SPRING; "For me, for now, the ultimate reading of Vivaldi's Seasons";

AUTUMN; WINTER

HOWEVER much it is overplayed and over-recorded, Vivaldi's Seasons will always delight an audience and challenge a performer. The cycle is, after all, a masterpiece unique in the repertoire, certified by a deserved and unquestioned popularity, and it will therefore continue to remain fresh in good performances. Conductor Trevor Pinnock has turned in such a performance in a new release on the CRD label, a superb account from every point of view.

The most striking feature here is the use of low-pitch instruments, originals from the eighteenth century or copies of them. Although the sound might at first seem somewhat flat and colorless compared with some of the whiz-bang treatments the work has suffered on disc in the past, one soon grows accustomed to it and begins gradually to realize how marvelously subtle and delicate Vivaldi's string writing is. This, in turn, brings out the finer programmatic qualities of a work which, when per formed on modern instruments, often seems rather crude and even naive.

This is apparent from the very first "bird" solo of the "Spring" section, and it is consistently demonstrated right through to the frenzied tumult of the final storm of "Winter." Never have I heard so convincing a reading of the "fountain" passage in "Spring," or such delicate sounds as those produced by the "zephyrs" in "Summer." And, for the first time, the faithful dog in "Spring" stands out from the suave violin cantilena and the murmuring breezes.

Ensembles of old instruments frequently sound as if they were hampered by instrumental limitations they either just barely get the notes out, or one senses that they are frustrated in not being able to express themselves as fully as they could on modern instruments. Not so with the English Consort: not only are they technically perfect, but they bring out the full expressive capability of their instruments as well. They are aided in this by Mr. Pinnock's carefully wrought interpretation: the conductor scrupulously observes all of Vivaldi's original dynamic markings, but he is not afraid to use effective crescendos

and diminuendos (as well as the traditionally accepted terrace dynamics of the period) where a more modern sensibility indicates. Nor is he afraid of tempo changes. (No drunkard keeps a steady tempo, let alone running game but both are "characters" to be dealt with in the tale of The Seasons.) Such tempo changes, although effective for programmatic purposes, can upset the balance of a Baroque movement in which tempo is an important factor in maintaining a single "affection," but Mr. Pinnock seems to be able to accommodate variations in tempo and still maintain the thrust of the movement as a whole.

Violinist Simon Standage is as much at home in the Baroque as conductor Pinnock. He presents the concertos as the brilliant virtuoso pieces they are, indulging so successfully in some fine ornamentation of the slow movements that one wishes he had done more of it.

What he does do, however, is far from formulaic; it gives us a more than fair notion of what Vivaldi's bare melodic lines could-and doubtless were turned into in his time.

In short, this is for me, for now, the ultimate reading of The Seasons. Both the sonorities of the old instruments and the interpretation bring new light to the work, making it well worth adding to one's record library even though it may already be "well-seasoned."

-Stoddard Lincoln

VIVALDI: The Seasons. Simon Standage (violin); English Consort, Trevor Pinnock cond. CRD 1025 $7.98 (from HNH Distributors, P.O. Box 222, Evanston, Ill. 60204).

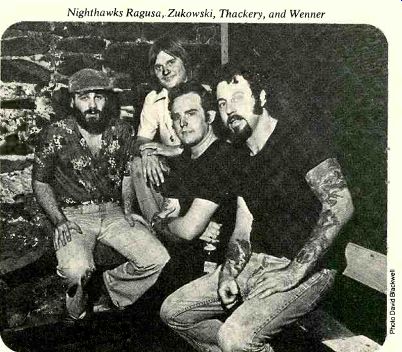

The Nighthawks: There's More To the Blues Than the Form

THE Nighthawks are a pugnacious and delightful combo who make love to rock and blues rather than trying to wrestle them to the ground.

Where most combos and bands assume they are dealing with the rich content of the blues by dealing with its limited form, the Nighthawks score because they reverse the process. The blues, like a coconut, is hairy and hard on the outside, but the meat inside is mighty sweet, and the Nighthawks know how to get at it.

