RECORD of the YEAR AWARDS--1977: STEREO REVIEW'S critics and editors select the industry's top artistic achievements.

STEREO REVIEW 1977 record awards and honorable mentions in recognition of significant contributions to the arts of music and recording during the1977 publishing year.

OVER the years-and this is the eleventh of them-of selecting and recognizing outstanding records, we have discovered some built-in characteristics of our method of choosing. Primary among them has been our habit-although it was not planned that way-of anticipating the marketplace, of banking our awards, especially in the pop field, as much on the future as on the present. Let me explain.

As stated often in the past. the STEREO REVIEW awards and honorable mentions are given for musical and technical excellence, for genuine contributions to the recorded literature. They have no basis in sales or commercial success of any sort. Since the awards are for artistic quality, they tend to go to those records that first show that quality in their respective artists-in other words, to the artists who have not yet made it big IDA who are very likely to do so in the near future. The marketplace catches up shortly afterward.

For example, you may remember that we gave awards to John Denver way back in 1970, to Carly Simon in 1971, and to Joni Mitchell on several occasions beginning in 1969. The records we honored may not have been their biggest hits, but they were artistically worthy efforts and the big hits MI owed as naturally as day follows dawning. Just to prove, though, that we are talking about art and no: merely early harbingers of commercial success, I have to point out that a big winner in 1968 was Van Dyke Parks' "Song Cycle." a now-legendary record whose quality is exceeded only by its lack of sales over the years.

The foregoing should help explain why particularly fine records by Joni Mitchell, the McGarrigle Sisters, Emmylou Harris, Linda Ronstadt, and Southside Johnny and the As bury Jukes have not been honored this year. Several of these artists won awards just last year, and all have been honored previously.

The real purpose of the awards is to call attention to excellence, and that attention has al ready been called. For somewhat similar reasons, the new RCA recording of George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess might have drawn more notice (it still got an honorable mention) had not the London recording of the previous year already brought home to us, through its excellence, the real and lasting virtues of that masterpiece of the American musical theater.

The voting, as usual, was done by the critics and staff of the magazine. A so as usual, the records to be considered were those of our publishing year, January through December 1977, which is to say those records that were reviewed in one of those issues or that could have been reviewed in one of them but got temporarily overlooked. In the magazine business there is such a thing as "lead time," and records issued too late in the year therefore find themselves reviewed in the early issues of the following year.

THIS brings to the fore another built-in characteristic of our system: if we are not to create chaos we must stink by that publishing-year limitation. And so we honor, on occasion, a record that is as mulch as a year old, and we put off to next year what looks like another sure winner because it arrived too late for us to re view it. There were examples of both in our voting this year and though we claim no virtue for this aspect of our system (other than that of not forgetting quality just because time has passed). we look won it as a sort of trade-off for our ear y discoveries of good things to come. And we honestly feel that we have the better of the trade.

-James Goodfriend, Music Editor

SELECTED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF AND CRITICS FOR THE READERS OF STEREO REVEW

Certificate of Merit awarded to Richard Rodgers for his outstanding contributions to the quality of American musical life.

Honorable Mentions

ANNIE (Charles Strouse-Martin Charnin). Original Broadway Cast. COLUMBIA PS 34712.

ARRIAGA: Symphony in D Major; Overture to "Los Esclavos Felices" gesus Lopez Cobos cond.:. HNH 4001.

JACKSON BROWNE: The Pretender. ASYLUM 7E-1079.

JOSE CARRERAS: Aria Recital. PHILIPS-9500 203.

ELGAR: Cello Concerto; Enigma Variations (Jacqueline Du Pre, cello; Daniel Barenboim cond.). COLUMBIA M 34530.

FAURE: Complete Songs (Elly AmelinE, soprano; Gerard Souzay, baritone; Dalton Baldwin, piano). CONNOISSEUR SOCIETY CS 2127/8.

GERSHWIN: Porgy and Bess ( Houston Grand Opera, John DeMain cond.). RCA ARL3-2109.

DEXTER GORDON: Homecoming. COLUMBIA PG 34650.

HAYDN: Twenty-four Minuets (Philharmonia Hungarica, Antal Dorati cond.). LONDON STS-13359/60.

GEORGE JONES: I Wanta Sing. EPIC PE 34717.

TEDDI KING: Lovers and Losers. AUDIOPHILE AP 117.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 3 ( Marilyn Home, mezzo-soprano: Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, James Levine cond.). RCA ARL2-1757 MASSENET: Esclarmonde (Joan Sutherland, soprano; Giacomo Aragall, tenor; Richard Bonvnge cond.). LONDON OSA-13118.

MESSIAEN: Vingt Regards sur l'Enfant Jesus (Michel Berof, piano). CONNOISSEUR SOCIETY CS2-2133.

DAVID MUNROW: Music of the Gothic Era (Early Music Consort of London).DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON ARCHIV 2710 019.

CHRISTOPHER PARKENING: Guitar Music of Two Centuries. ANGEL S-36053.

GRAHAM PARKER AND THE RUMOUR: Heat Treatment. MERCURY SRM-1-1117.

BONNIE RAITT: Sweet Forgiveness. WARNER BROS. BS 2990.

SIDE BY SIDE BY SONDHEIM (Millicent Martin, Julia McKenzie, David Kernan, vocals; Ned Sherrin cond.). RCA CBL2-1851.

