|

|

.[Adapted from article in Harvey Rosenberg’s 1984 booklet, Understanding Tube Electronics, from New York Audio Labs]

To better understand the renaissance of tube technology, one must understand the progress of the audio industry over the last 30 years [as of 1984]. A significant date is 1956 when RCA introduced the transistor and ushered in the Japanese invasion of the audio industry. Has there been a remarkable improvement in sound quality since 1956?

And what are the benefits of all the billions of dollars spent on RD since 1956? On one level, we can be sure that almost everyone in America has a sound system, but it is also true that for the masses there has been little improvement in the quality of their musical lives. When you listen to Fisher, Marantz, and McIntosh equipment manufactured in American in the 1960’s and compare it to the latest Japanese electronics, it appears that the Japanese audio industry has not yet surpassed American design talent of that period. Before I can elucidate this subject, I will explain an important structure of obfuscation.

The standard practices in the audio industry of describing the quality of a component is a series of measurements, which is an attempt to convince you that components with better measurements are “better” than components with worse measurements. QED, an amplifier with 5% distortion cannot sound as good as an amplifier with 1% distortion. This would seem obvious except measurement standards in the audio industry are designed to obfuscate rather than elucidate. In fact, the industry has developed a series of measurement standards that are guaranteed to impress the consumer but have absolutely no bearing on describing the quality of the sound inherent in the circuit. What is fascinating about the “numbers game” is that it has backfired. Have you noticed the condition of the audio industry? Very dismal. Not much sex appeal left. The consumer knows that there are better ways to spend money: video recorder, home computer, hot tubs, because it is obvious that audio technology has not advanced (even though the numbers keep getting better) so that buying a new sound system will not give you a new and higher level of musical pleasure. In fact, the only thing you will probably get is a new face plate.

The sophisticated music lover sooner or later leaves the mass of buyers who are content with Japanese transistor equipment and begins to buy some of the transistor equipment designed in America, which is superior in every way to the “stuff’ coming from the Orient. This consumer has learned that the numbers game is nonsense and, in fact, that the equipment that sounds the worst usually has the best specifications. If this consumer develops sufficient sensitivity, and if music is a significant force in his life he will then, because of his need for refinement, move to tube electronics— the ultimate technology for music reproduction.

THE ULTIMATE TEST INSTRUMENT

What does our hearing mechanism, which was perfected over millions of years, have to do with audio measurement? It seems obvious to me: hearing is a Gestalt experience. This means it involves our entire being and is not just an experience that can be measured as an isolated phenomenon of the ear or brain. We hear with our entire body. All profound aesthetic experiences are total body experiences and nature intended it that way.

When we listen to music we listen with our entire beings and our entire body is making billions of judgments because billions of nerves are involved. When we listen to audio equipment, our ability to judge its “goodness” is quite easy because the most sophisticated test equipment in the world—you—(equipment that took millions of years to develop)—is making the measurements. Trust yourself.

Have you ever tuned a violin? How is it possible for a violinist to play an enormously complex musical score at breathtaking speed and make it appear easy? The answer is quite simple: Inherent in our nervous system is the neurological/musical bond that permits the brain to make the most subtle judgments and ultra high speed reaction to those judgments that makes all super computers seem primitive. There is no mega-computer or electro/mechanical system that can begin to approximate the skills of an accomplished musician. Furthermore, there is no piece of test equipment that can evaluate music or evaluate the musical performance of audio equipment better than you!

This is why tube electronics continues to survive. For the sensitive ear only tube electronics has the capacity to realize the natural harmonics of live music.

TESTING AUDIO EQUIPMENT

How then does the designer of audio equipment know the relationship between his engineering efforts and the ultimate quality of his work? The reality is that one must subject a new design to rigorous testing. Yet, ultimately, the designing of audio equipment is an art form where the designers ears must make the most important decisions.

With an appropriate music system this is quite easy and shouldn’t be thought of as an exclusive skill attainable by only golden-eared music lovers. It is quite easy for anyone when presented with choices to distinguish between “good” and “bad” musical quality.

