FIEDLER OF BOSTON: A profile of the builder of America's musical bridges, by IRVING KOLODIN

FIEDLER---- BUILDER OF AMERICA'S MUSICAL BRIDGES

MR. FIEDLER, "said the voice of the telephone operator in the New York Hotel where the conductor was staying on a recent visit to the city, "is in the King Cole Room." No doubt, I thought as the call was being processed, with his pipe, his bowl, and his fiddlers three, preparing for a forthcoming bash in royal surroundings.

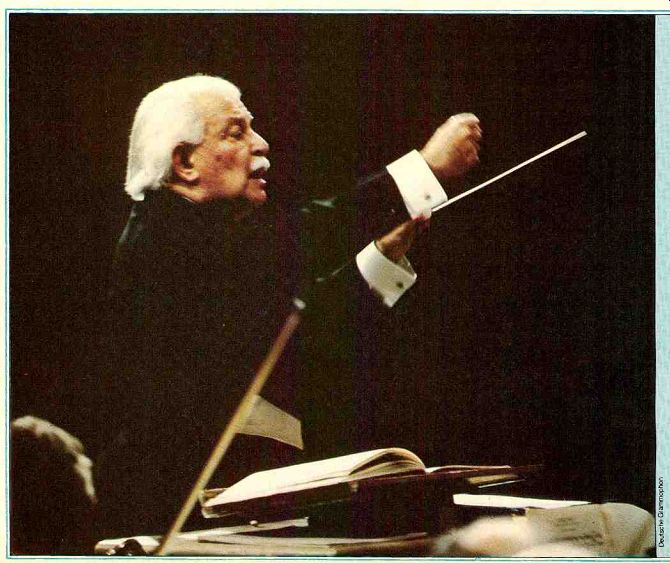

If the Nassau ( Long Island) Coliseum may be construed as "royal surroundings," then so it was-with the fiddlers three augmented by all the other strings, brass, and woodwinds that make up the Boston Pops Orchestra. By no coincidence at all, the concert was part of a week's sojourn during which the parent Boston Symphony paid its first visit of the season to New York. The players' time was divided between their Symphony commitments with the current music director Seiji Ozawa (two concerts :n Carnegie Hall), and the Pops with the perennial Fiedler (the Saturday program on Long Island followed by a TV taping on Sunday).

Photo courtesy Deutsche Grammophon

"Music was all around the first generation of Boston-born Fiedlers."

