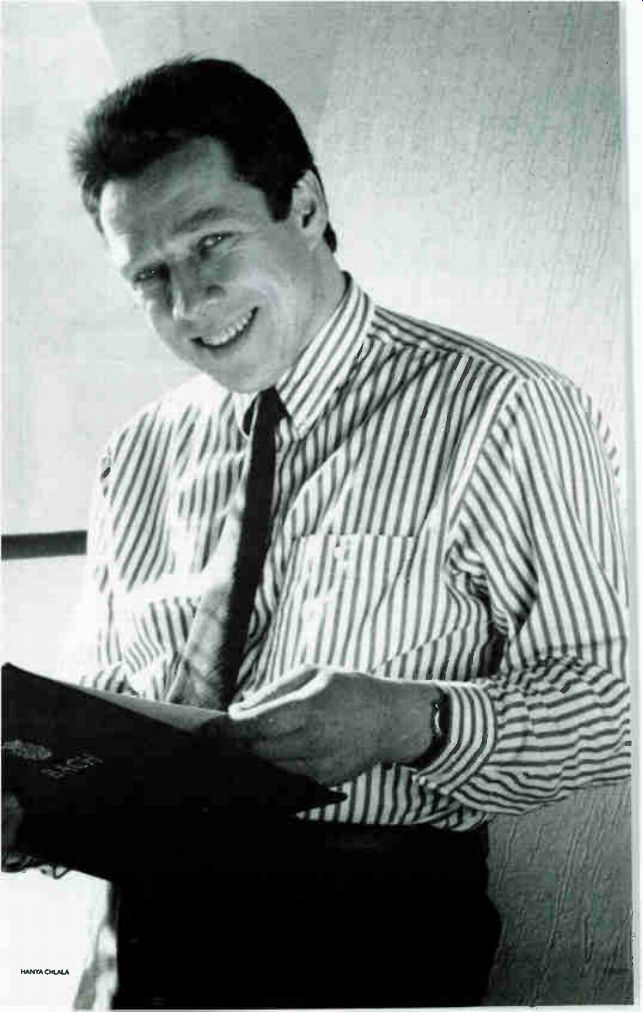

----------- Roy Goodman conducting The Hanover Band

| Home | Audio mag. | Stereo Review mag. | High Fidelity mag. | AE/AA mag.

|

D.R. MARTIN TALKS WITH ROY GOODMAN

Though not nearly as well known as Hogwood, Pinnock, and Norrington, Roy Goodman has been a part of London's vibrant period-instrument scene virtually since the beginning, in the late '70s. He played fiddle under those three, as well as under Gardiner, and started conducting in 1981. He was co-director of The Parley of Instruments. And for seven years he's been musical director of The Hanover Band, also not as well known as some of its peers.

On Nimbus, he and the Hanover Band have cut a prolific swath through the classical/early romantic repertoire, including the first complete period-instrument Beethoven symphonies set (on which he shared conducting credit with Monica Huggett) and various Haydn, Mozart, Weber, Schubert, and Mendelssohn works. More lately, he and The Band have undertaken a Haydn symphonies cycle for Hyperion, in direct competition with Hog wood. He's also started to record for Hyperion with his own period instrument group, The Brandenburg Consort.

While Goodman's music making may not evince the sheen of Hogwood or the probing intellect of Norrington, he can almost always be counted on to produce bright, entertaining readings; mostly on the surface, sometimes a little ragged, but comely and engaging.

The typical Goodman Nimbus recording seems very much like a live performance, perhaps because of Nimbus's commitment to long takes, where possible.

Goodman took time to chat while on an American tour with The Hanover Band.

According to his manager, several months after this conversation he severed his relationship with Nimbus; no surprise, given the frankness with which he questioned the way Nimbus handled his recordings.

I GOT A BAROQUE VIOLIN IN 1977, AND THERE WAS NO LOOKING BACK.

D.R. Martin: Tell me a little bit about how you became a period-instrument music-maker in the first place.

