This section presents an overview of what is involved in learning television production. It describes briefly what the essential tools are, and how we should go about using them for optimally effective communication. In general, the presentation of these tools and their use in this section follows the same sequence as the subsequent sections.

Television production is a process that involves the use of a rather complex machine and the coordination of a team of production specialists. The general, and so deceptively simple, division of television production into hardware and software, and hardware and software people, is both misleading and counterproductive. Regardless of whether you will eventually spend most of your time operating a videotape machine or writing television scripts, you will need to know rather intimately the basic elements and workings of the machine that translates the communication idea into a television program. Television is not just a pipeline through which the software is pushed by the hardware people; rather it is a creative process in which people and machines interact to provide the viewer with significant experiences.

Television production therefore requires an intimate knowledge of the creative process-of how machines and people interact.

To learn television production is not an easy task. The major problem is that you should know everything at once, since the various production elements and activities interact and depend on one another. Since nobody can learn everything at once, we are more or less forced to take up the production elements step by step. As in any other craft or art, we need to know what tools there are before we can hope to use them effectively. The following sections will, therefore, describe the major elements of the television machine, such as the cameras, lighting instruments, and microphones, what they can and cannot do, and how they can best be used for the most common production tasks. The coordination and integration of these elements and production activities are described in the sections on television directing and producing.

In order to provide you with an overview of television production, we will briefly outline (1) what the tools are, and (2) how they are used.

What the Tools Are The most obvious production element, the camera, comes in all sizes and configurations. Some are so small that they can be easily carried and operated by one person, while others are so large and heavy that they need at least two people just to lift them onto the camera mount. There are cameras that reproduce a scene in black and white, others in color. There are certain technical requirements that permit some cameras to be used for on-the-air broadcasting, and restrict others to closed-circuit, or non-broadcast, use.

Regardless of size and relative sophistication, all television cameras work on the basic principle of converting whatever the camera lens "sees" (the optical image) into electrical signals that can be reconverted by a television set into screen images, the television pictures.

Knowledge of this conversion is essential for understanding several other production elements and procedures--lighting, for example--which facilitate this process.

Television (meaning "far-seeing") is a type of photography (meaning "writing with light"). As such, the lens is as important a part of the camera as it is of the still or film camera. In all photography, the lens selects part of the visible environment and produces a small optical image of it.

This image is then transferred either onto a film or, in the case of television, onto a special camera pickup tube. Lenses that can take in a large vista are said to have a wide angle of view. Others are said to have a narrow angle of view. They permit you to see less of the vista but bring far objects to close range, very much as good binoculars do.

Other lenses (zoom lenses) permit you to move continually from a wide vista to a closeup view without moving the camera. The lens, therefore, is important because it determines to a large extent not only what the camera sees but also how it sees.

The mounting equipment is important especially for the heavy studio cameras. By being able to move the camera about the studio floor, turning it into any direction, and raising and lowering it, you can not only follow a moving object reasonably well but also change the point of view in order to dramatize a particular shot or scene.

Like the human eye, the camera cannot see without a certain amount of light. Indeed, since it is not objects we see but merely the light that is reflected off them, it stands to reason that a manipulation of the light that falls on the object will influence the way in which we finally perceive it on the screen. Such manipulation is called lighting. A thorough knowledge of the various lighting instruments, what they can and cannot do, is of course a prerequisite for effective television production. Without good lighting, the best of cameras will not be able to produce effective screen images. At the same time, all the lighting in the world will not help you to achieve the desired television picture if the camera cannot "see" well, because it is either badly designed, badly adjusted, or badly used. The lighting techniques must be adjusted to the demands of the scene and also to the technical demands of the camera.

Although the term television does not include audio, the sound portion of a television show is nevertheless one of its most important elements.