In examining some of the reviews of New York Audio Laboratories products you might be impressed by their technical and electrical capabilities—a source of great pride, but let me assure you it was the most emotional listening experiences that ultimately determined the final direction of our engineering. Engineering is the tool of aesthetics. We are constantly amazed at significant yet subtle differences we can create in circuits that cannot be measured. As we have faith in our own musical instinct this is not a concern to us. Yet isn’t it strange that those companies that produce the most atrocious sounding equipment try to impress you the most with low steady state distortion figures?

Rest assured that tube electronics will never measure as well as transistor equipment because the traditional measurement used for indicating the performance of audio equipment glamorizes the junk equipment the most. When you compare some ancient tube equipment to some of the most modern transistor equipment you will completely understand the point. It is not that the numbers lie—they just never tell the whole truth.

TUBES vs TRANSISTORS vs PICKLES

The type of technology—the type of audio circuitry and the brand of equipment you use is unimportant in a very fundamental sense. The only thing that is important is that you are being musically nourished in your homes. It really doesn’t matter that the violinist is playing a Stradivarius violin—what does matter is the passion of the performance. After all, your audio equipment and the violin are only tools to serve the music.

There is much heated debate in the world of audio about the relative merits of tubes vs transistors and we shall address that question in short order, but let me preface the pedagogic content of this book by stating emphatically that if it were proven to us that a Dill pickle were the best device for creating the most vivid musical reality in your home, we would immediately embark on a research project to develop the musical potential of that seaweed-colored, flacid, sour object. It would be an aesthetic necessity for us to discover the potential of the Dill pickle—in spite of its burdensome cost or circuit complexity—because any avenue that would lead to a higher form of musical realism must be explored. The only question the circuit designer must ask himself—if he is serious about music—is what is the best circuitry to create the illusion of music in the home? This question should not in its initial stage of phrasing be concerned with cost, complexity or concern for difficulty. The technology is not the important thing—what is important is the pounding of your heart.

Now that I have made that clear, let me change position about audio technology and state that there is a great peculiarity in the audio industry. It is the only industry that is still developing tube circuitry and it is the only industry where the “state of the heart” equipment is tube circuitry. True enough that these ancient gizmos that glow in the dark are inappropriate in any other field but the only reason they are flourishing in the audio industry is that in audio circuitry they are superior to transistors. The only reason that N.Y.A.L. is devoted to tube circuitry is because they bring you closer to the illusion of live music. Again, if Dill pickles did a better job than tubes, we would write a book entitled “Understanding Pickle Electronics”. Until something better than tubes comes along, we shall continue our work with these lovable gizmos that glow in the dark.

PONDERING THE POTENTIAL

I have often been asked, “Should I buy tube circuitry?” I answer that question with “Why should you buy transistor circuitry?” Transistor circuitry, you see, has only one advantage: it is cost effective in the short run. In every other way they are not suitable for state of the art audio equipment, and this is easily proven with a simple metaphoric calculation. Ponder this for a moment: if anything is well suited to its purpose, it should be quite easy to get it to perform its designated function. Do the following calculation: try to add up all the money and man hours that have

You will notice that when you compare a reasonably sophisticated tube product to a transistor product that the transistor product seems to have a great deal more parts. This brings us to some very important circuit characteristics.

1. TUBE CIRCUITS (AUDIO) ARE VERY SIMPLE—As tubes are ideal audio amplification devices they do not require many circuit components or active devices to get them to do their job. As we all know, the simpler a circuit is the better it will sound. As the audio signal is quite frail in its natural form any degradation is immediately experienced. The rule in audio design is that every time a signal passes through a passive or active device, it is degraded somewhat (which explains why passive component quality must be very high). The inherent simplicity of tube circuits means that the signal is being degraded less; hence a clearer, wider, more lucid sound quality.

2. TUBES ARE LINEAR DEVICES—This means that there is a linear relation ship between voltage in and voltage out. This means that the gain is constant all along the frequency spectrum of the device. Transistors are at great liability in that they are inherently non-linear devices and when they are used in audio circuit they must be “compensated” to act in the linear way. This requires circuits which alter the inherent operating principal of the transistor. This adjustment of the signal which is very frail indeed alters it. I imagine this process as taking a beautiful piece of natural cotton fabric and processing it so that it is made into polyester that resembles the original cotton—fortunately, we can detect quite quickly the artificial nature of the product. So it is with transistors. The flat, compressed, two dimensional character of transistor electronics is directly related to their need to be “compensated” to act in a linear manner.