Roy Goodman: Well, I started life as a boy chorister [at King's College, Cambridge] and sang quite a lot of 16th-century music.' And 15 years ago, in '75, I formed a group that played baroque music on modem instruments. During the first couple of years of this group-in '75, '76-some of my friends went and studied in Vienna with Harnoncourt and came back and said, "Look at what he's doing. We've got to do this music on the right instruments." I've always thought that was the right thing to do. But my question to my friends was: "Who do we play with? There isn't anyone else to make music with. We can play trio sonatas, but there's no way of forming an orchestra!' It was really a fantastic stroke of luck that, at the same time, most of the period instrument groups in England started to be active. It was the early days of Hogwood's and Pinnock's orchestras. I got a baroque violin in 1977, and there was no looking back, really. I suddenly found that within about six months I had several years of work in the diary.

DRM: Why then? Why that particular time?

RG: There were several things. We were very lucky that commercially the thing took off in such a big way in England. For example, Christopher Hogwood tried to employ the maximum number of musicians as often as possible.

And whilst that turned the place into something of a factory for early music, it did actually give us all an enormous amount of experience. And the vast majority of people playing at that time had a very strong motivation which had nothing to do with commercial prospects. In fact, I think we all thought the commercial side of things, the bubble, would burst. I certainly gave it a maximum of five or ten years. The reason we felt that way was because we couldn't believe that something we felt about so passionately would conquer the world. Our motives were very purist at that time.

DRM: So you and your colleagues didn't think that you'd make lifelong careers out of this? RG: I think we all thought we could make a lifelong career out of it. But I think we thought we'd be hiding away in a little comer somewhere, doing it within a very small circle. The surprise to us all has been the success of the recordings.

There will always be a public both for and against; there's no point in pretending there aren't critics of what we do, sometimes fast and furious.

But there is an enormous public who do absolutely adore the sound of these instruments and the colors that they make. For me that's one of the most exciting things.

DRM: In general, how has the period-instrument movement in England been regarded by modern-instrument orchestras and players? Do they tend to have a curmudgeonly view of the whole business? RG: I think there's a great deal of ignorance or misinformation about period performance. I've read several articles that quoted conductors like Colin Davis and Neville Marriner, who really seem to be unaware of what period 1 Goodman was the solo treble on that fabulous 1964 London recording of the Allegri Misere, reissued in 1988 on London Jubilee 421 147-2.

-JA

orchestras are capable of doing these days. But look at someone like Charles Mackerras, who is a fantastically enlightened man. He is able to just stand in front of a period orchestra in London, flick his wrists, show all the marvelous technique, yet somehow bring something that feels very right to period performances. Which for me is very refreshing. If someone such as he can bring such professionalism to period-instrument performance, and excite all of us, there must be many more like him who can do that. For example, I've heard recordings of Colin Davis's Mozart and Haydn, and for me the results are fantastic. The Haydn he did for Philips with the Concertgebouw is absolutely superb. Many of the principles he uses to direct performances like those are directly applicable to our performances as well.

I would love to see someone like him involved in our kind of performances.

I think until they actually do that, until they get off the fence and just commit themselves, I see no point in them being downright rude about what they think period performances are. If they really started working with the people who are doing this, they'd realize we share the same values, we do share the same kinds of phrasing and everything else. We may be not as technically efficient as some of our modern counterparts, but we're actually after the same goal.

I WOULD LOVE IT IF EVERYBODY IN THE MUSIC COLLEGES HAD A COMPULSORY PERIOD OF ACTUALLY PLAYING ON PERIOD INSTRUMENTS.

DRM: So what we need is a serious interchange between the two disciplines.

RG: I think it works very much both ways. I'd like to see more period instrumentalists being able to work with modern symphonic players, to offer ways of widening their vocabulary of sonority and articulation, to show what's possible on the old instruments. I would love it if everybody in the music colleges had a compulsory period of three, six months, whatever, actually experiencing playing on period instruments. Every flutist should know what an 18th-century flute looked like, how it was played, what the cross fingerings could do, how you could do finger-vibrato and all these other things in these pieces that they will probably be playing on their modern instruments.