Mark Wenner's harmonica and Jim Thackery's guitar are instruments of pure delight. Wenner's understanding and use of the harmonica, though grounded in urban blues, takes the instrument beyond its traditional roles in blues and folk; he has a fine romantic streak in him, and an independence of thought in solo ideas and construction of choruses. Thackery's hot and steamy solos are economic and exciting; he plays what is right to play, with occasional decoration, but he avoids the bluster-and-fast-finger syndrome that makes so many rock and blues guitarists annoying and wasteful.

The three wildest cuts on this live al bum are Shake and Fingerpop, Nineteen Years Old, and an all-stops-out

Shake Your Moneymaker. The audience yells, stomps, whistles, and presumably shakes its moneymakers.

They've got a right to: the Nighthawks are all right and mighty tight.

-Joel Vance

THE NIGHTHAWKS: Nighthawks Live. Mark Wenner (harmonica, vocals); Jim Thackery (guitar, vocals); Jan Zukowski (bass, vocals); Pete Ragusa (drums). Jailhouse Rock; Hound Dog; Can't Get Next to You; Shake and Fingerpop; Whammer Jammer; Tripe Face Boogie; Nineteen Years Old; Shake Your Moneymaker. ADELPHI AD 4410 $6.95.

------- Nighthawks Ragusa, Zukowski, Thackery, and Wenner

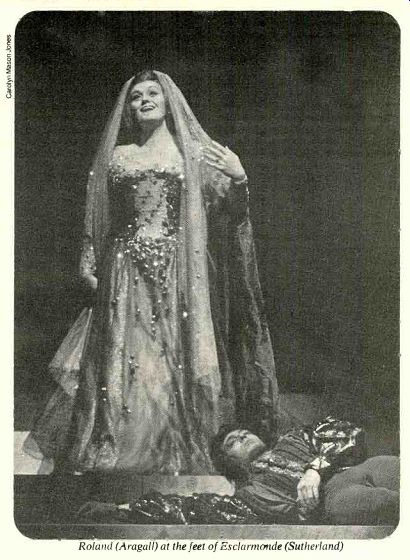

Jules Massenet's Esclarmonde: The French Understand These Things . . .

COMPLETED in 1888 at the peak of Jules Massenet's creative inspiration (between Manon, 1884, and Wer ther, 1892), Esclarrnonde was written for Sybil Sanderson, an American soprano of captivating beauty and remarkable vocal endowments. The op era enjoyed great success for a while but failed to enter the international repertoire; after 1934 it seems to have disappeared from the stages of France and Belgium as well.

The team of Joan Sutherland and Richard Bonynge is responsible for the opera's return to currency in a sweep that began with a San Francisco revival (October 1974), continued with the re cording I am about to discuss (London, July 1975), and led to a Metropolitan Opera production (November 1976), all three built around the same principals and an almost unchanging cast.

Though Esclarmonde is strongly indebted to Wagner, this influence should not be overemphasized. For one thing, Massenet's orchestration, for all its fleeting Wagnerian touches, is characteristically French in sound and transparency. Furthermore, Massenet no more abandoned the conventional arias and ensembles in this opera than he did in Manon and Thais, nor did he surrender to Wagnerian overstatement: his expression is concise, elegantly pro portioned, and (so far as the murky and involved story makes possible) reason ably clear.

According to one Massenet biographer, Esclarmonde is a "bewilderingly eclectic" opera. It is eclectic, without a doubt, but one is amused rather than bewildered on encountering, as the story unfolds, reminders of Armide, Ii Trovatore, Les Troyens , Lohengrin, Die Walkiire, Parsifal, Tristan and Isolde, and even anticipations of Turandot. The libretto by Alfred Blau and Louis de Gramont contains dashes of all these seasonings added to a knightly tale about the Byzantine princess Esclarmonde, a dabbler in the magical arts who becomes infatuated with and eventually seduces the Chevalier Roland-whose heroism, suffering, and ultimate triumph are also described.

That magical French mixture of religion and eroticism that lies at the core of so many successful operas (Manon, Herodiade, Samson et Dalila, and others) works well in this instance too. Massenet's music, sensuous and at times richly evocative of medieval mysteries, fits the poetic text elegantly, and the opera's rescue from oblivion is eminently justified for these reasons as well as for the quality of the recorded performance.