3. TUBES SOFT CLIP—First you must accept that all audio circuits clip under real world circumstances. Every phono cartridge under certain conditions overloads the front end of any preamp (even if it is mistracking) and every amplifier (in a moment of impassioned enthusiasm when. the volume is turned up) clips. When a transistor circuit clips it produces a great deal of odd order harmonics and this is called “hard clipping”. This type of clipping is inherent in the device. Tubes on the other hand produce even order harmonics when they clip and this is called “soft clipping”. Nothing you can do can make a transistor circuit “soft clip” (even though some manufacturers would like you to believe that they have developed a “soft clip ping” circuit; this is another attempt to get you to believe that you can get a transistor to act like a tube). Remember—a rose is a rose.

I know you are aware of listening fatigue. The root of listening fatigue is your great sensitivity to odd order harmonics—even those at extremely low levels. This type of harmonics causes listening fatigue. Do you know the sound of someone scratching glass with a metal scribe? That is the classic case of odd order harmonics. Do you remember what that did to your head and body? When music lovers say that tube electronics are less fatiguing, they are intuitively pointing to the fact that under real world circumstances tube electronics are less fatiguing, because they pro duce less odd order harmonics during clipping. This quite neatly segways into the most significant consideration which is the fact that tubes are capable of producing natural-musical harmonics and transistors (no matter what you do to them) simply can‘t.

To understand that most significant difference between tube and transistor circuits we must first look at the art of making musical instruments and before we do that, I must introduce you to two definitions—Harmonics and Timbre

HARMONICS, in acoustical terminology, are the individual component tones that together make up the overall musical tone the listener hears. Virtually all musical tones—indeed, all sounds—are composite; the string or air column or other sonorous body vibrates not only as a whole, giving rise to a fundamental tone, but also in halves, thirds, and progressively smaller segments, each of which produces proportionately higher pitches. These fractional vibrations lack the amplitude of the fundamental vibration, and thus their sounds generally are overpowered by the fundamental tone. Yet they are important because their relative strengths (governed by the peculiarities of each instrument) do much to determine the “color” or timbre of the composite tone—helping, for instance, to make the difference in sound between a flute and a trumpet playing the same note.

Harmonics fall into a natural series governed by the ratios of the vibrating segments. The 1st harmonic represents the fundamental tone resulting from the vibration of the whole; the 2nd harmonic is the octave (above the fundamental) produced by the two vibrating halves; the 3rd harmonic is a fifth higher still, engendered by the vibrating third; and so on:

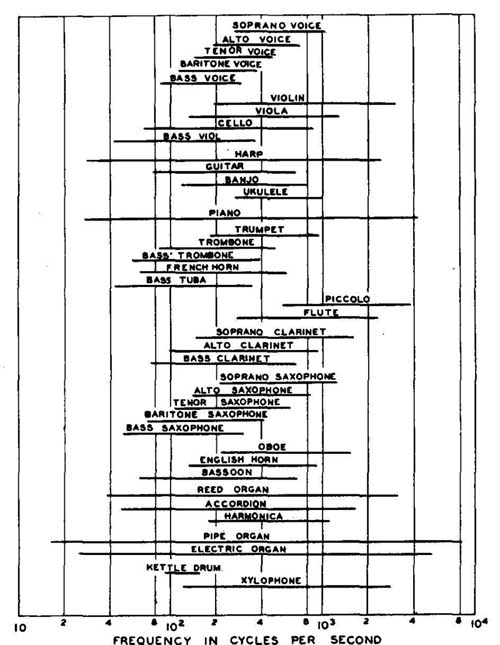

Figure 1. Frequency ranges of the fundamental frequencies of voices and

various musical instruments. (After Olson, Acoustical Engineering, D. Van

Nostrand Company, Inc., Princeton, 1957.)

