ROOTS OF JAZZ--Amazingly, some of the artists who started it all are still around. CHIRIS ALBERTSON.

By Chris Albertson

-------

Amazingly, some of the artists who started it all are still around, offering living proof that jazz is not as ancient an art form as our ears might lead us to believe

------------

ROOTS...

Selected Discography

EUBIE BLAKE: Rags to Classics. Eubie Blake (piano). Charleston Rag (1921 and 1971 versions); Capricious Harlem; Rustles of Spring; You're Lucky to Me; You Do Something to Me; Rain Drops; Pork and Beans; Valse Marion; Classical Rag; Scarf Dance; Butterfly; Junk Man Rag. Eu BIE BLAKE MUSIC EBM-2 $6.95 (from Eubie Blake Music, 284-A Stuyvesant Avenue, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11221).

SISSLE AND BLAKE: Rare Early Recordings, Vol. 1. Noble Sissle (vocals); Eubie Blake (piano, vocals). Baltimore Buzz; Love Will Find a Way; I'm Craving for That Kind of Love; Bandana Days; Pickaninny Shoes; Broadway Blues; I've Got the Blues; I've Got the Red, White, and Blues; I'm a Doggone Struttin' Fool; Boo Hoo Hoo; Down Hearted Blues; Waitin' for the Evenin' Mail; Sweet Henry.

EUBIE BLAKE MU SIC OO EBM-4 $6.95.

SAM WOODING: Sam Wooding and His Chocolate Dandies [sic]. Sam Wooding and His Chocolate Kiddies Orchestra. 0 Katharina; Shanghai Shuffle; Alabamy Bound (two takes);

By the Waters of Minnetonka; I Can't Give You Anything but Love; Bull Foot Stomp; Carrie; Tiger Rag; Sweet Black Blues; Indian Love; Ready for the River; Mammy's Prayer; My Pal Called Sal; Krazy Kat; I Got Rhythm. B10-GRAPH BLP-12025 $6.98.

SAM WOODING/RAE HARRISON ORCHESTRA: Bicentennial Jazz Vistas. Sam Wooding and His Orchestra (instrumentals); Rae Harrison (vocals).

Sam's Jam; Either You Do, or Else You Don't; Blah Blah; Funky Joe; Love Is Just a Pretty Thing; Echoes of the Republic. TWIN SIGN TS-1000A $5.95 (from Twin Sign Records, P.O. Box 713, Radio City Station, New York, N.Y. 10019).

JACK JACKSON: Jack Jackson and His Orchestra. Jack Jackson and His Orchestra (instrumentals); Alberta Hunter (vocals). Make Those People Sway; I'm Playing with Fire; Long May We Love; I Travel Alone; Come On, Be Happy; Miss Otis Regrets; I'm Gettin' Sentimental Over You; Two Cigarettes in the Dark; Dixie Lee; Two Little Flies on a Lump of Sugar; Settin' in the Dark; What a Little Moonlight Can Do; Stars Fell on Alabama; Blue River, Roll On; Be Still, My Heart; Let Bygones Be Bygones. WORLD RECORDS 0 SH 210 $6.98 (British label, avail able at stores dealing in direct imports).

-----------

ITS roots run deep and wide, its branches have touched virtually all twentieth-century music, and some how it seems as if JAZZ has been with us longer than anyone can remember.

That is, of course, partly because of electrical recording technology, which only fifty years ago began making the earlier acoustical jazz discs appear as primitive as the Wright Brothers' plane. But even more misleading is the music itself, for jazz has over the years taken on a sound so radically different from its earliest forms that many critics and musicians-with some justification-feel that the term no longer covers the music.

The turning point was bebop-the first so-called "modern" jazz-which emerged in the early Forties and immediately produced a cry of "foul" from the traditionalists, some of whom had yet to accept fully the swing style of the Thirties. As World War II ended, a jazz war was declared: "Hot versus Cool" band battles were staged on records, on the radio, and in clubs by enterprising critics and producers who saw commercial value in the conflict.

