From Stereophile, Jan. 1999.

Lucky me. To live out every rock fan’s fantasy— being given a personal tour

of the legendary Abbey Road Studios by none other than Alan Parsons. Entering

the hallowed ground of Studio 2 (largely unchanged from when the Beatles recorded

there), I clapped my hands to test the acoustic, then couldn’t resist the urge

to shout “I’ve got blisters on me fingers!” It sounded really good in there.

Alan Parsons has been involved with Abbey Road from the time he was assistant engineer on the Beatles’ Abbey Road and Let It Be. He went on to lend his engineering genius to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, and to produce such classic albums as Al Stewart’s Year of the Cat He’s also well known for his own Alan Parsons Project records— they’ve earned him 11 Grammy nominations — and for creating the finest-sounding rock records. Is there a single high-end audio dealer on the planet who doesn’t continue to use Parsons’ work as demo material?

“Nowadays, Alan, you’re considered to be one of the foremost experts on surround sound, as well as a big proponent of surround for music.”

“I think it will see me through the rest of my days. The last record I did, On Air, was actually sort of partially conceived for the medium, in fact — in the same way that Dark Side of the Moon was partially conceived for Quadraphonic. I could play you a couple of things which I think represent the medium rather well and offer different approaches to surround.”

We had settled in Abbey Road’s Penthouse Studio, a beautifully appointed space where we were surrounded by five (five!) of B&W’s flagship Nautilus 801 loudspeakers, each atop a custom pedestal holding a dedicated Chord amplifier.

“Okay, so where’s the sweet spot? I guess it would be tight in there, the chair in the middle.”

“What I actually like about surround is that everybody thinks that the sweet spot is completely mandatory. I like to wander around. I like to see what’s coming out of each speaker.”

The first of the DTS-encoded discs we listened to was Bonnie Raitt’s Road Tested — the live version of “Thing Called Love” This was easily the best surround setup I’d ever heard, with the stellar 801s effortlessly producing the highest to the lowest frequencies in a very natural presentation. The record did a creditable job of recreating the live concert experience, though the point of view was slightly skewed forward of the audience, due to some guitar sound in the rear speakers. Not that audiophiles are ones to pick nits, of course. It was quite enjoyable.

For a complete change of pace, Alan put on “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” from a DTS-encoded reissue of Marvin Gaye’s Greatest Hits.

“I feel they did a particularly nice job of reinterpreting for surround — a pretty good example of hitting the center channel with a very distinct sound. I said it was going to take me to the end of my career. If you can get results like that from something so old...”

“How do you feel about the fact that this changes the original artist’s finished work?”

“I think that was a very sensitive mix. I don’t think they’ve changed the music at all.”

Begrudgingly, I had to agree. There was nothing “tricky” about the mix, just a big, warm presence to MG’S vocals, with the occasional “chink” of the rhythm guitar on the beat, dead front and center.

“If you could have your choice, would you listen in surround all the time? Do you listen in surround at home?”

“The funny thing is, I almost never actually sit down at home to listen to music. It’s always background, while puttering around the kitchen or just milling about the house in general. If I didn’t do this job, would I sit down and listen to more music? The answer is probably yes. I remember in my teens, I certainly did do that—I used to actually strap the headphones on and disappear into my own little world. Then I got my first job in audio, at a tape-duplication plant. That’s the first time I really felt that I’d heard hi-fi , and it made a very significant and lasting impression. Music had a completely different effect, and from that day on, I suppose I spent just about every day listening to music on a really good system. That’s, in a way, why any thing that I could have at home would have always been a compromise.”

“What kind of listening setup did you have at home at the time?”

“It was always a little bit boffin-like, as I would call it. Basically it was strung together with wires trailing across the floor and lots of clicks and buzzes before anything would actually happen. I had no money at that time, so I tended to literally beg, borrow, and steal to get any kind of music happening at home. And it was very much mono. I was a fanatic for the likes of Cliff and the Shadows and the early Who stuff. I was the first in the shops to buy the second Beatles album. At the time, for the music that I wanted to hear, stereo was just not the same, really. Even Sergeant Pepper was not really conceived for stereo.”

“Right. I’ve been scouring London for mono Parlophone Beatles records and that kind of thing. The early monos sound far better.”

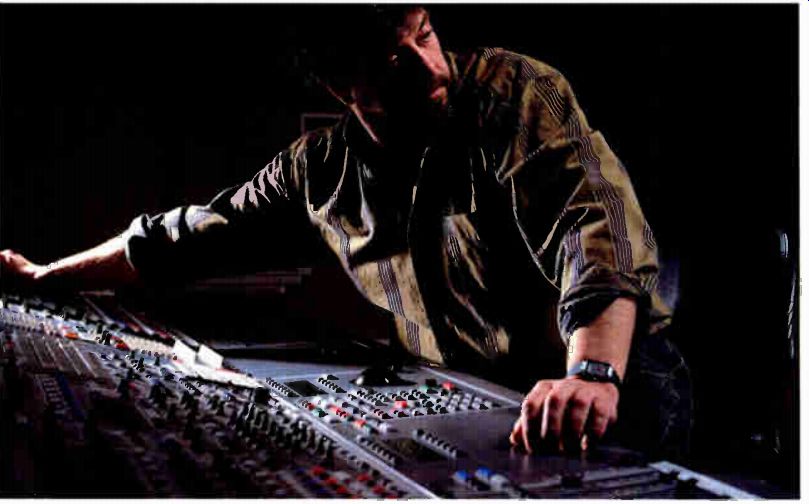

Top:

