.

Reviewed by: RICHARD FREED DAVID HALL GEORGE JELLINEK PAUL KRESH STODDARD LINCOLN ERIC SALZMAN

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

ALFVEN: Swedish Rhapsody No. 1, Op. 19 ("Midsommarvaka"). Swedish Royal Orchestra, Hugo Alfven cond. Swedish Rhapsody No. 3, Op. 48 ("Dalarapsodi"); Festspel, Op. 25. Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Stig Westerberg cond. SWEDISH SOCIETY DISCOFIL SLT 33145 $7.98 (from HNH Distributors, P.O. Box 222, Evanston, Ill. 60204).

Performance: Excellent

Recording: Good 1950's vintage

Hugo Alfven recorded his deservedly popular Midsommarvaka (Midsummer Vigil) in 1954, at the age of eighty-two, and it is that performance that is the high point of this disc in both musical-poetic content and documentary value. It was, by the way, the first Swedish stereo recording of symphonic music and was issued over here by Westminster in 1957.

However, this new Swedish Society Discofil release offers a decidedly superior remastering job and shows to best possible advantage the felicitous underlining of contrapuntal de tail and lovely expressive touches that the composer brings to his minor masterpiece of Swedish romantic nationalism. The Dalarap sodi (Dalecarlian Rhapsody), composed in 1937, more than thirty years after Midsom marvaka, is a more dark-hued and sprawling affair, with folk tunes displayed sequentially rather than cleverly combined as in the earlier score. The most arresting touch is the opening ...soprano saxophone solo, evocative of the Swedish birch horn. The Festspel (Festival Piece) with which the disc opens is a hand some ceremonial piece in polonaise style composed for the 1908 inauguration of Sweden's Royal Dramatic Theater in its then new quarters. These 1957 recorded performances by Stig Westerberg were also released here by Westminster some two years later, but again, Westerberg's spirited readings benefit from the expert remastering of this new import disc.

D.H.

------------

Explanation of symbols:

= reel-to-reel stereo tape

= eight-track stereo cartridge

= stereo cassette

= quadraphonic disc

= reel-to-reel quadraphonic tape

= eight-track quadraphonic tape

Monophonic recordings are indicated by the symbol

The first listing is the one reviewed; other formats, if available, follow it.

----------------

J. S. BACH: Six Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord (BWV 1014-1019). Alice Harnoncourt (violin); Herbert Tachezi (harpsichord); Nikolaus Harnoncourt (viola da gamba). TELEFUNKEN 6.35310 two discs $13.96.

Performance: Authentic

Recording: Excellent

J. S. BACH: Six Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord (BWV 1014-1019); Sonata in G Major (BWV 1021); Sonata in E Minor (BWV 1023); Alternate Movements for the Sonatas. Endre Granat (violin); Edith Kilbuck (harpsichord). ORION ORS 79213/5 three discs $13.96.

Performance: Good

Recording: Hard

J. S. BACH: Six Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord (BWV 1014-1019). Jaime Laredo (violin); Glenn Gould (piano). COLUMBIA M2 34226 two discs $13.98.

Performance: Frustrating

Recording: Fine

One of the problems posed by the Bach Violin and Harpsichord Sonatas is balance: the rich, modulated tone of the modern violin simply steals the show from the rigidly static sound of the harpsichord. A violinist's chief means of expression is dynamic; the harpsichordist's is temporal. It is well-nigh impossible to use both without upsetting ensemble and balance, and yet the use of one or the other proves frustrating to both performer and listener.

These three albums offer three varying solutions, all of which work to a degree but still leave unanswered questions.

Granat and Kilbuck on Orion Records present us with the modern violin played in the current high-pressure style. Mr. Granat's execution is violinistically admirable, but it is filled with spurious crescendos and slurs, and there is an overall legato that is detrimental to Bach's highly articulated writing. Ms. Kilbuck, on the other hand, plays a historic instrument by William Dowd in an austerely authentic manner. Not only are the performers' styles incompatible, but the harpsichord sound is so soft that it offers a mere tinkle in the background, which is particularly frustrating in that Ms. Kilbuck is an excellent harpsichordist who understands temporal expression well and is not afraid to use it. This is at tested in her fine performance of the solo movement of the G Major Sonata. Perhaps different microphone placement would have helped us to hear her.

The use of modern violin and piano by the Laredo-Gould team solves the balance problem. Here the equal lines are heard in proper balance, and Mr. Gould's talent for polyphonic clarity comes to the fore as he underlines important thematic entries. But otherwise his treatment of the music is utterly perverse. His articulation is so choppy and arbitrary that the long Bach lines become a farce of trivia. He also chooses to fill in the writing with staccato chords and spacings that properly belong in a night club. Perhaps the most galling feature is the way he breaks chords; his added figurations in the adagio of the E Major Sonata, for instance, completely destroy this magnificent music.

Laredo's reading, however, is superb. His tone is perfect for the style, and he brings that rare combination of articulation and line to the music that reveals Bach in his fullest glory. One wonders how he manages such musical integrity and beauty over such a grotesque accompaniment.

It is typical of any performance associated with the name Harnoncourt that authentic instruments are played in the most uncompromising, authentic style that can be mustered.

This approach, of course, requires arduous research and technical skill. For the modern listener, however, it has both its pros and cons, as demonstrated in the Telefunken re cording of the Bach sonatas. Most admirable is its clarity: the flat, vibrato-less sound of the violin matches that of the harpsichord, and that, together with detailed articulations and much ditachi playing on the part of both per formers, results in a balance that allows us to hear the entire musical complex. It is also enhanced by the use of the viola da gamba on the bass line. Thus we hear three different timbres: solo violin, a single harpsichord line, and a third line of harpsichord and gamba, which helps to clarify the complex weave of the parts.

But Alice Harnoncourt applies Baroque performance practice so rigidly that one feels a basic lack of instinctive musicianship. Each note is firmly attacked (sometimes with a rather ugly result) and immediately subjected to a severe diminuendo, something that becomes a mannerism. The articulation is so separated that there is a lack of line, and the rhythm is so rigid that one gasps at times for a bit of rubato to stretch a line to its climax. Even final retards are denied us, which is musically frustrating in such broadly conceived rhapsodic movements as the openings of the E Major and B Minor Sonatas. In the fast movements, however, the manner works well, for the clarity of the lines and briskness of the tempos make the music sparkle. The final movement of the E Major, for example, is a delight.

Although none of these recordings does complete justice to the works nor allays the frustrations inherent in the music, the Harnoncourt-Tachezi is the most positive approach. The basic problem lies in the music.

Magnificent, yes, but perhaps only performers of it will ever feel complete fulfillment. S.L.

BERLIOZ: Symphonic Fantastique, Op. 14a. Budapest Symphony Orchestra, Charles Munch cond. HUNGAROTON SLPX 11842 $6.98.

Performance: Expansive

Recording: Good

This recording, released for the first time only last year, is the penultimate of the five Munch made of the Fantastique; according to information printed on the jacket, it was assembled from rehearsal tapes made in 1966 as part of the Hungarian Radio's experiments in stereo recording techniques. Perhaps it is be cause of the rehearsal circumstances that the performance is weighted more toward expansiveness than fervor. It is not a dull one by any means, and there is a good deal of fine playing, especially from the strings. It is a Fantastique I would find easier to live with than Munch's valedictory one with the Orchestre de Paris on Angel but less satisfying than either of his two Boston versions. It's surely not a candidate for first choice, in any event, in the face of Martinon's stunning ac count, the elegant versions of Beecham and Monteux, and at least a half-dozen other really distinguished current offerings. R .F.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

COUPERIN: Four Royal Concerts; Les Golds Reunisou Nouveaux Concerts. Thomas Brandis (violin); Heinz Holliger (oboe); Aurele Nicolet (flute); Josef Ulsamer (viola da gamba); Manfred Sax (bassoon); Christiane Jaccottet (harpsichord); others. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON ARCHIV 2723 046 four discs $31.92.

Performance: Exquisite

Recording: Clear

Written during 1714-1715 for Louis XIV's Sunday afternoon petits concerts, Francois Couperin's fourteen Royal Concerts are per haps the most elegant salon music ever conceived. As the title of the second set implies, Couperin, a passionate lover of Italian music, creates a blend of suave French melody propelled by Italianate sequences, of smooth French harmonies spiced with Italianate modulations and dissonance. Never do the two styles clash, but rather become a subtly balanced mixture that only such a genius as Couperin could achieve.

Scored for utility, the Concerts call for continuo and a single melody instrument with an occasional added counter-melody "if one wishes." Taking full advantage of this freedom of instrumentation, this recording sup ports the harpsichord with gamba or bassoon and distributes the various melodic parts among violin, oboe, and flute depending on the character of the music. Thus, what looks dull on paper takes on great variety as the instruments in solo and combination offer a constantly changing timbre.

The style of playing is extremely legato here, and I would prefer a slightly more marked articulation. But this is more than offset by overall beauty of phrasing. The lines are long and sinuous, and this group of musicians deserves high praise for molding them in completely natural contours.

Typical of the French galant style, the melodies are overlaid with a plethora of ornaments, but Couperin intended them all-plus what the performer could add-to be played.

They are all here, too, clear as a bell, and never once does an ornament mar the shape of a phrase. The only questionable practice is the consistent use of the appoggiatura before the beat as an unaccented passing note. I long for that characteristically French mannerism of long, on-beat appoggiaturas. Although all the performers are at home in the style, oboist Heinz Holliger's ornamentation and tasteful divisions are really outstanding.

-----------

The French Bidu

Bidu Sayao as Manon

THIS recital, with its bountiful outpouring of pleasurable "little things," brings to mind the message of the Hugo Wolf song Auch kleine Dinge. The program is, for the mast part, offbeat repertoire, all of it performed with complete stylistic mastery and insinuating charm. It is characteristic of Bidti Sayao, who was never a singer of sweeping prima donna gestures. Nor was she driven by illusions of limitless versatility; content with the range and power of the vocal gifts with which nature generously endowed her, she sought perfection within their natural limits.

The longest selection, "Je voudrais," comes from the long out-of-print recording (Columbia ML 4075) of Debussy's La Damoi setle Elue, made in 1947. Miss Sayao made her American debut under Toscanini in this same work in 1936. French was a language she acquired in childhood. Later studies with Jean de Reszke and extensive appearances in France established her as a mistress of the French singing style. But she exhibits a mastery of the vocal art as well in this sequence of simple songs that are by no means simple to do this well. Her tones are sweet and true, effortlessly produced, with exquisite pianissimos that are to be cherished.

I would have preferred piano accompaniment for the Hahn song and an orchestra be hind the Auber and Ravel arias, of course.

But these were recorded in a less exacting era, and we are fortunate that they were re corded at all in quite acceptable sound for the period (1938-1950). There are useful and in formative notes by producer William Seward, who was enterprising enough to obtain re leases from RCA on three selections. Compliments to all concerned.-George Jellinek BID!) SAYAO: French Arias and Songs. Hahn: Si mes vers avaient des ailes. Duparc: Chanson Triste. Debussy: L'Enfant Prodigue: Lia's Recitative and Aria. Bid(' Sayan, (soprano); Columbia Concert Orchestra, Paul Breisach cond. Debussy: La Damoiselle Elue: Je vou drais qu'il fut dela pris de moi. Bicla Sayao (soprano); Women's Chorus of the University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy cond. Koechlin: Si to le veux.

C'ampra: Chanson du Papillon. Auber: Manon Lescaut: L'iclat de rire. Chopin: Tris tesse. Moret: Le Nelumbo. Debussy: De Fleurs. Ravel: L 'Enfant et les Sortiliges: Toi, le coeur de la rose. Trad. (arr. Crist): C'est mon ami. Bidu Sayao (soprano); Milne Charnley (piano). ODYSSEY (g) Y33130 $3.98.

------------

------------

MAURICE EMMANUEL (1862-1938): Very much worth getting to know.

One of the bites noirs of French music is the question of notes inegales. Here the characteristic rhythmic alteration is turned off and on in a somewhat vexing and inconsistent manner. A passage will be played as written and the repetition will be rhythmically modified. Frequently when Couperin clarifies the situation by specifically calling for inegales , they are ignored. From what I can gather about this contradictorily documented practice, they should be applied, when appropriate, to an entire movement, not haphazardly to small sections or repeats. When they are used in this album, however, they are subtly handled and the flow of the music is not impeded by the galling lumpishness so frequently heard in many so-called "authentic" performances where they are applied with a vengeance.

Despite my quibbles, this is a fine album of a very special repertoire. The overall effect is exquisite, and if these Concerts found favor with Louis, which they did, they are a tribute to that monarch's remarkably high degree of refinement. S.L.

EMMANUEL: Symphony No. 2, in A Major ("Bretonne"). Orchestre Philharmonique de l'ORTF, Jean Doussard cond. POULENC: Concerto in D Minor for Two Pianos and Orchestra. Marie-Jose Billard, Julien Azals (pianos); Orchestre National de l'ORTF, Maurice Suzan cond. INEDITS ORTF 995 035 $7.98 (from HNH Distributors, P.O. Box 222, Evanston, Ill. 60204).

Performance: Good

Recording: Good

Maurice Emmanuel (1862-1938) was born a few months before Debussy and died a year after Ravel; he is remembered primarily as a scholar, his compositions hardly ever per formed or even discussed. He had some of the same teachers as Debussy, and evidently some of the same musical tendencies, but he lacked the forceful originality that might have earned him similar stature. It is certainly time we were able to hear some of his work, and the later of his two symphonies is regarded as one of his best pieces. It was composed in his seventieth year, originally titled La Legende du Roi Grallon, and, since the city of Ys, the legend's setting, is in Brittany, Emmanuel used Breton folk themes in the two outer movements. Through the four movements, the work is charged with a spiky sort of vigor; its coloring is bright but hardly shimmering voluptuousness is not part of its make-up The language has more in common with Lalo and Roussel than with any off Emmanuel's other early or late contemporaries-but that is only a hasty attempt at describing something that actually seems unique. The symphony, in any event, is stimulating, original, and rather aggressively refreshing. It is given .a very spirited performance here, one that invites repeated exposures.

The Poulenc concerto, by now so familiar a work one hardly expects to see it on a label devoted to underexposed material, is given a good, even brilliant performance, but one in which the crisp, dry, ironic qualities of the work seem gratuitously underscored at the expense of its ingratiating qualities. These elements seem to me more equably balanced in most of the other current recordings of the concerto, among which my own preference remains the one in which the soloists are Poulenc himself and his longtime associate Jacques Fevrier (Angel S-35993). The new version is more handsomely recorded, though, and the Emmanuel symphony is very much worth getting to know. R.F.

FRANCK: Symphony in D Minor; 126 demption-Morceau Symphonique. Orchestre de Paris, Daniel Barenboim cond. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2.5Y0 707 $7.98, 0 3300 707, $7.98.

Performance: Craftsman-like

Recording: Spacious

For the most part Barenboim has his orchestra at the top of its form here: even the horns betray none of the saxy quality one is almost resigned to accepting from French orchestras.

The English horn player does not make enough of his moments in the slow movement to justify the solo billing he receives, the trumpet tone shows an occasional harshness, and the spacious recording itself is sometimes a little fiery, but none of these little shortcomings would matter much if there were more momentum in Barenboim's reading. The very opening is most promising-eloquent, brooding, suitably mysterious-but in the first movement proper the music fails to take wing, and the finale too seems earthbound in its lack of tension. It is as if Bareriboim were somehow too fastidious or too embarrassed to acknowledge the music's ecstatic character and settled for an approach more craftsman-like than inspired.

But you may listen with a more sympathetic ear if you happen to be fond of the Morceau Symphonique from Franck's 1872 oratorio Redemption (on which not a word of information is offered in DG's trilingual annotation).

The shorter work, which has not been around for a while, is given a gorgeous, all-out performance, just the sort one wishes Baren boim had given the symphony. R.F.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

HANDEL: Messiah. Elly Ameling (soprano); Anna Reynolds (contralto); Philip Langridge (tenor); Gwynne Howell (bass); Chorus and Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Neville Marriner cond. ARGO D18D3 three discs $20.94.