But the polemicists eventually tired, and by the late Fifties, when Ornette Coleman entered the jazz arena, most people had agreed that old and new jazz could lead a healthy coexistence.

Coleman's music-a free-form style that disregarded chord changes and a regular beat-made bop (as it was now called) sound conventional by comparison, and, as this natural evolution has continued, some of today's music makes even Coleman's music of eighteen years ago seem amazingly accessible. It can be argued, as before, that some improvised music-such as that fostered by Chicago's outre AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Music)-just isn't, strictly speaking, jazz. That particular music certainly is a far cry from the music originally named jazz, but no one can deny that even this "new music" at least has its roots in the works of the early jazz pioneers.

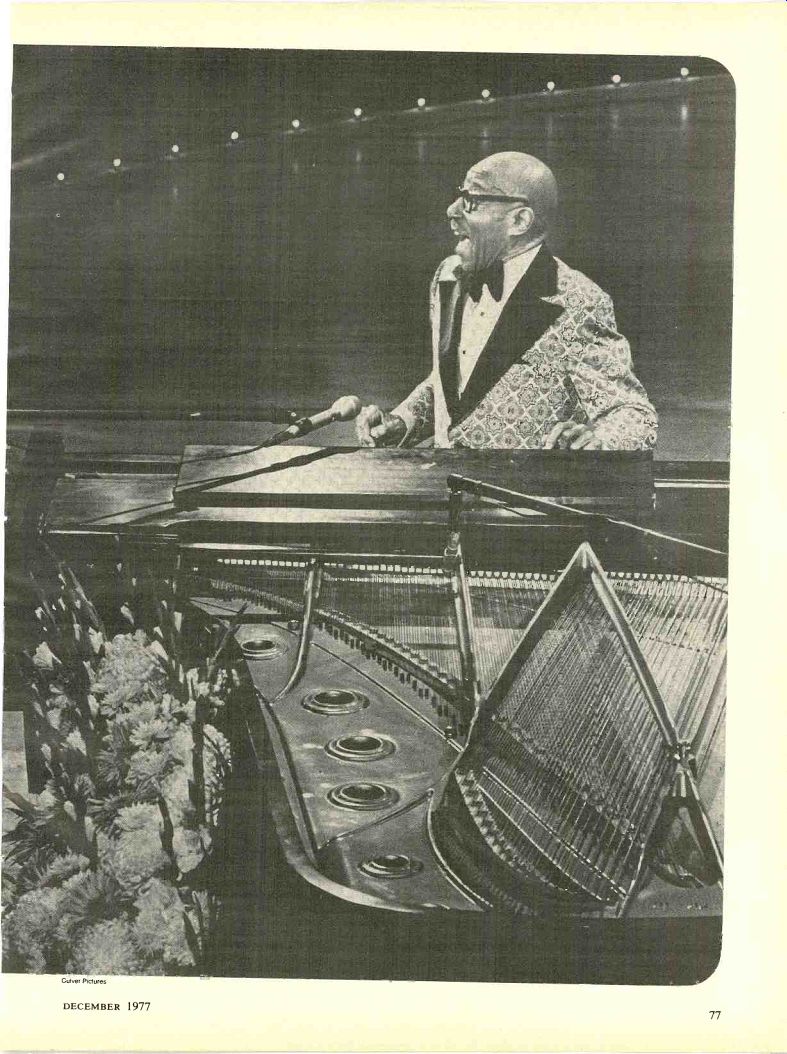

Amazingly, some of the artists who started it all are still around, offering living proof that jazz is not as ancient an art form as our ears might lead us to believe. More to the point, some of these survivors-and that is an apt term when one considers the rigors a life in jazz has traditionally entailed are not only alive and well but still per forming. Best known, and probably the oldest of these almost legendary stalwarts, is the composer/pianist Eubie Blake, who this February will be celebrating his ninety-fifth birthday. A frequent guest on TV's Tonight show.