10cc: Deceptive Bends. MERCURY SRM-1-3702.

B. J. THOMAS. MCA-2286.

RICHARD THOMPSON: Live! (More or Less). ISLAND 9421.

WAGNER: Orchestral Excerpts (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Leopold Stokowski cond.). RCA ARL1-0498.

WEILL: Theater Pieces; Violin Concerto ( London Sinfonietta, David Atherton cond.). DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709 064.

PHIL WOODS SIX: Live from the Showboat. RCA BGL2-2202.

CRYSTAL GAYLE: We Must Believe in Magic. UNITE) ARTISTS UA-LA77 I-G.

DVORAK: Piano Quintet in A Major, Op. 81 (Emanuel Ax, piano; Cleveland Quartet). RCA ARL1-2240.

AL JARREAU: Look to the Rainbow. WARNER BROS. BZ 3052.

EGBERTO GISMONTI: Danca das Cabegas. ECM 1089.

COUSINS: Polkas, Waltzes, and Other Entertainments (Gerard Schwarz, cornet; Ronald Barron, trombone; Kenneth Cooper, piano). NONESUCH H-71341.

JAMES TAYLOR- JT. COLUMBIA IC 34811.

GRANADOS: Goyescas (Alicia de Larrocha, piano). LONDON CS-7009.

DUKAS: La Peri. ROUSSEL: Symphony No. 3 ( New York Philharmonic, Pierre Boulez cond.). COLUMBIA M 34201.

MILES DAVIS: Water Babies. COLUMBIA PC 34396.

THOMSON: Ali (Santa Fe Opera Company Raymond Leppard cond.). NEW WORLD NW 288/9.

VIVALDI: The Four Seasons. Op. 8, Nos. 1-4 (Simon Standage, violin; English Concert. Trevor Pinnock cond.). CRD 1025.

STEVIE WONDER: Songs to the Key of Life. TAMLA Ti 3-340CZ.

----------------

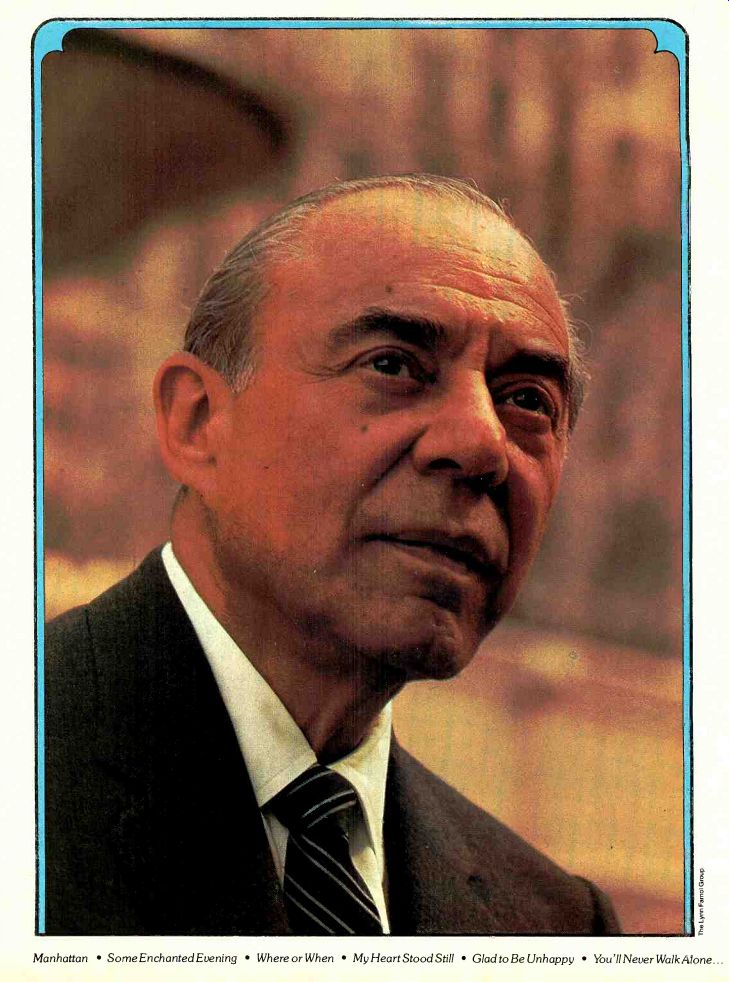

RICHARD RODGERS

Manhattan; Some Enchanted Evening; Where or When; My Heart Stood Still; Glad to Be Unhappy; You'll Never Walk Alone; My Romance; The Sweetest Sounds; Slaughteron Tenth Avenue; Soliloquy; If I Loued You ; Oklahoma; Thou Swell

If there is anyone who knows the musical theater, its art, its craft, its dreams, its realities, its expectations thoroughly and completely, it is ... RICHARD RODGERS.

RICHARD RODGERS is--or wants to appear to be--a far simpler man than you or I would ever suspect. At seventy-five he is the dean of the American musical theater, a prime determinant, for that matter, of the very nature of the American musical theater, the composer of dozens of shows we all remember and hundreds of songs we can never forget, a collector, for many years, of honors and of responsibilities, a man who has made a great deal of money and given a great deal of it away.

He takes it all as the most natural stream of occurrences, the career almost foreordained, the success a combination of background, labor, and the blind chance of public taste. Is he holding something back, or was the world really that much more simple, direct, and honest when he built his career than it is today?