DRM: Has the period-instrument movement done anything to bring about changes in the Academy of St.-Martin-in-the-Fields, or the English Chamber Orchestra? RG: It has. For example, Neville Marriner has made very clear that he has to tread much more carefully on what repertoire the Academy performs. It's very rare now to hear Handel concerti grossi, Bach suites, and so on played on modern instruments. That's almost gone out the window. In the Haydn/ Mozart repertoire they are acutely aware of how it goes. Sir Charles Groves, at the age of 75 or so, even he has been listening to some Mozart on period instruments and reading a bit about period performance practice, and has changed his ideas. Another rather tangible thing is that the Philharmonia Orchestra, one of the big four in London, now play a lot of their turn-of the-century French repertoire on the kind of woodwind instruments that were used in France at that time; which is a completely different fingering system and produces a very different sound quality. If you heard the beginning of The Rite of Spring played on a 1910 French bassoon, I think it would sound quite different from a contemporary instrument.

DRM: So now we're talking about "authentic" Stravinsky? RG: We could joke about the word "authentic," but the answer to your question is definitely yes. You only have to listen to recordings of Elgar, for instance. His violinists all had gut E-strings. Heifetz played with a gut E string virtually all his life, I gather. That's really a phenomenal difference, because violinists with steel E-strings avoid playing an open E-string like the plague. If you have the possibility of using a gut string-which can be hazardous-it does totally affect your fingering system, how you climb up the strings. Because if you're able to use the open E-string, then it changes all your technique.

I WOULD JUST PUT B-L-A-N-D AGAINST MOST MODERN PERFORMANCES THAT I LISTEN TO OF THE REPERTOIRE THAT WE PLAY.

DRM: Many people still seem to think of period performance as dry, scholarly, and abstruse.

I was talking to Neville Marriner once, and he referred to the period-instrument movement as "the brown-bread bunch."

RG: It would be impossible to say it's dry and scholarly. I think I would just put B-L-A-N-D, in capital letters, against most modern performances that I listen to, of the repertoire that we play. That's why I homed in earlier on something like Colin Davis's Haydn recordings for Philips, because for me they represent what modern playing should be like: they are wonderful interpretations within a classical framework. That's really what I feel we're aiming at. To say that you're producing something that's a museum piece is absolutely outrageous, because that's the last thing we do.

DRM: Did you happen to read the long review Charles Rosen wrote in The New York Review of Books a while back, of Authenticity and Early Music, edited by Nicholas Kenyon?

RG: I'm afraid I didn't. I have read most of the book, though.

DRM: As you know, Charles Rosen is quite an erudite fellow. . .

RG: Oh, absolutely. The Classical Style and all that.

DRM: The upshot of his argument is that while authentic-music makers may well be on the dot in terms of scholarship and the specifics of original performance, he feels that authentic music-making has reduced the formerly pre-eminent issue of interpretation to second-class status. He says, "We no longer try to infer what Bach would have liked. Instead, we ascertain how he was played during his lifetime, in what style, with which instruments, and how many of them there were in his orchestra. This substitutes genuine research for sympathy, and it makes a study of the conditions of old performance more urgent than a study of the text."

RG: Sad to say, but that's a load of cobblers. This is terribly misinformed. Has Charles Rosen ever sat in on an orchestral rehearsal with Frans Brüggen, Roger Norrington, me? The answer's no, he's never been there. If he had, if he'd sat in on the rehearsal we had for our performance yesterday, he would have realized that we spent three solid hours interpreting. We did little else.

Most of the rehearsal was spent shaping phrases, considering what Mozart's slurs and articulations meant, differences between dots and dashes on the notes, and actually what they imply with regard to dynamic and shape and rhythm and all the rest. Putting all of that together and actually creating a very interpreted performance. But it's within the parameters of performance practice of that time. It's knowing what those parameters are, then trying to get the most out of it that you can. That's the exciting thing. I could put on a performance of Jeffrey Tate and the English Chamber Orchestra playing the same repertoire, and I could ask, "Who's been interpreting what?" I can't hear any interpretation on that at all. Every note has exactly the same shape, the same length, the same volume. I hear no interpretation whatsoever, yet people talk about the structural strength of it all. I'm taking Tate and the ECO as an example, but these kinds of records get rave reviews worldwide.

I THINK NIMBUS IS A LITTLE BIT NAÏVE TO THINK THAT YOU CAN RECORD BEETHOVEN'S NINTH-WHICH WE HAVE DONE-SIMPLY ON ONE MICROPHONE.

DRM: You and the Hanover Band are currently in the process of recording the Haydn symphonies for Hyperion. Tell me about that.