Blake was composing rags and playing them in Baltimore sporting houses before the turn of the century. In 1921, Blake and his long-time partner, the late Noble Sissle, co-produced and wrote the music for Shuffle Along, a black musical that was a smash success and pointed the way for Broadway productions to follow. One of its hits, I'm Just Wild About Harry, was to become Harry S. Truman's campaign song twenty-seven years later, and its star, Florence Mills, became one of the most beloved figures in the black entertainment world before her premature death in 1927.

Eubie Blake himself, a slender man of great wit and remarkable agility, was at his peak fifty-five years ago, but to see him perform today-charming his audience with humorous reminiscences and racing his nimble fingers across the keyboard to produce rags he wrote be fore our parents or grandparents were born-one would never guess it. A tire less traveler, Mr. Blake-who is man aged by his "eightyish" wife, Mar ion-spent three weeks performing in Oslo and Copenhagen this past sum mer. He has been booked for the New Orleans Jazz Heritage Festival this coming April, and has also just received an offer to give concerts in Australia. Will he go? But of course.

At eighty-two, singer Alberta Hunter and bandleader/pianist Sam Wooding are not far behind Mr. Blake; they too began performing in the jazz idiom be fore the term was coined, and they share with their older colleague the belief that retirement is analogous to doom. "I have worked all my life," says Miss Hunter, who became a nurse when she first left the entertainment field twenty years ago, "and I just can't see sitting around doing nothing and talking about one's yesterdays." Mr. Wooding concurs: "My love affair with music has been going on for too long, and it's too deep for me to even consider breaking it off now. This business of retiring at sixty-five is plain nonsense back will make you an old man, and who wants to be an old man?" IT was to help her mother, who was born into slavery, that Alberta Hunter left her Memphis home around 1909 and ran off to Chicago. "I used to sing in school, and they told me I was pretty good," she recalls, "so, when I heard that girls were making ten dollars a week singing in Chicago joints, I decided to catch a northbound train and make some money for my mother." On the day of her arrival, an extraordinary stroke of luck put her in touch with an old family friend. "It must have been fate," she says, "because I had no idea where this woman lived. I was so naïve that I thought all you had to do was to go to Chicago and ask around. Well, I walked into this office building and asked this cleaning woman if she knew where my friend lived. Don't you know, she was able to take me right to her. God was putting his arms around me." With her friend's help, little Alberta was soon earning her room and board peeling potatoes and washing dishes for a boarding house, but she hadn't lost sight of her goal. Adding a few Young pianist/composer Eubie Blake appeared with the Boston Pops last year.

years to her appearance with a new hairdo and a dress borrowed from an older woman, she spent her nights making her singing talent known to club owners on the South Side. Soon she was singing at Dago Frank's, a gathering place for white hookers, who were known to brush tears from their eyes as little Alberta poured her Memphis soul into such popular fare of the day as Where the River Shannon Flows.

At first she knew only two songs, but she made it a point to learn a new one every night until she had built up a good, varied repertoire.

WILE Alberta Hunter was using Chicago's South Side dives as a training ground, Sam Wooding had moved from Philadelphia to Atlantic City, where he made his living performing under most unusual circumstances.

"They used to call us pianists ‘professors,' he recalled recently, "and we would hang out on a street corner until one of the working girls in the area sent her maid to get one of us. The girl would have a client in her room, and a screen separated her bed from the piano. It was our job to accompany them as they made love. Through a crack in the screen, we were able to follow their action and provide the appropriate sensuous music. Naturally, as they worked themselves up, I brought the music to a sort of crescendo. It was interesting-like playing for a silent movie." Mr. Wooding's next job offered a change of pace; he traveled to Europe as a member of Lt. Will Vodery's 807th Pioneer Infantry Band.