Performance: Splendid

Recording: Splendid

In Baroque opera and oratorio, there never was such a thing as a definitive version of a work. Each performance was unique. As singers were changed, so were their requirements. Each audience had its own tastes, and composers in this capricious era simply altered their works to fit the exigencies of the occasion. Thus every time Handel presented his Messiah he made whatever changes were needed to fit the requirements of the situation and also (and this is most important) made changes that fit his own musical fancies at that time. Therefore, some changes are purely practical and others show signs of creative growth. The problem, then, is to sort out those changes that were the result of necessity and those that were prompted by a musical rethinking of the work at hand. Christopher Hogwood, who has edited the version presented in this recording, has chosen to present what he considers the closest to Handel's original concept of the work; through a careful study of various documents, manuscripts, and librettos, he has painstakingly reconstructed the version first presented in London on March 23, 1743.

Now many of us have grown up on this work in a sort of amalgamated version developed through the years from Mozart to Ebenezer Prout, and Dogwood's version will, therefore, necessarily startle us every now and then. Some of the changes here seem to be for the better; others lead one to think that Handel's second thoughts on the music were better than his first. The charming recitative sequence for soprano, for example, which follows the Pastoral Symphony substitutes a short arioso for "And lo, the angel of the Lord." I miss the rustle of the angels' wings, and, in a way, the substitution kills the impact of "Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion." But I must admit that the unfamiliar arioso is itself a beautiful piece of music. Whether or not we like the changes, though, we are forced to re think a masterpiece, and that forced rethinking is not at the behest of a capricious editor but of the composer himself.

Mr. Hogwood has also come to terms with the problem of ornamentation. As Handel himself well knew, ornamentation can be overdone and detrimental to the work. In this performance it is both discreet and tasteful.

Appoggiaturas abound and cadenzas are add ed, as are certain divisions. Never are they there for vocal display, but always for enhancement of the music itself. Handel would have been fortunate indeed to have had his singers show such restraint and musicianship.

The use of rhythmic alterations, however, is a different matter. Using French manner isms in Italianate vocal music in England is, at best, questionable. Handel was perfectly capable of indicating when he wanted dotted rhythms, and they are out of place in "And the glory of the Lord." They also kill the contrasting feeling of "peace" required in the second section of "Rejoice greatly." Performances of Messiah have often been marred by excessively slow tempos, but Neville Marriner's briskness and drive work wonderfully in such choruses as "For unto us a Child is born" and the startlingly angry "He trusted in God." On the other hand, the over ture lacks dignity because of its too-ardent drive, and the almost scherzo quality of "And with his stripes" does violence to the text.

Despite certain lapses in tempo, this reading is unique in its continuity. The usual pause and banding between each number have been dispensed with, and one piece flows dramatically into the next in a way that creates a vast unity of mood change and drama. The soloists are excellent, and Handel would no doubt be pleased with their expressive projection. The real hero of the performance, however, is Philip Langridge. His sensitive musicianship is supported by a rich, clear voice which is capable of stunning coloratura and subtle coloration of the text.

Quibble as one may about details of this version and performance, Christopher Hogwood deserves credit for his musicianly scholarship, and Neville Marriner for his thrilling concept of this masterpiece. They have both brought something new and fresh to a work which is itself the essence of the new and the fresh. S.L.

HAYDN: String Quartets, Op. 77, Nos. I and 2 (see Best of the Month, page 87) LISZT: Piano Concerto No. 1, in E-Rat Major (see TCHAIKOVSKY) MAHLER: Symphony No. 1, in D Major. Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Zubin Mehta cond. LONDON CS 7004 $6.98.

Performance: Mostly splendid

Recording: Excellent

Zubin Mehta's realization of Mahler's First Symphony, like his often impressive reading of the Resurrection Symphony, just misses being top-drawer because of erratic first-

movement tempos. In this instance the conductor rushes the climax, dissipating its inherent impact and making the remaining pages of the movement rather pointless. Things improve with the succeeding Landler movement, though one could ask for a little less schmaltz in the trio section. It is in the final two movements, though, that Mehta and the Israelis really hit their stride, delivering wonderfully vital and colorful performances of the parodistic funeral march and turbulent finale. There are delicious bits of detailed underlining in terms of both timbre and flexibility of phrasing, yet the overall line is never lost. The sonics throughout are first-rate.

D. H.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

MONTEVERDI: Arias, Canzonettas, and Recitatives. Lettera Amoroso; Conche soavita; Lament() d'Arianna. L'Orfeo: Mira, deh mira, Orfeo . . . In un fiorito prato. L'In coronazione di Poppea: Disprezzata Regina; Tuche dagli avi miei . . . Maestade, che pre ga; Addio Roma. Cathy Berberian (soprano); Concentus Musicus Wien, Nikolaus Harnoncourt cond. TELEFUNKEN 6.41956 AW $7.98.

Performance: Musico-dramatic

Recording: Vivid

Cathy Berberian is so firmly associated with contemporary music of the far-out variety (and, secondarily, with the revival of turn-of-the-century parlor camp) that a collection of Monteverdi comes as a surprise. But the musical intensity and affective qualities of this music are a perfect match for Berberian's musico-dramatic talents. Her style is not what one would traditionally regard as "real" Baroque, and her voice, never overwhelmingly beautiful, sometimes comes uncomfortably close to the edge of stridency. But frankly, if it were up to me, I would make every singer of dramatic music-of the ancient variety and of the not-so-ancient as well-study these performances to learn something about how ...

--- CATHY BERBERIAN: tremendous musical and dramatic intensity.

... to play in the great and wonderful musical theater of the human emotions which Claudio Monteverdi was the first in modern times to explore.

The outstanding--but also the most disputable--performance here is Lamento d'Ari anna, one of the most famous pieces of an age and, paradoxically, one of the most obscure.

The Lamento was the hit tune, and is the only surviving music, from an opera on the subject of Ariadne. It has come down to us in two forms: a dry "lead-sheet" version for voice and basso continuo and a later, juicier madrigal arrangement for five voices which gives us a much better idea of what this music is really about. The version here seems to be a concoction made up from the two, arranged for solo voice with instrumental parts-accompaniments, interludes, or ritornellos-derived from the madrigal. Whatever the musicological verities, the musical results magnificently complement the pathos and power of the vo cal interpretation. For the first time, I know what Monteverdi's contemporaries meant when they described the devastating impact of this music! My principal quarrel with this record has to do with the production. The album provides no texts, no translations, and almost no useful information. The Lamento, which ought to be the lead-off piece, is buried as the third band on a side that opens with the rather dull Lettera Amorosa. This free recitative, published in 1619 as part of the composer's Seventh Book of Madrigals, is a throwback to the monotonous recitative style of the first operas of Peri and Caccini. Even Cathy Berberian can not raise it up to any reasonable level of musical interest. Another work from the same set, "Con the soavita" for voice and instruments, is by contrast a thoroughly engaging musico dramatic work set to a poem by Giambattista Guarini, and it is affecting in performance.

But even here it is a shame not to be able to follow the subtleties of Monteverdi's and Berberian's interpretation of one of the finest lyrics of the period.

Side two consists of operatic excerpts: the messenger scene from Orfeo and three of Ottavia's stirring scenes from L'Incoronazione, beautifully realized moments of tremendous musical and dramatic intensity. Miss Berberian is aided by good supporting singers in two of the dramatic excerpts, by the suave playing of the Concentus Musicus, and by excellent recordings. E.S.

MOZART: Piano Concerto No. 14, in &Hat Major (K. 449); Piano Concerto No. 24, in C Minor (K. 491). Murray Perahia (piano); English Chamber Orchestra, Murray Perahia cond. COLUMBIA M 34219 $6.98, MT 34219 $6.98.

Performance: Very good

Recording: Spacious

In his Schumann, Chopin, and Mendelssohn recordings, Murray Perahia has shown him self a cultivated, thoughtful, and frequently poetic performer. His first Mozart record is definitely not a disappointment. He does not use the two concertos as mere "vehicles" but presents them as pleasures too deep to keep to himself. The release also marks Perahia's conducting debut on disc, and in this department, too, there is little room for complaint.

The dual role is especially successful in the earlier work, with its chamber-music proportions, but a division of labors might have been advisable in the bigger and more dramatic C Minor. Technically there is never less than a complete mesh of solo and orchestral elements, and the slow movement of K. 491 is sheer perfection, but the darker character of its outer movements seems less fully realized than it might have been with a little more flexibility in pacing. Still, there is nothing second rate here (including Perahia's tasteful cadenzas for K. 449), and those attracted to this particular coupling should find this spaciously recorded disc more rewarding than the one on Deutsche Grammophon by the late Giza Anda. R.F.