RG: I'm very excited about [the Haydn cycle], because artistically I've felt we've been occasionally at odds with the Nimbus sound. It hasn't always produced the sound of the orchestra in the way that I hear and perceive it. They like a very spacious acoustic, much more so than I would ever choose myself.

And they have a very idiosyncratic recording technique, one Ambisonic microphone, which is probably the most sophisticated microphone in the world. But it is for them a sort of black-and-white business. You have this one microphone in one position, and that is that and there's no arguing with it. Whilst I agree that the overriding principle is for the simplest technique possible that will do the job, I think that they're a little bit naïve to think that you can record Beethoven's Ninth-which we have done-simply on one microphone It creates terrible problems for us, getting the right balance The woodwinds, to me, regularly sound as if they're in the bathroom of the house next door. I've beat my head against the wall sometimes, thinking about how to improve this. The long and short of it is that if you're limiting yourself to this one kind of technique-and minimal editing, which is another

----------- Roy Goodman conducting The Hanover Band

principle of theirs, resulting in pretty well live performances-it does make life hard. Not least because, for my ears, the final product is nothing like as competitive as I'd like it to be. [In the Haydn cycle,] for the first time I've heard the Band approaching--well, I shouldn't say for the first time, but it is true--what I want it to sound like on disc.

There's no question at all that Nimbus have been the most amazing providers for the Hanover Band. Without Nimbus there would not be a Hanover Band, though the orchestra was formed several years before they started recording: Nimbus provided the finance that's enabled the orchestra to go on concert tours. So of course we try to work as hand-in-hand as we can. I've just felt that artistically for me it's become increasingly difficult to have control over the result I would like. When I got the Schubert Ninth CD-because I get no edited tapes at all from them--I put on the first few bars and I virtually cried. I couldn't believe that the one tape, which I'd gone into the control room and indicated that that was the one-and everyone agreed-was not the one that's on the record. And the one that's on the record was the one of which I said, "Not that one." Life should be much more simple.

DRM: Anyone who takes time to look through the player rosters on some of their earlier English period-instrument recordings, from the late '70s to the early '80s, is going to see your name in a lot off middle sections on recordings by Hogwood, Pinnock, and Gardiner.

How would you characterize the strengths and weaknesses of these conductors, maybe starting with Hogwood?

RG: That's a leading question, isn't it? [laughs] Well, I've worked for Hogwood for a long time. He began the musical education of a lot of us, myself included. Although he's been the one often put forward for his lack of interpretation, he is a very cultured and educated man. We learned a lot from him; not necessarily when he was standing in front of the orchestra, but from talking to him about his concepts and ideas of music.

DRM: How about Pinnock?

RG: Some of the first records we made [with Pinnock] we thought were absolutely fantastic at the time; I remember that quite clearly. But over the intervening decade or so they do sometimes sound very sour in intonation and . . .Well, the very first one now sounds like outtakes. I think when Trevor started recording for Deutsche Grammophon, one of his priorities was to clean up the string intonation and to get everything sounding much more professional, if you like. In other words, yes, we've got the enthusiasm from the players and they've all got the right attitude, but we've got to try to make it competitive. So the ensemble has to be better, the tuning has to be better, and we have to try to get away from the seasickness sort of phrasing that was going on at the time.

IN JOHN ELIOT GARDINER'S RECORDINGS, WHICH I DID NOT SO MUCH ENJOY AT THE TIME OF RECORDING, I REALIZE THEY DO HAVE A FANTASTIC QUALITY ABOUT THEM.

DRM: And Gardiner?

RG: John Eliot Gardiner has always been quite a hard man. I would say from the beginning he's been the most autocratic of the English [period instrument] directors. I think when you're like that you inevitably get a lot of people's backs up. I played with him in a period parallel to Pinnock.

When the English Baroque Soloists began, it was almost exactly the same orchestra as the English Concert. Despite that, the orchestras sounded completely and utterly different. It comes down to priorities, really. I think that John Eliot Gardiner wanted to impose his musical ideas on us a lot more than Trevor Pinnock did. For me the end result of all that has been one of surprise: Although Pinnock's results have always been very professional, at the last resort, with hindsight, some of the final product's a little more bland and dull than I had felt when I was performing them. But in John Eliot Gardiner's recordings, which I did not so much enjoy at the time of recording, I realize they do have a fantastic quality about them as far as professional standards of playing go. If you like a strong concept of the music making, particularly one of drama, you'll like Gardiner.