Television audio not only communicates precise information, but also contributes greatly to the mood of the scene, that is, how we feel about what we see. In order to realize the value of the information function of sound, simply turn off the audio during a newscast. Even the best actor would have a hard time communicating news stories through only facial expression and an occasional film clip. The aesthetic function of sound (to make us perceive, or feel, an event in a particular way) becomes quite obvious when you listen to the background sounds during a police story, for example. The squealing of tires during a high-speed chase is real enough; but the rhythmically fast, exciting background music that accompanies the scene is definitely artificial. After all, the police car and the getaway car are hardly ever followed in real life by a third vehicle with the orchestra playing the background music. But we have grown so accustomed to such aesthetic intensification devices that we certainly do not consider them strange bedfellows for the actual event. In fact, we would probably feel dissatisfied if they were missing from the scene.

The relative complexity of the video portion (the pictures) of television production (camera, lighting, scenery, editing, and so forth) has seduced many a production person into neglecting the audio portion. Thus, you will find that television audio is often inferior in quality. In order to remedy this all-too-frequent discrepancy, you should pay special attention to the audio production elements.

First, the microphones. You have to know not only the various types of microphones available, but also which ones will perform optimally in various contexts. One type that performs extremely well for the pickup of a symphony orchestra may be almost useless for the outdoor pickup of a marching band. A small microphone that works quite well for the voice pickup of a newscaster may be less than desirable when used on the drums of a rock band.

Second, the audio console. It permits the mixing of several sound signals, whereby each sound input can be separately controlled in loudness and tone quality.

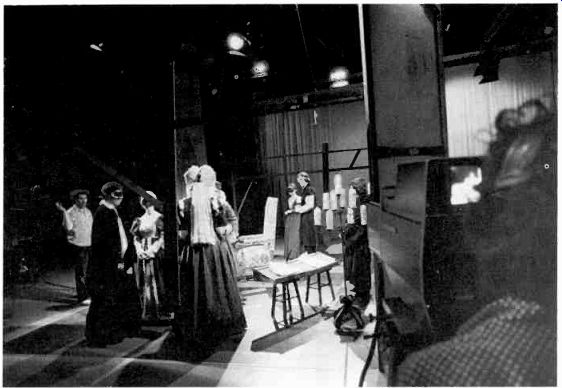

Fig. 1.1 Television production requires the coordination of a team of specialists

and a variety of complex equipment.

Performers, and production and engineering personnel, must all work in harmony in order to achieve the desired effect.

Third, the various audio recording and playback devices are as important to a successful television production as are the cameras and lenses. The more you know about the sound equipment and its use, the easier it will be for you to operate the equipment and to achieve the desired communication effect relative to the video.

Although television production can occur practically anywhere, the studio still provides maximum control. Together with its control room and master control, the studio is equipped in such ways that the various production elements and activities can be used and coordinated effectively and efficiently. When shooting outdoors, for example, you are generally dependent upon the available light, even if there is additional lighting, such as the large stadium lights during a football game.

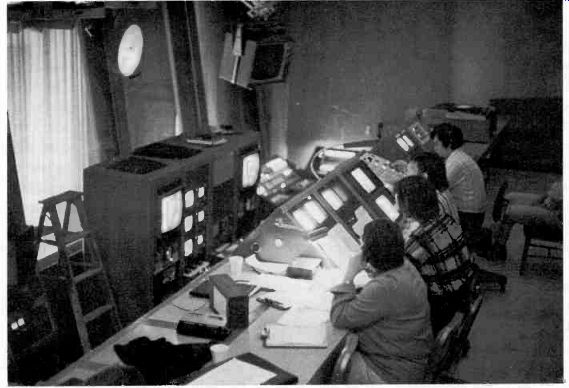

In the studio, the amount of light, as well as the way in which the lights are used, can be carefully controlled. The camera movement and picture control, the audio setup and audio control, and the sequence of the pictures and sounds all are afforded maximum flexibility and control. The various audio and video recording and playback devices are readily available. No wonder, then, that a great deal of television production still originates in the studio, or at least from control centers that are built into large vehicles, the so-called remote trucks. (See 1.1 and 1.2.) Most shows you see on television have been prerecorded on videotape or film. Although the most unique feature of television is its aliveness-that is, its ability to capture and distribute an event to millions of viewers while it is actually taking place-the control over production (the creation of a show) and programming (when and over which channel the show is to be telecast) has made videotape and film two indispensable production elements.