PERSICHMI: String Quartets Nos. 1-4. New Art String Quartet. ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY ASU-1976-ARA two discs $10.00 (from Persichetti Quartets, Department of Music, Arizona State University, Tempe, Ariz. 85281).

Performances: Very good

Recording: Close, clear

Vincent Persichetti is a major name in American music-not only as a composer but, through his long association with Juilliard, as one of the half-dozen major composition teachers in this country. Yet his music is not

really all that well known. In fact, if one thinks of Persichetti at all, one tends to think of a genial sort of American-school music, conservative but with bite, This image actually applies only to a certain period of his work, exemplified here by the modal and polytonal Second Quartet of 1944. The Third Quartet of 1959 verges on atonality and twelve-tonery, and the Fourth Quartet, quite far-out in its way, is a curiously effective mixture of traditional and ultra-modern elements in a style that is highly fragmented and yet cohesive.

Persichetti's skill and fluency is already evident in the Hindemithian First Quartet and is always there through all the changes of later years. I am not willing to venture any predictions about the possible longevity of these works, but they do represent an important non-academic serious side of contemporary American music.

It is of note that this music comes to us from the Sun Belt. The New Art String Quartet, an eminently able ensemble, is in residence at Arizona State University, which has published these recordings. The idea of university nonprofit records of this type has of ten been discussed, but the state of university finances these days rarely permits such extravagances. I'm glad to know someone will spend money on musical culture. E. S.

POULENC: Concerto in D Minor for Two Pianos and Orchestra (see EMMANUEL) SAINT-SAENS: Violin Concerto No. 3, in B Minor, Op. 61.

VIEUXTEMPS: Violin Concerto No. 5, in A Minor, Op. 37. Kyung-Wha Chung (violin); London Symphony Orchestra, Lawrence Foster cond. LONDON CS 6992, $6.98.

Performance: Stylish

Recording: Good

Both concertos here are virtuoso vehicles, and Kyung-Wha Chung is not only equal to their purely violinistic demands but makes every effort-by searching out a balance be tween display and lyrical elements-to make the music sound better than it actually is. Her playing is elegant and chic, but it never be comes cold or merely tinselly. She excels in the slow movements of both works. Conductor Lawrence Foster abets Miss Chung handsomely, and London's recording staff has done a fine balancing job throughout, especially in the Vieuxtemps. The Saint-Saens, re corded two years after the Vieuxtemps, in the spring of 1976, sounds just a shade more closely miked in the soloist department, but not uncomfortably so. D . H .

SCARLATTI: Stabat Mater. Mirella Freni (soprano); Teresa Berganza (mezzo-soprano); Paul Kuentz Chamber Orchestra, Charles Mackerras cond. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON ARCHIV 2533 324 $7.98.

Performance: Straightforward

Recording: Excellent

Commissioned for the same forces as Pergolesi's later but more celebrated setting of the text, and by the same Neapolitan society that commissioned the Pergolesi work, Alessandro Scarlatti's Stabat Mater inevitably be came the model for the younger composer.

But the similarities stop there. While Pergolesi looks forward to the simpler harmonies and textures of the Classical era, Scarlatti indulged himself in the rich chromatic harmonies and the intricate counterpoints of the high Baroque.

The performance is a straightforward one.

My first impression was that a great deal more vocal ornamentation should have been applied; the wonderful trills of Mirella Freni and Teresa Berganza leave no doubt that they could easily fill in the lines with all manner of divisions. Further hearings, however, convinced me that they are probably quite right in not doing so, leaving the lines unadorned so that the starkness of the writing matches the austerity of the poem.

Both soloists are excellent. Freni's is a hard, clean sound, well focused and instrumentally conceived. Berganza, on the other hand, offers a richer sound with a warm vibrato. But the duets do not come off as well as the solos because of the balance. Freni's voice simply cuts through the texture, relegating Berganza's role to that of a shadow, albeit a lovely one. S.L.

SCHOENBERG: Verklarte Nacht, Op. 4; Chamber Symphony No. 1, Op. 9; Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21; Ein Stelidichein; Herzgewachse, Op. 20; Three Pieces for Chamber Orchestra; Nachtwandler; Lied der Waldtaube; Die eis erne Brigade; Weihnachtsmusik; Serenade, Op. 24; Wind Quintet, Op. 26; Der Wunsch des Liebhabers, Op. 27, No. 4; Der neue Klassizismus, Op. 28, No. 3; Suite, Op. 29; Ode to Napoleon, Op. 41; Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment, Op. 47. June Barton (soprano); Anna Reynolds (mezzo-soprano); John Shirley-Quirk (bass-baritone); Gerald English (reciter); chorus; London Sinfonietta, David Atherton cond. BRMSH DECCA SXL 6660-4 five discs $34.90 (available through London Records).

Performances: Superbly musical

Recording: Excellent

SCHOENBERG: Serenade for Seven Instruments and Bass Voice, Op. 24. Kenneth Bell (bass); Light Fantastic Players, Daniel Shulman cond. NONESUCH H-71331 $3.96.

Performance: Light and lively

Recording: Very good

SCHOENBERG: Chamber Symphonies No. 1, Op. 9B, and No. 2, Op. 38. Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, Eliahu Inbal cond. PHILIPS 6500 923 $7.98.

Performance: Heavy

Recording: Fairly good

It was Arnold Schoenberg more than anyone else who put chamber music in the forefront of the development of modern music.

------ DANIEL SCHULMAN A skillful, lively Schoenberg serenade

Schoenberg's chamber-music tradition was really an extension of the great line from the Viennese classics through Schumann and Brahms. In the earliest works there is a strong Wagnerian influence, and this carries over into the expressionist period of Pierrot Lunaire. Schoenberg's early twelve-tone music is very closely allied to the neo-Classical movements--the sort of thing he satirized in his little cantata "The New Classicism" (what he meant, of course, was that his classicism was the real one). There are even turgid twelve-tone bits of Twenties jazz buried in these serenades and sonatas. Then there is a freer, final twelve-tone style represented by works written during and after World War II--the Ode to Napoleon (for reciter, piano, and strings) and the Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment.

The Schoenbergian paradox is that these works all belong in the context of the traditional Classical/Romantic concert. They were conceived that way and they must be interpreted squarely in that tradition. But the traditional concert, quite filled to brimming with masterpieces, imitations, and revivals, simply has no place for a music so disturbed and disturbing, so monumentally important, personal, and ugly. The Landon Sinfonietta, an outstanding chamber music organization founded by David Atherton in 1967, is the perfect solution. It is an organization specializing in the great modern tradition--and, most important, in recordings as well as concert performance. Although the organization is new, its players are top English musicia ns trained in the great tradition--a perfect contbination for Schoenberg. In short, they play this music with the same care, big line, and attention to detail that

they would give Beethoven or Brahms. The results may not often soiand beautiful but they sound like music. Schclenberg (who used to say, "I am not avant -garde, only badly performed") would have been pleased.

The contents of the album are a bit curious: all the chamber works of Schoenberg minus the string quartets and the string trio-but the unbearable wind quintet is included. Also included is a lush performance of the original sextet version of Verklarte Nacht, a very mu sical and dramatic Pierrot by Mary Thomas, and the surprisingly grateful serenade works from the 1920's. More unusual are the unfinished chamber-orchestra pieces of 1910 in a Webernesque idiom, a dreadful cabaret song from. 190L and two surprising tonal works from the period around World War I: a march and a Christmas carol fantasia (including Silent l.qightq). The whole huge set of five records its extremely well produced.

The surprising appeal of Schoenberg's sere nade style is even more successfully brought out in a charming performance of Op. 24 by Daniel Shulman and the Light Fantastic Play ers on Nonesuch. These players are skillful and lively (except for the bass voice solo, al ways a problem), and they convey the quality of fantasy in Schoenberg's music-a quality often either overlooked or driven into the ground. In fact, that is exactly what is wrong with the Chamber Symphony performances on Philips; these heavy recordings lack color and imagination. A pity too, since the roman tic Second Chamber Symphony deserves to be better known (it is really written for a larg ish orchestra and is omitted from the Decca set), and the composer's own large orchestral version of the First Chamber Symphony is not exactly a repertoire item either. E.S.

