturnal); Bass Ensemble of the University-Civic Chorale, Salt Lake City (in Ecuatorial and Nocturnal); Utah Symphony Orchestra, Maurice Abravanel cond. VANGUARD SRV 308SD $3.98.

Ives and Varese were the two great originals of modern American music-the one as native an American as you could find, assembling his language from the raw blocks of American experience, aural and otherwise, wherever he found them, the other an immigrant (he arrived in 1916 at the age of thirty-one), inventing an entirely abstract yet poet cally evocative vocabulary out of thin air and rivaling Stravinsky in freshness of ear and time-scale.

The Ives discography is now extensive, yet still, to my mind, oddly un satisfactory. For, rather than the sym phonies, which perhaps make the biggest immediate impact, I find that the piano music, violin sonatas, and songs offer the more lasting Ivesian rewards, and only in Alan Mandel's comprehensive set of the piano music does the phonograph deal adequately with any of these sections of his output. Paul Zukofsky is unimpeachably scholarly but pinched of expression and surprisingly sour of intonation in the None such set of the violin sonatas (no match for the sweet-toned Rafael Druian/ John Simms set that used to be avail able on Mercury). And I would pick John Langstaff as the likeliest man to remedy the present patchy representation of the songs--he was the first and last singer I have heard do a really worthy Charlie Rutlage, maybe the best of the 114 Songs and suggestive of a twentieth-century Charles Dibdin (to choose a very British parallel) in its circumscribed but touching truth of ex pression. Pending improvement in these areas (a worthy Bicentennial task, I would have thought, for any American company), the Mandel set, together with the colorful orchestral anthology on Columbia, provides the best all-round picture of Ives. There is also an attractive Nonesuch disc (H 71306) of the two string quartets played by the Concord String Quartet.

The catalog listings of Varese are more concentrated but also, on balance, better. The Vanguard record I have chosen, coupling the large-scale Ameriques with two mysterious, dramatic, often Messiaenic vocal pieces, won by a short head in a contest among several good and variously coupled collections by Cerha on Candide, Weis berg on Nonesuch, Simonovitch on Angel, and Craft on Columbia.

There was, by the way, another celebrated "great original" on the American scene in the shape of Carl Ruggles.

I am afraid I find him original but not great. There is a striking parallel here with the Englishman Havergal Brian: both men were born in 1876, lived into their nineties largely neglected, and have subsequently been "revived" amid much fanfare about the uncompromising spareness and integrity of their music. On inspection, the spare ness and the integrity sound to me more like roughness of technique-or, to put it plainly, sheer clumsiness. But if you want to investigate Ruggles at his best, try the succinct Angels, a brass piece conducted by Lukas Foss on Turnabout TV 34398S and coupled with attractive short works by Ives and Copland and the Mason quartet listed in the previous section.

---------------

VIOLIN OUTFIT Beautifully toned instrument in fine violin case. Bow, book of instructions, book of solos, set of strings, chin rest, E string adjuster, rosin, mute and music stand. $39.50

----------------

HOWARD SPECIAL TENOR BANJO WITH RESONATOR

A fine high grade banjo made of the best materials with fine inlaid resonator. Complete with velvet lined case.

Convenient Terms

THOMSON: Suites from Film Scores. The River; The Plow That Broke the Plains. Sym phony of the Air, Leopold Stokowski cond.

VANGUARD VSD 2095 $6.98. [See also: Best of Month, page 83.]

COPLAND: El Salon Mexico; Billy the Kid-Suite; Rodeo Suite; Appalachian Spring-Suite. New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein cond. COLUMBIA MG 30071 two discs $7.98.

HARRIS: Symphony No. 3.

BERNSTEIN: "Jeremiah" Symphony. Jennie Tourel (mezzo-soprano, in the Bernstein); New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein cond. Columbia MS 6303 $6.98.

CARTER: String Quartets Nos.1 and 2. Composers Quartet. NONESUCH H 71249 $3.96.

BARBER: Knoxville, Summer of 1915; Antony and Cleopatra (excerpts). Leontyne Price (soprano); New Philharmonia Orchestra, Thomas Schippers cond. RCA LSC 3062 $6.98.

AMERICAN STRING QUARTETS, 1900-1950. Gershwin: Lullaby. Copland: Two Pieces. Ives: Scherzo. Thomson: Quartet No. 2. Sessions: Quartet No. 2. Piston: Quartet No. 5. Hanson: Quartet in One Movement, Op. 23. Mennin: Quartet No. 2. Schuman: Quartet No. 3. Kohon Quartet. Vox SVBX 5305 three discs $10.98.

Here we launch ourselves into the twentieth-century American main stream. The grouping above might easily be summed up as "The Boulangerie and Friends": nearly half of the com posers included were students of Nadia Boulanger in Paris, and almost all of them write music marked by open textures, eupeptic vigor, skilled craftsmanship, and a vein of frank American sentiment often related in musical terms to the nation's still-pervasive hymnody.

