by Roy Hemming

A young American conductor escapes category and redefines tradition.

My father, my grandfather, and my uncles knew the whole Gershwin family when they all lived in Brooklyn. My father, in particular, played George's music continually on the piano when I was growing up, and he played it the way he had known George to play it back in the early days. So I got used to hearing it played in a stylistically correct manner that very few people hear any more."

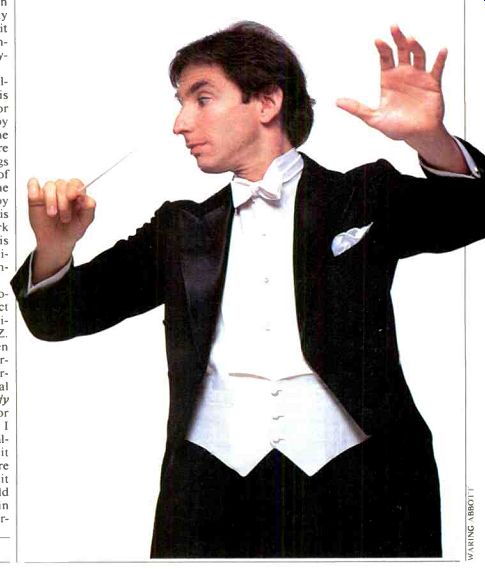

Conductor-pianist Michael Tilson Thomas was talking about his newest Gershwin record release for CBS Masterworks. Performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the music includes several obscure Gershwin pieces in first recordings as well as the original versions of both the Rhapsody in Blue and the Second Rhapsody, restored by Thomas himself. As we talked in his book- and score-filled New York apartment, his enthusiasm for his current recording projects was evident in his virtually nonstop comments about them.

Thomas's current-and ongoing-Gershwin recording project began almost accidentally. The initial impetus came from Thomas Z. Shepard and Andrew Kazdin, then both producers for CBS Master works. "Andy asked if I'd be interested in conducting the original jazz-band version of the Rhapsody in Blue as an accompaniment for George's own 1925 piano roll. I knew the Gershwin piano roll, al though to my ears at that point it sounded fast and I was afraid there might be problems in matching it correctly. But I also knew the old acoustic recording that Gershwin made with Paul Whiteman's Orchestra in 1924, so I was aware that Gershwin's conception was faster, and different, from the ones we've become accustomed to hearing in the concert hall and on discs.

"So we made that recording of the Rhapsody in Blue, and it won a lot of interesting comments," Thomas said with evident pride. Then with another CBS producer, Steven Epstein, he recorded an album of Gershwin overtures with the Buffalo Philharmonic during the third of his eight seasons as the orchestra's music director (1971-1979), and the record later became a best-seller.

"Little by little, I felt this was leading me in the direction of wanting to do something about the way Gershwin's pieces were really meant to sound things that were in my bloodstream but that I'd previously hesitated to do.

I began to approach Gershwin's pieces the way some musicians approach and seek out the original versions of works by various other composers.

"I had long taken enormous delight in the fact that whenever I played some of Gershwin's piano pieces at informal gatherings, and played them in the original style, people were fascinated," Thomas continued. "At the same time, for a young classical musician arriving on the scene as I did in the early Seventies, everyone was full of advice about what I should do and shouldn't do. I was told I should do plenty of Mozart and Brahms and this and that-but not Gershwin. Gershwin was considered 'pops.' Yet I felt it was a really important mission for me to undertake anyway because I was so deeply involved emotionally in the material."

About this time, Thomas played part of Gershwin's Second Rhapsody in a telecast of a Young People's Concert of the New York Philharmonic. "It just didn't sound the way I remembered it from my child hood," he recalled. "I remembered certain alternations of patterns be tween plucked strings and wood winds and piano, and they weren't in the score we had. Then I discovered the piece had been edited and revised by somebody after Gershwin's death. I began a quest to find the original. Thanks to the lyricist

Ira Gershwin, George's brother, I learned that the manuscript was in the Library of Congress. My memory about the differences proved correct. I was able to make new parts and restore the piece to the way George had first written it-and that's what we've recorded.

"I think the time has come to appreciate that Gershwin's genius and vision were very, very special that the chords had exactly a certain shape and a certain spacing because he wanted them that way. And the Los Angeles Philharmonic has been a joy to work with on the Gershwin recordings because they have such a great sense of style and rhythm." Could some of that come, I asked, from their also working in the near by movie studios and having more contact with popular-music styles, old and new, than symphony musicians in some other areas? "I think many of them have worked in the studios over the years," Thomas answered, "but we've also worked together very carefully on these pieces over a long period." Gershwin isn't the only composer Thomas has been seeking new approaches to, on and off records. Several seasons ago he began recording chamber-ensemble versions of the Beethoven symphonies-recordings that, to the surprise of many, have won more favorable reviews in supposedly more traditionalist Britain and Europe than in the United States.

"I've always been someone who's had to find my own path," said Thomas, who at age forty has finally begun to outgrow the Wunderkind label that has stuck to him since he first shot into the national spotlight in his early twenties. "My initial approach to composers such as Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, and Brahms," he admitted, "was to per form only their lesser-known pieces.

I was trying to develop a hands-on sense of musical style without falling into the inevitable traps and clichés of following famous past performances, especially the ones we know from recordings.