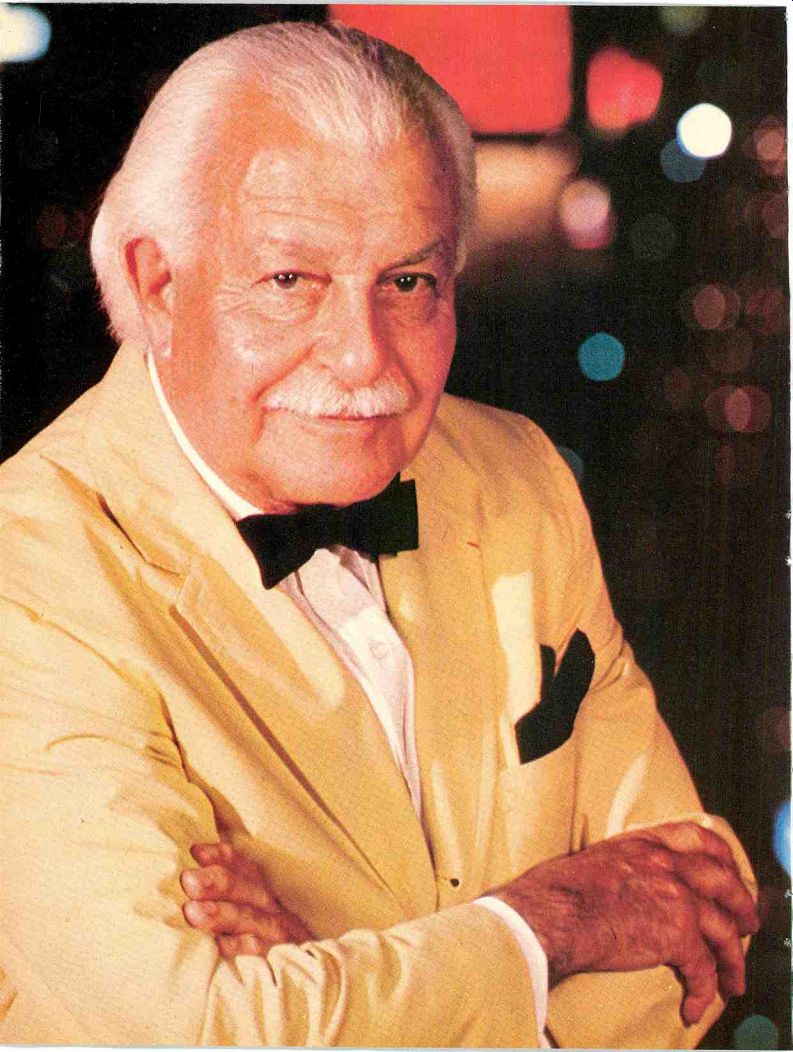

Such assignments have for so long been the pattern for the pink-cheeked, white-haired gentleman who has to be the liveliest octogenarian in the musical community that there are millions who think he has been doing nothing else all his life. And certainly among that group is the mass of individuals who have, collectively, bought more than fifty million records with Fiedler's name on them during the last forty eight years.

Scattered among those fifty million discs, most of which are by the Boston Pops, are a comparatively small number marketed in the name of the Arthur Fiedler Sinfonietta, an aggregation whose surpassing performances of works by Bach, Boyce, Corelli, Felton, Handel, Mozart, Pachelbel, Telemann, and even Hindemith conjure up the possibility of quite another career for the conductor. They amply prove that America has given birth to very few musicians equal to Arthur Fiedler in talent, training, and that very necessary extra ingredient we try to describe with the word "temperament."

The question on my mind, when Fiedler had settled down for the visit that followed the phone call, was: "Do you ever look back and think of another path that might have taken you in quite a different musical direction?" The answer came quickly enough to suggest that the thought had perhaps crossed his mind. "Well, you can't help thinking of that. But I am really very happy. I chose this way myself. I have been connected with the Boston Pops for forty-eight years and I am very glad to have had the opportunity. I like the diversity of the repertoire. I am not a specialist in anything, as some people are in Mahler, or Bruckner, or what not. I like to do all types of music.

All Pops concerts, you know, are divided into three parts. The first section is rather good music. The second part is a soloist. The third consists of light mu sic of various kinds-show music and music of the day." "The question comes up," I elaborated, "among some of us who, being familiar with your varied-I don't say checkered [small chuckle from Fiedler]-career in all its aspects, have long thought that your gifts were of a nature that, had you concentrated, could have led almost anywhere." "Well, yes," ...

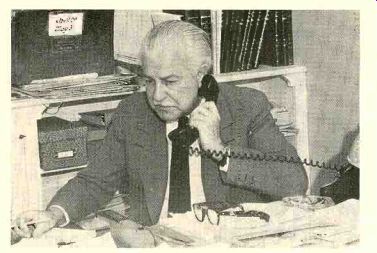

------- There's more to it than just waving a stick; Fiedler spends more

time at his desk than on the podium.

.... agreed Fiedler, "had I concentrated. I know, as an instance, when I began to conduct the Pops concerts in the Thirties and even before, that people approached me to take over this and that orchestra in smaller communities in the United States. Well, that would have gotten me involved in local politics, which I don't like, and I wouldn't have had the kind of orchestra I have in Boston-it was a great temptation to hang on to that. Furthermore, the whole idea of the Pops concerts needed someone really to give his whole devotion, time, and love to it. I don't care what I play, I try to do it all damned well. In any case," he added with a laugh, "it's too late to change now. After all, I have performed with almost every orchestra you can mention in America. Only last week I conducted the Chicago Symphony, which is, as you know, a great orchestra." The mutually accepted, if unspoken, point of it all was that, under the light touch and even the frivolity that some times invades his Boston Pops work, there is the hand of a master musician and the mind of a man cultivated by long association with some of the greatest artists of his time. And the prime condition of the Boston Pops indeed shows the devotion, time, and love that Fiedler has lavished upon it.

THERE was another Fiedler in the 1 Boston Symphony when the Pops were born in 1885. That Fiedler was the Vienna-born Emanuel, father of Arthur, who had been recruited for ser vice in America by his friend Wilhelm Gericke, an honored name among the orchestra's early conductors. Pops concerts were then directed by Adolf Neundorf in the old Boston Music Hall on behalf of city-bound Bostonians who couldn't escape the summer doldrums by running off to Cape Cod or the White Mountains. They sat at tables, perhaps with an ice for refreshment, and responded to performances of Rossini's William Tell Overture and Strauss' Pizzicato Polka very much as their fourth-generation descendants do today.

In addition to Father Fiedler, there were brothers Gus and Benny in the violin sections, and they were eventually joined by a cello-playing relative whose family name (Zimbler, later associated with a Sinfonietta he organized) concealed an offspring of Emanuel Fiedler's sister. Music was therefore all around the first generation of Boston-born Fiedlers, which included Elsa, a fine pianist, and Rosa, a cellist, as well as Arthur. This was only as natural as the family name they had inherited.

------------------

The View From Boston

FIRE departments and universities across the land have honored Arthur Fiedler, but in the serious music community he has apologists. "The Pops are all very well," the condescending defenders will say, "because they help to subsidize the more significant activities of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Fiedler gives young artists their first opportunities to play as soloists with orchestras. And who knows how many people have been brought to appreciate greater music be cause they were introduced to it when they came to hear Arthur Fiedler con duct something else?" The apologists are saying true things, but they are not emphasizing the right ones. The Maestro himself, for example, doesn't think his job is to toil as a musical missionary among the quality-deaf heathen. "I just want people to have a good time," he will say, going on to quote Rossini's famous re mark about how all kinds of music are good except the boring kind.

It has been Fiedler's great gift to the public that so few kinds of music are boring to him. In addition to the arrangements of current hits that turn his orchestra into the world's classiest jukebox, Fiedler has over the years conducted most of the standard repertoire, made significant incursions into areas of music that have since become standard thanks in part to his advocacy, and kept alive a whole tradition of honorable music that is both well made and entertaining.

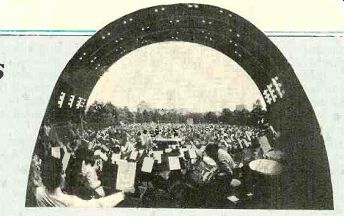

And, of course, no music in a Fiedler performance ever seems boring thanks to his taste in arrangers, his pro gram-building abilities, his skill on the podium, his joy-communicating personality; Fiedler makes music reach people. On the Fourth of July this last year a crowd of more than 400,000 people gathered on the banks of the Charles River to hear Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops Orchestra. That crowd was about the same size as the one at Woodstock; combined with the television and radio audience it may have been the largest public ever assembled to hear a symphony orchestra.

There were extra-musical reasons for that: there was a gaudy fireworks display to spangle the sky; the beautiful night invited picnicking and confidences; and it was, after all, the actual Bicentennial of our nation's birth. But the cheer that went up after every se lection on the program reaffirmed the place music has in all the most important public and private moments of our lives as it reaffirmed Arthur Fiedler's long, loving, and lasting association with festivity.

Richard Dyer

Music Critic, Boston Globe

---------------------

"It's really not the money that keeps me going, it's the activity. But

I have slowed down...."

"After all," the conductor observed, "as a tailor came by the name of Schneider in the old country, and a cobbler was a Schumacher, so we fiddlers became Fiedlers." With violin studies in Berlin behind him, and a diploma from that city's Hochschule in his pocket, where else should the young Fiedler go but back to Boston (especially in 1915, with Europe locked in World War I,? No reception committee with offers in hand awaited him at the pier; he spent a summer playing at a resort on Nantucket before an opening occurred in the second violin section of The Symphony (there has been, traditionally, only one symphony as far as Bostonians are concerned).