In 1919, Wooding, once again a civilian, formed his first band. That same year, Alberta Hunter-having graduated from Chicago's Deluxe Cafe and Panama Club (where one of her co workers was Florence Mills)-became a featured artist at the Dreamland Cafe, the finest of Chicago's many black cabarets. "Her salary was only $17.50 a week," recalled the late Lil Armstrong, who often served as Miss Hunter's piano accompanist, "but she made three to four hundred dollars a night in tips, and when they boosted her salary to $35 a week, we jokingly called her the highest-paid performer in Chicago. She wore heavily beaded dresses that glittered and sparkled as she shimmied around the room and sang. Every now and then she'd make her breasts jump, and then the cats re ally loosened up on their bankrolls." New songs were always being introduced at the Dreamland, a feature that attracted some of the most famous white performers of the day. "They said they were seeking inspiration," Lil Armstrong remarked, "but actually they were only stealing our material.

That's how Sophie Tucker got most of her stuff. She `borrowed' Alberta's songs as well as her style. However, we were making so much money at the time that we really didn't care." As the Roaring Twenties began and Prohibition went into effect, both Miss Hunter and Mr. Wooding found their way to New York City, he with his band at Barron's in Harlem, she to launch what would turn out to be a prolific recording career. The first Alberta Hunter records were made for W. C. Handy's Black Swan label, which boasted in its advertisements that it was "The only genuinely colored record-others are only passing." But a couple of months later she moved to Paramount Records (a subsidiary of the Wisconsin Chair Company), where she recorded her own Down Hearted Blues.

It was a big hit, but it did even better for Bessie Smith, who recorded it on her first Columbia session and saw it sell some 800,000 copies.

By the summer of 1929, Miss Hunter had also graced the studios of Okeh, Victor, and Vocalion, recording over seventy-five sides with accompaniment by such outstanding artists as King Oliver, Fletcher Henderson, Fats Waller, and Louis Armstrong-not to mention her two fellow "survivors," Eubie Blake and Sam Wooding. She had also starred in a couple of Broadway shows, headlined in some of New York's biggest black-oriented night clubs, and, as she puts it, "made a pile of money" enough to take a well-earned vacation in Monte Carlo.

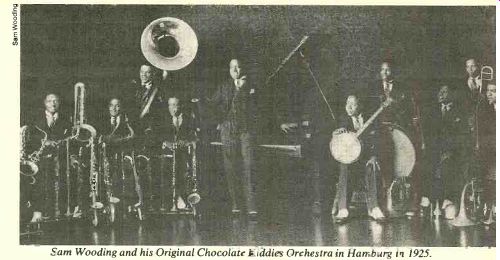

SAM WOODING hadn't done so badly either. In 1925, while his band was en gaged at the famous Club Alabam (where it had replaced the Fletcher Henderson Band), his unusual arrangements caught the ear of a famous Russian impresario. Dr. Leoni Leonidof, whose clients included Feodor Chaliapin and George Balanchine, had come to the U.S. to recruit a black show for a European tour. Arthur Lyons, a well known American theatrical agent of the day, brought Leonidof to the Alabam, and the Wooding orchestra was hired on the spot. "The show was called The Chocolate Kiddies because we saw a billboard advertising a chocolate by that name when we got to Germany," Wooding recalls, "but it wasn't a scripted, story-telling show, just a bunch of acts put together." They opened at Berlin's Admirals Palast on May 6, 1925, an assemblage of forty musicians, dancers, singers, and jugglers. It was a premiere Sam Wooding will never forget: "We had picked By the Waters of Minnetonka as our overture, and we really played it that night, but instead of the immediate applause we were used to there was a stillness when we finished. Then, like a clap of thunder, the audience started banging their feet and shouting 'Bis nochmal hoch, bravo,' and the din was so great that `Ns' ['morel sounded like `beast' to us and some of the boys were about to run out of the orchestra pit be fore we realized that they were being complimentary." The show created a sensation, and it gave many music critics their first taste of a live jazz orchestra. From Berlin, the Chocolate Kiddies revue moved on to Hamburg's Thalia Theater and Copenhagen's Cirkus. The reviews were uniformly enthusiastic, if somewhat confused: "It's something completely insane, fantastic, incomprehensible," wrote a bewildered Danish critic. "The black musicians toil so that only the whites of their eyes are showing, while Sam Wooding, quite aloof, waves his white stick and conducts with serious ness and reverence, as if a symphony were being performed. It is the wildest cacophony. One is angered, insulted, and ready to tear one's hair out. But listen! Out of this confused noise there rises a tone so clear and fine that it fills the ear with joy. Why, it's Tannhailser!" And indeed it was. Sam Wooding was fond of presenting what he called "a syncopated synthesis" of the classics. "Du holder Abendstern syncopated!" continued the reviewer. "It's sheer blasphemy-and yet, out of all this mess one hears the most beautiful harmonies, the clearest tones. They are musicians, after all, and they know their stuff. It's not the monotonous pling-plang of the East. It's premeditated rape of the ears. . . . Intoxicated, anesthetized, and overwhelmed, one stumbles out of the theater." The rest of the show received equally enthusiastic reviews, prompting some of the acts to leave the show early and go out on their own. A replacement for one such deserter was a young English lady named Mabel Mercer.

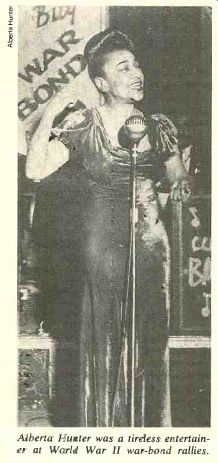

------------- Alberta Hunter was a tireless- entertainer at World War II war-bond rallies.

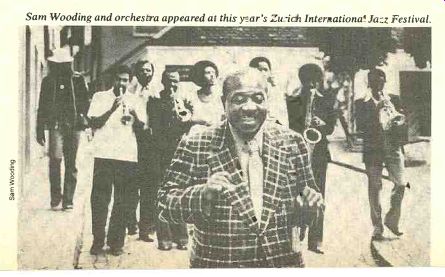

---------- Sam Wooding and orchestra appeared at this year's Zurich International Jazz Festival.

----- Sam Wooding and his Original Chocolate Kiddies Orchestra in Harrburg in 1925.

AFTER the breakup of the Chocolate Kiddies, Wooding decided to stay in Europe with his band. They played all over the Continent, visited Moscow and Leningrad (decades before Benny Goodman's allegedly pioneering trip there in the Sixties), and even took a "side trip" to South America via Africa. In 1925, the band made a series of recordings for Vox in Berlin (thus becoming the first black American band to record outside of the U.S.), followed, in 1926, by a series for the German Polydor label, ten imaginative sides recorded for Parlophone in Barcelona in 1929, and numerous Paris sesions for Patine and Polydor.

While Wooding spread his jazz to different parts of the world, Alberta Hunter, still vacationing in Monte Carlo, received a telegram from Noble Sissle suggesting that she make a stop over in London to perform at a much-heralded, star-studded, flood-relief benefit. "I jumped at the chance," she recalls, "because I had wanted to per form in England but couldn't get the required work permit." As luck would have it, the benefit was attended by Os car Hammerstein II and Jerome Kern, who obviously liked what they heard.

"I was staying with Marion Anderson, and Mr. Hammerstein called me there the next day, asking me to come down to the Drury Lane Theatre. Next thing I knew I had the part of Queenie in the London production of Show Boat, which had a wonderful cast, including Paul Robeson, Edith Day, and Sir Cedric Hardwicke."

JAZZ ROOTS...

"It was my first appearance in Zurich in fifty-two years. It never hurts to make yourself a little scarce."

