In this section we examine a production activity and its major types of equipment, called (misleadingly) "video." Video refers to a variety of non-broadcast television production activities by individuals or small groups outside the broadcast industry. Whatever the production purpose may be, the video functions are one of these three, or a combination of them: (1) the camera (representing the whole video gear) looks at, fulfilling primarily an observational function; (2) the camera looks into, providing an insight into an event; and (3) the camera creates, producing a screen event that has no live counterpart anywhere.

The event is the electronic screen and speaker image.

The equipment (cameras and videotape recorders) is called small format in contrast to large-format broadcasting equipment. Most video productions are done with small, highly portable cameras and videotape recorders. Though lacking broadcast quality, this equipment produces amazingly good pictures and sound, especially when used for closed-circuit distribution. We will describe, therefore, the most common small-format equipment and its principal operations.

When we speak of television production, we tend to think immediately of broadcast operations. But a major portion of television production is done for non-broadcast, or closed-circuit, communication.' There is a wide array of non-broadcast television. Closed-circuit television can be used to watch parking lots or hospital beds, and it can be used to distribute full-fledged productions to large audiences in theaters. Television programs are produced to instruct art or chemistry students, or to show a new bank teller how to cash a check.

Except when it serves a merely observational function (such as watching a parking lot), the production techniques for closed-circuit television are usually not drastically different from the ones used in broadcasting stations. The equipment may differ-you may have small monochrome cameras and a simple switcher rather than the latest color equipment, and you may work out of a converted classroom rather than an elaborate studio-still, the basic steps are quite similar to the ones we have described in the preceding sections. In many cases, the mode of transmission (open or closed-circuit) influences the production method not at all, or perhaps only to a slight degree. But there is one use of television that is sufficiently different from the broadcast-type production to warrant special attention. This is what is ordinarily, and somewhat misleadingly, called video.

Video generally refers to the use of small-format television equipment by individuals or very small groups to satisfy their creative urge, or to record their immediate experiences for an equally immediate audience-friends, family, close community.

[[1. Robert K. Avery, "Telecommunication Education at the University Level: A General Status Report" (University of Utah 1974). ]]

============

AGC Automatic gain control. Regulates the volume of the audio or video automatically, without the use of pots.

Closed-Circuit Distribution of audio and video signals other than broadcasting. Includes direct video and audio feeds from the camera and the audio board, from the videotape recorder into a monitor, or the RF (radio frequency) distribution via cable.

Deck Or videotape deck.

Short form of videotape recorder.

EIAJ Abbreviation for Electronic Industries Association of Japan. Established the EIAJ Type No. 1 Standard for 1-inch helical scan videotape recorders. In general, the standard assures that any monochrome tape recorded on one such recorder can be played back on any other monochrome or color recorder, and any color tape can be played back on any other color VTR, provided that they meet the EIAJ Type 1 Standard.

Impedance A type of resistance to the signal flow.

Important especially in matching high or low-impedance microphones with high or low-impedance recorders. Also, a high-impedance mike works properly only with a relatively short cable (a longer cable has too much resistance), while a low-impedance mike can take up to several hundred feet of cable. Impedance is also expressed in high-Z or low-Z.

Monitor/Receiver A television receiver that can reproduce direct video and audio feeds (from the VTR, for example) as well as signals that are broadcast on a channel.

Portapak Formerly a trade name of the Sony Corporation, for a highly portable camera and videotape unit, which could be easily carried and operated by one person. It now refers to all such equipment, regardless of manufacturer or model.

RF Abbreviation for Radio Frequency, necessary for all broadcast signals, as well as some closed-circuit distribution.

Small Format

Refers to the small size of the camera pickup tube (usually 2/3-inch) or, more frequently, to the narrow width of the videotape: 1/4-inch, 1/2-inch, 3/4-inch, and even 1-inch (although 1-inch is often regarded as large-format tape). Small-format equipment (cameras and videotape recorders) is actually very small in size and highly portable.

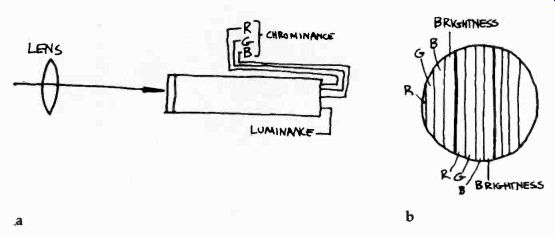

Stripe Filter

Extremely narrow, vertical stripes of red, green, and blue filters that, repeating themselves many times, are attached to the front surface of the camera pickup tube. They divide the incoming white light into the three light primaries without the aid of dichroic mirrors.

Video

Non-broadcast production activities and the use of small-format equipment for a variety of purposes. Usually the equipment includes a portable camera, a microphone, a videotape recorder or video cassette recorder, and a monitor.