1.2 The actual coordination of production persons and equipment takes place

in the control room. Here decisions are made about what kinds of pictures

and sounds are to be stored on videotape or sent directly over the air.

With videotape, you can record a program (pictures and sound) and play it back immediately afterwards, or at any later time. No processing is necessary. Sophisticated computer-assisted electronic editing makes videotape even more flexible than film in postproduction activities. Postproduction generally refers to the assembly of a continuous show from prerecorded video and audio segments, or, more specifically, videotape and film editing. Videotaped programs can also be easily duplicated for distribution to the various television stations.

Videotape recorders vary in size and sophistication as much as television cameras. Some of them use 2-inch videotape for high-quality recording; some of the small, portable machines, which are no larger than an oversized handbag, use 1/4-inch tape (similar to reel-to-reel audio tape) for non-broadcast productions. The video cassette machine has simplified the recording and playback of videotape to such an extent that it is seriously threatening the dominance of 16mm film in broadcasting as well as in education and industry.

Nevertheless, 16mm film still comprises a major television programming source. Most feature films (generally distributed in the 35mm format for theater projection and network use) are reduced to the 16mm format for local television, and many television news departments still find it easier to use film instead of videotape for their local news stories. But even here the improved quality and ease of operation of the portable television camera and videotape recorder, the immediate videotape playback capability, and the relative ease of videotape editing have made videotape a serious competitor for film. Already, many stations transfer commercial or news film to videotape cassettes for more convenient on-the-air operation. Nevertheless, the film island, which contains at least one film projector, a slide projector, and a mirror system that reflects the film or slide image into its stationary television camera, is still very much a part of standard television equipment.

Successful picturization, which includes all aspects of controlling a shot sequence so that the sequence becomes a structural whole, depends on two further production items: the switcher and electronic videotape editing equipment. The switcher permits instantaneous editing; the electronic editor, the postproduction assembly of videotaped program portions.

The switcher, which consists of several rows of buttons, allows you to select pictures from a number of video inputs (from such picture sources as camera, film, slide, or videotape) and assemble them sequentially through transition devices, or simultaneously, as in the superimposition of two pictures. The most common transition devices are the cut, an instantaneous change from one image to another; the dissolve, the temporary overlapping of two images; and the fade, whereby the picture either goes gradually to black or appears gradually from black. The most common simultaneous combinations of two pictures are the superimposition, whereby one picture is electronically laid over another, and the key, whereby one picture is electronically cut into another.

If your material has already been prerecorded on videotape, you can achieve the proper picture sequence through postproduction editing (in contrast to the production, or instantaneous, editing with the switcher). This involves a more or less sophisticated electronic editor, which is part of the videotape machine. With the electronic editor, you can assemble a great variety of videotaped program portions onto another videotape without having to splice them together physically, as is customary in film or audiotape editing.

Other important production elements are scenery and properties, which are both used for creating a suitable physical environment (for example, a living room with furniture, pictures, ashtrays, flowers, lamps), and television graphics, which includes title cards, charts, and graphs.

How the Tools Work

The mere knowledge of what tools are available or necessary for television production is not enough; you should also learn how to use them for a variety of production tasks. A guide can serve only as a guide in this endeavor. After all, the most practical way of learning how to use a tool is by working with it, not merely by reading about it. You should, therefore, consider the portions of this guide that describe the use of the equipment as a basic grammar of television production, a road map, and not as a substitute for actual production experience. We would certainly experience intense discomfort if everybody were content with reading cookbooks without ever engaging in the process of cooking.