DRM: You've worked with Norrington, as well, and he seems to be the hot item these days. What was it like playing for him?

RG: It's amazing how things change. I remember when I played for a short while in the Kent Opera in the early '80s. The orchestra was virtually going to offer our services, so that Roger Norrington could make a record. He'd no discography at all in [orchestral] repertoire. So I think that gives you a hint as to what we felt about him. There was definitely a sort of propulsion to his music-making that was very exciting. He was actually one of the last on the scene, and he may have capitalized on that. We, the Hanover Band, were playing classical repertoire and recording it before he had thought of it. In 1981 we did a Beethoven concert in London with the Hanover Band, which was the first concert I directed. And lo and behold, who was in the front row of the audience but Roger Norrington? To my knowledge, that was the very first time he had ever heard Beethoven played on period instruments. The rest is history. There's no question at all that he's had a lot of color and flair in his personality, and he's had a very quick rise to stardom.

Which I think in many ways he fully deserves.

I'D FORGO THAT INDEFINABLE WARMTH THAT'S LACKING IN CD’s, WITHOUT QUESTION, FOR ALL OF THE CONVENIENCE AND EXTRA QUALITY.

DRM: Are you a record collector?

RG: Yes, passionately. I've had a collection of four or five thousand LPs for quite a few years. And I've become a CD collector now, totally, 100 percent. I'm very curious about modern technology for its own sake, including word processing and all the rest of it. But I find it very strange when people say they miss this indefinable warmth that's lacking in CDs. I must say, I've got pretty good ears. And I'd forgo that warmth, without question, for all of the convenience and extra quality that's available in CDs.

DRM: Even granting the wonderful qualities of vinyl, it was and is a big pain cleaning records, replacing styli, setting tracking weight and alignments, all that rigmarole.

RG: To get a really good result [from LPs], you have to be patient and do those things all the time. So no, I wouldn't look back on LPs with nostalgia. CDs are a wonderful medium. Of course, CDs also enabled a lot of musicians to rerecord a lot of things they'd put to bed as LPs.

DRM: In addition to bringing out a lot of back catalog stuff that nobody would have thought of reissuing on LP. Just look how the big labels are delving into their vaults, pulling up stuff that hasn't been seen in 15, 20, 30 years.

RG: Yes, that's right. The sad thing is that some major labels still emphasize a certain stock repertoire. They haven't all been as imaginative and enterprising as they might have been.

DRM: That's how all these labels that were tiny little operations a decade ago have found a way to blossom.

RG: Hyperion was such a label. And Ted Perry, who runs it, was one of the managing directors of Saga. He's one of the great entrepreneurs in records in England. He gave Janet Baker and John Shirley-Quirk their very first albums, for Saga. He then joined in with John Shuttleworth and they began Meridian Records. They had financial difficulties and Ted Perry was driving a cab around London to make ends meet. He'd spend the night driving a cab and the day sorting out his recording company. I had a lot of sympathy for him, because he's a man with a lot of heart and soul, a man who's very black-and-white in his ideas. If there's something that interests him, he'll do it, and he'll come out very clear about it. Or you can suggest something mainstream and he'll say no, that's dull. He's built Hyperion into a fantastic catalog.

DRM: Plus, you have Nimbus and Chandos there in Great Britain, these classy mid-sized labels doing interesting things. Unfortunately, we don't have anything really analogous in the US. There are some good little labels, but they hardly have much presence in the market. Labels like Telarc and Pro Arte might have gone that way, but they veered off into a lot of Pops stuff and got pretty stodgy in terms of classical repertoire. . .What kind of music do you enjoy listening to when you're off duty?

RG: I've got incredibly wide tastes. I've got three kids and the oldest is 18. I've lived through a lot of years of pop music with them. I really like almost any thing. Some of the latest funky house music I can't take at all; it just goes on and on and on. Almost everything else. I listen to a lot of jazz. I can switch into a different mode when I'm listening and when I'm going to concerts.

Where shall I start? Count Basie, Elgar, Shostakovich . . .

DRM: What a trio!

[adapted from Nov-1992 issue]

Also see:

BUILDING A MUSIC LIBRARY -- Munch and BSO

Prev. | Next |