SIBELIUS: Four Legends from the Kalevala, Op. 22; In Memoriam, Op. 59. Hungarian State Symphony Orchestra, Jussi Jalas cond. LONDON CS-6955 $6.98.

SIBELIUS: Finlandia, Op. 26, No. 7; Music for Kuolema, Opp. 44 and 62; Scenes Historiques, Opp. 25 and 66. Hungarian State Symphony Orchestra, Jussi Jalas cond. LONDON CS-6956 $6.98.

SIBELIUS: King Christian H Suite, Op. 27; Swanwhite Suite, Op. 54; Andante Festivo. Hungarian State Symphony Orchestra, Jussi Jalas cond. LONDON CS-7005 $6.98.

Performances: Prosaic

Recordings: Not the best

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

SIBELIUS: Four Legends from the Kalevala, Op. 22; Karelia Suite, Op. 11. Helsinki Radio Symphony Orchestra, Okko Kamu cond.

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 656 $7.98.

Performance: On the button

Recording: Excellent

Being Finnish, as both of these conductors are, may or may not be an advantage in interpreting the music of Sibelius; Beecham, Koussevitzky, Bernstein, Ormandy, and Karajan, among others, have given ample proof that the "You don't have to be . . ." theory can apply in music too. Being the composer's son-in-law as well does not seem to be much of an advantage to Jussi Jalas, whose recordings with the Hungarian State Symphony Orchestra are of interest mainly because they fill a number of gaps in the current discography.

The King Christian II Suite, missing from the catalog for several years, turns up with a sixth movement- a "Fool's Song" which has been recorded independently (usually with a tenor) but never as part of the suite and never issued in this country. The Andante Festivo, apparently another premiere recording, is not to be confused with the familiar Festivo (Tempo di Bolero) which concludes the first set of Scenes Historiques. Four of the seven Swan-white numbers are on the final side of Paavo Berglund's Angel set of the Kullervo Sympho ny (SB-3778), as is the "Scene with Cranes" from Kuolema, and Leif Segerstam conducts the Canzonetta (one of the two Op. 62 pieces from Kuolema) on Bis LP-19. The Valse Romantique (the other Op. 62 piece) and both sets of Scenes Historiques are otherwise unavailable, and the only alternative version of In Memoriam is the 1938 Beecham recording, recently reissued on Turnabout O THS-65059.

Unfortunately, Jalas' performances are very much of a stopgap quality, consistently prosa- is rather than satisfying. Valse Triste 'and Maiden with the Roses (in the Swanwhite se quence) are reduced to banality, and there is little hint of majesty in this Finlandia. The orchestral playing is competent but hardly distinguished, and the sound-hard, wiry, shallow-is not an asset. ( London did not send its own recording crew to Budapest.) The best of these three discs, both musically and technically, is the one with the Four Legends, superior to Sir Charles Groves' reading on Angel S-37106, but not to Lukas Foss' on Nonesuch H-71203. All of these, however, are clearly outclassed by the new Deutsche Grammophon version under Okko Kamu, who has already demonstrated both his feeling for the Sibelius idiom and the quality of his Helsinki Radio Orchestra. With the first notes of Lemminkainen and the Maidens of Saari we are given notice that this version of the cycle is to be an Event, and that promise is grandly fulfilled in the forty-five minutes of music that follows.

Kamu restores The Swan of Tuonela to its original position as No. 3 in the sequence, a decision which in itself is not very important; what does matter is that the most familiar part of the cycle emerges with a freshness and elo quence one hardly expects of it, let alone takes for granted. But there isn't a superficial or perfunctory bar in these performances. In the Karelia Suite, too, both interpretation and execution are on the button, and DG's engineers have captured everything with a sumptuous realism that is a pleasure in itself. This record is indispensable to Sibelians, whose number it may well increase, and who must hope now for coverage of the less familiar works from the same source. R.F.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Piano Concerto No. 1, in B-flat Minor, Op. 23. LISZT: Piano Concerto No.

1, in E-flat Major. Horacio Gutierrez (piano);

London Symphony Orchestra, Andre Previn cond. ANGEL S-37177 $6.98.

Performance: A romp

Recording: Very good

Of the recording of Tchaikovsky concertos there is no end. The formula is to take the latest keyboard bronco buster and let him ride the old nag-kick some life into her, as it were.

Horacio Gutierrez, born in Cuba and educated in this country, took the now required Tchaikovsky Competition medal in Moscow.

He is impressive in a flashy, good-natured, hard-edge sort of way. He and Previn literally romp through these scarred battlegrounds with scarcely a thought for the dead and the wounded left behind from past engagements.

I never thought Tchaikovskian and Lisztian heroics, musings, and breast-beatings could actually sound cool, lightheartedly brilliant, even elegant, but they do here. E.S.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

TCHAIKOVSKY: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35; Serenade Melancolique, Op. 26. Arthur Grumiaux (violin); New Philharmonia Orchestra, Jan Krenz cond. PHILIPS 9500 086 $7.98.

Performance: Warm, lyrica

Recording: Good

Arthur Grumiaux espouses a broadly lyrical view of the violin concerto and presents the score complete, with none of the cuts in the end movements favored by many performers

over the years. I myself am not wildly fond of the concerto and confess a predeliction for the sort of razzle-dazzle performance style of violinists of the Auer school. In his aristocratic Franco-Belgian way, though, Grumiaux makes a very strong case for a more leisurely and expansive approach in which the lyrical aspects of the piece receive their just due and perhaps something more. Grumiaux's playing of the poignant Serenade Melancolique, which fills out side two, is a perfect gem of its kind.

Polish conductor Jan Krenz leads the New Philharmonia in highly sympathetic accompaniments throughout. The Philips recording is just fine, the playing surfaces noiseless.

D.H.

VERDI: La Forza del Destino (see Best of the Month, page 84) VIEUXTEMPS: Violin Concerto No. 5, in A Minor, Op. 37 (see SAINT-SAENS)

VILLA-LOBOS: Concerto for Guitar and Small Orchestra. Turibio Santos (guitar); Jean-Francois Paillard Chamber Orchestra, Jean-Francois Paillard cond. Mystic Sextet. Maxence Larrieu (flute); Lucien Debray (oboe); Henri-Rene Pollin (saxophone); Fran cois-Joel Thiollier (celesta); Lily Laskine (harp); Turibio Santos (guitar). Five Preludes.

Turibio Santos (guitar). MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 3397 $3.50 (plus 950 handling charge, from Musical Heritage Society, Inc., Oakhurst, N.J. 07755).

Performance: Deft

Recording: Very good

There are already two fine recordings of the Villa-Lobos guitar concerto: Julian Bream (RCA LSC-2606) offers the concerto and the preludes but substitutes the Choros No. I and some other solo pieces for the Mystic Sextet; and John Williams (Columbia M 33208) couples the concerto with the extraordinarily popular Concierto de Aranjuez of Rodrigo.

Santos' playing is never less than fully competitive with that of his better-known rivals, and the choice of couplings inclines me to ward the MHS disc, since I find the seven-minute Mystic Sextet of 1917 one of the most intriguing works of its kind-as Gallic in spirit, curiously, as much of Milhaud's music of this period is Brazilian. In the more or less continuo role assigned to the guitar in the sex tet, Santos blends ideally with his deft associates. Paillard is his dependable self in the concerto, and the recorded sound is very good indeed. R. F.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

VIVALDI: 11 Pastor Fido, Op. 13. Jean-Pierre Rampal (flute); Robert Veyron-Lacroix (harp sichord). RCA , FRLI-5467 $7.98, FRS 1-5467 $7.98, FRK1-5467 $7.98.

Performance: Charming

Recording: Fine

Advertised as suitable for musette, vielle, flute, oboe, or violin, the six sonatas that make up Il Pastor Fido reveal an intimate and graceful side of Vivaldi rarely heard in most of his music we are apt to encounter today.

Eschewing the more exotic instruments listed on the title page, Rampal performs the entire opus on the flute. As usual, his playing is tech nically perfect and brilliant. Supported by the imaginative continuo playing of Veyron ( Continued on page 138)

Lacroix, he brings out the light elegance of these works through clear articulation, brisk tempos, and facile ornamentation. The results are delightful.

S.L.

RECORDINGS OF SPECIAL MERIT

WAGNER: Gotterdammerung (Orchestral Excerpts). Dawn and Siegfried's Rhine Journey; Siegfried's Funeral March; Brunnhilde's Immolation and Finale. London Symphony Orchestra, Leopold Stokowski cond. RCA ARL1-1317 $7.98, 0 ARSI-1317 $7.98, ARK1-1317 $7.98.

Performance: Gorgeous

Recording: Gorgeous

WAGNER: The Ring of the Nibelungs (Orches tral Highlights). Das Rheingold: Entrance of the Gods into Valhalla. Die Walk ure: Ride of the Valkyries; Wotan's Farewell and Magic Fire Music. Siegfried: Forest Murmurs. Got terdammerung: Siegfried's Rhine Journey; Siegfried's Funeral March; Finale. National Symphony Orchestra, Antal Dorati cond. LONDON CS-6970 $6.98,CS5-6970 $7.95.

Performance: Brilliant

Recording: Sumptuous

In his latest (fourth? sixth?-one tends to lose count after so many of them) recording of Gotterdammerung excerpts, as arranged by himself, Stokowski has eliminated the segment "Siegfried's Death," which he included in his London/Decca version with the same orchestra a dozen years ago (SPC-21016). I miss that noble passage, which enhances the Funeral March just as the "Dawn" fragment does the "Rhine Journey"; Toscanini seems to have been the only conductor who consistently included it in his concert performances and recordings. The new recording, though, is more refined, more genuinely exalted than the London Phase-4 version, and RCA's production team can take a good share of the credit: the sound is as gorgeous as the performance-rich, vibrant, beautifully balanced.

The long Immolation Scene is somewhat less convincing as an orchestral piece than its two companion pieces, but it would take a harder heart than mine to find it unattractive as presented here. Stokowski, who will be ninety five this month (April 18), is still the sorcerer supreme.

Dorati, as it happens, also has a birthday this month (seventy-one on April 9), and his Wagner collection is a stunning testimonial to his own powers of sorcery. Perhaps more than any other recording the National Sym phony has made since Dorati became its mu sic director in 1970, these performances (taped in 1975) demonstrate the magic he has wrought. He steps down at the end of this sea son with his mission in Washington largely accomplished: he has given the nation's capi tal a more than respectable orchestra, capable of taking on anything. Here there is not only brilliance to burn, but compassion to move us in Wotan's Farewell, real breadth in the Rheingold excerpt, solemn grandeur in the Funeral March, downright enchantment in "Forest Murmurs." The "Rhine Journey" alone might have been a little more animated, but it is as beautifully played as the rest. Lon don's sumptuous sonics give us strings richer than rich, brass burnished to a lambent glow.

R.F.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

WAGNER: Rienzi. Rene Kollo (tenor), Cola Rienzi; Siv Wennberg (soprano), Irene; Niko laus Hillebrand (bass), Steffano Colonna; Jan is Martin (soprano), Adriano Colonna; In geborg Springer (soprano), Peace Herald; Theo Adam (bass), Paolo Orsini; Siegfried Vogel (bass), Raimondo; Peter Schreier (tenor), Baroncelli; Gunther Leib (baritone), Cecco del Vecchio. Leipzig Radio Chorus and Dresden State Opera Chorus; Dresden State Orchestra, Heinrich Hollreiser cond. ANGEL SELX 3818 five records $34.90.

Performance: Solid

Recording: Good

Richard Wagner was a struggling Kapellmeister in Riga when he began writing Rienzi in 1839; he completed it in Paris as a frustrated and penniless exile the following year. Never theless, it was this opera, conceived in misery and written under the most distressing cir cumstances, that started Wagner on the road to future glory. Performed by a cast that in cluded soprano Wilhelmine Schroder-Devri ent and tenor Aloys Tichatchek, two of the era's most brilliant singers, Rienzi was en thusiastically received in Dresden on October 20, 1842.

The opera's first complete recording, pro duced in that same city, contributes signifi cantly to a well-rounded view of Wagner's ar tistic development. Even The Flying Dutch man, generally regarded as a "transitional" work, seems to be mature Wagner compared with this early effort. Rienzi, plain and simple (although it is neither) is grand opera built on the French models of Spontini and Meyer-

beer. Epic in scale (five acts) and rich in pageantry, it offers an elaborate ballet, battle sequences, and a final conflagration. Of "music drama" there is not a trace: scenas a la Weber, arias with cabalettas, and vocal ensembles follow one another in a manner not far re moved from the procedures of Bellini, whom the finale of Rienzi's first scene is startlingly indebted.

The opera's plot, though based on Bulwer Lytton's famous novel, also borrowed many devices from Auber's enormously successful opera Masaniello (1828). Just the same, the typical Wagnerian elements are already there:

a hero confronted with and eventually de stroyed by hostile forces despite the heroic devotion of a woman. The latter in this in stance is Irene, Rienzi's sister. Their near-incestuous relationship is further complicated by the fact that Adriano, Irene's mixed-up suitor, is interpreted by a female singer.

Musically, on the other hand, there is much to enjoy in Rienzi. It does suffer from excess; the lengthy recitatives delay the action and some brilliantly conceived passages are diluted by repetition. Still, there is no denying the effectiveness of the ceremonial music, the choral pieces, though harmonically uneventful, are stirring, and the familiar vocal high lights (Rienzi's Prayer, Adriano's big dramatic scene) sound even more impressive in context. With their anticipations of Tannhauser and Lohengrin, the last three acts are clearly superior to the first two.

The singing here, while not ideal, is good enough to give us a respectable account of this historically important opera. The title role is cut from a vocal fabric Wagner later remodeled to fit Tannhauser: its high-placed clarion sound calls for a Melchior or, at the very least, a Vickers. Kollo's light voice is severely taxed by the requirements; he sounds un comfortable and at times unpleasant in the high tessitura, but he delivers the Prayer movingly and in a good vocal estate.

Casting Adriano for a woman in trousers was a severe miscalculation on Wagner's part-it may be the single most powerful reason for keeping Rienzi off the stage in modern times. In any case, the role calls for a voice of the Ortrud-Venus type, whereas Janis Martin is more of an Elsa-Elisabeth. This considera tion aside, she serves the music well, at times rising to impressive heights. The young Swedish soprano Siv Wennberg also scores impressively in the part of Irene. Her powerful metallic timbre and easy command of the high register show promise of a great future Brunnhilde. In the present context, however, it is Miss Wennberg who supplies the steely and resolute tones and Miss Martin (as Adriano) who delivers the softer, more feminine ones-and the absurdities are thereby compounded.

There are two fine bassos in the cast: Nikolaus Hillebrand as Colonna, Rienzi's arch enemy, and Siegfried Vogel as the papal emissary who announces Rienzi's excommunica tion. Peter Schreier makes a notable contribution in the small role of Baroncelli, but Gunther Leib is weak as Cecco, the fellow-turncoat. Nor does Theo Adam lift the role of Orsini to a significant level. Heinrich Hollreis er may not be the most exciting interpreter of this music (it would be fascinating to let Sir Georg Solti loose on it), but he gets solid results from both orchestra and chorus and keeps the action moving without making the opera seem longer than it is. G.J.

WAGNER: The Valkyrie. Alberto Remedios (tenor), Siegmund; Margaret Curphey (soprano), Sieglinde; Clifford Grant (bass), Hunding; Norman Bailey (baritone), Wotan; Ann Howard (soprano), Fricka; Rita Hunter (soprano), Brunnhilde; others. English National Opera Orchestra, Reginald Goodall cond. ANGEL O SELX-3826 five discs $35.95.

Performance: Dignified and stately

Recording: Good live

I am a strong proponent of opera in English, but I do think you ought at least to be able to demonstrate redeeming social value in a translation. Just as the Germans long ago naturalized Shakespeare, the English have long tried to adopt the Ring as a national epic with decidedly mixed results.

This recording is taken from a complete English Ring translated by Andrew Porter and produced with an all-British cast at the English National Opera (formerly Sadlers Wells) under the direction of Reginald Goodall. The performances roused great rapture among our overseas confreres, which demonstrates only that the English can work up a great deal of enthusiasm over luke-warm beer.

The performance, like the translation, is High Church-dignified and stately. What is lacking is passion and anything like elevated poetry. Gone forever are the old translator

( Continued on page 142)

stand-bys-the "thou"s and the "doth"s and the "me-thinks"s. But we are still in the never-never land of translatorese with lines (selected almost at random) such as "Slight are they/unworthy your care" (meaning Siegmund's wounds are not worth Sieglinde's trouble) and "Who are you, say, who so stern and beauteous appear?" and "Fearful is the fate I'll pronounce." Like an over-restored picture, the patina of antique poesy and rhetoric has been removed, exposing the careful touch-up job underneath. This is the faithful ness that betrays.

The sad part is that, in this case, it really doesn't matter: you don't understand any of it anyway. A well-turned, singable phrase is just as incomprehensible as an awkward, misac cented one, for these performers, like those Anglican High Churchmen who mumble their ritual English to make it sound like Latin, sing everything to sound as much as possible like Old Norse-or possibly early Anglo-Saxon.

Perhaps the slow tempos are intended to help comprehension, but the effect is exactly op posite: the singers have every opportunity to linger deliciously over endless, Brobdingnagian dipthongs that never existed in any language at all. Another effect of slow tempos is that the singers, believe it or not, are often impatiently pushing ahead of the beat. These problems are most severe in the excruciatingly slow first act; the last two acts show more in the way of vital signs.

The singing is competent but, with one exception, rarely thrilling. The outstanding vocalist is easily Norman Bailey, whose solid and vibrant Wotan has real nobility and tragedy; he is the one performer who takes advantage of the fact that he is singing in his native language with "real" words full of emotional as well as literal meaning to intensify his interpretation. His appearance at the beginning of Act II creates an electricity entirely missing from the first act and even seems to galvanize Goodall.

On the whole, the men fare better than the women. I liked Alberto Remedios, who, in spite of his name (and apparent Latin ancestry) was born in Liverpool. A lyric Siegmund is a pleasant surprise. Now and again, though, one misses the impetuosity and the soaring, transfigured quality that the role demands (it is precisely these qualities that are most lack ing in the performance as a whole).

The recording was taken from live performances at the London Coliseum in December 1975-presumably a montage of the best sections from three evenings. It is an excellent job and (in case you wondered) achieves good balances between the voices and orchestra.

E.S.

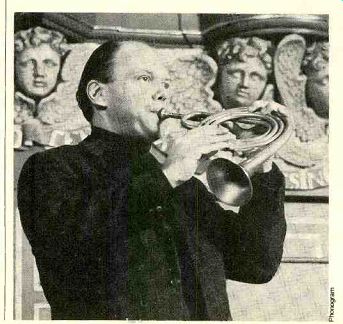

WOLF: Lieder on Poems by Goethe, Heine, and Lenau (see Best of the Month, page 84) COLLECTION DON SMITHERS: The Trumpet Shall Sound.

Purcell: Trumpet Tune, Ayre, and Cibell.

Blow: Vers-Fugue in F Major. Morley: Canzonet La Caccia; Canzonet La Sampogna.

Handel: Concerto in B-Flat Major. Stanley: Trumpet Voluntary in D Major. Fantini: So nata a Due Trombe detta la Guicciardini.

Campion: Never weather-beaten sail. Bull: Variations on the Dutch Chorale "Laet ons met herten reijne." Biber: Suite for Two Clari no Trumpets. Dowland: Lacrimae Pavin, "Flow my tears." Frescobaldi: Capriccio sopra un soggetto. Anon.: Hejnal Krakawska.

Don Smithers (clarino trumpet, piccolo trumpet, cornetto); Clarion Consort. PHILIPS 6500 926 $7.98.

Performance: Excellent

Recording: Excellent

In searching out a repertoire for the trumpet, Don Smithers has boldly availed himself of works originally written for harpsichord, organ, voice, and oboe. Considering that this was customary during the Renaissance and Baroque eras, purists should not indulge themselves in any twentieth-century qualms they might have about transcriptions. The proof of the pudding lies in the musical results, and here there is nothing to quibble about; Don Smithers is just fine both as a technician and as a musician. And the arrangements, relying heavily on organ accompaniment, are tasteful and effective. More important, Mr. Smithers brings them off so skill fully that they sound as though they were conceived for the remarkable variety of trumpets he tackles for this fine disc. S.L.

----- DON SMOTHERS: just fine both as a technician and as

a musician.

---------------------

Head to Head on Beethoven's Nine

The late Rudolph Kempe; Bernard Haitink.

THE age of recording has its own set of qualifications to be met by those aspiring to international musical fame, and interpreting Beethoven convincingly is at the top of the conductors' list. Soon or late, every maestro with an eye on the history books must submit himself to posterity's judgment, in com petition with the others, by putting performances of the nine symphonies onto discs.

The two most recent entrants in this continuing contest approach the music from different backgrounds, different circumstances, and at different points in their careers. Un happily, Seraphim's American release of Rudolf Kempe's version of the complete sym phonies has had to serve as a memorial to the conductor, who died last May at the age of sixty-five. Bernard Haitink's set for Philips, on the other hand, comes in the middle of the forty-seven-year-old conductor's career, and the most surprising thing about it is that he didn't get around to it sooner.

Deciding between these two issues is rather like deciding between a pair of well-made, good-looking shoes and a pair of slightly eccentric but captivating ones that aren't going to last through the winter. First-time purchasers of the Beethoven symphonies have no choice here but to go with Haitink; they may not always be excited, but neither will they be incensed, and in the long run they'll be served very, very well. But adventurous collectors will covet the Kempe set, for the performances are always interesting-at worst annoying, at best fascinating.

The most pervasive problem in the Seraphim set is the orchestra, the Munich Philharmonic, which is simply not up to the competition in today's symphonic arena. Their sound can be harsh and badly blended, their technique unreliable. For every time on these six teen sides that the listener is enchanted by the sound of active playing-that is, by the feel that the instrumentalists are actually bowing, blowing, hitting-there is another when the musical "mechanics" seem to be just that.

Haitink's London Philharmonic is not with out its drawbacks, but it is an able ensemble, ready to meet the conductor's cues with a modern blending of strings and winds and most of the time-with technical élan. Furthermore, the sound on the seven Haitink discs is brighter and clearer. The Kempe set proudly claims the distinction of being the first budget issue of the complete symphonies in compatible SQ/stereo quadraphonic sound, but the four-channel sound is occasionally confusing to the ear (what are the cellos doing sprinting to the back of the hall?), and the benefits even in the effectively engineered passages are minimal.

The only other practical consideration is the sequencing of the music: Kempe uses the Prometheus, Leonore No. 3, and Egmont Overtures as fillers for the Eroica, the Fourth, and the Fifth, respectively, to keep to a policy of one symphony, one record (the First and the Second take one side each). Haitink's set includes only the symphonies; the Second shares a side with the First, and the disc of the Third also accommodates the first movement of the Fourth.

But these considerations should be negligible compared to the issue of interpretation.

Throughout, Haitink is almost defiantly true to Beethoven's written wishes, while Kempe perhaps does what he thinks the composer would have wanted him to. Haitink's sense of lyricism is the more natural, but Kempe discovers the drama more easily and with more flair. Kempe feels free to add his own ritards and accelerandos, and occasionally he has trouble holding a tempo (most notably in the finale of the Seventh). Haitink holds religiously to the pace, avoiding any change that isn't indicated in the score, and sometimes taking those only reluctantly. Both treat repeats arbitrarily, presumably so that the music will fit neatly onto the discs, though in the long run Haitink is both more consistent and more sensible in his decisions.

Haitink's approach is generally less person al, and the one symphony in which this makes the most striking difference is the Third.

Kempe's opening statement is irresistible, with a feeling of anticipation that doesn't settle into sureness and boldness until the thirty seventh bar. Haitink, on the other hand, set in his ways, is solid from the outset. The two conductors negotiate the second movement in exactly the same amount of time, but Kempe's work is more somber and thoughtful, with an attractive growl in the lower strings and a tendency to make the most of the unusual. Haitink's scherzo is lighter than Kempe's; the older conductor likes to plow forward strongly. Kempe's tendency to fool ...

[Soon or late, every maestro must submit to judgment . . . ]

... around with tempos gets just a bit tiresome in the finale, but both versions are basically traditional.