IT depends on what we mean by "the I world." For Rodgers the world has always revolved around music American music, theater music. "My mother played the piano beautifully," Rodgers says. "She was the best sight reader I ever knew. My father loved to sing. They used to play and sing before and after dinner. They used to go to all the musical shows and then buy the score, and that was what they played and sang. I was around all the time.

That was my kind of music." Rodgers speaks today with difficulty, the result of a serious larynx operation, but clearly and with no lack of conviction. In the view of himself that he offers there was no other possible career but the one that was chosen. If there is in that just a hint of the directness and simplicity of plot of the musical stage, then perhaps that itself is a clue to the man.

Unlike that of many of America's songwriters, Rodgers' childhood back ground was not one of abysmal poverty and the Lower East Side of New York City, but the upper-middle-class life of a doctor's family considerably farther uptown. And the cultural background was not the European one of the immigrant, but that of the contemporary American scene. "My father was from Missouri; my mother was born in New York. I grew up on the corner of Morris Park; that's 120th Street, east of Lexington Avenue. We moved later to 86th Street, and when I graduated from public school there, I went to De Witt Clinton High School-which I didn't like very much." And then he went to prestigious Columbia University.

Why? "There was an important thing there: the varsity shows. That was my main reason for wanting to go to Columbia, because I wanted to write the varsity show. It seems silly now, but it was very important then." It was, and he did, the first Columbia freshman ever to do so. His lyric collaborator was a Columbia graduate (he was seven years older than Rodgers) named Lorenz M. Hart, and the show also contained two songs with lyrics by another Columbia graduate (also seven years older) named Oscar Hammerstein II.

Rodgers wrote his first songs at the age of fourteen, his first musical score at the age of fifteen, his first published songs at seventeen, and his first professional full score, Poor Little Ritz Girl, with lyrics by Hart, also at seventeen.

The show played in Boston and Atlantic City, had a New York run of 119 performances, and got a considerable number of favorable reviews in the New York newspapers. That's quite an accomplishment for a boy just about to enter his sophomore year in college, even though, for the New York presentation, a number of the Rodgers and Hart songs were scrapped and replaced by others by the more experienced By James Goodfriend team of Sigmund Romberg and Alex Gerber. Perhaps none of Rodgers' songs from that score can be said to be in the public consciousness today (none of the Romberg songs are either), but the year before, in 1919, a Rodgers and Hart song was interpolated into a musical comedy by Hale and Lynn called A Lonely Romeo. The song was Any Old Place with You. It was Rodgers and Hart's first published song together., and it can be said to be part of the public consciousness today-if not their first smash hit, then, across the years, their first "standard." THERE is a recognizable personality in that song, the personality of Rodgers-and-Hart as an entity rather than that of two separate people. The structure is old-fashioned: verse, chorus, verse (with new lyrics), chorus (with new lyrics but the same tag line). The chorus is short, only sixteen measures plus a two-measure tag at the end, and each of its four lines begins with the same melodic pattern, transposed, in the second and fourth, to different harmonic areas. The melodic figuration of the tag line appears no place else in the song.

In all, the song is simple but totally professional, the various structural characteristics match each other perfectly (the chorus had to be short because of the repeated verse; the tag had to be melodically distinctive and different because of the identical line openings; and so on), and the effect is, to coin a "Rodgers and Hart mastered what for centuries more 'serious' composers had not: the total integration of music, meaning, and the natural rhythm and flow of the English language." word, "catchy." (Could Sigmund Romberg ever be said to have written a "catchy" tune?) The song also contains, in its "catalog"-type lyrics, what may be the first of those typical, outrageous lines that we associate with Larry Hart: I'll go to hell for ya Or Philadelphia, Any old place with you.

And thus the collaboration that marked the first of what might be called Rodgers' three compositional periods--the second was with Hammer stein, the third with a variety of lyricists including himself-was set. Rodgers has been almost three different composers during his career, depending upon his collaborator. "I knew that I couldn't write the same sort of song for Oscar's lyrics as for Larry's," he says. And so, obviously, he didn't. But just what are the implications of that? In fact, did the words come first, or the music? The answer to that latter question is yes-or no. "In most cases I wrote a tune to fit the situation and the performer who would be singing the song in the show." Rodgers then gave Hart the tune and Hart wrote lyrics.

Was it the same with Hammerstein? "Just the opposite. Oscar wanted the freedom to write his lyrics first." The music came afterward. But in either event there was the commitment to write music that would fit the kind of lyric Rodgers knew he would get, that would, in essence, determine the musical style. Isn't that a terribly profound commitment? "Yes," says Rodgers, meaning "I suppose so." Rodgers, of course, has written lyrics himself (No Strings in 1962, which included the song The Sweetest Sounds). "I enjoyed writing lyrics," he says, "but it's very hard work. I don't know anyone who writes lyrics quickly. It's a mosaic kind of work: you get an idea and then move the pieces around. It's not like composing. You don't write one note at a time, you write whole phrases." Well, what about composing, then? How much actual "composing" does a songwriter, even a writer for the musical stage, actually do? For example, we know that in the Broadway theater the orchestrations are invariably done by someone else, a specialist in orchestrations (even Leonard Bernstein's West Side Story was orchestrated by other hands), but what about the harmonies, say, as they finally appear in the printed score? "The essential harmonies are mine," says Rodgers. "The simplification of them in the sheet music is the work of the editor at the publishing house. I wouldn't know how to get the chord I want into the simplified form that could be played by a fourteen-year-old girl. It's a very special talent. I write originally on three staves melody, harmony, and bass. And usually my originals for piano can't be played by two hands. They're too difficult. There's too much going on." Rodgers' work, as mentioned, can be divided into three separate periods, and it is no disrespect to the man to suggest that most of his best work came out of the first two. Some stage composers are meant to work alone, some need collaboration. Some struggle for years before finding the right collaborator.

