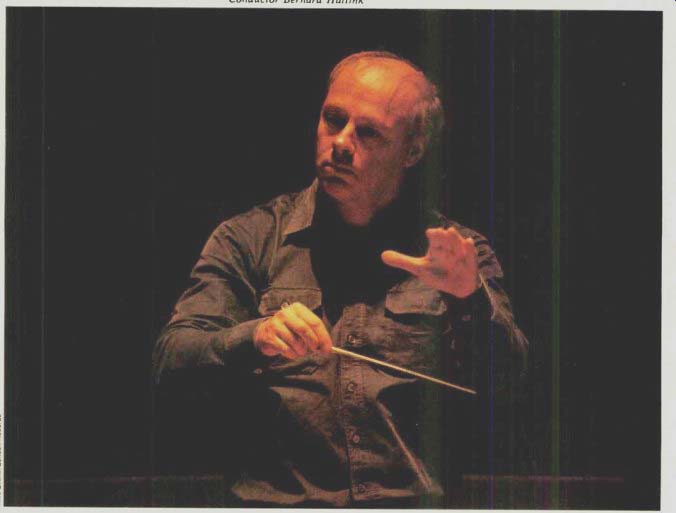

State-of-the-Art Sound For Bernard Haitink's Illuminating Reading of Shostakovich's Fifth

--------- Conductor Bernard Haitink

BERNARD HAITINK'S new London digital recording of Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony is the first in his cycle of that composer's symphonies to be made with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra. The acoustical qualities of the venerable Concertgebouw hall add something special in the way of tonal warmth for the strings and brilliance for the brass, as well as the kind of spatial ambience this music needs.

More important than the quality of the recording, however, is that Haitink, unlike most non-Soviet interpreters, has chosen to treat the Fifth Symphony as something other than a display vehicle for a virtuoso orchestra. Impending tragic conflict is very much evident in his reading of the opening passages, and at the end of the first movement the icy tones of the glockenspiel verge on the spooky. The second movement assumes a mood of menacing sarcasm in stead of being treated as the usual Mahleresque jeu d'esprit. As in almost all performances of the Fifth, the slow movement is the high point. The build up toward the first climax is long, slow, and rock steady, and the coda after the final climax has a chilling, almost disembodied character similar to pages of the Sibelius Fourth Symphony.

The finale remains the hardest part of this work to bring off, chiefly be cause the seemingly monumental coda, with its solemn fanfare built on a major-mode variant of the first four notes of the opening, simply does not grow organically out of what came before. The ferociously militant opening pages of the movement virtually play them selves, but when the lyrical interlude arrives, the problem is to keep it from sounding banal or cloying. Haitink gets top honors for his reading, which is remarkably convincing.

In the music that works up to the final fanfare of the coda, the dotted woodwind figuration is similar to that used in Boris Godunov prior to the "spontaneous demonstration" of the people in the opera's opening scene.

This brings up Shostakovich's own comment about the Fifth, which is quoted by London's annotator, Timothy Day, and, more fully, by Solomon Volkov in the controversial and emotionally harrowing book Testimony The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich (Harper and Row, 1979): "I think it is clear to everyone what happens in the Fifth. The rejoicing is forced, created under threat, as in Boris Godunov. It's as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, 'Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing,' and you rise shaky, and go marching off, muttering, 'Our business is rejoicing, our business is rejoicing.' " Soviet tradition calls for an ultra-solemn treatment of the finale of the Fifth, and in his recording of it with the Leningrad Philharmonic Yevgeny Mravinsky takes almost four minutes to traverse the coda. At the other extreme, Leonard Bernstein, apparently taking his cue from Koussevitzky's Boston Symphony performances in the 1940's, plays it in a brisk two and a quarter minutes. I find neither of these versions as satisfying as Haitink's, which, at three minutes, ten seconds, is just five seconds faster than the early 1970's Melodiya/Angel recording by the composer's son, Maxim.

Overall, Haitink's performance here strikes me as one of the most illuminating versions of the Fifth on records. The only other recording of this symphony that I find comparable with Haitink's is the one by Maxim Shostakovich (now available on Quintessence), but the new one enjoys two distinct advantages over its predecessor: the Concertgebouw Orchestra is far superior to the USSR Symphony, and the state-of-the-art digital sonics are truly splendid.

-David Hall SHOSTAKOVICH: Symphony No. 5, Op. 47. Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra, Bernard Haitink cond. LONDON 3 LDR 71051 $12.98, 0 LDR5 71051 $12.98.

++++++++++++++++

Juilliard Quartet: Robert Mann. Earl Carlyss, Joel Krosnick. and Samuel Rhodes

The Juilliard Quartet's Third Bartok Set Ranks Among the Very Finest

THERE have been a dozen integral recordings of the six Bartok quartets released in this country alone since Columbia issued the first in 1950. That one was by the original Juilliard String Quartet--consisting of Robert Mann, Robert Koff, Raphael Hillyer, and Arthur Winograd-and among its successors was a 1963 stereo version by the Juilliard with Isidore Cohen and Claus Adam replacing Koff and Winograd, respectively. The recent Bartok centennial and the ascendancy of digital recording technology have combined to stimulate today's Juilliard Quartet Earl Carlyss, Samuel Rhodes, and Joel Krosnick are now the colleagues of first violinist Robert Mann-to tackle these six masterpieces again. Sonically the results are very fine, and musically the set compares well with the finest of those by such current competitors as the Tokyo, Hungarian, and Lindsay Quartets.

The 1963 Juilliard recording, which is still available, showed a somewhat more flexible approach to the music than did the group's generally fierce and youthful 1950 readings while retaining a sinewy texture and the slashing rhythmic attacks. Further interpretive changes in this newest series of performances seem essentially minor. The two early quartets are played with great tonal richness but also with great attention to their linear elements. As might be expected, the real excitement comes with the mature works, beginning with the taut, compressed Quartet No. 3 and working up to the full amalgamation of the ethnic and the universal in the Quartets Nos. 4, 5, and 6. Indeed, I feel about these last three works the way I do about the Brahms symphonies: m favorite is the last one I listened to.

It is in these latter works too, with their amazing variety of color, that the advantages of digital mastering become most evident. The tremendous reduction in background noise level, together with the virtually noiseless CBS pressings, has resulted in a dynamic range that makes possible a true pianissimo as well as effective capture of subtle timbral effects, most strikingly in the three middle movements of Quartet No. 4 (which for the present happens to be my favorite). The sonic ambience is richer and airier in the new Juilliard recording than in either of the two earlier versions. In only a few small respects do I find that the 1963 performances have an edge--a more emphatically conclusive ending to Quartet No. 5 and a more generally effective communication of the elegiac tone of Quartet No. 6.

I note that the new CBS package has retained James Goodfriend's excellent commentary and analysis from the earlier stereo issue (including the typo that has Bartok making posthumous [1956] revisions to the First Quartet). Newly added is a rather opaquely worded essay by Milton Babbitt on the structural aspects of the six quartets; it's fine for specialists, but it will be hard going for the ordinary listener.

-David Hall

BARTOK: String Quartets Nos. 1-6. Juilliard Quartet. CBS 0 I3M 37857, 13T 37857. no list price.

----------------

Also see: