BY RICK MITZ

At

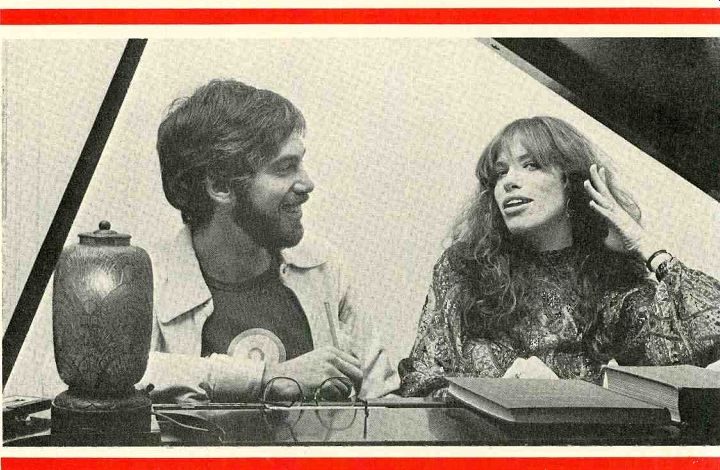

left, collaborators Jacob Bracktnan and Carly Simon. Photo by Ian Anderson.

ROCK AND-ROLL lyrics have come a long way. They began, perhaps, when the Beatles said they want ed to hold our hands. Now some of the more flamboyant rock groups are on record as wanting to hold other parts of our anatomies.

Rock lyrics have certainly gotten more suggestive with time-when the rock group Bread sings I Want to Make It with You, you can be sure they don't mean dinner. And at least some rock lyrics have gotten more grown up consider nearly any of the literate lyrics written by composers Joni Mitchell and Paul Simon. But today, with record sales reaching into the billions (dollars, that is, not discs), the prevailing style is formula, the most important ingredient is the hook, that unpredictable, un-definable something that pulls kids off the streets and into the record stores, and any rock lyricist who wants to make it with his bank book had better know the intricacies of both.

"Rock lyricist? Is there really such a person, someone who makes his living writing those words?" a young innocent recently asked me. "I thought they just-you know-made them up as they went along or they were written by the same people who write all those greeting cards. You mean there are people who actually sit around and think up those words to those songs?" Yes, there are, and they do. There is a new breed of professional rock lyricists-the "poets," if you like, of this generation-who don't perform in con cert, who don't make records, who are rarely heard even to hum. What rock lyricists do, simply, is write the words to rock music, but it is a whole lot less complicated to describe than to do.

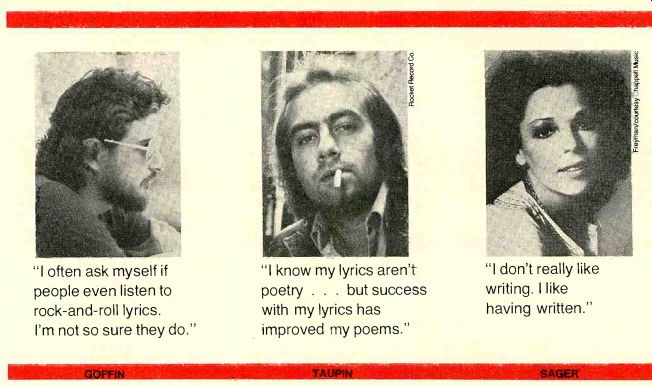

"The one thing you've got to remember," says one long-time music-biz ob server, "is that a person who writes rock words has to come up with hits, hits, and more hits. They have to be dependable, consistent, and contemporary; they have to know how to write what people will buy." One of the things people will buy is a song that is attached to lyrics by Gerry Goffin, the dean of American rock lyricists. As a long-time collaborator with music writer-singer Carole King (they collaborated in marriage for some time as well), Goffin has written half of such hits as Will You Love Me Tomorrow, The Loco-Motion, Up on the Roof, One Fine Day, A Natural Woman, and scores of others. A quiet man who ex presses himself better on paper than he does in person, Goffin now lives in California, where he continues the craft he learned and mastered in New York.