=============

With small-format television equipment, you can now produce, shoot, play back, and even edit your own television program. The small-format video cassette or cartridge makes it possible for you to watch a program anywhere, at any time, and as often as you wish; the option is no longer with the sender (the television station), but with the percipient. The introduction of relatively inexpensive, easy-to-operate equipment has, indeed, caused a quiet but significant communication revolution. Television, or rather video, has become the province of the individual. The various manifestos of the early video artists and communicators are ample proof that these pioneers were very much aware of this revolution.2 Video is providing, or at least has the potential for providing, programming that is a true alternative to that of the broadcasting stations. Video can serve small, immediate community or even individual needs. Video can be used to explore the graphic potential of the television screen, to let a patient see himself or herself as part of a therapy session, or to inform us via cable of the giant sale at a corner supermarket. Video can furnish the community access to television way beyond what the open-circuit broadcasting station has to offer-not because the broadcaster is unwilling, but because his machinery is not geared to service the uninitiated amateur.

[[ 2. See early issues of Radical Software. ]]

--------

17.1 Small-format television equipment refers to the small-image format of the camera pickup tube in small portable cameras, and the narrow width of the videotape (from 0.25-inch to 1-inch).

----------

The users of video are so diversified in approach and goal that it is hard to find a common thread. And this is exactly its strength-to be free from tradition. Nevertheless, two types of users can be identified rather easily: (1) the video artists, who see in the machine a new tool for aesthetic expression, and (2) community communicators, who want to reflect (often rather naively) the various life styles of their community. While the former group produces abstract images through video feedback or other planned manipulation of the scanning pattern, the latter videotape anything that happens around them, from people preparing breakfast to the local school board meeting. Since communication, especially video communication, becomes the more effective and formative the more everyday experiences are clarified and intensified into precise messages, the two groups would profit from pooling their experiences (and sometimes they do). Small-format equipment, like all television equipment, must be used with skill, understanding, and empathy. You need to know the potentials and limitations of your equipment in order to make it work for you instead of against you.

And there we have arrived at exactly the point that was made in the beginning of this guide: in order to be an effective, creative communicator, you must know the communication tool; you must know how to work the machine so that it becomes a true extension of yourself, rather than a message-distorting intermediary.

As soon as you begin to clarify and intensify the experiences around you with a specific medium, such as small-format television, and convey them to your friends or fellow community members, you are acting as a communicator, as an artist, as a molder of opinion. Hence, you cannot help but realize that you are burdened with the ultimate responsibility of every serious artist and communicator: to contribute to positive social change, to help people become aware of themselves, to live full, happy, free, and responsible lives.

In general, the basic production approaches that we discussed previously, such as the statement of the process message objective and the fulfilling of identified medium requirements, are still valid in respect to small-format television.

However, there are three points that merit discussion, without infringing on your creative use of video. These are (1) basic video functions, (2) basic small-format equipment, and (3) basic operation.

Video Functions

The camera (representing the whole video and audio gear) can look at, look into, and create. Let's take these three functions, which can guide the process message objective, one at a time.

Camera Looks At

When the camera looks at the event, it strictly observes as objectively as possible. The video (and, of course, audio) acts basically as a recording device for a specific event. Since the camera is nevertheless innately selective (it cannot see everything at once), you still have to make certain decisions about what to include and what to leave out in your recording. You should, therefore, try to select the essential parts of the event for your video experience. When recording an athlete so that he can see himself after the performance, you use video to look at. Video is often more effective than film in this function, since you can play back the event immediately after it occurred. For example, by videotaping your girl friend running over the hurdles, you can show her immediately after each run how she did, what she did right and what she did wrong. She then can go back and correct the mistakes as shown on the videotape.

With film, she would have to wait at least one day before she could see what she did wrong, with no chance for immediate feedback. Video, thus, can contribute to a learning process which otherwise would be difficult to achieve.

The recording of events for archival purposes or easy distribution is another important looking at function.

17.2 When looking at an event, the camera merely reports it as faithfully

as possible. The camera takes on an objective point of view.

17.3 When looking info an event, the camera scrutinizes it from a variety

of points of view. The camera looks at the event at close range. The camera's

viewpoint becomes introspective.

17.4 When the camera creates, it takes the outer event simply as raw material

for the electronic manipulation. The actual event can exist only as a screen

event.

Camera Looks Into

When the camera looks into the event, it scrutinizes from an extremely close point of view. Consequently, it reveals aspects of the event we ordinarily would not, or could not, see. Let's take modem dance, for example. If you look at the event through the camera, you simply record the dancers' movements as well as possible. The camera observes the dance as someone who is watching it in the theater (see 17.2). But if you use the camera to look into the dance, you select and intensify only some of its essential parts (see 17.3). Perhaps we will never see the dance exactly the way we see it in the rehearsal hall or on stage. But we will see portions of arms, bodies, hands, feet, revealing the basic movements, the basic structure of the dance, and intensifying the essential rhythm.

In sports we would no longer watch how somebody takes the high hurdles, for the purpose of studying the athlete's technique, but we would instead fasten on the skill, the grace, and the beauty of the motion. Or, perhaps, you could use your camera in such a way that the screen event reveals the incredible physical and psychological strain of such a race.

Note, however, that we are still using the event as the prime material for the video experience.

We do not go beyond the event but simply into it. We are probing its essence.

Camera Creates

When we create a video event, we use the external event, such as the dance or the hurdler, simply as raw material for our electronic manipulations. The event as created by the camera exists nowhere except on the screen. The screen event is the primary experience. For example, in the modem dance you would use the dancers as space manipulators, to define screen space, or simply as energy sources for your electronic manipulations.

Through keying or matting, a dancer moving by may become an abstract pattern in motion, which, nevertheless, is caused by the energy of the dancer herself. (See 17.4.) Since you are now concerned mainly with the electronic manipulation of the screen image, you can do away with the camera altogether and manipulate the scanning pattern in the monitor directly by feeding in any number of external energy sources, such as the audio signal from the accompanying music, or the energy generated by a video synthesizer, similar to the Arp or Moog synthesizers in the audio field.

In reality, these distinctions are not always as clear-cut as they might appear in this discussion.

The three medium functions frequently overlap to some extent. However, a clear understanding of each function will certainly help you in your basic approach to the subject matter, in the formulation of the process message objective. If you want just to report an event, such as the planting of new trees along the neighborhood street, you look at it from a rather detached point of view.

If you want to show the importance of these trees for beautifying the neighborhood and for helping to make people happier by their presence, then you should move your camera into the event, and capture the reactions of the people looking at the trees, touching the trees, putting their hands into the soil while planting the trees. If you want to demonstrate the symbolic importance of the trees as bearers of new life and hope, as elements that counteract decay, then you may want to create an appropriate experience with the camera based on the energy of the tree-planting event, such as leaf patterns, the movement of groping hands keyed into the fresh branches, and so on.

It is quite likely that your process message objective allows any one of the three camera approaches within a single program. Your coverage of the original event should, therefore, be handled in such a way that you have all three options open in the postproduction process.

As with producing a program for on-the-air presentation, the translation of a program objective into the video and audio images requires that you know what the equipment can do and how to make it work. We will, therefore, briefly describe some of the major small-format equipment and its operation.

----------------------

17.5 When working in video, you will generally have no one close by that

can undertake minor or major equipment repairs. Consequently, you will either

have to learn how to do some of the maintenance and even minor repair jobs

yourself, or take the defective equipment to a factory service center or a

manufacturer-authorized service center. It is a good idea to buy the equipment

from a store that has an authorized service center, since you can always bring

it back to the same place for repairs.

----------------------

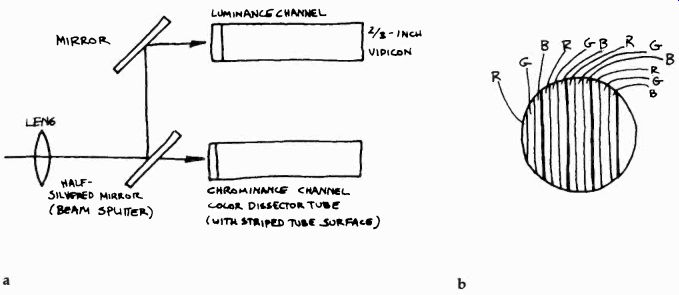

17.6 Schematic of Two-Tube Color Camera: In the two-tube color camera, one of the tubes takes care of the black-and-white picture information (luminance); the other with the color information (chrominance). As in the larger, three-tube color cameras, the incoming light is split and directed into the two tubes. The luminance tube consists of a %-inch vidicon and acts like a black-and-white camera. The chrominance tube (or color dissector tube, as it is sometimes called) has on its target area extremely narrow stripes of red, green, and blue color filters, which split the incoming light into three additive primaries. This filter is called the stripe filter. The two signals are then combined with each other (matrixed) exactly as in the bigger studio cameras.

------

17.7 Schematic of One-Tube Color Camera: In the one-tube color camera, the

target area of the tube is striped with a four-way filter, which takes care

of the chrominance and luminance information.

The filter consists of sequential red, green, and blue stripes, plus a fourth stripe that controls brightness.

Small-Format Equipment:

Small-format television equipment comes in a dazzling variety of names, sizes, sophistication, and quality. Every year, new stuff is produced that is supposed to outperform the old. Any attempt to describe small-format cameras and video recorders in detail would be not only futile but not really helpful for you in learning how to manage small-format video production. Let us, therefore, concentrate on a few major equipment items. These are (1) the small-format camera, (2) the portapak, (3) audio equipment, (4) videotape recorders, (5) playback monitors, and (6) lighting.

The Small-Format Camera

As with any other television camera, the small-format camera consists of a pickup tube, or pickup tubes, electronic accessories (with a built-in CCU or a small, portable CCU unit), a lens, and a viewfinder. As mentioned before, the camera is called "small format" because of its small-sized pickup tube.

The monochrome camera has as its pickup tube a 1.25-inch vidicon. Depending on the sophistication of the electronic circuits, the camera can range in size from an average-sized book to a shoebox.

The color camera works with either one or two color pickup tubes.

Since the pickup tubes are small format, even the color cameras are not much larger than their black-and-white equivalents. Unfortunately, the quality of the color in the two- or one-tube cameras is still far below that of the three-tube studio cameras. However, for non-broadcast purposes and especially for experimentation, the portability and relatively low cost of the small-format camera by far outweigh the quality handicap. You should realize that quality becomes a major concern primarily when you broadcast the camera's signal. If you distribute it closed-circuit (from camera to cassette recorder and back to a monitor), the picture information loss is minimal and the color pictures produced by the small-format camera look amazingly good.

Most small-format cameras have a zoom lens with a 4 : 1 or 5 : 1 zoom range, and a maximum aperture anywhere from f/1.2 to //2.0, with f/1.9 being the most common.