Rodgers was fortunate in finding both his natural collaborators right at the be ginning, so that after the unfortunate death of the first, he did not have to search very long for a second. With Hammerstein's passing, though, in 1960, Rodgers was left very much on his own. True, there were fine lyricists around, but musical collaborations, like marriages, don't necessarily work just because both parties possess fine qualities. There has to be a spark.

There were certainly a lot of sparks with Hart. Among the shows they wrote, or partially wrote, together were Dearest Enemy, two different Garrick Gaieties, The Girl Friend, Peggy-Ann, A Connecticut Yankee, Present Arms, Spring Is Here, Heads Up!, Simple Simon, Evergreen, Jumbo, On Your Toes, Babes in Arms, I'd Rather Be Right, I Married an Angel, The Boys from Syracuse, Too Many Girls, By Jupiter, and, of course, Pal Joey, the last of which drew the (today) tremendous ly comic criticism, "Mr. Hart's lyrics are urbane to the point of smuttiness." The titles are perhaps more familiar the closer they are to the present (the last, By Jupiter, was 1942; Hart died in 1943). But it was, with only few exceptions, the individual songs rather than the scores that stuck in the mind. With the shows listed above (and in the same order), one can match up Here in My Arms, Manhattan and Mountain Greenery, The Blue Room, A Tree in the Park and Where's That Rainbow, My Heart Stood Still and Thou Swell, You Took Advantage of Me, With a Song in My Heart, A Ship With out a Sail, Ten Cents a Dance, Dancing on the Ceiling, Little Girl Blue and The Most Beautiful Girl in the World, There's a Small Hotel and Glad to Be Unhappy, Where or When and My Funny Valentine, I'll Tell the Man in the Street, Falling in Love with Love and This Can't Be Love, I Didn't Know What Time It Was, Everything I've Got and Wait Till You See Her, and Be witched, Bothered and Bewildered. These are only instances; there were more, from those and other shows, and from films. Short or long version, it is an astonishing list not just of hits but of real musical-lyrical achievements.

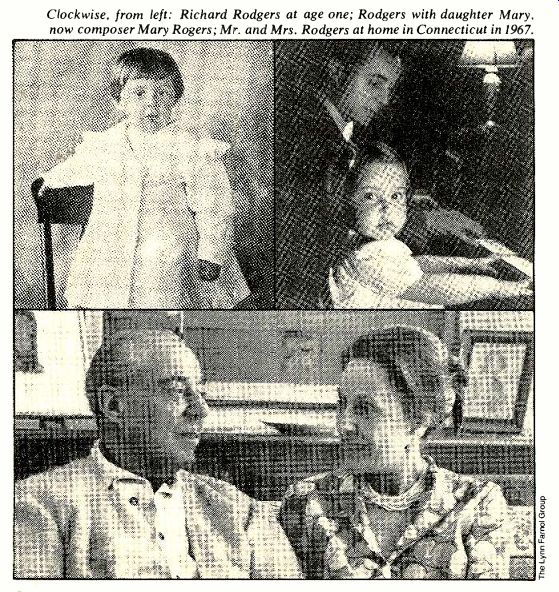

Clockwise, from left: Richard Rodgers at age one; Rodgers with daughter

Mary, now composer Mary Rogers; Mr. and Mrs. Rodgers at home in Connecticut

in 1967.

IT has been the fashion for some years now to say that Rodgers and Hart were better than Rodgers and Hammer stein. It isn't true. But Hart called forth from Rodgers (remember that commitment) a certain kind of song-clever, catchy, immediate, direct, and easily removable from its original dramatic context--a kind that Hammerstein never could. It was a less sophisticated musical stage then. Certain songs could be, and were, interchanged from one show to another (try switching around anything from South Pacific and The Sound of Music) without ill effect, be cause the real integration of book, song, and dance didn't come fully until later, the first attempt being Pal Joey.

So the songs, to a large extent, had to fend for themselves. A lot of good stuff went down the drain when the shows closed, but a lot of mediocre stuff, needed to fill out the score, was also mercifully laid to rest. The best songs, though, had an immediate and lasting life of their own apart from their shows.

And the best songs were really good. One still does not know which to ad mire more, the exuberance and inner rhymes of Hart's

All of it lovely, all of it thrilling, I'll never be willing to free her, When you see her, You won't believe your eyes

or the ecstatic, almost airborne music that Rodgers wrote for the situation and the singer without knowing what the lyrics were going to be. Can one express an admiration for

My funny valentine, Sweet comic valentine, You make me smile with my heart.

without also admiring the strange (for an American show song), haunting, mi nor-key melody that Rodgers provided for it? Which is more impressive, the cleverness of the very conception of a love song called I'll Tell the Man in the Street or the joyful, optimistically rising melodic line that begins it and dominates it throughout? The point is that, at their best, you can't take the songs apart. Rodgers and Hart mastered what for centuries more "serious" composers had not: the total integration of mu sic, meaning, and the natural rhythm and flow of the English language.