The elusive and mysterious character of Esclarmonde is a good choice for Joan Sutherland, whose singing style is usually rendered somewhat mystical by cloudy enunciation anyway. It is a demanding role calling for extended lyric passages a la Manon alternating with the sort of dizzying ascents and high staccatos we usually associate with Mozart's Queen of the Night. Miss Sutherland sensibly ignores the high F and G in alt the music actually calls for, settling for a number of high D's delivered clearly and firmly. In all, her voice is in admirable shape, pure and full bodied, and her technique is as good as ever.

Giacomo Aragall's part is less demandingly written, most of it lying in the tenor's attractive and effective up per mid-range, but the higher demands, when they do occur, are also met with a free and ringing top. Except for an awkward passage in the Epilogue, where the tessitura lies in the register "break," he sounds youthful and heroic, as the role requires, and sings with intelligence and sensitivity. The supporting cast is also good: Louis Quilico is strong and secure as the fanatical Bishop, Clifford Grant is sonorous in his solemn pronouncements, and Huguette Tourangeau supports her fine singing with exemplary enunciation.

Richard Bonynge must know this music better than anyone living. His leadership is justly paced, sensitive, and considerate of the singers' needs so considerate, in fact, that some of the composer's forte markings seem to have been sacrificed to this concern, though without any major detriment to the overall effort. Where the performance falls somewhat short is in the area Roland (Aragall) at the feet of Esclarmande (Sutherland) of precision and incisiveness; choral tone and accuracy, in particular, are not always what they should be. Technically, the sound is satisfactory if in no way exceptional.

Works plucked from opera's capacious oubliette seldom prove to be transcendental masterpieces, and Esclarmonde is no exception. But it is viable, colorful, and enjoyable, with a marvelous second act in which Scene I ends with a Tristanesque Liebesnacht followed by a Scene II that is all morning-after languor. The French under stand these things. . . .

-George Jellinek

MASSENET: Esclarmonde. Joan Sutherland (soprano), Esclarmonde; Giacomo Aragall (tenor), Roland; Clifford Grant (bass), the Emperor Phorcas; Louis Quilico (baritone), the Bishop of Blois; Huguette Tourangeau (mezzo-soprano), Parseis; Ryland Davies (tenor), Eneas; Robert Lloyd (bass), Cleo mer; others. John Aildis Choir and National Philharmonic Orchestra, Richard Bonynge cond. LONDON OSA 13118 three discs, $20.94.

Ry Cooder's "Chicken Skin Music" Revitalaes Some Still Lively Roots

HAVING chosen to make himself a dynamic in the folk process, Ry Cooder keeps tracking our music back to its roots and showing us that the little devils are still alive. He plays source music with respect and understanding, but he also plays it his own way. In "Chicken Skin Music" for Reprise he mixes Tex-Mex instrumentation with white-country and Leadbelly songs, Hawaiian styles with such manufactured pieces as Yellow Roses and Chloe (Chloe! He does it as an instrumental the words would be just too dang Spike Jones much-but bringing it up in the first place is a typically sly Cooder stroke), and gospel with various seemingly incongruous elements, and it all

--- MELOS QUARTET OF STUTTGART: Wilhelm Melcher, first violin; Gerhard Voss,

second violin; Hermann Voss, viola; and Peter Buck, cello comes out with its

flavor not only intact but spiced up like you just wouldn't believe.

All this music-just about all of Cooder's chosen music-is from poor people. Spiritually, therefore, it doesn't want to be dressed up lavishly or expensively but colorfully, the way that Staggerlee-type character in I Got Mine would dress. Cooder understands this perfectly. He never plays fancy licks for their own sake and he never seems to bend his vision for the sake of selling a few more records. "Chicken Skin Music" has a jagged, free-for-all sound that deepens your impression of what life must have been like for the people behind the music.