However, it would be equally wrong to assume that we dispense entirely with the theory of production and merely rush into the studio to learn everything "from the bottom up." Reinventing the wheel through discovery may be a pleasant enough experience, but it is also a wasteful one and, in the end, utterly inconsequential. What we need to do is to learn quickly that there is such a thing as the wheel, and then find out how it can be used in order to contribute positively to individual and social growth. The same goes for television production. Why should you not benefit from the countless trials and errors of previous productions and from the principles and practices that have proved successful? Indeed, once you have learned these principles, you can go beyond them, or ignore them altogether if your communication purpose requires such extreme steps. In any case, don't be afraid of using the conventional approaches. They have become conventional because they work most of the time. Triteness and clichés in production are more frequently caused by the lack of a clearly defined communication purpose, by the lack of having something important to say, than by the conventional use of the medium. Achieving eloquence and style in production does not mean necessarily that you have to invent entirely new techniques, but rather that you use the production tools in such a way that the viewer perceives a significant communication experience. You don't have to put the speaker upside down in order to entice the viewer to stay tuned to your message; simply give her something significant to say, and then let the viewer see and hear her as clearly as possible.

The sections on producing and directing offer some of the principles that contribute to the choice of television production elements for a certain communication task, and to the coordination of these elements in order to produce the desired effect.

And yet, in a time where effective mass communication has become essential for personal and social growth, we should not and cannot remain content with either the available tools or their conventional use. It does not really matter whether the need for non-broadcast television communication or the search for new art forms has led to the development of self-contained, portable, easy-to-use television equipment, or whether the development of the small equipment has led to new communication approaches. In either case, the small equipment (such as portapaks and other relatively inexpensive video cameras, and recording and playback devices) provoked a change in the use of television that is aptly called the video revolution. Free from the pressures of large commercial concerns, or equally institutionalized noncommercial television stations, the video artist went about his or her experiments in a refreshingly new, though often naïve, way. While the commercial video engineer tried desperately to produce a picture free from electronic interference, the video artist often purposely produced such interference in order to intensify the expression of his ideas. As in any other development of new techniques, the line between when the ideas were intensified by electronic distortion or other unusual production techniques and when they actually suffered from such treatment was not always as clear-cut as one would have wished.

But the real worth of such video experiments was to show to the producer and consumer alike that the television medium was anything but neutral, that it was not merely a pipeline of ready-made messages, a mere distribution device, but that it could be used effectively in the formulation, in the building, of the message itself Thus, the so-called program content was only part of the message; the other, and equally important, part was the use of the medium-specifically, the television production techniques.

With this in mind, you are certainly encouraged to experiment with the medium, occasionally to break the rules and conventions of production, and to try out new ways of using the tools, if the communication so requires. But such experimentation will remain satisfying and effective only after you have learned the basic use of the production tools-the basic techniques of television production.

Summary

Whatever part you play, you should realize that television production is team work. Even with a portapak, you will find that you need somebody else to help you with the cable, or to hold the microphone. The more complicated the equipment gets, the more people it takes. In fact, the major task of television production is working with people, the ones in front of the television camera (talent) and those behind (production and engineering crews, directors, and other station personnel). (See tables 14.8 and 14.10.)

Even the most sophisticated television production equipment cannot make ethical and aesthetic judgments for you; it cannot tell you exactly what part of the event to select and how to frame it for optimal communication. You have to make such decisions, within the context of the general communication intent and through communication with the other members of your production team.

In television production, then, you are expected to know how to work with other persons, in order to generate creative ideas and solve problems.

Television production is a process that involves the use of complex equipment and the coordination of a team of production specialists. A knowledge of the elements, or tools, of the process and how they work is the other essential task. These tools include the camera, lenses, mounting equipment, lighting instruments and the techniques of television lighting, audio, the studio and its control centers, master control, videotape and film, picturization (which means the controlling of a shot sequence through instantaneous or postproduction editing), scenery, properties, television graphics, costuming, and makeup. In essence, knowing the tools and how a production team manipulates them for a specific communication purpose is what television production is all about.

To this end, the following sections of this guide are designated.