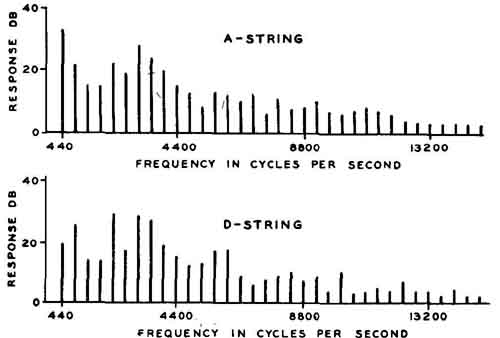

TIMBRE, is the most important fundamental attribute of all music. Timbre is that characteristic of a tone which depends on its harmonic structure (the proportion of even and odd order harmonics). The timbre of a tone is expressed in the number, intensity, distribution, and phase relations of its harmonics. Timbre, then, may be said to be the instantaneous cross section of the tone quality. For practical considerations, timbre is the harmonic spectrum. It ranges from a pure tone through an infinite number of changes in complexity up to a pitchless sound such as thermal noise. Timbre may be described as the characteristic which enables one to judge that two tones with the same pitch and loudness are dissimilar. For example, the frequency spectrums of the tones produced by the A string and the D string of a violin both sounding the fundamental tone A or 440 cycles are shown in Fig. 1. These two tones, emanating from the same instrument, have the same pitch and loudness and still appear to the listener to be two entirely different sounds. The reason for this fact is explained by the difference in the harmonic spectrums of the two tones. Referring to Fig. 2, it will be seen that the complexion of the harmonic spectrums of the two tones is entirely different. This accounts of the fact that these two tones appear to be entirely different to the listener.

Timbre may be said to be the characteristic which enables the listener to recognize the kind of musical instrument which produces the tone. The following chart gives the tone structure of typical musical instruments. An examination of these spectrums shows that the essential difference between the musical instruments resides in the harmonic structure. It is in terms of timbre that we differentiate the tonal character of musical instruments, or voices.

---Music, Physics and Engineering, Harry F. Olson

Figure 2. The acoustic spectrums of the A and D strings of a violin for

the tone 440 cycles.

What we know for sure is that it takes some form of vibration from some instrument to make music. It is the instrument maker’s job to make things vibrate “naturally”. That is why they study harmonics. The art of creating a musical instrument is the art of making instruments that have musically natural harmonics which is the juggling of materials until the proportion of even and odd order harmonics are just right so that we can reach the conclusion that the tone, (determined by the timbre) is “natural.” If we alter the harmonics of the tone we will alter the timbre, making the instrument sound unnatural. The instrument maker’s art is knowing how to balance even and odd order harmonics.

It is no accident that fundamental to the operation of the tube it produces harmonics that are naturally sympathetic to the harmonics of music. This electrical fact is at the heart of why tube electronics have endured. Let us probe deeper into this phenomenon. When you design transistor equipment you can, by using enough feed back, produce a circuit which has vanishing low levels of total harmonic distortion (THD) which is exactly those circuits which sound worst. Our ear is more sensitive to the balance of even and odd order harmonics than to total harmonic distortion. It is obvious that a device that has a .05 distortion level and produces the proper balance of even and odd order harmonics will sound more musical than the device that has .0000000001 distortion and has the harmonics wrong. Think about this very simple idea—would you like to listen to a very clean sounding signal where the violin sounds out of pitch or has an unnatural timbre, or would you like to listen to some signal that has an insignificantly higher level of distortion and all the instruments sound like they have natural pitch and timbre?

It is obvious to us that the universal “error” of conventional transistor electronics is that they are altering the timbre of all the instruments and voices. The nasal constricted sound that is so typical of medium priced electronics and the very antiseptic yet unnatural sound of all expensive solid state electronics is directly related to the fact that they (by their nature) are adding a higher proportion of odd order harmonics than was in the original signal. By doing this they are altering the natural harmonic balance of the music. This sounds unnatural to our ears for the very obvious reason that they have altered the timbre of the instruments. There is nothing you can do to a transistor to prevent this from occurring. This is the technological and aesthetic wall that all designers of audio equipment must face. No matter how sophisticated or refined, transistor circuits will never be able to accurately reproduce musical harmonics. Their nature is not suited to this task. They are superb switches and regulators, and have revolutionized modern life, but in audio circuits they are at an impossible disadvantage relative to tubes.