The zooming is done right at the lens, with no other zoom controls (such as cables or rods) necessary. The zoom lens has a C-mount and is, therefore, interchangeable with fixed-focal-length C-mount lenses. You may find that for some shooting assignments the zoom lens is not the most convenient to use. Zooming in to a TCU while handholding the camera rarely works out well. Even before you have arrived at the TCU, your picture will wiggle and jump because of the narrowing angle position (longer) of your zoom lens. A wide-angle fixed-focal-length lens (such as a 10mm for the 74-inch tube format) may sometimes prove much more satisfactory for portable work than a zoom lens. The wide-angle lens permits you to walk right into the scene (you will remember that it has a large depth of field) without undue focus problems. Furthermore, it minimizes rather than emphasizes camera wiggles, unless you get extremely close to the object.

Most small-format cameras have a small electronic viewfinder, which, in some cases, is magnified optically for comfortable viewing. On some cameras (such as the portapak), the viewfinder also acts as a playback monitor when you are checking a videotape recording.

Some small-format cameras have a pistol grip for easier "shooting." You may, however, find that this is not an ideal camera handling device. Although the camera is generally light, holding it by the pistol grip for any length of time will quickly tire your hand and arm. Many experienced camera operators prefer to rest the camera directly on their hand without the aid of the pistol grip, or to construct a shoulder harness, similar to the harnesses for film cameras. Most pistol grips are easily removable from the camera base.

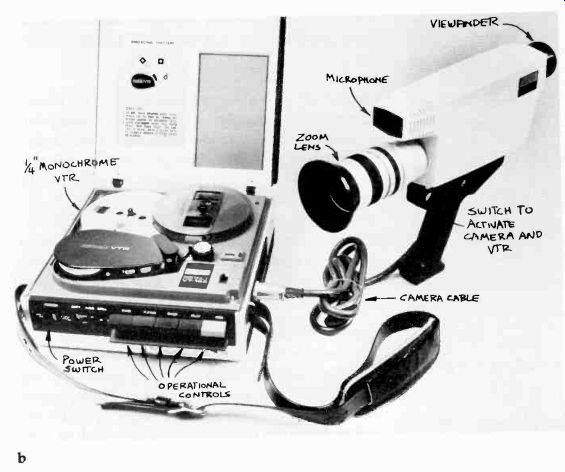

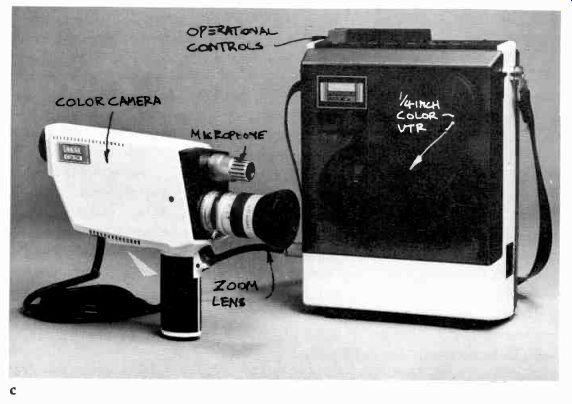

17.8 (a) Sony Video Rover. (b) Akai VT-120 System. (c) Akai VTS-150 Color

System.

A sturdy tripod is still as important a camera mount for the small-format camera as it is for the heavier studio cameras.

[[3. The first small-format camera-recorder units were called Portapak by the Sony Corporation. Later, Sony changed the name to Video Rover (registered trademark). However, video people still like the name "portapak" and use it almost exclusively to denote any portable small-format camera-VTR combination. ]]

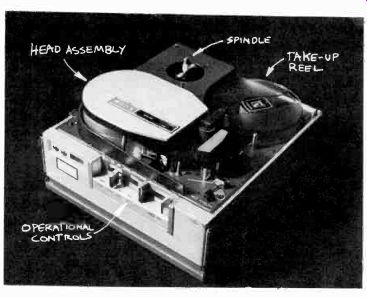

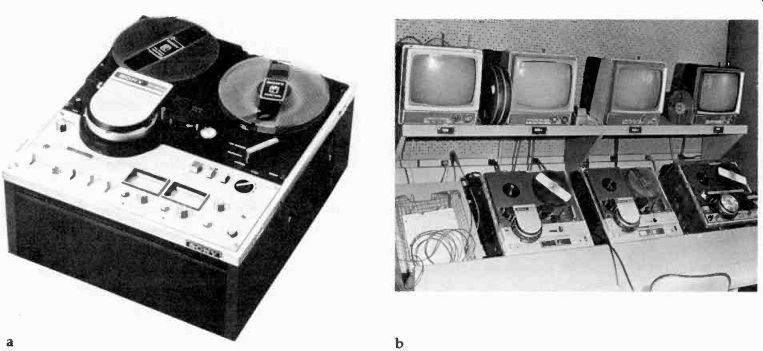

17.9 1/2-inch Videotape Recorder of the Portapak Unit (Sony).