"But as I began to approach the Beethoven sym phonies, I kept coming up with the fact that the wonderfully massive sonority of the large modern orchestra, although it can be pleasing in certain pieces, got in the way of many interesting textures present in this music. For example, the way Beethoven subtly uses winds to underscore one line at a time in a growing orchestral tutu, or the way in which too much string sound can obscure intricate figurations in the lower piccolo or bassoon parts. With a large orchestra, there are passages that listeners perceive only as a kind of blare of sound, without hearing all the intricate figurations that are taking place.

"I started thinking about the size of the orchestra in Beethoven's time and, above all, the size of the rooms where most concerts took place," Thomas continued. "I realized that Beethoven's symphonies were originally a kind of expanded chamber-music experience. I decided to try performing Beethoven's Sixth Symphony, the Pastoral, with the English Chamber Orchestra, as a kind of experiment.

The results were so gratifying in terms of clarification of texture, in being able to shape and breathe life into certain phrases, that I went on to some of the other Beethoven symphonies with the same approach." In addition to the Sixth, Thomas has now recorded the Fourth, Fifth, and Seventh Symphonies of Beethoven with the English Chamber Orchestra. The rest, he said, are "in the works." Including the Ninth, I asked? Thomas smiled. "I think that one will be slightly expanded in relation to the others." Are the chamber versions of the Beethoven symphonies something that work better for recordings than for live concerts in our major halls? "That depends on the hall," Thomas replied, "and the rest of the program. I've done the Sixth with a reduced orchestra in the wide expanses of Tanglewood, and it was a very successful, beautiful performance. In general, I believe that the ideal Beethoven is about twelve violins, as compared with a standard today of sixteen or eighteen. With twelve you have a mass of sound but also more possibility of delicacy and flexibility." Since he left the Buffalo Philharmonic in 1979, Thomas has not had an orchestral home base. In stead, he has freelanced as a conductor, though be tween 1981 and this past spring he served as principal guest conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic for part of each season.

Freelancing has enabled him to record different repertoire with different orchestras, which means he's been able to capitalize on what Steven Epstein, still his CBS record producer, calls the "special qualities" of different orchestras for the different cycles--the Los Angeles Philharmonic for Gershwin, the English Chamber Orchestra for Beethoven, and the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra for Charles Ives.

Why a Dutch orchestra for America's own Ives? "Because," Thomas replied without hesitation, "the Amsterdam Concertgebouw is a bona fide, internationally recognized 'Romantic' orchestra that can bring to these performances a warmth and a breadth of conception that I think is very important.

Ives, after all, is the most adventurous of all the Romantic composers.

But his reputation, and most people's understanding of his music, has been complicated by the perception of Ives as an avant-garde experimental composer.

"Certain aspects of Ives's activities were avant-garde or experimental," Thomas noted, "but the direction of his music was completely Romantic. He was concerned with an expansion of expression, while retaining some of the great values of what he felt was most noble or most beautiful in America's past." Thomas said he is particularly baffled by how little young musicians today know about Ives and the American musical traditions that Ives quotes. "It's quite unbelievable that so few of the students I have in the summer at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Institute know any of the historic tunes of William Billings or Justin Morgan, or the work songs and minstrel songs of the nineteenth century, the folk songs and popular music –hall songs, the most famous hymn tunes, the political rallying songs, or even the songs of the American musical theater of the first half of this century. It's shocking-and such a pity. It cuts people off from their own country and its history. I some times think there are no people on earth as culturally disenfranchised as Americans." Despite his ultra-busy schedule as a freelancer, does Thomas miss not having an orchestra of his own? He bristled a bit at the question. "I like to think," he replied, "that for most of my professional life I've been a musical investigator. I've done performances of early music and cycles of unknown works by Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, and so on. I've done contemporary works by Steve Reich, David Del Tredici, Oliver Knussen, and others, as well as the Janatek operas and works by Stravinsky and Debussy, for which I have such enormous devotion, not to mention the Gershwin and Ives we talked about. I've tried to keep all these plates in the air at once, in what looks like a complex juggling act. I suppose." Thomas paused a second or two before continuing. "I remember Gregor Piatigorsky, the late, great cellist, warning me about this. He used to say, 'You are interested in so many things and can do so many things that it will always be confusing to people. They will never understand it. To you, it will seem completely logical why you're doing this or what's interesting about that. But others will be puzzled because they won't be able to categorize you.' "That's true. I've been called a Romantic musician, a Neo-Romantic, an avant-garde musician, a pop musician, and an acerbic intellectual. I think I'm an adventurous Romantic who hates dogma. I like to pursue all kinds of different music. And that's exactly what I've been able to do these past few years. Many of these different strands are now coming together, especially with regard to recordings.

"That doesn't mean, however, that the time may not come when my desires to be a musical leader and investigator will team up with the forces of a great orchestra with the vision and the courage to pursue various projects with me--and a public with sufficient curiosity to find them exciting too. That will be a very happy day." Thomas gave a performance last year, with a major orchestra, of Beethoven's Eroica that ended with a simultaneous burst of boos and bravos. "That was terrific!" he said.

"Someone told me that in the restaurants and bars around that particular concert complex, people stayed later than usual talking about the concert and debating it. That's what music should be." Roy Hemming is the producer of the New York Philharmonic's weekly national radio broadcasts. His latest book. The Melody Lingers On: The Great Songwriters & Their Movie Musicals. is due from New market

Also see: Classical (Jul. 1985)