"I have never had another job than the Boston Symphony," confided Fiedler. "I started with Karl Muck, as you know. It was a different world in those days. No guest conductors; one man did the whole damned thing. No time off to guest conduct elsewhere. It was severe, but it was rewarding." Asked if he could capsulize his recollections of Muck (who made the Boston Symphony's first recording ever, in 1917, with fiddler Fiedler playing in the finale of Tchaikovsky's Fourth Symphony as well as other selections), he replied:

"He was a very educated man. He had a Ph.D. . . . legally, not honorarily.

He loved mathematics, as many musicians have. A very precise man. Never sentimental-something I hate in mu sic-and very productive in his use of rehearsal time. Knew what he wanted.

Highly industrious. Would take home parts that needed treatment, like the woodwinds, and put in markings always in very good taste-in his own immaculate hand." DOUBTLESS Fiedler could furnish a similar word picture for every subsequent Boston Symphony conductor and music director. He played under three others--Henri Rabaud, Pierre Monteux, and Serge Koussevitzky-as well as being proconsul (for Brookline) for every music director since Koussevitzky: Charles Munch, Erich Leinsdorf, William Steinberg, and, now, Ozawa. "You know," said Fiedler, "we venerated the conductor in Muck's day. Doffed our hats if we met him on the street or backstage. The other day, as I was leaving Carnegie, a young member of the Pops came charging by. 'Hi, Arthur!' he yelled at me.

Damned if I even know his name. Imagine what would have happened in the days of Muck or Koussevitzky." The impulse to conduct began to stir in Fiedler as he approached his tenth year in the orchestra. In 1924 he organized a group of colleagues into the Fiedler Sinfonietta; the aggregation persisted and came in time to record, with E. Power Biggs, some of the first Handel organ concertos ever available in this country. Sitting on the banks of the Charles a few years later, Fiedler visualized an activity that would give additional employment to himself and members of the orchestra while providing Bostonians with free outdoor music of high quality. The Esplanade Concerts were born in 1929, and among the other things to which they gave rise was Fiedler's career as conductor of the Boston Pops. The Sinfonietta and the Esplanade Concerts demonstrated his rapport with his colleagues, his businesslike way of getting things done, and these were factors in his favor even if being born in Boston was not. In looking for a new conductor for the Pops, continentalists among the orchestra's directors had thought an Italian-Alfredo Casella, for example could take the pulse of the public bet ter. That experiment ended after a sea son or two; Fiedler got the job in 1930.

However, it was not until the mid-Six ties that Fiedler became the first Bos ton-born musician to conduct the Sym phony in a subscription concert.

Once given his chance with the Pops, Fiedler did what every productive per son does with such an opportunity: he converted the orchestral programming into a mirror image of himself. If there is a Beethoven overture on a Pops pro gram, it is because Fiedler, in the days of recorded versions by Toscanini and Weingartner, did a better-sounding Weihe des Houses than either. And if the audience responds to a special kind of character in Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 1, it could be for the reason I gave in a comment of mine on Fiedler's recording of it (c. 1940):

"There is a suspicion of the Nikisch treatment in the vigorous grandeur of the first side." Over the years, new names and new pieces have taken their places in the Boston Pops repertoire because Fiedler is a man devoted to both.

As an instance, I asked him how Leroy Anderson came into his life. "Leroy Anderson?" cross-queried Fiedler.

"He was a young man at Harvard Mu sic School when I first got to know him, studying and leading the Harvard band.

Very scholarly. I asked him to do a few arrangements for us. In return he asked to be allowed to attend Pops rehearsals, something we never permitted. I agreed, and he came regularly every day, listening very attentively, with razor-sharp ears, learning everything about instrumentation. He came in one day, looking very sheepish, and said: 'I have here a little piece I have written.