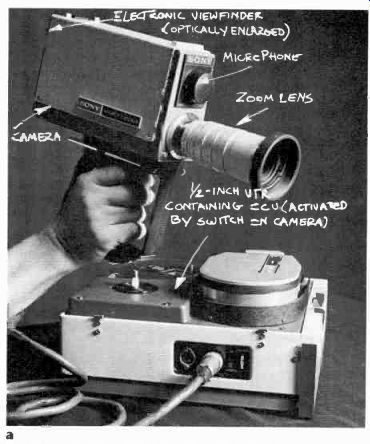

The Portapak

The portapak unit3 consists of a small portable vidicon camera usually connected to a small port-able 1/2-inch reel-to-reel videotape recorder. This camera-recorder unit has probably contributed more to the video revolution than any other single piece of television equipment. The portapak is an immensely useful instrument and, if used properly, can produce videotapes of excellent quality. Its chief virtues are complete mobility and independence of any other piece of equipment. The portapak unit can run off a battery pack (which is part of the VTR machine) or off regular 110-volt house current (which is changed to DC-direct current-in the battery charger unit). The portapak camera has a built-in microphone (some of the older models have a small mike attached to the top of the camera), with additional facilities for an external mike input at the recorder unit.

The Portapak Camera

The portapak camera can be monochrome or color. Since the color camera uses the one-tube system, it is not very much bigger than the monochrome camera. If you work in color, you will also need a tape deck that will record the color signal from the camera in color.

Most portapak cameras come equipped with a 4 : 1 (12.5mm to 50mm), /11.9 zoom lens with a C-mount. As with all other small-format cameras, you may want to replace the zoom lens with a wide-angle lens for especially mobile camera pickups.

[[4. Richard Robinson, The Video Primer (New York: Links Books, 1974), p. 13. ]]

As has been discovered by many a portapak user, the cable that leads from camera to VTR deck is usually too long when you carry the camera and the VTR unit, and too short if you want to move away from the VTR unit for some interesting camera angles.4 You may want to have the camera cable shortened, and then use some additional cable for the "independent" camera operation.

The Portapak Videotape Recorder

The videotape recorder, usually referred to as portapak deck, is a small 1/2-inch reel-to-reel model, which holds a 1,200-foot roll of videotape. With a reel this long you can record up to thirty minutes' worth of programming. This tiny portapak VTR not only records video and audio signals but also provides the electronics necessary for the camera to operate properly. The camera cannot function without the VTR unit. Figure 17.9 shows the major parts of the portapak deck.

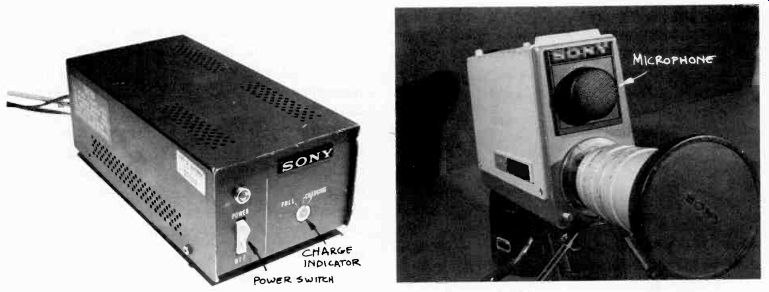

Power Supply

You can "drive" the portapak unit with rechargeable batteries that fit into the tape deck unit, or external battery packs that are adapted to the portapak power requirements (usually 12 volts DC). Or, you can use regular AC power from the household outlet, which is then changed into the low-voltage DC power through a converter located in the battery charger (17. 10). Make sure that the batteries are always fully charged before using the portapak with battery power. You should recharge them as soon as you get back from a "remote," or, better yet, every day, so that you will have full power whenever you need it. A second battery unit is almost a must if you use the portapak frequently. Not only can you recharge one unit while using the second one, but you will also extend the re-chargeability of each battery unit. Don't let a battery become completely discharged or it will not hold a recharge.

17.10 Sony AC-3400 Battery Charger and AC Adapter.

17.11 Most portapak cameras have an omnidirectional microphone attached or

built in, pointing into the direction of the lens.

Audio Equipment

Good audio is as difficult to achieve in small-format television production as it is when using studio-type equipment. Again, the quality depends almost more on how the microphone is used than on its relative sophistication. A high-quality microphone badly used will give you worse sound than a lower-quality mike used properly.

If you work with a portapak, you can use either (1) the microphone that is attached to the camera or built into it, or (2) a microphone that is independent of the camera and can be used close to the sound source, very much like the kind used for studio-type productions.

The Built-in Microphone

This omnidirectional mike points into the direction of the lens (see 17.11). As desirable as such a sound pickup device is from an operational point of view (you don't have to worry about handling a separate microphone), it is difficult to get good sound with it. Here are some of the problems: (1) Unless you work the camera very close to the sound source, thereby sticking the camera into the face of the speaker, the omnidirectional microphone will pick up many extraneous noises. (2) The automatic gain control, or AGC, which is necessary because you don't have anyone to "ride gain" (control the volume) for the built-in mike, will tend to emphasize the loud sounds, regardless of whether they are the desired sounds or just background noises. Additionally, the mike, controlled by the AGC, is subject to distortion as a result of input overload. (3) The microphone, which is attached to the camera, is sensitive to the inevitable rubbing noises and shocks connected with the handling of the camera.

When the desired sounds are general, such as music from a marching band or the screams of an excited crowd during a football game, the built-in microphone will work just fine. Whenever you need to emphasize one particular source over another, however, you will need to use a microphone that is independent of the camera, or several microphones and a mixer, very much as you would use a microphone setup in a studio production.