The one and only Abbey Road Studios, taken just in front of the famous

crossing and the 24-hour flash of tourists’ cameras. Bottom: Abbey

Road’s Penthouse Studio, flanked by five B&W Nautilus 801 loudspeakers,

making up perhaps the ultimate surround system.

“In the early days, stereo was ridiculous. Every guitar solo on every album was panned around from left to right and it was just nonsense. Stereo has grown up in rock music. As more tracks became available, people have learned to use it more effectively than perhaps they did.”

“In itself Alan, isn’t there very little that’s in true stereo, as in two microphones in a space... ?“

“That is, I think, something missing from rock: the actual ‘naturalness’ of stereo miking. I’d like to experiment further with more distant genuine stereo miking in an acoustic environment.”

“I suppose some people would say that ‘naturalness’ isn’t really necessary in rock.”

“Yeah, but it’s not so much being natural, it’s creating space. There’s some thing very different between an instrument being exactly there, and it being there with air around it, feeling the space. I think they haven’t — even with electronic processing for stereo sound — they haven’t quite got the general vibe that is created by a stereo mike, or a microphone picking some thing up with ambient mikes in the distance.”

“Traditionally, for audiophiles, the ultimate is to recreate a sense of live musicians in a room, whereas rock music maybe isn’t necessarily sup posed to be a one-to-one representation of people standing in a room playing...”

“In fact, even in the very earliest days of Bill Haley and the Comets, it was never any thing where you could say, ‘This is five guys playing,’ because they were amplified. If you actually heard them playing in the room, it would sound dreadful. So the whole concept is cheating the audio by means of microphones and amplification. Even the fashion for these so-called ‘un plugged’ things is still very rarely what it purports to be.”

“Is the approach, then, to just sort of make a soundscape from your imagination?”

“I think that’s one of the great satisfactions of being a record producer. You can sort of conjure up in your own mind what you think some thing should sound like, and if you can achieve it, then it’s the best feeling in the world. I think writing for an orchestra would be so satisfying. You know what’s at your disposal, you know what the textures are, and you can achieve it by literally writing it down. Whereas, when you’ve got a much broader palette, if you like, of sounds at your disposal — electronic sounds, vocal sounds, and so on — the possibilities become a great deal larger. Perhaps it’s more difficult to completely interpret the dream, if you like.”

“As far as creating space, how is working with the added dimension of surround?”

“Well, of course, your possibilities open up even more. You not only have a single soundfield, you have effectively four sides of the room to play with, and in addition you’ve got all the space between the speakers and the center of the room. In practice, however, if you have the sound emanating from four speakers, it’s likely to become cloudy, whereas if it’s coming from one speaker or a point in between two speakers, it’s likely to have greater clarity. That’s just a function of acoustics in a room, I think.

On my album, I stuck pretty much exclusively to the outside of the room, and nobody actually ever said ‘there’s a huge hole in the middle.’

“This next piece I’ll play is per haps a more raucous approach to surround. They said, ‘What have we got? If it’s on a track, we’ll stick it in one end of the room...”

Parsons was referring to “Babylon Sisters,” from Steely Dan’s Gaucho. The audio quality of that disc on that dream system was stunning, and its surround reinterpretation, with 360 deg clear separation of sounds, was quite compelling. It was neat.

“I’ll play you one off my album. It starts with a solo voice and acoustic guitar, and you think to yourself, ‘What can you possibly do with a solo voice and acoustic guitar?’”

“Blue, Blue Sky” from On Air begins with Eric Stewart (from 10cc) strolling the perimeter of the room, alone, among ambient birdsongs. When the song suddenly broke into a full chorus with full surround instrumentation, the effect was staggering. Apparently, this is a favorite demo tune for DTS. I can see why.

“I think I’m getting it, Alan. It’s very involving. And walking around the room, it doesn’t really feel like you’re walking away from the music. It surprised me how much I liked the Marvin Gaye, too.”

“Well, it’s just really encouraging to know that you can breathe new life into these. A dream of mine would be to commit the ultimate sin, which would be to take all of Phil Spector’s old stuff and do it surround.” [

“But does it need to be done? Isn’t it perfect as it is?”

“If I’m not allowed to do it, I should just remake them all. I’ve always had a secret wish to remake ‘Be My Baby.’ Just the whole ‘wall of sound’ thing in surround would be great. A contradiction in terms in itself, isn’t it? He was always a mono guy, and he had the Wall of Sound — that suggests a monstrous space.”

