Enthusiastic public response to digital compact disc has rejuvenated the audio industry.

BY DANIEL SWEENEY

The recorded-music industry, throughout most of its early one hundred years of existence, has shown itself to be profoundly conservative. It consistently supported the basic storage medium of the analog, stylus-groove phonograph record from the 1890's until the beginning of this decade. While the industry has per mitted itself certain evolutionary improvements--electrically cut records in 1923, microgroove LP's and 45's in 1948, stereophonic records in 1958, and quadraphonic records a dozen years ago-the rule for all such innovations was that compatibility with pre-existing disc formats he maintained.

But in 1983 the industry introduced the digital, laser-scanned Compact Disc and broke that rule.

The Compact Disc is not a refinement of the phonograph record, but a rival, incompatible format aimed at the same market niche. The audio consumer is being asked to change over and to make a decisive break with the past. Will he do it? Evidently he will. By industry estimates, so far in the United States almost 400,000 CD players have been sold, and the manner in which the market for players and discs is growing suggests that Compact Discs will eventually supersede phonograph records, if not entirely, at least very largely. The weight of industry opinion sees CD dominance over the phonograph by 1990 if not before. Although industry spokespersons do have a strong vested interest in promoting the new format, and the figure of 400,000 itself is not very impressive when compared with the sixty to eighty million turntables in the U.S., strong evidence exists to sup port the notion of a very rapid changeover. At this point the CD is very, very unlikely to fail, and its progress far surpasses initial predictions.

Why is the success of the new format so certain? For a great number of reasons. The most significant of these arc:

(1) the unanimity of manufacturers in adopting uniform HERE standards for digital mastering and for the Compact Disc itself, (2) the successful prior marketing of digitally mastered phonograph records, (3) the extensive promotional efforts by hardware and software manufacturers, (4) the rapid licensing of hardware and software manufacturers, (5) the high profitability of Compact Discs for manufacturers and retailers, (6) the cautious introduction of hardware and the successful wooing of the crucial enthusiast market, and (7) ultimately the attitude of the buying public toward the new format.

But beyond all of these individual reasons lies the collective determination of the audio industry to introduce a product that would stimulate explosive growth analogous to that which it experienced in the Sixties and early Seventies. By 1975 growth in home audio was flattening out, and by the time the Compact Disc was introduced in 1983 growth had virtually ceased. In 1984, for the first time in three years, the industry enjoyed double digit growth, and much of that growth was due to the success of the CD. The Compact Disc was an enormous gamble to revive a slack industry. It seems to have paid off.

A New Technology

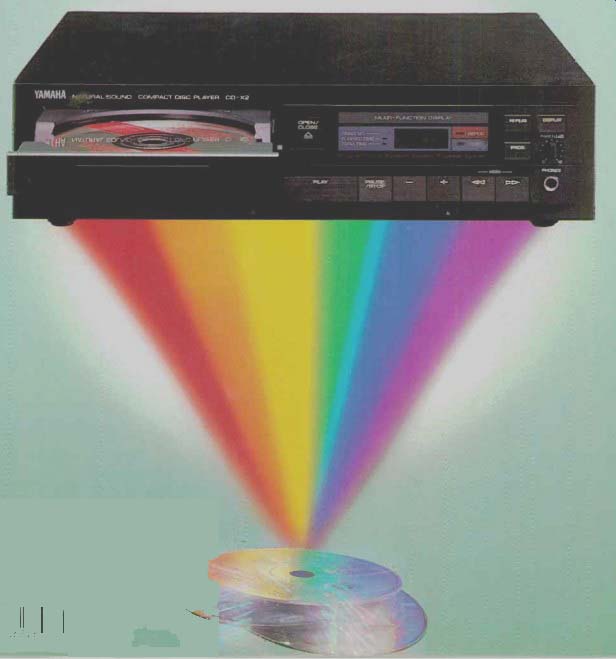

In a technical sense the Compact Disc represents the convergence of two technologies, digital encoding of audio frequencies and laser-scanned optical-disc data storage.

This convergence represents a deliberate choice on .he part of the industry. The industry could have opted for an analog laser-scanned optical audio disc (similar to the audio tracks on a video disc), but it did not, primarily because of prior developments in the recording industry favoring a digital medium.