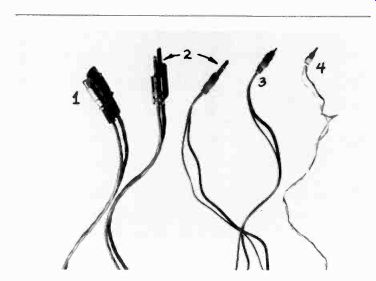

17.12 There are generally four major types of audio cable connectors: (1)

the Cannon connectors, (2) the phone plug, (3) the RCA plug, or phono plug,

and (4) the mini plug.

17.13 Impedance is also expressed by the letter Z. High-Z means high impedance

(high resistance and therefore short cable); low-Z means low impedance (low

resistance and therefore long cables).

17.14 (a) Sony AV-8650 1/4-inch Color Videotape Recorder has insert and assemble

editing modes, as well as slow-frame and still-frame capabilities. (b) Editing

Bench, using Sony AV-3650 1/2-inch Monochrome Videotape Recorders.

Independent Microphone

When using a microphone that is separate from the camera, you simply select the appropriate type (such as a lavaliere, hand mike, or highly directional microphone) and plug it into the appropriate receptacle at the recorder unit. When using an independent mike, you must watch out for two things: (1) that the microphone plug matches the receptacle at the recorder unit, and (2) that the impedance of the microphone matches the impedance of the recorder.

For all practical purposes, impedance means resistance to the flow of an electronic signal, such as an audio signal. There are high and low impedance mikes. High impedance mikes have a slightly higher output signal than low, but there is also a high resistance in the cable from mike to input (recorder); at least there is a high loss of certain frequencies. Low impedance mikes have a lower output, but also low resistance, or low loss, in the cable. While the high impedance mikes can tolerate only about a 15-foot (approx. 5m) cable, low impedance mikes can use very long (up to several hundred feet) cables with a minimum of signal loss. High-quality mikes are usually low-impedance, while home-recording mikes are often high-impedance.

The portapak microphone input is low impedance. You must, therefore, use a low-impedance mike for your independent (away from the camera) audio pickup. A high-Z mike will not work, even if its plug matches the receptacle of your recorder unit.

If you use more than one microphone for your audio setup, you need a mixer, as described in Section 7.

Small-Format Videotape Recorders

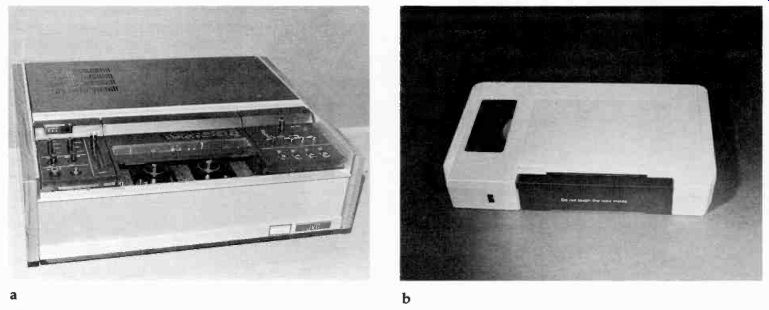

In the small-format field, there are almost as many types of videotape recorders on the market as there are cameras. As already pointed out in Section 9, small-format videotape recorders allow you to record a television signal from a television camera, a television set, or another videotape recorder. Some recorders have electronic editing capabilities, and slow and stop motion (17.14). There are basically two types of small-format videotape recorders: (1) reel-to-reel and (2) cassette.

17.15 The EIAJ Type No. 1 standard embodies some operational and electronic

standards. For example, the tape must be 1/2-inch wide; the tape speed is

always 7 1/2 ips; the recorder must hold 2,400 feet of videotape, which is

good for recording or playing back one hour's worth of programming; the audio

track is always on the top edge of the tape, the slant-track video signal

in the middle, and the control track on the bottom edge.

17.16 A close cousin to the cassette recorder is the video player, which

uses 8mm film instead of videotape for playback through a television monitor.

In effect, the video player is a small 8mm film chain, all neatly packaged

in an easy-to-operate cassette-like machine.

Reel-to-Reel Recorders

These come in a variety of videotape formats, with tape widths of 1/4-inch, 1/2-inch, 3/4-inch, and 1-inch. All are helical scan models. The more sophisticated ones have electronic editing and playback facilities for slow motion and stop motion. Some recorders record and play back in black-and-white only, while others can record and play back in either black-and-white or color.

Unfortunately, not all small-format recorders are compatible. You may find that a 1/2-inch videotape you recorded on one machine cannot play back at all on another type of 1/2-inch recorder. Some standardization has been achieved through the Electronic Industries Association of Japan (EIAJ) for 1/2-inch black-and-white and color machines, although 1-inch and 3/4-inch machines have not yet been standardized. When using EIAJ (Type No. 1) 1/2-inch VTR's, you can play a tape recorded on one machine on any other machine, with no, or only minor, playback adjustments (such as tracking). For example, you can play back a monochrome tape (recorded on a monochrome ÉIAJ machine) on another EIAJ monochrome videotape recorder, or on an EIAJ color recorder (on which the tape will, of course, appear in black-and-white). Or you can play back an EIAJ color tape on a monochrome VTR, on which it will appear in black-and-white. Or you can play back an EIAJ color tape on any other EIAJ color VTR in color.