The Kern/Hammerstein musical finished its one-year run at the Drury Lane, and Miss Hunter literally began commuting between New York and various European capitals. Showing her versatility, she became a sultry, sophisticated ballad singer when she re corded and performed, at the posh Dorchester Hotel, with Jack Jackson's Orchestra in the fall of 1934, adding to her growing coterie of fans the Prince of Wales and Noel Coward. Her elaborate cabaret act, which featured a white chorus of feathered girls perched on a bar inside a giant birdcage, was a huge success from the Casino de Paris to Copenhagen's National Scala.

Also in 1934, Miss Hunter made history by appearing in the first English film to feature color, Radio Parade of 1935. Formulated after Hollywood's Big Broadcast films, its plot was de signed to showcase some of England's favorite variety artists, and the color-a new and ill-fated process called Dufay color-was seen only in the film's last segment, when Miss Hunter sang a negro spiritual. "I don't know if the film was shown here at home," she says, "but I was getting so much publicity in Europe, and that made the people at home appreciate me more." In 1937 NBC signed her up to do broad casts from New York and-via transatlantic cable-London. In 1939, while appearing in a dramatic role in Mamba's Daughters with Ethel Waters at New York's Empire Theatre, Miss Hunter also made her television debut with NBC and, reverting to the blues, was reunited with Lil Armstrong for a record session at Decca.

SAM WOODING had returned to the U.S. in 1935. "With Hitler on the loose, things were getting too hot over there," he recalls, "and one of our fans, who turned out to be a Gestapo man, knew what was brewing. So he told my agent 'Get Sam out of here be fore it's too late.' " Finding American audiences less receptive, and, one sup poses, the competition stiffer, Wooding disbanded his orchestra the following year; four decades would pass before he formed his next big band.

While studying at the University of Pennsylvania for his bachelor's and master's degrees, he led his own South land Spiritual Choir, a group partly inspired by the Cossack choirs he had heard in Russia. "We were about to de part on a world tour, sponsored by the International Baptist Association in London, when World War II broke out," he recalls, "so we just toured the U.S. and Canada instead." Wooding entered the Fifties teaching music.

Among his students (at Wilmington High School, Delaware) was a young man named Clifford Brown, who, be fore his premature death in 1956, point ed the jazz trumpet in a new direction.

"There was another trumpeter in my class," muses Wooding, "and he was really much better. I suppose he's driving a truck now." Alberta Hunter spent the war and postwar years entertaining troops from Burma to Berlin. She toured the U.S.

and Canada in the early Fifties, worked with Eartha Kitt in the 1954 Broadway production of Mrs. Patterson, and re tired from show business in 1956. "I made no big fuss over it, I just quit.

The Lord had blessed me with a wonderful life, and I decided to do some thing that would help others, so I studied nursing." Miss Hunter's only musical activity over the past twenty-one years has been to record two albums (in 1961, for the Prestige and Riverside la bels), but, as this issue goes to print, that has begun to change. Earlier this year, after twenty years of service, Alberta Hunter left her job at New York's Goldwater Memorial Hospital and returned to her first love: music.

Barney Josephson, whose Café Society clubs featured some of the greatest talent around during the swing era, booked her to open at his Greenwich Village supper club, the Cookery, this past October. As of this writing at least two major magazines, Newsweek and the New Yorker, are planning feature stories on Miss Hunter's return, the Today show has booked her, and producer John Hammond has plans to re cord her.

STRANGELY enough, though their paths have often crossed, Alberta Hunter and Sam Wooding have not seen each other in over forty years. But don't be surprised if you see them sharing a billing in the future, for Wooding is back in full swing too. His new eleven-piece band, the Sam Wooding and Rae Harrison Orchestra, made a triumphant appearance at the Zurich Inter national Jazz Festival last September, and returned home for a tour of the southern states later that same month.

"They loved us in Zurich," Wooding beamed upon his return, "and they were even more enthusiastic this time around. I suppose that's because I brought over a fresh band of young musicians whose solos they hadn't heard before. It was my first appearance in Zurich in fifty-two years," he added with a smile. "It never hurts to make yourself a little scarce." Who said jazz was old?