Cooder's singing, which seemed to reach nearly its full maturity about one album back, is sure and sympathetic, but it has its own integrity. The songs, like their sources, represent a variety of styles and approaches (this album is, in a quiet way, wildly experimental) but they're all going to the same place. One experiment-putting a bolero beat and Flaco Jimenez's slightly overplayed diatonic accordion to He'll Have to Go, an old country song popularized by Jim Reeves-comes off only half-baked; he needed to live with that idea a little longer. But less likely-appearing experiments have worked out beautifully, and in all Cooder makes quite a coherent and detailed statement about him self. You may find yourself mentally underlining long passages of it.

-Noel Coppage

RY COODER: Chicken Skin Music. Ry Cooder (vocals, guitar, mandolin, mandola, bajo sexto, accordion); Milt Holland (per cussion);Chris Ethridge (bass); Gabby Pahi nui (Hawaiian steel guitar); Atta Isaacs (guitar); Flaco Jimenez (accordion); other musicians. The Bourgeois Blues: I Got Mine; Always Lift Him Up; He'll Have to Go; Smack Dab in the Middle; Stand by Me;

Yellow Roses; Chloe; Goodnight Irene. RE PRISE MS 2254 $6.98, M8-2254 $7.98, M5-2254 $7.98.

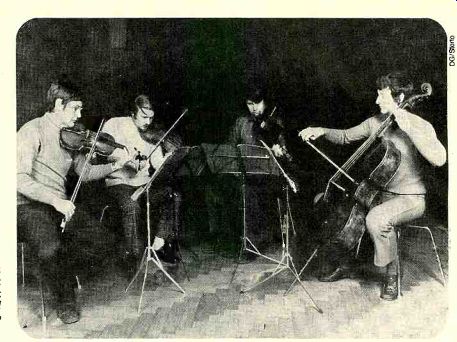

Formal Integrity and Astonishing Substance In Luigi Cherubini's Six String Quartets LUIGI CHERUBINI, productive to the end of his long life (1760-1842), was a working contemporary of Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Weber, Mendelssohn, and Schumann.

In his own time he was regarded as highly as they; Beethoven himself spoke of him as the greatest of his con temporaries. Cherubini is remembered today for but a handful of works Medea, the two Requiems, the Sym phony in D Major, and perhaps the Overture to Anacreon. The idea of associating his name with chamber music is one that would never occur to most of us, and for that reason alone the Deutsche Grammophon Archiv set of his six string quartets is an intriguing release. One might have thought one or two of these works would have been an adequate sampling, but after hearing the splendid performances by the Melos Quartet of Stuttgart one is inclined to replace the word "intriguing" with "important." The quartets, all mature works, are fascinating for the influences suggested here and there (not always supportably), but still more for their formal integrity and frequently astonishing sub stance. For example: No. 1, in E-flat, composed in 1814, is notable for a remarkable scherzo whose main section echoes the particular Spanish style identified with Boccherini and whose trio even more sharply "pre-echoes" Mendelssohn. And No. 2, in C, is immediately recognizable as the same music as the aforementioned Symphony in D; Cherubini adapted the orchestral work of 1815 some fourteen years later, replacing the original slow movement with a Lento whose greater depth and expressiveness are more effective in the chamber-music context.

The first two quartets were separated by fifteen years, the second and third by five, but then Cherubini went on to produce a quartet each year from 1834 through 1837. Each of these final four is, to a greater or lesser degree, striking for its parallels with the style of Beethoven in his late quartets-works with which, as Ludwig Finscher observes in his annotation, "Cherubini was probably unfamiliar." There is, in any event, no suggestion of imitation, but simply of resemblance; the style seems as natural and uncontrived on Cherubini's part as on Beethoven's. Quartet No. 4, in E Major, is a masterwork by any measure: the theatrical echoes one ...