Rodgers, by the way, was by no means unaware of that "more serious" music.

He had left Columbia after his sophomore year and enrolled in the Institute of Musical Art (now Juilliard) where he spent his final collegiate years. It didn't seem to spoil him.

WITH the hindsight of years we recognize how radical a change marked the first of the Rodgers and Hammerstein collaborations, a change not only fn Rodgers' style and intent but in the very nature of the American musical theater as it had existed to that time.

Oklahoma was the first of the truly integrated musicals, integrated in the sense that book, lyrics, music, and dance were woven together to form an artistic whole. Earlier attempts to do anything of the sort were usually put down as "book shows," pretentious intellectual exercises by impractical non-professionals. But Oklahoma was different; it worked. It also wasn't hurt at all by a string of "hits" in the first scene--Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin', The Surrey with the Fringe on Top, Kansas City, I Cain 't Say No, Many a New Day, and People Will Say We're in Love, one after the other-for which one might well have to go back to the opening scene of Mozart's Marriage of Figaro to find a comparison.

It is fascinating, though, to read the contemporary reviews of Oklahoma.

They were complimentary, of course, even ecstatic at times, but one keeps on finding comments like "After a mild, somewhat monotonous beginning, it suddenly comes to life around the middle of the first act" (New York Post); "It is inclined to undue slowness at times and monotony creeps in ... " (New York World Telegram); "nothing much in the way of a book ..." (Time); and "reminds us at times of a good college show" (the New Republic). Some of the more perspicacious critics noticed that the show was "different," but none made what would to day be the logically expected statement: "Mr. Rodgers' songs, while of the highest possible quality, are categorically different from those he wrote before with Lorenz Hart." It just wasn't so obvious then.

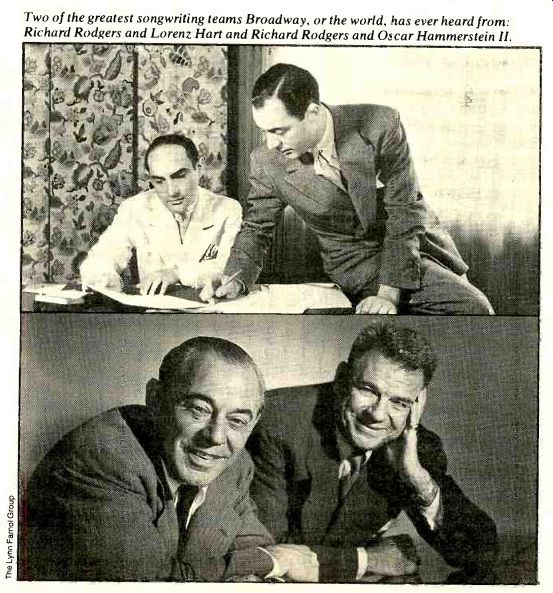

---- Two of the greatest songwriting teams Broadway, or the world,

has ever heard from:

Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II. The public, he feels, is still waiting and anxious for new musical comedies."

But it often takes years before works of art are properly understood (Beethoven could swear to that), and one picks on the critics only because their views-as opposed to the reactions of mere members of the audience-got put down in black and white for posterity to gloat over. Still, it is unsettling to compare bits of Brooks Atkinson's New York Times review of Pal Joey in 1940-"If it is possible to make an entertaining musical comedy out of an odious story, Pal Joey is it . . . some scabrous lyrics to one of Rodgers' most haunting tunes, Bewitched. . . . Al though it is expertly done, can you draw sweet water from a foul well?" with the same man's comments about the revival twelve years later:

" . . . no one is likely to be impervious to the tight organization of the production, the terseness of the writing, the liveliness and versatility of the score, and the easy perfection of the lyrics. . . . Brimming over with good music and fast on its toes, it renews confidence in the professionalism of the theatre. . . ." And two more, on the down side, from the first London production in 1954: ". . . something of a dramatic curio . . . a transition piece, its experimental quality is some excuse for its extreme ugliness. . . .

The sordid story is chiefly redeemed by Miss Carol Bruce, an actress of character. . . . She has the best song, Be witched, and she puts it across for a great deal more than its tasteless words are worth . . ." (London Times); and . carefully calculated to have no charm whatever. . . . Far from being a love philtre, Pal Joey is an emet ic. . . . Good tunes would have helped, so would a good comedian, so would some singing voices . . ." (Punch). It was perhaps such reviews that scared Rodgers away from further "tastelessness." But it is possible to be mature and musically sophisticated without being "tasteless," and that is the path Rodgers and Hammerstein pursued, even if few people really noticed it in all its aspects.

THE point about Oklahoma and, to a large extent, the shows that followed it, is a dual one. First, the songs are really a part of the story and, perhaps to a far greater degree than in any of his preceding works (Rodgers, perhaps, to the contrary), expressive of the personalities of the characters that sing them.

Most of them are only with difficulty removable from context. Yes, People Will Say We're in Love can be abstracted as an anytime, anywhere love song.