The typical reel-to-reel recorder is small enough so that one person can carry it from place to place. But only the portapak model can be carried rather easily while the camera is in operation.

Video Cassettes

Like the reel-to-reel recorders, the cassettes come in a variety of formats, using either 1/2-inch or 3/4-inch videotape. Most of them record and play back color and monochrome. The big advantage of the cassette recorder over the reel-to-reel is the ease of operation. All you do is plug the completely self-contained cassette into the machine and press the play button. The cassette recorder will do the rest. When recording, you simply push the record button. When the tape is finished, the machine will stop itself and eject the cassette (Fig. 17.17). Some models even change up to twelve cassettes automatically.

A further advantage is that you can mail the cassette easily, just like a small package.

Whether to use the 1/2-inch or the 3/4-inch tape format depends on the quality of the machine or your particular need. Generally, the video cassette machines use 3/4-inch tape.

While most cassette recorders are designed for straight recording and playback of program material, some of the more sophisticated models have electronic editing and slow and stop-motion facilities for postproduction work.

Some cassette recorders, which are completely portable and can be used like the portapak, can hold cassettes with a maximum of twenty minutes' running time.

17.17 (a) Video Cassette Recorder. (b) Video Cassette (3/4-inch).

Most cassette recorders back themselves up about 12 seconds whenever you push the stop button during a playback. This way, when you resume the playback, the tape has time to stabilize electronically without any loss of program material. It is especially important for you to be aware of this automatic backup system if you do editing on the cassette recorder.

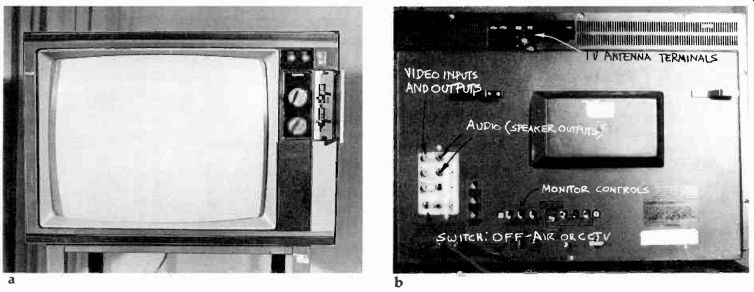

Playback Monitors

Unless you don't mind viewing your production achievements through the 1-inch viewfinder of your portapak camera, you will need a monitor for your playback.

A monitor is a television set that cannot receive broadcast programs but only direct video and audio from the videotape, or camera and microphone. Since the signals come directly from the recording and not as a radio frequency from the antenna (RF), the picture and sound are usually of higher quality than if they were received off-air. If you want to record off-air certain television programs, you should get a monitor/receiver. This instrument can act as a monitor (playing straight video and audio that has not been broadcast) or as a regular television set that can be tuned to a broadcast channel. The monitor/receiver usually has a variety of inputs and outputs on the back panel, besides a switch to designate the monitor or receiver mode (17.18). With an RF adapter (radio frequency adapter), you can play the signal from the small-format videotape recorder through an ordinary home television set. The output of the RF adapter is then connected to the VHF (very high frequency) antenna terminal of the set.

Lighting

Although the small-format camera performs remarkably well in all types of available lighting, you will not get professional pictures without sufficient baselight. Three small quartz instruments (with 600-1,000-watt lamps, focus adjustment mechanism, and barn doors), three lightweight collapsible stands, and an adequate AC extension cord will suffice for most additional lighting jobs. As pointed out in Sections 5 and 6, backlighting the scene is one of the most important additional lighting effects.

17.18 TV Monitor/Receiver.

Of all the wide array of available equipment, which one should you use? This is a question you should not answer until you know exactly what type of production you want to do.

Again, you should define the video functions, as mentioned in the beginning of this section, as carefully as possible. If you are going to use video mostly for looking at, such as observing children in a classroom, then you probably can get by with a simple camera mounted on a tripod, a simple cassette recorder, and a monitor. But if you are going to be mostly looking into or even creating events, then you will need more sophisticated equipment. If you do much in-the-field recording, you are probably better off with a portapak system than with a larger camera-recorder unit.

But if you do video experimentation in your studio, then you may want some more flexible, or better quality, camera and recorder units.

Operation The basic production techniques for small-format video are not much different from those employed for large studio-type equipment. Basic camera handling for proper visualization, the lighting principles, audio pickup techniques, picturization principles-are all the same. However, the portability of the equipment and its relative ease of operation might seduce you into using techniques that are not becoming either to the program or the equipment. We will, therefore, stress only those that are rather special to the small-format equipment. The area of concern is mostly in camera handling.

Here are some points you should keep in mind when operating a small-format camera:

1. Before using the camera, make sure that you have enough cable for your action radius. If you use a portapak with battery power, check the battery and all the connections from videotape recorder to camera. Make sure that the switch on the recorder unit is on "camera" and not on "TV."

2. Do a short test recording to see whether the whole system operates properly.

3. When playing back the test recording, put the switch to "TV." Don't forget to return the switch to the "camera" position before the actual recording.