"I write lyrics," Goffin says by way of clarification. "I don't write poetry. Joni Mitchell writes poetry. What I do is write the simple lyric. Lyrics have less variety of image and use more conventional language. Lyrics involve get ting a hook phrase that people can hold on to. I consider it to be a craft, but it's not hack work. And I know it has its artistic limits."

When Goffin and King got together in the early Sixties, though, it seemed as if they knew no limits. In just five years they created more than a hundred commercially substantial singles and at least a hundred more that didn't make it. Goffin's lyrics, reflective of the mood of the times, dealt with teen problems and simple emotions. One of his best was Up on the Roof:

When this old world starts getting me down And people are just too much for me to take, I climb way up to the top of the stairs And all my cares just drift right into space.'

"I don't think my lyrics have improved any over the years," Goffin says. "I sort of like my old ones better.

They were written from the perspective of a younger person with a better, more optimistic outlook on life. My lyrics were happier then. Today, the things I write about apply more to an older person [Goffin is thirty-seven].

I'm going to have to start thinking younger. Today I feel guilty if I haven't written for a while, but it's harder for me now--I'd like to be better." He pauses and comes up with some thing full of the cynicism his old lyrics would have scoffed at: "You know, I often ask myself if people even listen to rock-and-roll lyrics. I'm not so sure they do." Bernie Taupin isn't so sure either.

And so he published a big, glossy book of his lyrics last year to make sure that people would at least look at them.

They're looking, all right; sales are fine, and Taupin already has a second volume in the works.

Taupin is the superstar among lyricists, and his story is a classic. He

------

Up on the Roof, words and music by Gerry Goffin and Carole King; copyright 1962-3 by Screen Gems-EMI Music Inc. All rights reserved.

-----

started out one day to answer an ad for lyricists in a London music-trade paper but changed his mind and threw the letter away. His mother retrieved it and, unbeknownst to Bernie, sent it along.

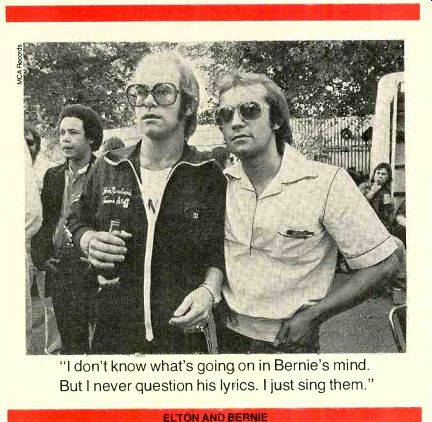

The publishers were impressed and asked him to team up with another correspondent, a young composer named Reggie Dwight-who, as we all know, later changed his name to Elton John.

And Bernie Taupin and Elton John went on to change the course of rock-music history.

Today Elton John is so successful he could sing the London phone directory-detractors insist he might as well be doing just that-but what he mostly sings are Taupin lyrics to his own songs. Those lyrics have been de scribed as "rapidly vapid" (Taupin can write dozens of them in a day), filled with surrealistic non sequiturs. But, says Elton, "I wouldn't tackle any other lyrics apart from Bernie's. They're special to me. They've always inspired me. If Bernie suddenly said he didn't want to write any more lyrics or that he didn't want to write them for me, then that would be it-the end. I'd just have to stop; there'd be no sense in carrying on." BERNIE IS a little less melodramatic about the whole thing. "If Elton stopped writing, I'd still write lyrics." Although he's at the top of this par ticular commercial heap, Taupin says he's not especially at ease. "There's a lot of uncertainty in my writing and some of my ideas are insecure. You can read what you like into my lyrics, view them from many different angles. I like to write songs more ambitious than most."

Some sample Taupin lyrics:

Inside of you I have formed a home,

Outside of you I have cast a dome.

A castle you conceived for me,

This place to rest before I see.

And,

Oh, Daniel, my brother

You are older than me,

Do you still feel the pain

Of the scars that won't heal?

Your eyes have died, but you see more than I,

Daniel, you're a star in the face of the sky.

Elton again: "I don't know what's going on in Bernie's mind. But I never question his lyrics. I just sing them.

--------------

Birth, by Bernie Taupin-Caleb Quaye-Davey Johnstone 1972.

Daniel, by Bernie Taupin and Elton John 1973.

----------

--------- "I often ask myself if people even listen to rock-and-roll

lyrics. I'm not so sure they do." "I know my lyrics aren't poetry

. . . but success with my lyrics has improved my poems." "I don't

really like writing. I like having written."

That's his part of the fantasy, and I just don't go and say, 'What does this mean?' Many music critics, however, would like to know what it all means. They aren't coming up with any quick answers, but Bernie and Elton are coming up with a lot of quick hits. You can barely turn the radio dial these days and nights without coming across a John-Taupin collaboration. They have nine gold singles and twelve gold al bums-but they have only eleven platinum albums (they must be slipping somewhere).

Even after all the success, Elton and Bernie still work together the way they always did-through the mail. Elton sets the lyrics to music and Bernie hears the whole thing when it's done.

They've been known to churn out as many as twenty songs a day that way.

But Bernie knows his limitations. "I know my lyrics aren't poetry. But I do write poetry too, and success with my lyrics has improved my poems. It doesn't make any difference if I'm writing in a garret in Finchley or on a beach in the Caribbean, because I've already had my struggles.

"You know," he says, pausing to push one leg under another, "the audience never realizes what it takes to get there. They don't realize the heart aches, they don't realize that you've had to pay your dues. But it's good to pay your dues." AND now, of course, the dues are paying him. Just a little work on that and it would sound like a lyric Carole Sager might have written: "You've paid your dues/And now your dues are payin' you." Ms. Sager is another Very Successful Lyricist, and her best work is heavy with a sensitivity typical of what Tom Wolfe has called "The Me Decade." Better Days, Help Is on the Way, Good News, and Home to Myself are just a few of the lyrics she has writ ten with a pop-sociological slant. For example:

Nobody's home when you need 'em

Even after you love 'em and feed 'em

-----O Lord Say do not disturb me

This lady's not home today. Or, No more tears left to hide

We have made it through a long and lonely night.

Better days are on our side,

Oh it looks as though we're doing something right.

Those are just two of the lyrics she has written with Melissa Manchester, whom she discovered ooh-oohing out of Bette Midler's back-up chorus line, the Harlettes. The list of her other collaborators reads like a Who's Who of pop composers: Marvin Hamlisch, Pe ter Allen, Lucy Simon, Bette Midler, and, a long time ago, Neil Sedaka ("I was Neil Sedaka's 'Hungry Years,"' she quips, referring to a recent Sedaka album title).

Sager's lyrics are perfect for her collaborators and perfect for the times.

She is also a very unselfish writer who is quite prepared to merge her own writing style into the style and personality of the composer.

-------

(This) Lady's Not Home Today, by Carole Sager and Melissa Manchester 1974.

Better Days (Looks as Though We're Doing Somethin' Right) 1975; The New York Times Music Corp. and Rumanian Pickle Works Music Inc.

---------

"My roots are on Broadway," she says. "I even wrote a Broadway show, Georgie, that flopped. I was depressed for six months after that. The New York Times thought my lyrics were pedantic, pedestrian-and a few other p's. But then I recovered and met Melissa." Her biggest commercial hit has been Manchester's Midnight Blue of a year or so ago. But she keeps trying for more. "All artistic points of view aside, if you don't have a hit, then your album becomes a collector's item.

"I'll tell you how to write a hit lyric.

Make sure the title appears more than once in the song. Have a structured verse-chorus, something that someone can sing back to you on the second listening. Keep it simple. A radio programmer's got to like it even if he had a fight with his wife the night before.