But the public that made a hit out of The Surrey with the Fringe on Top was singing, humming, and whistling about a conveyance that had long since passed from the general American scene, and in singing about it they were, in essence, re-creating the time, the place, and hence the show itself over again in their minds. The second part of the point is that while the lyrics were more homespun, more folksy, more sentimental, more extra-New York-regional than anything Hart could or would have turned out, the music was more sophisticated, more varied, "bigger" than what Rodgers had done before. The "catchiness" was gone, replaced by something else. The opening melodic phrase of Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin' is a musical statement of considerable, almost monumental sweep (try it as the opening theme of a lyrical symphony). "Well," says Rodgers, "with the situation of a cowboy admiring the view it was hard to avoid that." Oh. Of course. But you have to be able to create it too. Only geniuses do great things because they can't avoid them.

RODGERS had many hit songs with Hammerstein, perhaps-and perhaps partly because of the quite incredible growth of the record industry and musical broadcasting-even more than he had with Hart. But what sticks in the mind, because of their continuing integration of story and song, are whole scores rather than individual songs.

Not that Younger Than Springtime or If I Loved You are not great ballads on their own, but thinking of them some how brings back to mind virtually the entire scores, settings, and actions of South Pacific and Carousel. The inevitable catalog is de rigueur: Oklahoma! (2,212 performances on its first run), Carousel, the film State Fair, Allegro, South Pacific, The King and I, Me and Juliet, Pipe Dream, Flower Drum Song, The Sound of Music. The individual hit songs are almost too numerous to mention, and besides, those that were not hits the first time around are there to be rediscovered in revival. The King and I, as Rodgers says, is a bigger hit today in its revival (and, expectedly, getting better notices) than it was in its original production.

The sugar content of Hammerstein's lyrics could get a bit high at times, but that is the risk in the style in which he chose to write. No one, however, could have set those lyrics more sympathetically or tastefully than Rodgers. If there was a real flaw in the Rodgers and Hammerstein collaboration it lay in their concept of regionalism and in the predictability that came out of it. The exploring eye moved about and, finding a usable milieu, produced not some thing real drawn from that milieu, but the Rodgers-and-Hammerstein-musical of the Pacific War theater, the traveling circus, the Orient, the low life of Cannery Row, or the inhabitants of China town, San Francisco. It was superimposed on the subject to such an extent that it ultimately became a frozen technique to be analyzed and used by others. And others did. Still, it takes nothing away from the concrete accomplishments of the shows themselves.

Who else but Rodgers and Hammer stein could have touched the public heart so strongly with a quasi-operatic scena like Soliloquy that it became a pop hit? Who else could have so moved the American public that people would themselves sing of a mythical island, a million miles away, the like of which none could see and few really imagine? That is magic of a sort-of quitea sort.

AFTER Hammerstein's death in 1960, Rodgers went it alone, testing himself with both lyrics and music for addition al songs for a new version of the film State Fair, and then going all the way with the musical No Strings. The latter was, at least, a succ'es d'estime (it got both a Tony and a Grammy), and maybe a little more than that. It was also, probably, a more adventurous effort than Hammerstein would have agreed to. It was (Rodgers' contribution, anyway) masterly, but it didn't fly. Stephen Sondheim became Rodgers' partner for Do I Hear a Waltz, Martin Charnin for Two by Two, and Sheldon Harnick for the short-lived Rex. Of all the reasons suggested for the failure of the last, no one ever put forth the idea that it was the songs that were at fault. But there was none of that old spark. Sondheim, Charnin, and Harnick, excellent craftsmen all, were of a different generation from Rodgers'. Their world was a very different place from the one that Rodgers staked out for himself at so early an age and, to a great extent, continues to inhabit.

The public, he feels, is still waiting and anxious for new musical comedies.

Success is a matter only of finding the right people to write, the right actors to play. But is it so? Is the public, apart from the nostalgia crowd, really waiting for anything of the sort? No mention of Rodgers would be complete without itemizing some of those many honors and responsibilities

mentioned above. He is a director, a trustee, or a member of the American Theatre Wing, Barnard College, the National Institute of Arts and Letters, the Philharmonic Symphony of New York, the Juilliard School of Music, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. He has received medals from very nearly everybody who awards them, including Columbia University, the National Conference of Christians and Jews, the City of Boston, and the Advertising Federation of America, and honorary degrees from at least seven institutions. He himself has endowed scholarships and awards at Juilliard, the American Theatre Wing, and elsewhere. And the Rodgers and Hammerstein Archives of Recorded Sound in the New York Public Library at Lincoln Center were not named that for nothing.

BUT for all his public service, for all his honors, it is as a creator of musical theater that we look upon Rodgers and admire him. If there is anyone who knows the musical theater, its art, its craft, its dreams, its realities, its expectations thoroughly and completely, it is Richard Rodgers. And yet the view he offers of it and of his own role in it is al most naïve. Mr. Rodgers, whom do you write for? "I write for the situation and the character, and it has to be right for the way I feel about the situation and the character. Not for Joe Blow on Seventh Avenue. I don't know how to write for him. I don't know who he is." Mr. Rodgers, even if you don't consciously try to produce hits, do you know which songs are likely to become hits? "How can I know which song will become a hit eight months after the show opens? Some kid in a recording session makes an attractive record.

Somebody else picks it up and it be comes a hit. I couldn't have foreseen that. I can only say 'thanks.'" Mr. Rodgers, about those harmonic subtleties you wrote into Suzy . . . ? "Maybe I was just being a little smart alecky." Mr. Rodgers, did you consciously try to produce an art that was specifically American? "No. I just wrote in the style of what I was listening to." Mr. Rodgers, did the idea of an art form occur to you? "No. That would have been too self-conscious.