4. If you use the recorder unit on a backpack, it is more comfortable to carry around; but you can't operate it while running the camera. You will find that the unit is easier to handle when it is hanging from your shoulder than when it is tucked away behind your back. Preferably you will have a two-person team. One of you can then run the camera, the other the videotape deck and the audio.

5. Although the vidicon tube can tolerate a great amount of light, never point the camera directly into a light source, and never, really never, into the sun, or into popping flash units from still cameras. Your tube will simply burn out.

6. Since the mechanism that holds the camera pickup tube is rather delicate, don't point the camera straight down. You will damage the camera. If you need a straight-down shot, use a mirror.

7. As with the big cameras, it is a good idea to let the camera warm up a little before using it.

8. Once it is warm, treat the camera very gently. Lay it down gently; don't just drop it on the table or the floor. Get a firm grip on it when you start shooting.

Remember that the tripod is still one of the most useful camera supports available.

9. Don't move the camera around widely without a reason. Let the objects in front do most of the moving.

There is nothing more revealing of a novice operator than excessive camera movement. Some amateurs move the camera about as though they were using a fire-hose on a burning building.

10. If you walk with your camera, hold it tightly so that it becomes an extension of yourself. Walk smoothly. Have your zoom lens in the extreme wide-angle position, or use a wide-angle lens.

11. Unless your camera is supported on a tripod, try to avoid much zooming-in any case, zooming in to tight CU's. If you have to zoom, zoom out. That way, you will end up in a wide-angle lens position, which minimizes the camera wiggles.5 S For more information on the operation of small-format cameras, see Robinson, The Video Primer.

12. Keep looking through your viewfinder. Everything the camera sees is there.

13. Avoid shooting objects against the lights or a light window. The objects will inevitably turn into silhouettes.

14. Don't forget to check your videotape from time to time. Make a reel change before you run out of tape; this way you won't lose the material close to the end of the tape.

15. The closer the microphone is to the sound source, the better your sound will be. Most remote operations permit the microphone to be in the picture. If you have to keep it out of the picture, you need a good directional mike. Remember that the built-in mike on the portapak unit is for general background sounds only.

It will not do a good job for specific sound pickups.

16. If you use a mixer, you can use several microphones. If the sound does not have to be synchronous with the action, you can record it separately and then dub it onto the videotape in postproduction.

17. Look at the lighting. When shooting indoors, you most likely need additional light. When shooting in color, see whether the lighting is excessively warm (way below 3,200 K) or cool (way above 3,200 K). If so, use the appropriate color temperature filter on your camera (if your camera happens to have such a device). Again, avoid shooting into the sun.

18. If you intend to edit the program in postproduction, get enough cutaways so that your work will be simplified later on.

19. Double-check the threading of the videotape. An improperly threaded tape can do great harm to the recorder as well as to the tape.

20. Keep all equipment clean, and please treat it gently. Because of the need to keep things small, a large amount of electronic components are wedged into a small space, making the small-format equipment quite a bit more vulnerable to shock than its large-format counterpart.

Finally, here are a few production hints. (1) Even if you don't intend to use the videotaped program on the air, get the proper releases from the people in your show, especially if it is a nonpublic event (someone at his home or in her office, for example). (2) Label your videotapes immediately after each recording. Indicate the machine on which the program was recorded, the subject and running time of the program, and the date of the recording. And (3) try to say something with each program you produce. There is enough visual pollution surrounding us as it is. If you want to communicate your experiences, clarify and intensify them so that they help us become more aware of ourselves and the world we live in than we would ordinarily be.

Summary

Video, in contrast to broadcast television, refers to the use of small-format equipment by individuals or small groups. Video is providing an alternative to the programming of broadcasting stations. Like any other form of television production, it can perform three principal functions: (1) to look at, (2) to look into, and (3) to create. Looking at means to observe an event as objectively as possible, the television equipment being used principally as a recording device. Looking into means to scrutinize an event from an extremely close point of view, the television equipment being used to intensify the event. Creating means to generate an event that exists nowhere in this particular form except on the television screen.

Small-format equipment includes (1) the small-format camera, (2) the portapak, (3) audio equipment, (4) small-format videotape recorders, (5) playback monitors, and (6) lighting.

Small-format cameras can be monochrome or color, and can be carried and operated easily by one person. The portapak consists of a small camera and a small-format videotape recorder, both of which one person can manage. The audio equipment ranges in size and sophistication from a microphone built into the camera to normal low-impedance microphones and mixers.

Small-format videotape recorders include (1) reel-to-reel machines, using tape ranging from 1/4 inch to 1 inch in width, and (2) video cassettes (self-contained tape cassettes), most commonly using 3/4-inch videotape. Many 1/2-inch videotape recorders, as well as many video cassettes, conform to the EIAJ (Electronic Industries Association of Japan) standard, which permits interchangeability of tapes that are recorded and played back on different machines.

The monitors used for playback are fed either directly by the camera or by the videotape recorder. An RF (radio frequency) signal can be reproduced by an ordinary television set. Most video operations use a monitor/receiver combination that can reproduce either direct video or an RF signal.

Most small-format equipment is built so that it can operate under normal lighting conditions.

However, additional lighting will help to produce higher quality pictures.

In respect to the actual operation of this highly mobile equipment, as well as the aesthetic production principles, video production is not drastically different from that of normal television.