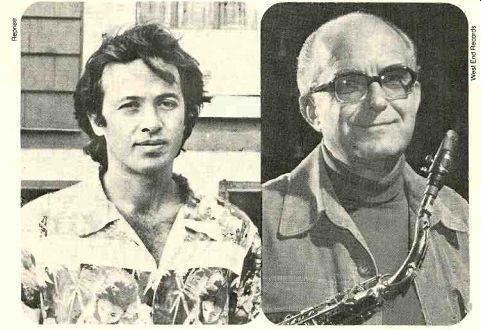

------- left, Ry Cooder: a dynamic in the folk process; right,

Fraser MacPherson: fluid, full-bodied tenor sax

...might have heard (or imagined) in the earlier works are entirely absent now, and in their place is a dramatic tension achievable only in the most intense and intimate chamber works. That tension is enhanced here by a subtle scheme of thematic relationships and a wholly original finale in which the drama is deepened rather than resolved. The Fifth Quartet, in F, reverts in part to the more ingratiating style of the earlier works, with the Rasumovsky set rather than the later Beethoven works as possible models (Finscher considers the finale of Beethoven's Op. 59, No. 3, the "definite source of inspiration" for this work's finale). The Sixth, in A Mi nor, is again different; it is cooler and more serene than its predecessors, yet not without drama-a conscious summing-up, it would seem (as it does to Finscher), of Cherubini's entire creative life as he worked through the second half of his eighth decade.

The performances are communicative in the best sense, exuding an air of real affection and deep commitment.

The recorded sound is near-perfect in its clarity and balance, and in the accompanying booklet Finscher's in valuable notes are augmented by an essay by Wilhelm Melcher (leader of the Melos Quartet) on the sources and interpretation of the quartets, with sever al musical examples. This music is a good deal more than a "novelty," as anyone already acquainted with the quartets of Beethoven, Schubert, et al. will delight in discovering.

-Richard Freed

CHERUBINI: String Quartets: No. 1, in Ella Major; No. 2, in C Major; No. 3, in D Mi nor; No. 4, in E Major; No. 5, in F Major; No. 6, in A Minor. Melos Quartet of Stuttgart.

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON ARCHIV 2723 044 three discs $23.94.

At the Planetarium in Vancouver, B. C.: Fraser MacPherson's Good, Live Jazz IF you live in the Vancouver, B.C., I area, chances are you've heard the music of Fraser MacPherson, Oliver Gannon, and Wyatt Ruther. If not and if you like your jazz served ever so mellow and swinging-I strongly suggest that you track these men down and catch their next appearance. At this point I should confess that I had never heard of MacPherson, Gannon, and Ruther until I received for review an al bum on the West End label, so I really don't know if they play together regularly. Judging by the rapport in evidence on the record, however, I'm quite willing right now to lay a little money on it.

The album-a consolation to those of us who are at a geographical disadvantage-captures MacPherson and his colleagues in concert at Vancouver's MacMillan Planetarium on an inspired Monday evening in December of 1975.

Fraser MacPherson's tenor style is Getz-based, he plays with the fluidity and, occasionally, the phrasing-of Lester Young, and he has the full-bodied tone of Don Byas. Like Charlie Christian, Oliver Gannon plays an amplified guitar, which-unlike the electric guitar-retains some of the tonal qualities of its Spanish ancestor.

His touch is delicate, his technique is flawless, and he has the soulfulness of Django Reinhardt-an obvious influence. Not surprisingly, then, Gannon sollos extensively on Django, John Lewis' hauntingly beautiful tribute to the late Belgian guitarist. It is a tune that suffers not at all from being lovingly nudged along by MacPherson's tenor, and throughout the album Wyatt Ruther's acoustic bass is the perfect complement.

The three players don't break any new ground, but they plant a little new life in the old, and they do it so tastefully and with such obvious love that you simply have to be moved. The album appears to be a private release, the kind that usually ends up in somebody's basement, stacked up in cartons and collecting dust for want of proper distribution and promotion, but if that happens to "Fraser-Live at the Planetarium" there is simply no justice.

-Chris Albertson

FRASER MACPHERSON: Fraser-Live at the Planetarium. Fraser MacPherson (tenor saxophone); Oliver Gannon (guitar); Wyatt Ruther (bass). I'm Getting Sentimental Over You; Li'lDarlin'; Lush Life; My Funny Val entine; Tangerine; Django; I Cried for You.

WEST END 101. $7.95 (from Record Search, 1294 Gladwin Drive, N. Vancouver, B.C., Canada).

------------

------

-----

Also see:

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)