Never crossed my mind. I just wrote. . . . " Yes, didn't he! With genius.

And that is why Richard Rodgers is a great and original composer. And that is why Richard Rodgers is-or wants to appear to be-a far simpler man than you or I would ever suspect.

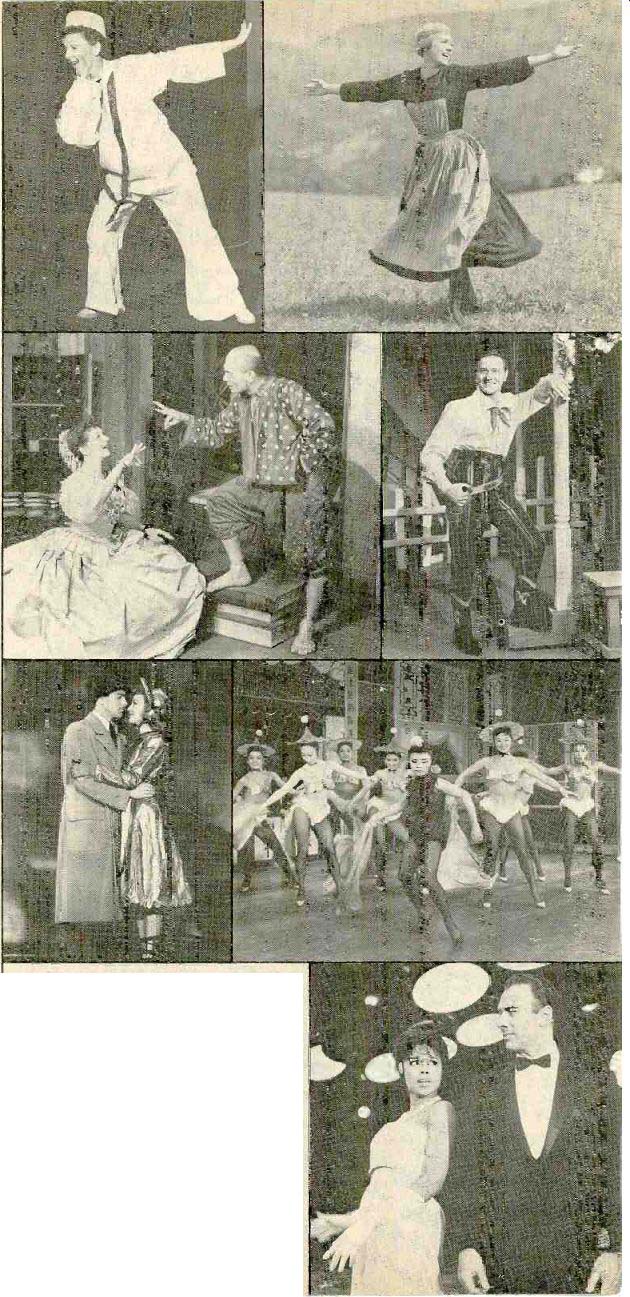

------------- From top, left to-right: Mary Martin as Nellie Forbush in

South Pacific (courtesy Museum of the City of New York); Julie Andrews,

as Maria in the film version of The Sound of Music (Movie Star News); Gertrude

Lawrence as Anna Leonowens and Yu! Brynner as the King in The King and I

(M.C.N.Y.); Alfred Drake as Curly in Oklahoma (M.C.N.Y.I; Gene Kelly as

Joey Evans and Ledo Ernst as Linda English in Pal Joey (M.C. N. Y.4; Pat

Suzuki as Linda Low with the dancing ensemble in Flower Drum Song (Lynn Farnol

Group); Diahann Carrot as Barbara Woodruff and Richard Klley as David Jordan

in No Strings (Lynn Farnol Group).

-----------------

Rodgers & Hart REVISITED

BEN BAGLEY, the intrepid and indefatigable retriever of lost songs by the masters of musical comedy, has been assembling the lesser-known works of Rodgers and Hart ever since 1961, when his first "Rodgers and Hart Revisited" album came out on Spruce Records. It is now available on Bagley's own Painted Smiles label (PS 1341), so one can still delight in such otherwise forgotten or half-forgotten songs as At the Roxy Music Hall, This Funny World, the opening number of the Garrick Gaieties, and a dozen others. A second volume (PS 1343) restored another fourteen items, and with the recent release of Volumes III and IV the Painted Smiles catalog holds a total of fifty-three uncelebrated Rodgers and Hart songs.

One might suppose that by this time Bagley and his crew would be scraping the absolute bottom of the barrel, but not so. Though he had to go to a great deal of trouble to track down some of the songs in these collections, the impression one gets after hearing them is that most of what Rodgers and Hart cut out of their shows is a good deal better than what many other songwriters leave in. Of course, not everything on these discs sticks to the ears as well as the hits that made these collaborators famous, but very little really falls flat either. And be sides the songs themselves we have the producer's witty, gossipy, and informative (though sometimes mischievously misleading) notes. It all adds up to a healthy double dose of entertainment.

FOR these latest "Rodgers and Hart Revisited" albums, Bagley lives up to his reputation for being able to persuade the unlikeliest performers to join his team. As the interpreter of I'm a Fool, Little One, He Was Too Good to Me, and Mornings at Seven, Estelle Parsons is every bit as compelling as she is currently on Broadway bulldozing a theater-full of "pupils" in Miss Margarida's Way.