Digital recording was done experimentally at MIT in the 1950's and was subject to serious development in the late Sixties and early Seventies by the British Broadcasting Company and by Nippon Columbia (Denon). The promise of digital re cording was an ability to preserve high-quality audio information in definitely and to provide for exact copies of master recordings, considerations that were becoming increasingly important in the 1970's with the advent of multi-million-selling albums. The analog master tapes of certain smash hits, such as Fleetwood Mac's Rumours, were literally played to death to make copies or "running masters" for the pressing plants. In an age of enormous production runs analog recording was showing its limitations.

But it was in classical rather than popular music that digital mastering really made its initial impact. In the early Seventies the first digitally mastered classical LP's were issued by Denon, and by 1977 a number of small audiophile labels such as Telarc and Delos had adopted digital mastering and were winning adherents in the small but influential audiophile community. By 1979 most of the major classical la bels had be gun releasing digitally mastered phonograph records and selling them at premium prices. Digitally mastered recordings quickly caught on among classical buyers (a small group, but disproportionately heavy spenders on both hardware and software), and by the close of 1982, the majority of new classical releases were digitally mastered. Now, in 1985, no major classical label still masters only in analog and just a handful of smaller classical labels continue to do so.

In popular music the progress of digital mastering has not been so swift. Most popular recordings are made on twenty-four- or thirty-two-track machines, and digital versions of the same are still rare and extremely expensive. But digital mastering is steadily increasing in the pop field, and, in any case, a Compact Disc can easily be produced from an analog master. The continued use of analog tape recorders in pop music is not likely to retard the progress of the Compact Disc. It hasn't held it back so far.

Digital mastering itself was only a prelude--a testing of the waters, so to speak-and the digitally mastered LP has provided merely a transition period during which the record-buying public could be educated as to the advantages of digital recording. Even before digital mastering had assumed dominance within the small classical enclave, the Japanese consumer electronics industry had already made its collective decision to launch a new consumer format.

A Single Format

According to Marc Finer, a spokesman for Sony's audio division, both Sony Corporation and Philips of the Netherlands worked independently during the early Seventies to develop a laser-scanned, optical-recording, digital disc for mat. Both companies succeeded in developing a practical product, and during 1977 and 1978 they compared their work and agreed to develop a single standard, a 4.72-inch (12-centimeter) disc encoded with a sixteen-bit digital signal. In 1978 Sony and Philips jointly pro posed the new medium as a standard consumer format to the powerful Electronic Industries Association of Japan. In 1980 the Sony-Philips standard was accepted, and licenses were issued to manufacturers throughout the world.

In the meantime, Philips, in con junction with Pioneer, had introduced a laser-scanned audio/video format called LaserVision. LaserVision demonstrated the effectiveness of the new optical storage system (albeit within an analog format), al though it failed to make a major impact on the video scene, coming as it did at time when VCR formats were proliferating in that chaotic new market. The Compact Disc, arriving a full five years after LaserVision, does not suffer from the format rivalry still troubling the video field, and that factor in very large measure accounts for the CD's success thus far and will assure its future success as well.

The matter of the standardization of the CD format cannot be stressed too strongly, for in the past format wars have had a stifling effect on innovation in the consumer electronics industry in general and on audio in particular. Look back on the audio industry over the past quarter of a century. Stereo phonograph records arrived in a single format, and they almost completely replaced mono LP's in seven years.

In analog tape, on the other hand, five rival formats battled it out through the Sixties and Seventies open-reel, four-track, eight-track, cassette, and Elcassette. The cassette took a good fifteen years to assume dominance, more than twenty to assume its present total dominance.

Most chastening to the industry was the quadraphonic (four-channel) surround-sound phonograph record. The quad format rivalry proved not just troublesome but fatal. No fewer than six formats strove for public acceptance-Electro-Voice Matrix, QS, SQ, CD-4, UD-4, and Ambisonics. Today they're all dead or virtually dead.

The major audio manufacturers had no wish to repeat the disasters of the quad era or the near disaster of analog tape, and the Compact Disc was brought out in one format and one format only. There were other digital-disc formats proposed, but they lost out fairly early to the CD. Today Compact Discs are manufactured in standard form for scores of record labels around the world, and the basic CD standards will almost certainly remain unaltered at least until the year 2000.

By 1981 the industry was ready to introduce the CD and began demonstrating it at engineering conferences, but a worldwide recession delayed mass production. An economic upturn in 1983 signaled that the time had come, and players and discs appeared in the U.S. during the fall of that year (they had appeared in Japan a year before). In a matter of three months, 30,000 to 40,000 players were sold in spite of poor availability of discs and retail prices for players in the $1,000 range. Last year 225,000 to 230,000 CD players were sold (figures provided by Electronic Industries Association and by Audio Times). Audio Times estimates that 500,000 more will be sold in 1985. Contrast this with LaserVision video, available here since 1978. Less than 250,000 LaserVision machines have been sold in the U.S. in over six years.

In under two years the Compact Disc player has proved a phenomenally successful medium. Even if sales flattened out, the industry would still have a strong stake in the format. But in fact sales have been increasing every month. Moreover, with player prices, at least on close outs, as low as $200, and with players appearing in $600 rack systems, CD is now available at every level of the market. Even the casual buyer of midline stereo equipment is being confronted with the CD player as a component choice.

According to Sony's Finer, "By the end of the decade, there will be no reason to buy a turntable on cost considerations. Low-end CD players will be competitively priced with low-end turntables. The phono graph will become obsolete." Software sales have been more dramatic still. The players, though remarkably hot sellers for a new medium, accounted for only a little over 3 percent of total consumer audio sales in the U.S. last year. But in record stores CD's account for at least 10 percent of retail dollars nationwide, and many retailers claim they could sell twice the number of the discs they do now if the pressing plants could supply them.

In major cities Compact Discs can account for a significant fraction of dollar volume for the software retailer. The Laury's chain in Chicago does about 50 percent of its dollar volume in CD's, while Tower Records in Washington, D.C., does roughly 33 percent. Tower Records in New York and Los Angeles both report 15 to 20 percent.

According to Robin Ahrold, a spokesman for RCA, these high sales figures reflect the fact that people who buy CD players are frequent purchasers of software. Many appear to be in the process of rebuilding their record collections.

Ahrold adds that they are frequently the same individuals who purchased phonograph records heavily in the past, and in many cases they continue to buy LP's heavily too, supporting both formats as it were.

It should be noted here that the American recording industry is basically supported by a relatively small number of individuals who buy at least ten records a year.

These same heavy buyers, who comprise only about 5 percent of the owners of component stereo systems, are evidently flocking to the CD medium, thus accounting for the fact that at least forty times as many CD's as CD players were sold last year in the U.S. market. This augurs well for the future of the medium, because it shows that a significant percentage of the influential enthusiast buyers have already been won over.

Is the LP Doomed?

Perhaps not coincidentally, last year was generally a slow period for the audiophile LP. Sales of the latter, particularly of audiophile Japanese pressings of popular releases, have fallen off markedly, and many of the audiophile labels are now doing the bulk of their business in Compact Discs. Sheffield Lab and Reference Recordings, two of the best and most prominent such la bels, are both deriving approximately 70 percent of their revenues from the sale of CD's, even though spokespersons for both companies have avowed the sonic superiority of state-of-the-art analog records over the Compact Disc. By contrast, Delos and Telarc, two audiophile labels that embraced digital recording from the onset, do 80 and 90 percent of their respective dollar volumes in CD's.

Of course, black vinyl still rules the recording industry as a whole, but record-company executives are not lamenting its imminent decline.

"Vinyl is an almost impossible medium to work in," says Emilia Heygood, founder of Delos Records, reflecting a common complaint in the industry. "It's so hard to get a [master disc] recording right, and the [pressing] rejection rate is so high.

With CD's, as long as you're dealing with an established plant, the quality control and consistency are very good." Elliott Mazer, a noted independent record producer, concurs.

"The rejection rate for CD's is much lower than for phonograph records. Records are a headache, but right now they cost less than half as much to produce. The cost differential will change in the future, though." Another commercial advantage of the Compact Disc is that, unlike records and tapes, it cannot be easily bootlegged.

CD production re quires very elaborate industrial facilities. Organized crime will not soon be able to operate anything so conspicuous as a CD pressing plant, and the record industry knows this. With losses from bootlegging running into the tens of millions, the industry has strong grounds to support the CD format for reasons of profitability alone.

And the recording industry has supported the CD unconditionally.

An indication of the seriousness of industry commitment is the current number of titles available in the format. Over 2,500 CD titles have been released so far, and more than 5,000 should be available by the end of the year. At first, program material was heavily weighted toward classical music, but currently almost all styles of music are represented, and the simultaneous release of popular and classical albums on phonograph record, cassette, and CD has be come commonplace. Contrast this with the quadraphonic debacle: quad releases numbered only in the hundreds at the format's height.

Still another factor suggesting a rapid transition is the situation of triple inventory (LP's, CD's, cassettes) currently facing record retailers. They'd prefer a single medium.

Retailer objections to multiple inventories helped to kill quad and retarded the growth of the cassette market for years. The same objections at first worked against the Compact Disc, but now that retailers realize that the medium has won acceptance and is in the ascendant, they look forward to the disappearance of the bulky, troublesome vinyl disc.

Does all of this suggest the rapid replacement of the phonograph record and the turntable by the Compact Disc and its player? And what of the cassette-currently well ahead of vinyl records and CD's on the world market and still growing rapidly? Where will the CD fit into the total software picture when it at last becomes a "mature" category? The feeling in the industry is that CD sales will achieve "dollar parity" with record sales within five years and perhaps as early as three.

Robert Heiblim, vice president of sales and marketing for Denon, states, "CD's will overtake phonograph records sometime within the decade. [Sales of] turntables will de cline by 15 to 20 percent every year thereafter, and within six years [the turntable] will be a minor [component] category. By 1990 record companies will be making a choice should we continue pressing records?" Yet Heiblim does not predict the total extinction of the phono graph: "There will be a market for very high-quality analog records in the Nineties." Marc Finer of Sony takes a more extreme position. "The CD will be come the single music medium. It's suitable for portable and automotive applications as well as use in the home. It will largely displace cassettes because there's no longer any need to dub music off of records." And Emiel Petrone, senior vice president of PolyGram Records and chairman of the industry wide Compact Disc Group, predicts dollar parity between CD's and records in the United States as early as 1987. "Once parity is achieved," he says, "the decline of the phono graph record will be very rapid." At the same time, Petrone hesitates to predict the total disappearance of the phonograph. "I think it will survive on the low end," he asserts.

Despite these predictions, none of the major record labels have indicated plans for phasing out record production, and the rapid obsolescence of the cassette format seems even less likely by most accounts.

Prerecorded cassettes and cassette decks are inexpensive to make and extremely profitable. CD hardware and software may never appear at equally attractive price points.

But no one argues that the phono graph record is not in serious trouble, not even Doug Sax, president of Sheffield Lab, or Marcia Martin, marketing director of Reference Recordings. I asked both of them the same question: "What is the future of the analog record?" "We think that there will continue to be a small market for quality analog records," said Martin.

"Many people still object to the sound quality of existing digital formats, and many of the same people have invested in very expensive turntables. We think the American market in the nineties will ultimately be about twenty thousand people." (That figure, incidentally, is based in part on subscription totals for leading "underground" audio journals, at least two of which have taken strong editorial positions against Compact Discs.) Doug Sax's answer to my question was more cautious. "I don't know how big the market is. I know that the phonograph record is still the best playback medium for the home, and I believe that we can continue to sell records. I am going to Europe to record major symphony orchestras in analog--possibly the last time that this will be done. I think it's important that at least some of the significant musical performances of the present be preserved in this way. I hope our records find an audience," Sax adds. "If they don't, we stand to lose a lot of money." The long-term survival of a shrunken analog industry is certainly possible. After all, a market for vacuum-tube electronics continues to exist twenty years after most manufacturers went solid-state. In deed, tube devotees voice many of the same objections to the "transistor sound" that analog diehards do to digital recording. But without the support of the larger consumer electronics industry, analog disc recording and playback will remain essentially static, and makers of analog records will be forced to toil on with aging disc-cutting lathes and cutting amps that will eventually be un-repairable. It's hard to predict a secure future for an orphan industry.

Of course, the Compact Disc itself may be superseded. Other digital storage media have been developed, and more will follow, some with greater information--storage capabilities, record-erase provisions, and various other advantages. But the music industry is certain to stand behind the CD at least into the next century, and in its time the Compact Disc will be the dominant medium.

====================

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)