by JAMES GOODFRIEND

RECORDS AT THE DOOR

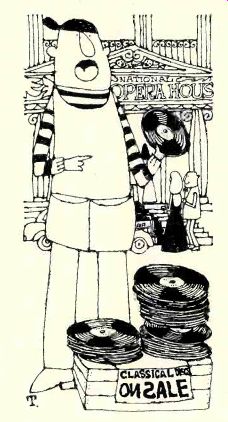

DID you ever wonder why, when statistics tell us that more people in this country attend musical events than attend sporting events, so few classical records get sold? I've wondered. Lots of people I know have wondered. And the answer always seems to come up the same: the records aren't there to be bought.

The kicker in that statement--inflammatory as it might seem to some people--is just what do you mean by "there?" If "there" is the Schwann Catalog or the warehouses of the record companies, the records, by and large, are there. If "there" center, the records are also, for the most part, around to be purchased. But if "there" is al most any place else, it's no cigar. I don't mean that you can't buy a classical record in Kansas City, but you may not be able to buy the one you want. And there are all too many places in this land where record stores do not stock classical music and many others where you can't even find a record store. Record companies tend to write off such places as no market, but that isn't necessarily true. Ac cording to the 1976 Target Group Index, a consumer research study prepared by Axiom Market Research Bureau, there are 9,344,000 adult listeners in the United States who, on the "average day," prefer to tune their radios to classical music over anything else. They don't all live in the hundred or so cities with classical record stores. They don't even all necessarily know where the nearest classical record store is.

Record clubs and mail-order companies in general have proved to be only a partial answer to the problem. Forgetting about the limited selection offered and the attendant problems of ordering, paying for, and receiving mail-order merchandise, the purchasing satisfaction is simply not the same. The greatest enticement to the purchase of a record is the physical presence of the record. The greatest satisfaction to the desire for a particular record is to be able to buy it then and there.

When is then? Where is there? There are a number of different answers to those questions, but a very important answer to the first of them is "immediately after a concert." And an equally important answer to the second is "at the concert hall." The pianist Tedd Joselson is an incredibly busy young man. He makes a large number of appearances each year with both major and minor orchestras. He records regularly for a major company (RCA). He also plays numerous solo recitals all around the United States and draws large audiences in areas where you might not think there was a large audience.

He has achieved considerable success with out compromising himself or his musically serious repertoire. But when he plays a Prokofiev sonata in, say, Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin, or Orange City, Iowa, he finds one question waiting for him, time and time again, from the people who come to greet him back stage afterwards: "Where can I buy your records?" That is an irritating question for an artist, particularly one who records for a major label.

Well, suppose they could buy them then and there, right out front in the concert hall.

How many people do you suppose would? Joselson, busy as he is with other things, decided to find out. He played a recital in Atlantic City, New Jersey, a smallish affair with an audience of six hundred. He arranged for his records to be on sale at the concert hall, particularly the records of what he was playing that evening. Eighty discs were sold. He tried again in Huntington, Long Island, a far less promising location because of its proximity to New York City and the major discount stores.

An audience of three hundred purchased twenty-nine discs. Extrapolation from those examples is all too easy. If we assume that Joselson plays for a hundred thousand people a year (and that's probably not out of line), his record sales should be somewhere between ten and fifteen thousand. What is even more important is that most of those sales would be in addition to sales made through normal distribution channels. Why? Because these are the people who ask, "Where can I buy your records?" and, hardly ever receiving an answer that permits of immediate, straightforward, and simple action, who do nothing further about the matter.

Selling records at concerts is, on the surface of it, an absurdly simple matter. But it becomes incredibly complex when the number of different artists or ensembles increases.

With , say, one hundred different recording artists, each playing, say, fifty concerts a year, one has five thousand events, or an average of almost fourteen per day, to, for, and at which records must be sent, selling arrangements made, money collected, books kept, sales tax computed and paid, and unsold merchandise recovered and returned. That is the kind of operation no record company is equipped to handle today, nor is it likely that many would care to equip themselves for it. And yet a reasonable estimate of the record sales that would accrue from it is about five million which is enough to put an end to the "classical crisis" once and for all for any company benefiting from such additional sales.

That it would also benefit the artists goes without saying: extra income and extra expo sure without playing a single additional recital or a single additional recording session. That it also benefits the confirmed collector of classical records is a little less obvious, but also true. A healthy, profitable industry offers the best potential for the long-term satisfaction of all his discographic desires.

A NEW company has been organized to set up this sort of record marketing. It is called Concert Discount Records and is run by a Mrs. Debora Low. (Requests for information sent to me-in care of STEREO REVIEW, One Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016--will be forwarded to her.) Mrs. Low plans to start on a small scale, but if the results achieved are anything like those logically projected, a lot of people who have never cared to put much effort into obtaining a classical record may find themselves serviced with exactly the record they want at the time they want it. The fact is that in terms of the considerable sums of money Americans spend today on leisure-time activities and associated expenses (cabs, dinner, parking, etc.) the cost of a classical record is small, and in terms of value received it is an almost unmatched bargain. If it can be made to be "there" when someone wants it, it should prove far more salable than it has in the past.

---

Also see: THE POP BEAT; PAULETTE WEISS