ERNEST NEWMAN'S intelligent notes, originally companions to the Cluytens version, accompany the Seraphim set. The Haitink brochure includes shorter descriptions of the music with a shallow essay having the rather unfortunate title "Beethoven-Man, artist, personality." -Karen Monson

BEETHOVEN: The Nine Symphonies. Overtures: The Creatures of Prometheus; Leonore No. 3; Egmont. Urszula Koszut (soprano); Brigitte Fassbaender (contralto); Nicolai Gedda (tenor); Donald McIntyre (bass); Munich Philharmonic Choir and Munich Motet Choir (in Ninth Symphony). Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, Rudolf Kempe cond. SERAPHIM SIH 6093 eight discs $31.84.

BEETHOVEN: The Nine Symphonies. Hannelore Bode (soprano); Helen Watts (contralto); Horst Laubenthal (tenor); Benjamin Lux on (bass); London Philharmonic Choir (in Ninth Symphony). London Philharmonic Orchestra, Bernard Haitink cond. PHILIPS 6747308 seven discs $58.86.

*Music critic, Chicago Daily News

--------------------------------

-------------------

Weber/Mahler Die Drei Pintos

IN Munich early last year, avowedly to honor the sesquicentennial of Carl Maria von Weber's death, RCA sponsored a first-ever but otherwise unremarkable recording of Die Drei Pintos. Of what? Well may you ask.

During May of 1820 and the first weeks of 1821, Weber sketched some 1,700 measures of musical ideas (in a private shorthand, not to mention in pencil) for seven numbers in a libretto of seventeen such-. Altogether, he orchestrated less than twenty bars. Following his death in 1826, the widow Weber dispatched these fragments to Meyerbeer, her husband's former fellow-student and admiring friend, in the hope that he could decipher them. Twenty-six years later, in response to an ultimatum, he returned them untouched.

Others afterwards disparaged these encoded snippets of Weber as indecipherable, impossible to reconstruct-in a word, hopeless.

Yet the Weber family never gave up hope.

Thus, in time, Die Drei Pintos came into the possession of the comp(' 's grandson Carl, a Saxon army captain who lived with his family in Leipzig. There, in 1886, young Gustav Mahler arrived as second conductor (under Nikisch) at the Stadttheater, with Das Klag ende Lied and the Fahrenden Gesellen songs already in his creative portfolio.

Say for grandson Carl that he could at least sniff out musical talent. He befriended Mahler and plied him with entertainment to insure a new study of the Pintos fragments. (That Mahler fell headlong in love with the captain's wife was an unanticipated and ultimately scandalous by-product of Carl's inherited Webermania.) Although at the time working a double shift at the Opera (owing to Nikisch's illness) and simultaneously composing his First Symphony (inspired by love for Marion von Weber), Mahler cracked Carl Maria's code one spring day in 1887.

With all speed and reverence, the young composer-conductor instrumented the little that Weber had sketched for Die Drei Pintos and proposed its publication in this incomplete form. Carl counter-proposed, backed up by Mahler's boss at the Leipzig Opera, that an entire work be created, using other of grand father Weber's music in the untouched numbers. Mahler finally succumbed to pressure, but only with the proviso that Carl revise the original libretto of 1820 (ne Der Brautkampf).

This involved a juxtaposition of the first and second acts, and the addition of three further musical numbers. Ironically, as viewed in retrospect, the end product that had its world premiere in Leipzig. on January 20, 1888, brought Mahler both his first real fame throughout the Germanies and the first wealth of his life.

By the end of 1889, eight cities had produced Die Drei Pintos, including Vienna (where, however, it was coolly greeted). After a performance (by Mahler at the piano) of the first act in 1888, Richard Strauss praised it out of all proportion in a letter to his Meister, Hans von Billow, only to be rebuked six months later and have to eat crow when Billow damned the work. Critic Eduard Han-

slick was obliged to agree ("weak Weber") in his review of the Leipzig premiere for his Viennese readers-. The performance was also attended by Tchaikovsky ("very nice" music but a "stupid" text, he wrote to his brother Modeste).

On the evidence of RCA's just-released re cording of the work, Tchaikovsky over praised the music. Almost as suddenly as Die Drei Pintos appeared as a comet in the musical firmament, it disappeared. No amount of hyphenated attribution to Mahler, now as then, can be sufficient to rescue Pintos from desuetude. It is simply and irremediably a postdated Singspiel set in Spain (a locale fashionable at the time of Weber's interest, whet ted by Rossini's recent success with II Barbiere di Siviglia), a "numbers" opera with spoken dialogue. The libretto-never a strength even in Weber's echt operas-at best prolongs an anecdote, prosaic as prosodized, doggerel as rhymed. That Mahler's working over of Weber's fragments failed to capitalize on a beery humor in the text further exaggerates the lack of significant characterization.

Die Drei Pintos does not evolve musically (being chiefly strophic or A-B-A in form) any more than it develops dramatically. It is aggregately trivial, albeit now and then pretty.

One must stretch a point to find wisps of Weberian individuality, much less of inspiration, in other than No. 10, a mellifluous recitative and aria for the heroine (one Clarissa of Madrid, whose father Don Pantaleone would wed her to Don Pinto, the bumpkin son of a kindly stranger who once saved his life). With the advantage of hindsight, one can discover Mahler's fingerprints on this concoction about how, in Salamanca, fortune-hunting Don Gas ton and his servant Ambrosio purloin a letter ...

[ It is aggregately trivial, albeit now and then pretty . . . ]

... of introduction to Pantaleone from the "first" Pinto about Gaston's impersonation in Madrid of the groom-to-be (making him the "second" Pinto), and his quitclaim in response to the pleadings of Don Gomez, Clarissa's true love (who becomes the "third" Pinto), before the real rube rushes in, creates a vulgar ruckus, and is sent packing by a bewildered but wiser Pantaleone.

Even during the first hearing, one doubts that a more flexible and fun-seeking conduc tor than Gary Bertini would be able to dis guise the commonplace nature of Weber's sketches, or the hesitancy of Mahler.to foliate them fully. A chorus from the Netherlands in this recording sounds perfunctory although not effortful; virtually- the same may be said about members of the Munich Philharmonic.

Bertini's cast of eight sings efficiently from unchanging stations in a brewing-cellar with acoustics both hollow and muffled. The participants in solo roles ascend in vocal charm from the gusty, rhythmically square mezzo soprano of Kari Levaas (as Clarissa's obligatory maid, seen, wooed, and won instanter by Ambrosio) to the prime-time effulgence of Kurt Moll's basso cantante (as the rightful Pinto).

What remains provocative after a few hearings of Die Drei Pintos is the influence upon Strauss' music for Baron Ochs, in Der Rosen kavalier, of Weber-Mahler's bumpkin Don and Mahler's own interlude between the first and second acts depicting a drunken Don Pinto's dream-this near to, in quality, although less developed than, the Biumine later excised from the First Symphony.

RCA has lavished six disc sides on just one hour and forty-two minutes of music, plus fourteen minutes more of spoken-dialogue.

This averages out to a short twenty minutes per side, in spite of which, at decibel levels louder than a modest mezzo-forte, three different elliptical styli-top-of-the line Supex, Shure, and B&O-persistently buzzed on two stereo playback systems. Only Grado's F-1+ (intended for CD-4 discs) took these Hamburg pressings in stride, except for the brouhaha that begins Act III. The discs are otherwise. (considering their European source) untypically thin, with a low-bass rumble, ticks and pops, and static properties that need several zappings with a Zerostat, per side, to tame each time through.

Notes by Franz Willnauer on the back ground, completion, and plot of Die Drei Pintos, in a black-and-white presentation book let, have been translated trilingually (which is not to say always accurately); however, the text itself is printed only in German-not that you'll miss any pearls of nuance if that language shouldn't be in your repertoire.

-Roger C. Dettmer

WEBER/MAHLER: Die Drei Pintos. Lucia. Popp (soprano), Clarissa; Jeanette Scovotti (soprano), Inez; Kari Leivaas (mezzo soprano), Laura; Werner Hollweg (tenor), Don Gaston; Heinz Kruse (tenor), Don Gomez, Majordomo; Hermann. Prey (baritone), Ambrosio; Kurt Moll (bass), Don Pin to; Franz Grundheber (bass), Don Pantale one, Innkeeper. Netherlands Vocal Ensemble and Munich Philharmonic, Gary Bertini cond. RCA PRL3-9063 three discs $23.94.

-----

------

Also see:

MAKING THE CASE FOR ELGAR--He was, after all, the first composer to take the phonograph seriously, BERNARD JACOBSON

BEST RECORDINGS of the MONTH (Mar. 1977)