Look at it and tell me what you think.' I looked at it. It was called Jazz Pizzicato. I liked it, and we played it. Very cute. People loved it, and we arranged to record it. As it was quite short, I suggested he write another piece to pre cede it. That was Jazz Legato. Every thing went on from there: Syncopated Clock, Toy Trumpet, Sleigh Ride, all charming, with wonderful titles that framed the music he wrote. He also did excellent show arrangements for us Kiss Me Kate, things like that." Not all such stories have happy endings, of course. Like the one that be gins with Fiedler's discovery, while leafing through stacks of music in a New York publishing house, of a piece called Jalousie. The composer's name was Jakob (not Niels, of nineteenth century fame) Gade, and Jalousie was to become the first Pops record to sell a million copies. Several years after this memorable success, the phone rang in Fiedler's Boston apartment. "Here is Jakob Gade," said the caller. "You have done so much for my Jalousie. I came from Copenhagen to thank you." There was little Fiedler could do but invite the man up. When the doorbell rang he discovered a small, quaintly dressed, middle-aged figure with a package under his arm. "Here is my symphony," said Gade, presenting the bundle. Years later, Fiedler remembers it as "one of the worst pieces of music I ever looked at."

YEARS of evolution have brought changes of matter rather than of manner to Fiedler's work. Did he wear a wig to dramatize his presentation of the Beatles' music in the Sixties? Yes, he did. And in 1936 he had taken pride in welcoming his father, on his seventy-second birthday, as a playing member of the Esplanade Orchestra in a performance of Brahms' C Minor Sym phony. A doting son? Of course. But a news-minded showman as well, as a contemporary picture of the event in the Boston Traveler attests. Some of us wince just a little when a Fiedler an tic-a bewhiskered Santa Claus at Christmas time, for example-is caught not only by local news cameras but by the vastly more public ones of TV. but the publicity is effective.

Asked to define his own attitude to ward the present-day Pops repertoire, Fiedler, in effect, echoed the maxim attributed to the great Theodore Thomas in the 1890's when he was creating America's symphony-orchestra audience: "Popular music is familiar mu sic." Says Fiedler: "I continually add to the catalog music from current shows, music from movies, music people enjoy dancing to and might enjoy hearing in arrangements for our great orchestra-all as a supplement to the old favorites. Right now we are doing A Fifth of Beethoven, a hit record created by a man named Murphy. Very cute. Some people might call it immor7 al. I think it's fun. You know, there should be fun in music. All the great composers wrote music for fun-

---------------------

Arthur Fiedler -- Latest Discs

...no reservations about the stunning performances or demonstration-quality sound"

IT is good to find Arthur Fiedler re cording real music again after the long stretch of show tunes, rock med leys, etc. Polydor had him doing. His expert handling of the Moussorgsky, Saint-Saens, and Dukas staples on a new DG disc reminds us that he is, after all, the conductor whose 78-rpm re cording of Beethoven's Consecration of the House Overture received almost universal critical acclaim, and who gave us so many "reference" versions of dozens of other concert works by Weber, Rossini, the Strauss family, Wolf-Ferrari, Ibert, Dvorak, Paderewski, MacDowell, et al. (to say nothing of those "Mottled" goodies by Rameau. Gluck, and Leclair). I suspect most listeners will want, and perhaps already own, more of the three ballets than the single excerpt by which each is represented on the DG recording (certainly so in the case of the Stravinsky), and at this price one does try to avoid duplications. I have no reservations at all, though, about the stunning performances or the demonstration-quality sound.

One of those ballet pieces is in fact duplicated in the bargain-price assortment-a kind of Basic Library of Fiedler-assembled by RCA from recordings made between 1956 and 1967.

And, if it matters, I like both the performance and the sonic treatment of the Sabre Dance just a little bit more in RCA's 1958 version, for the remastered sound is remarkably undated, with everything shimmeringly realistic and well focused. Fiedler was, I think, the first to record Wein, Weib and Gesang with its wonderful introduction uncut, and his 1966 remake is a classic demonstration of the style he acquired as a teenage member of the great Strauss-family orchestra itself.

View from the inside out: the Boston Pops Esplanade concert July 4, 1976.

(Photo: R. Di Natale/Seagull Corp.)