---------------

JAZZ FLOWERS...

IN the early Sixties, long before RCA Victor threw its recently retrieved lit tle dog into the garbage can, an executive of the company told me about a computer that determined when an al bum or a single was to be discontinued.

Ruthless and alarmingly indiscriminate, this electronic decision-maker regularly removed from the RCA catalog some of its most meritorious items. "It rejects the Star Spangled Banner regularly," the executive confided, "but the company wants to maintain it in the catalog, so every three months they program it back in." Unfortunately, the national an them-which, from a strictly musical standpoint, we probably all could do without-was (is?) a fairly isolated case; most records simply disappeared before the public had a chance to discover their existence.

The case of LPM-1372 was also an isolated one, but it proved that the wisdom of RCA's computer could successfully be challenged by a member of the record-buying public. The unavailability of this fine recording by the Jazz Workshop (a George Russell group) so upset pianist/composer Ran Blake that he launched a one-man crusade to have it reissued. It was in 1960 that Blake-then a waiter at the Jazz Gallery in Greenwich Village began circulating a petition calling for the reinstatement of LPM-1372; by the time I added my signature there were several pages filled with autographs of the day's most significant jazz performers, producers, and writers. It was an imposing document, and it served its purpose. "At our next a-&-r meeting," recalled my informed RCA source, "we decided to reissue the album, and some one suggested using the signatures for the new cover, an idea that went over well until it was pointed out that we couldn't very well admit it took a petition to get us to release a good album." Thus LPM-1372 finally re-emerged as LPM-2534-but try to find it today. Ran Blake, now chairman of the New Eng land Conservatory's Third Stream Department, later recorded for RCA him self, and, yes, his album has also long since fallen victim to the computer's axe.

DON'T know whether RCA's records are still at the mercy of an electronic brain, but if a browse through your local record dealer's bins reveals such LP oldies as Victor Borge's "Comedy in Music," the Hi-Los' "Love Nest," or the Paul Robeson/Uta Hagen/Jose Ferrer recording of Othello, don't think you've discovered a computer error they're on the Columbia label and they're part of a reissue program that is one of the best-kept secrets in the record business. Since 1970, the Special Prod ucts division of Columbia Records has quietly (because they have no advertising budget) and with some regularity selected "the most sought-after albums from the archives of Columbia Records" and restored them to the catalog in a "Collectors' Series" that now numbers over 250 albums.

MOST sought-after" is a little mis leading, for many of the resurrected items are, in fact, quite esoteric; one can, for example, hardly imagine a big market for "An Evening with Alistair Cooke at the Piano" (AML4970) or "Bantu Music of East Africa" (91A02017). But on the other hand, 91 B02058, a two-record set of heartbeats (mono only) is reported to be doing quite well in medical circles. Also doing well are soundtrack and original-cast albums and many of the catalog's resurrected Masterworks discs, which range from Vivaldi to Imbrie. In the area of jazz (yes, Columbia used to record honest-to-goodness jazz!) there are now over sixty albums in the Collectors' Series, including some recently known to have commanded five to ten times their original price on the out-of-print market.

Among the more outstanding jazz al bums thus brought back are: "Ellington Jazz Party" (JCS8127), a spirited meeting of the Ellington orchestra with Dizzy Gillespie, Jimmy Rushing, and nine tim from the symphonic world; "The Sound of Jazz" (JCL1098), the Count Basie Band, Billie Holiday, the Jimmy Giuffre Trio, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Jimmy Rushing, and Henry "Red" Allen, among others, per forming the music heard on the 1957 TV show of the same name, a show that re mains, visually as well as aurally, the quintessence of American TV jazz presentations; "Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy" (JCL591), 1954 recordings containing some of the trumpeter's finest '

' post-war performances; "Paris Con cert" (JLA16009), featuring the 1958 edition of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, with Lee Morgan and Bobby Timmons; and "Facets" (JP13811), an album of Miles Davis recordings made between 1955 and 1962 and compiled especially for this release.