Leaving out of account Gershwin and Ives, who are here represented only by filler-size miniatures, the two biggest talents, in my view (and I am aware that this will surprise many Americans), are Virgil Thomson and Elliott Carter. The two could hardly be more different. Thomson has taken the cult of musical simplicity to its extreme, reacting deliberately-in a way that some find intellectually suspect against the saturation point of complexity and dissonance reached by much modern music. But he is no primitive. The mastery of contrapuntal and other techniques, for all that they are un-emphatically deployed, is complete, in sharp contrast to the tonic-and-dominant-thumping brutism of such other minimalist figures as Carl Orff. The lack of modern recordings, or in most cases any recordings at all, of Thomson's songs and operas urgently needs to be remedied.

Carter, on the other hand, might be taken as an exemplar of modern complexity, preoccupied as he has been with the temporal element of music and with sometimes rather pretentious quasi- metaphysical concepts. He is at his eloquent best in his First Quartet. But the Nonesuch disc somewhat cruelly demonstrates how, in the eight years that separate it from the Second, theory took over from inspiration: indeed, most of Carter's later works seem to me to add up to very little more than paper-music.

Roy Harris (represented at his peak by the Third Symphony) and Samuel Barber are others who have suffered a sad decline, Harris into fuzzily sentimental modal moonings and Barber, after the small pure flame of Knoxville, into the apotheosis of kitsch (to be found in its least agreeable form in An tony and Cleopatra).

For the rest, the oddest man out is Roger Sessions, whose stylistic affinities are Austro-German rather than French or, in any specific way, American. He is included here rather than in a more appropriate place because the discography is, again, woefully inadequate-no recordings of the operas Montezuma and The Trial of Lucullus or of any but one of the weaker of the late symphonies, and only an antique electronic stereo disc of the best of the early ones, No. 2. Elsewhere in the Vox quartet set, the Hanson is undistinguished neo-Romantic mush, but Piston (whom I generally find a rather cold fish), Mennin, and Schuman are all in excellent, inventive form.

And that, apart from Bernstein the composer, who has already been discussed, leaves Copland. Give or take a touch or two of romanticizing in the performances, this much-loved com poser's best works are usefully assembled in the Columbia "Copland Album." Supplemented by the sumptuously vulgar Salon Mexico (kitsch at its most enjoyable), these ballet suites breathe the authentic American combination of lyricism, brashness, and innocence; they are utterly genuine in feeling where such intellectually more ambitious Copland works as the Piano Variations and the tedious orchestral Connotations and Inscape seem contrived. (The complete original score of Appalachian Spring for chamber orchestra has, by the way, been recorded under the composer's direction on Columbia M 32736, but Copland, though a fun pianist, is not much of a conductor, even of his own works.)

CAGE: Concerto for Prepared Piano and Chamber Orchestra.

FOSS: Baroque Variaions. Yuji Takahashi (prepared piano, in the Cage); Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, Lukas Foss cond. NONESUCH H 71202 $3.96.

BABBITT: String Quartet No. 3.

WUORINEN: String Quartet. Fine Arts Quartet. TURNABOUT TV-S 34515 $3.98.

CRUMB: Ancient Voices of Children. Jan DeGaetani (mezzo-soprano); Michael Dash (boy soprano); Contemporary Chamber Ensemble, Arthur Weisberg cond. NONESUCH H 71255 $3.96.

This may seem a sparse representation for America's almost frenetically productive avant-garde, but the reason is simply that I cannot yet recognize many of its creations as basic. Foss, unlike most of this company, has a telling wit: his Baroque Variations, three essays in re-composition (of Handel, Scarlatti, and Bach) that can still stir a New York audience to walk noisily out of the concert hall, show him at his most mordant. The prepared piano, its strings garnished with screws, bolts, and other assorted bits of metal, plastic, and wood, its overall effect surpassingly gentle and peace-evoking, was John Cage's most valuable invention of much greater interest, I think, than his later abdications of creative control in favor of aleatoric noise-making. The listed works by Milton Babbitt and Charles Wuorinen are probably not classifiable as avant-garde in any real sense. They are both superbly skillful and, yes, beautiful vindications of the continuing validity of this traditional medium. In comparison, the final entry by the thirty-seven-year-old George Crumb is avant-garde in every sense.

In Ancient Voices of Children, as in another of his best works, Echoes of Time and the River (recorded by the Louisville Orchestra under Jorge Mester on Louisville S 711), there is a tire some surrounding apparatus of mystical and numerological abracadabra. It does the music little harm; and if, rather as with Messiaen, you can either swallow it or ignore it, the rewards available from Crumb's tortuous, febrile imagination and exquisite ear are substantial.

Bernard Jacobson, an Englishman born and bred, was for a time music critic of the Chicago Daily News and Contributing Editor of STEREO REVIEW. He now lives in England but still keeps tabs on American music.

Also see:

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)