Lynn Redgrave is no slouch as a singer either, whether solo or in duets. She's paired with Anthony Perkins in Someone Should Tell Them (inexplicably excised from A Connecticut Yankee in 1927) and with Arthur Siegel in The Letter Song (originally written for Jeannette Mac Donald and Maurice Chevalier in Love Me Tonight but scissored out of the final version of that film).

Anthony Perkins is an old standby in the "Revisited" series, and he sings attractively no matter what the assignment-a comic ballad from By Jupiter originally written for Ray Bolger, a romantic one written for the film of The Boys from Syracuse, or the touching I'm Talking to My Pal, clipped out of Pal Joey by director George Abbott because he considered it too downbeat.

-------------

BASIC RODGERS

The Boys from Syracuse. Nelson, Cassidy, Osterwald. COLUMBIA SPECIAL PRODUCTS COS 2580.

Carousel. Original Broadway Cast. MCA 2033E.

The King and I. Original Broadway Cast. MCA 2028E.

Oklahoma! Original Broadway Cast. MCA 2030E.

Pal Joey. Segal, Lang. COLUMBIA SPECIAL PRODUCTS COL 4364.

The Sound of Music. Original Broad way Cast. COLUMBIA S 32601.

South Pacific. Original Broadway Cast. COLUMBIA S 32604.

Victory at Sea, Volume 1. Orchestra, Bennett cond. RCA ANLI-0970.

Many of the shows with Hart are not now, or were not ever, available as complete scores. Good selections of many of the songs, though, may be found on the following records.

Ronny Whyte and Travis Hudson: It's Smooth, It's Smart, It's Rodgers and Hart. MONMOUTH-EVER GREEN 7069.

Ben Bagley's Rodgers and Hart Re visited, Volumes I, II, III, and IV. PAINTED SMILES 1341, 1343, 1366, and 1367 (see review herewith).

--------------------

Add in the pleasant, unaffected voice of Nancy Andrews, the still unstrained, true baritone of Johnny Desmond, and the extraordinary Blossom Dearie--the only woman I know who can sing in baby talk without making me physically ill and you'll have some idea of the variety of talent lavished on this retrieved material. Desmond is particularly winning in Now That I Know You from Two Weeks with Pay, a Broadway-bound revue (to which Cole Porter, George Gershwin, Harold Arlen, and Johnny Mercer also contributed) that never made it to opening night. And let's not forget Elaine Stritch, who makes the most of a win some sentimental trifle of the Twenties called A Little Souvenir.

There are some weak entries, to be sure, but they are rare enough considering the generous length of the two pro grams. Most of the lyrics radiate that special Hart brand of blithe charm, and the melodies sparkle. The deft Norman Paris, whom Bagley frequently used as an arranger, died before these albums were put together, but his replacement, Dennis Deal, turns out to be a real find.

Another fine arranger, Bub McCreery, is responsible for the Grand Finale at the end of Volume IV, which is a nonstop medley of Rodgers and Hart standards from The Lady Is a Tramp to Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered-sung by Nancy Andrews and Bagley's choral troupe, The Men and The Women.

Still another Painted Smiles Rodgers and Hart special is in preparation even now-a recording of the complete score of their Forties hit Too Many Girls-and Bagley says there are enough worthy rarities left to make at least two more "Revisited" volumes. Judging from the ones he's given us so far, they'll be well worth their price. -Paul Kresh

BEN BAGLEY'S RODGERS AND HART REVISITED, VOLUME III.

Nancy Andrews, Blossom Deafie, Johnny Desmond, Estelle Parsons, Anthony Perkins, Lynn Redgrave, and Arthur accompaniment, Dennis Deal arr. and cond. Medley--It's a Lovely Day for a Murder/Mornings at Seven/How's Your Health?; Someone Should Tell Them; Damsel Who Done All the Dirt; Life Was Monotonous; Why Do It?; I'm a Fool, Little One; The Letter Song; We'll Be the Same; Medley-Where the Hudson River Flows/I'd Like to Hide It/The Hermits;

Are You My Love?; Nothing to Do but Relax; He Was Too Good to Me; Women; Who Are You?; Medley-It's Just That Kind of a Play/Sky City/I've Got to Get Back to New York. PAINTED SMILES PS 1366 $7.98.

BEN BAGLEY'S RODGERS AND HART REVISITED, VOLUME IV.

Elaine Stritch, Nancy Andrews, Blossom Deafie, Johnny Desmond, Anthony Perkins, and Lynn Redgrave (vocals); Arthur Siegel (piano); vocal and instrumental accompaniment, Dennis Deal arr. and cond. Medley-Knees/It Must Be Heaven/Me for You; I Love You More Than Yesterday; I Can Do Wonders with You; Queen Elizabeth; Now That I Know You; Medley-Did You Ever Get Stung?/A Twinkle in Your Eye/How to Win Friends and Influence People; Medley-Take and Take and Take/I'd Rather Be Right/Sweet Sixty-five; I'm Talking to My Pal; Fool Meets Fool; A Little Souvenir; You're the Mother Type; Moon of My Delight; Grand Finale. PAINTED SMILES PS 1367 $7.98.

---------------

---------------

----------------

Also see:

BEST RECORDINGS OF THE PAST TWENTY YEARS: Our reviewing panel selects the best recordings of the past twenty years

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)