FOR those wishing to dig even deeper into the jazz past, "The Sound of New Orleans Jazz-1917-1947" (JC3L30, three discs, $17.94) and "Swing Street" (JSN6042, four discs, $23.92) combine rare and well-known recordings to form fine anthologies of how it all began and developed, while "Stringing the Blues" (JC2L24, two discs, $11.96) offers thirty two 1927-1932 sides by violinist Joe Venuti and guitarists Eddie Lang and Lonnie Johnson with all-star supporting casts. The Collectors' Series has a list price of $6.98 per single album. A full catalog, listing dealers in your area, can be obtained from Columbia Special Products, 51 West 52nd Street, New York, N.Y. 10019.

In 1976 Columbia initiated the "Encore Collection," a $4.98 series (also available on eight-track cartridges at $5.98) featuring items that were popular in the Sixties. 'The albums preserve the original cover art and liner notes. Thirty new releases in this series are due to start appearing this month. Unlike the twelve original Encore releases, they will retail for $7.98 (for records, eight-

track, and cassettes) and will be new compilations including many items not previously available on LP's. Though details of the new releases are not avail able at this writing, they will probably bear some kinship to the series' biggest sellers so far.

Topping that list is "Johnny Mathis: A New Sound in Popular Song" (EN 13089, ENA 13089), the singer's re cording debut, made over twenty years ago with various 'orchestras. Among the musicians are Buck Clayton, Art Farmer, Phil Woods, and Hank Jones; among the arrangers are John Lewis, Manny Al bam, and Gil Evans. The voice, though unmistakably that of Mathis, hasn't the tone quality he later developed, but no one concerned need feel bad about this reissue, and the arrangements make good use of the talent on hand. The second-best-selling item in the Encore series is an equally mellow 1970 outing called "Sarah Vaughan in Hi-Fi" (EN 13084, ENA 13084), featuring the Di vine One with an eight-piece Jimmy Jones band including Miles Davis, Benny Green, and Budd Johnson. Sarah too has sounded better since, but she is wonderful here all the same, and the accompaniment is, of course, choice.

OF richly violined, romantic love ballads perceptively sung are your cup of tea, you will welcome back "That's All" (EN 13090, ENA 13090), which represents the early Sixties Columbia debut of Mel Torme. There was more velvet than fog in Torme's voice at that is as enduring as the songs he sings. Trailing behind Torme in sales is "Johnnie Ray's Greatest Hits" (EN 13086, C.) ENA 13086).

They're all there just as he originally cried them, selling neck-to-neck with an unusual meeting, which actually never took place, between Rosemary Clooney and the Duke Ellington Orchestra. "Blue Rose- (EN 13085, ENA 13085) was recorded by Ellington's orchestra and Clooney on separate occasions in 1957, before multiple tracking, made such trickery common practice. The result obviously lacks any kind of rapport between singer and orchestra, and it does justice to neither. Ellington, however,went on to record some very fine albums for Columbia, such as "Hi-Fi Ellington Uptown," "A Drum Is a Woman," and "Such Sweet Thunder," all of which-as CCL830, JCL951, and JCL1033, respectively-are back by way of the Collectors' Series. 'Other Encore albums feature the Hollies, polkas by Frankie Yankovic, Gary Ptickett's soft rock of the late Sixties, stringy MOR sets by Kostelanetz and Percy Faith, a Harry James set with Rosemary Clooney, and, for older feet, some pre-disco dance music by the Les Elgart Orchestra. Future plans call for a generous amount of good jazz in the Collectors' Series, from that distant past when Columbia was less chart-conscious.

-Chris Albertson

------

-----------

++++++++++++++

Also see: New Hope for TV sound

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)