John Green's fussy arrangement of Strike Up the Band is less appealing than the one Fiedler recorded some forty years ago, but the stylish presentations of Jalousie and the Fire Dance parallel those that made that same coupling the famed best-seller it was in Victor's 78-rpm Red Seal catalog for a decade or so. What a knowing, subtle, and altogether untired Waltz of the Flowers, and what an equally subtle blend of gutsiness and dignity in the Sousa!

PERSONALLY, I'd have preferred a Nicolai or Suppe overture in place of the pop numbers, but the point of this particular collection, obviously, is to il lustrate the elegance and panache this rather extraordinary figure has brought to all his music-making when he's been at his best-and that has been in a greater percentage of his undertakings than anyone could reasonably ask, from any musician active in so varied a repertoire over so long a period. A great showcase.-Richard Freed

ARTHUR FIEDLER: Danse Infernal.

Moussorgsky (arr. Rimsky-Korsakov): Night on Bald Mountain. Saint-Satins:

Danse Macabre, Op. 40. Khachaturian: Gayne: Sabre Dance. Dukas: The Sorcerer's Apprentice. Stravinsky: The Firebird: Infernal Dance of Kaschei.

Ginastera: Estancia: Malumbo. Boston Pops Orchestra, Arthur Fiedler cond.

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2584 004 $7.98.

ARTHUR FIEDLER: A Legendary Performer. Gershwin (arr. Green): Strike Up the Band. J. Gade: Jalousie (Tango Tzigane).

Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker, Op. 71a: Waltz of the Flowers. Falla: El Amor Brujo: Ritual Dance of Fire. Ippolitov-Ivanov: Caucasian Sketches, Op. 10: Procession of the Sardur. Mascagni: Cavalleria Rusticana: Intermezzo. Khachaturian: Gayne: Sabre Dance.

Johann Strauss II: Wine, Woman and Song, Op. 333.

F. Loewe (arr. Hayman): My Fair Lady: Selections. Lennon-McCartney (arr. Hayman): I Want to Hold Your Hand. Raye-Prince (arr. Hayman): The Boogie-Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B. Sousa: The Stars and Stripes Forever. Boston Pops Orchestra, Arthur Fiedler cond. RCA CRLI-2064 $7.98.

-------------------

Mozart, Haydn, Schubert. I also like to think of myself-some people, again, may dislike me for saying so-some what as a chef. I try to make a good combination of elements, beginning with an hors d'oeuvre, then a main course, and, of course, dessert-don't forget dessert. People love it. I like to think that we play not only things that are popular, but those that have the potential to become popular." Fiedler's relish for his own identity is not difficult to understand. He likes to be liked, of that there is no doubt. He enjoys living well, and that has its price. Young musicians have enjoyed his patronage on innumerable occasions, and that he enjoys too. The first time I heard Grace Bumbry was at a Pops concert conducted by Fiedler in the San Francisco Civic Auditorium in the early Sixties. "Right," he confirmed. "She was as nervous as a witch, but very curious, in an intelligent way, about everything connected with singing with an orchestra, that being her first time. She's gone a long way. So has Tedd Joselson, one of the more recent new pianists to play with me, and Horacio Gutierrez.

"It's really not the money that keeps me going," says Fiedler, "it's the activity. But I have slowed down from the year in which I had 197 dates-not including rehearsals or recordings. I like to travel, but it takes me away from home too much. My wife doesn't enjoy travel as much as I do; when she does, it's usually on a long (and expensive) trip-Hawaii, for example, where we'll be a week from now. Often on tours I run into colleagues. Recently I met up with Rubinstein. He said to me, 'Arthur, why do you travel so much?' I said to him, 'Arthur, why do you travel so much?' We both laughed. But if I didn't move around, especially if I had to give it up or--God forbid--retire, I think I'd just collapse. I really need the activity." AN abiding share of this activity, wherever Fiedler finds himself, is in firefighting, its lore and its techniques.

Pictures of him attired as a deputy chief, in a rubber coat and boots, are probably in more newspaper files than similar snaps of any prominent personality since the late Ed Wynn was selling gasoline for Texaco or Fiorello La Guardia was mayor of New York.