And make sure that the hook of the chorus comes before the DJ picks up the needle.

"But the melody has to get people first, because that's where they hear the hook. Even so, without the lyrics some songs would never see the light of day. If a song has already been written a thousand times-about love, hate, fear, all that-I try to write it a little differently. I don't try to be clever and look for strange rhymes for tomato. And I'm not Bob Dylan; I've never written political songs. If you can reach out to another person that's enough."

"I like lyric writing because it's childlike and it's a puzzle." Brackman

Sager has a very special, intimate way of working with her collaborators.

"Let's say we get together at two p.m. on a Wednesday. Well, then, from two to four we just talk about how we feel, where we're at, what's going on. From that talking, we'll get a common ground for a song that will be honest for both of us. We work together at the piano. I might sing a tune and they might suggest a lyric. We edit each other as we go along. The feedback is immediate.

But my lyrics are written for me; they're cathartic and they make me feel better." But does she like writing lyrics? She has to think a little about that.

"I don't really like writing," she finally says. "I like having written."

JACOB BRACKMAN isn't so sure he likes even that. "I'm very critical about my work," he says. "I'm neurotic about writing lyrics. I always think of things afterward that could have been better." One thing that couldn't be much better is Brackman's long-time collaboration with singer-songwriter Carly Simon. They met at summer camp years ago and have been friends and co workers ever since.

"Lyrics are just something I stumbled on," says the thirty-three-year-old Brackman. "I had been writing maga zine articles, stories, and essays, and Carly came to me because she needed help writing a lyric for a song. So I wrote it for her. It ended up being her first hit, That's the Way I've Always Heard It Should Be:

But you say it's time we moved in together, Raised a family of our own, you and me.

Well, that's the way I've always heard it should be, You want to marry me; we'll marry.6 Since that hit, Jake and Carly have been more or less a team-"more when Carly needs help on the lyrics, less when she writes her own or has some one else write them." Someone else? "I feel bad when she goes to other lyricists," Brackman says. "Maybe she does it to express her independence from me. But then she feels bad when I write for other composers ! Not only has Brackman written with others, he's written with himself-not music, but a screenplay (The King of Marvin Gardens) and a book (The Put On). He is also producing films and is now in the midst of his first musical-comedy project. But his heart-and his art-belong to Carly.

"It is, strange, you know, I'm a guy writing for a girl. But I know her really well and I know what will sit well with her. I try to write things for her that she might write for herself."

-----

That's the Way I've Always Heard It Should Be. 1970 by Carly Simon and Jacob Brackman. Published by Quackenbush Music/Kensho Music, ASCAP.

-----

But Carly alone is not enough of an outlet. "She records only one album a year and maybe uses two or three of my songs. We have the standard fifty-fifty money arrangement most collaborators do, but I can't live off that. I can write more. I'd like to find more people to write with-like Burt Bacharach. I have a whole trunk full of lyrics." Near the trunk sits a radio, which Brackman listens to a lot. "When I hear one of my songs on the radio, I feel a rush of energy," he says. "I do admire some of my work. I like lyric writing because it's childlike and it's a puzzle. I guess I can write a hit song as well as anyone."

MOST rock lyricists--most successful ones, anyway--agree that writing lyrics isn't exactly high art, but, as Goffin says, it isn't exactly hack work either. It is a commercially valuable craft, and those who practice it best reap a financial and (sometimes) critical reward And who knows, perhaps those who put into their lyrics a little more than they know they are putting in will win a different, more lasting fame hi the future, for their words, more than those of the history books, will be the ones that will tell later generations what it was like to be young in the Seventies.

------ "I don't know what's going on in Bernie's mind.

But I never question his lyrics. I just sing them." Elton and

Bernie

Also see:

RECORD OF THE YEAR AWARDS--1976: STEREO REVIEW'S critics and editors select the industry's top artistic achievements.

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)