“Hey, why not? You know, this surround experience seems very different from being in front of the speakers and concentrating. I can imagine wanting to just sit in my easy chair after a long day’s work with a drink in my hand, just letting it wash over me.”

“I think that’s the way it should be. Like I said, I think music is often a background environment, so why not in crease the background of experience by having more speakers? I think audiophiles are missing out on something which they have rejected for the wrong reasons. A lot of them perhaps remember the farcical situation that we had when Quadraphonic came out. But this is genuine discrete six- channel, it does work, and it sounds good. Not enough people know that you can buy CDs DTS-encoded, and it’s just a CD. Whereas audiophiles in particular seem to be waiting and waiting for 24-bit/96kHz. What I like about this is it’s now, and anybody with a home theater and a DTS decoder can play this now.”

“As far as the end user, it’s a lot more difficult to set up a good surround system in a room...”

“I think, as a producer of surround, you have to be aware of the mistakes the consumer is going to make. The grim truth is that you can’t get the consumer to wire his speakers in phase, so, I mean, what the hell is he going to do with six channels of audio? I’ve heard of people walking into an audio shop ... ‘So you’ve got six speakers with this system? That’s great — I can have one in the kitchen, one in the bedroom...’”

Having finished with our listening session at the studio, we popped into Parson’s SUV for a spin ‘round to his home, listening to a Crowded House CD along the way.

“I thought they were the best thing for years — the kind of music I can relate to. Which isn’t the case with an awful lot of modern bands. Cars are a great environment for music. I would say the vast proportion of music I get exposed to is in my car. ‘Roll on, surround radio,’ is all I can say, because surround in a car is brilliant.”

Parsons’ home system is certainly modest in comparison to what he listens to at work. A cabinet hides a Marantz CD player, Yamaha turntable, and an Akai integrated, while his diminutive Gale loudspeakers (only two) are hidden down by the baseboards.

“Do any of the musicians you’ve interviewed have audiophile systems, Rick?”

“Not really. Except for Branford Marsalis and Charlie Haden, both of whom have Linn turntables.”

“I used to know [Linn’s] Ivor Tiefenbrun, and I correspond with him once in a while. He’s one guy who I think holds the key to what hi-fi is.”

“He’s quite a character.”

“Oh, he’s a great character. I wish he was in pro audio, because he would tell us to measure things that we’re not measuring.”

“What’s your take on LPs, Alan?”

“I find it hard to take seriously a medium where, as the pickup reaches the center of the disc, your top end is severely threatened. I think vinyl lovers often forget that.”

“Our friend Ivor might have a different opinion.”

“Yeah. ‘Increased warmth,’ he would call it.”

“Your records have been released in audiophile editions, half-speed mastered by Mobile Fidelity, gold CDs, and so on. What do you hear in those releases?”

“To be honest with you, I’ve never really investigated it, which is perhaps a true indication that I’m not an audiophile. As long as the songs are in the right order and they sound good, I’m happy.”

“It’s funny, Alan. One of the ways I got started as an audiophile was with Japanese pressings of Dark Side of the Moon and I, Robot, which I bought as a teenager. Don’t you think special pressings can enhance the quality of the music?”

“You can argue that point ‘til kingdom come. ‘How much does reproduction quality affect the quality of music?’ I think I’d say that it affects it less than a lot of audiophiles [think it] would. It’s still the same music, it’s still the same sentiment, still the same artist and source. Audiophiles would say, yes, it is better music as a result of being reproduced more faithfully. But that’s like any hobby: you become obsessive about it, you become fanatic about it. That’s what makes it work for those people. Somebody has explained to these people that, look, the figures show that this is better. ‘Oh, well, I’d better buy it then.’ It’s very dangerous for people with a lot of money. They just go so overboard on it.

“Let me ask you, Rick: Do you have experience with the more esoteric stuff the ceramic pyramids and felt pens, and oxygen-free cable?”

“Sure. And then there are the little African ebony pucks, Mpingo disks, which go on top of your components.”

“Little things that you put on top of it?”

“Yeah, you put them on top of your equipment and your speakers and you orient them just so...”

“Forgive my laughing.”

“I’m laughing too. But I’ll be dammed if can’t hear what they do. If you could hear the difference in these things, would you use them?”

“I’d probably put a gun to my head! I think it’s all quirky, witchcrafty sort of stuff”

“How would you recommend a music-lover best listen to your music?”

“A reasonable system in a good room. A good room is as important to a listening environment as anything. And I would also maintain that loudspeakers are the weakest link in any audio chain. Good speakers, good room, you can’t really go wrong.”

Alan Parson’s living room. Can you spot the loudspeaker

in this photograph?

Parson’s home system (ca. late 1998) is comprised of an Akai integrated

amplifier and Marantz CD player, along with a Yamaha turntable and Gale

loudspeakers. His home listening is predominantly background.

(Article courtesy STEREOPHILE, Jan 1999; "Rick Visits Alan Parsons at Abbey Road" (by Richard J. Rosen; written late 1998))