Fiedler drives a Volkswagen whose plates identify him as an honorary deputy chief of the Boston Fire Department, and it is radio-equipped to alert him to the outbreak of any major fire in the Boston area. While on tour, his ho tel telephone operator is instructed to flash his room any time a four-alarm fire is reported.

Asked to explain this phenomenon, Fiedler offered as concise an explanation as his capsule comment on Muck as a conductor. "When I was growing up, I liked to play ball with the kids, but I spent most of my time practicing and couldn't get out. So, when I had a little time free, I'd go down the street to the nearby fire house, play with the dogs, pat the horses (they had horse-drawn trucks in those days), and make friends with the firemen. They were all nice fellows and let me slide down the pole from the room upstairs where they slept or played cards between calls.

Then the alarm would sound, and off they'd go. I was left alone, wondering what they did at the fire. As I grew up, they called me ' Sparks' (I later owned a Dalmatian called Sparks). I was what now would be called a buff. Do you know how that term came about? No? Well, in the old days, here in New York, when the engine went out on trips in the winter, they'd be followed by fellows wearing buffalo coats, which were then popular. When the men got to the fire, one would say to the other, 'Look at the buffs."' "Sounds logical," I commented.

--- "I am an honorary chief in over three hundred fire departments all over the world." ---

"Right," said Fiedler. "But my interest in firefighting goes deeper than that. A very good friend of mine when I was growing up was a man named Codman, who became Fire Commissioner of Boston. Knowing of my interest, he gave me credentials which allow me to be on the scene where the deputy arrives and begins to organize the strategy for fighting that particular blaze. It varies all the time, depending on the wind, the kind of building, the materials, all kinds of factors. The chief on duty has to make up his mind quickly and outline the plan to be put into action. It's much like conducting an orchestra. You go out and go to work immediately. No time for second thoughts or changing a tempo. You have to go to the heart of the matter instantly." He thought for a moment, then remarked, "You probably wouldn't believe it, but I am an honorary chief in over three hundred fire departments all over the world." That includes not only Brookline, Massachusetts, and Tokyo, Japan, but Vienna, Virginia, the home of the Filene Center at Wolf Trap, where Fiedler conducts regularly. I would not be surprised to learn that it also applies to the firefighting arm in Vienna, Austria, if only to honor Fiedler's long association with such incendiary matter of lo cal origin as Josef Strauss' Feuerfest.

Despite his imposing credentials as the only person remotely connected with classical music who has ac cumulated a sales total of over fifty mil lion records, it will surprise most readers (it surprised me) to learn that, at this writing, neither Fiedler nor the Boston Pops has an ongoing recording affiliation. He deplores the situation, he says, more on behalf of the orchestra's personnel than for himself, because re cording fees have become an anticipated part of their annual income.

RECORD collectors will remember that RCA gave up its long association with the Boston Symphony and the Pops because of the heavy investment it had to make in the Philadelphia Orchestra. RCA wanted, apparently, to retain the Pops, but Deutsche Grammophon, the company that was to sign the Boston, wanted all or nothing.

Now, after five years with DG (on the Polydor label), the Boston Pops is free lancing. An affiliation with London's Phase IV produced some impressive records, but the bugaboo of high production costs makes it necessary to achieve astronomical sales in order to show a profit, the kind of sales that result from long association with a single label and consequent over-the-years promotion. So the future of both Fiedler and the Pops remains for the moment in doubt.

But whatever the vagaries of the remainder of his career, Arthur Fiedler's combination of musical distinction and vast popularity will be a tough act to follow. I have heard at least one American's name suggested as a possible Pops conductor if and when, but he'd better acquire a good many more humane attributes to go with his nice back and sprightly tempos if he wants to succeed in this line. They didn't name a span across the Charles River (beside the Esplanade) the Arthur Fiedler Bridge just because he went to a lot of fires. Arthur Fiedler has been building America's musical bridges all his public life.

Also see:

Stereo Review's GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING MUSIC

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)