If you return to an earlier thought I was ruminating on—the progress of audio industry in the last 30 years, you will now appreciate why there has been so little progress. Can you imagine the musical instrument business trying to create plastic violins, claiming that they sound just like real wood ones? You will never get plastic to sound like wood—no matter how hard you work at it—no matter how many billions of dollars you spend on research and development—because as Gertrude Stein once said—A Rose is A Rose.

If you are seeking the level of illusion that we described earlier, you will never be successful if you don’t start out with electronics that are sympathetic to real music. You can’t fool your hearing. You can’t alter your sensitivities that have been living in your genes for millions of years. Stop trying to fool yourself, and accept what instrument makers learned hundreds of years ago—for music to sound natural there must be the proper balance between even and odd order harmonics.

IN SUMMARY

The reason that tubes are superior audio devices is that inherent in their electrical nature they produce a higher proportion of even than odd order harmonics. This proportionality resembles most closely the natural harmonics of music therefore a signal passing through a tube is altered in a way that is sympathetic to the nature of the signal, in that it does not distort the relationship between even and odd order harmonics . . . Transistors on the other hand produce a larger proportion of odd order harmonics which is dissimilar to the harmonics that appear naturally in music. A signal when passing through a transistor will have the proportions of odd and even order harmonics altered in such a way that they will no longer sound in natural balance. In effect the altering of the natural harmonic balance of the signal is altering the timbre of the music. This explains the great difference in the “quality” of sound between tubes and transistor circuits.

VACUUM TUBES

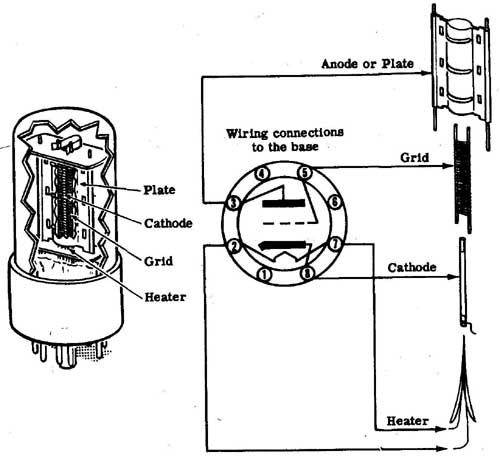

The simplest audio vacuum tube consists of three parts enclosed in a glass bulb from which as much air as possible has been pumped. The first and inside part is the “filament”. It consists of one or more wires which are heated to incandescence by current passing through them. The second part, consisting of a spiral spring or a very open-mesh screenlike part, is called the “grid.” The third part, called the “plate,” surrounds the grid. It is usually made of sheet metal, but fine-mesh screen is used in some of the smaller tubes. The base of the tube has four prongs. The two larger ones are connected to the filament. The grid and plate are each connected to one of the two smaller prongs.

The screen-grid tube has an extra grid which surrounds the plate, both inside and out. The pentode, brought out in 1930, has still another grid sometimes connected to the mid-point of the filament or to the cathode internally and sometimes connected to a separate pin on the base. Many tubes have an insulated metal tube, called the “cathode,” surround the filament, which is heated by the filament and gives off electrons instead of the filament. When a cathode is used, the filament is called a “heater.’’

OPERATION OF A VACUUM TUBE

When the proper voltage is applied across the filament terminals of a tube, the filament becomes incandescent. This condition of the filament allows large numbers of electrons to escape and surround the filament like a cloud. A source of high voltage is connected between the plate and filament with the positive potential connected to the plate. The positive charge thus placed on the plate attracts the electrons surrounding the filament, and they move toward the plate. The grid is directly across the path of these electrons. In most circuits, the grid is maintained at a negative potential in respect to the filament or cathode. It, therefore, has the same charge as the electrons and repels them, forcing them back toward the filament and thus reducing the number that reach the plate. Increasing the negative charge, or “grid bias,” as it is called, would increase the force of repulsion and further reduce the number of electrons reaching the plate. Conversely, as the negative grid bias is reduced to zero, the plate current increases. If the grid is made positive in respect to the cathode, it will attract electrons from the cathode; however, most of them are captured by the higher positive charge on the plate. In effect, a positive grid gives the electrons a good start on their way to the plate, at the same time retaining a few itself.

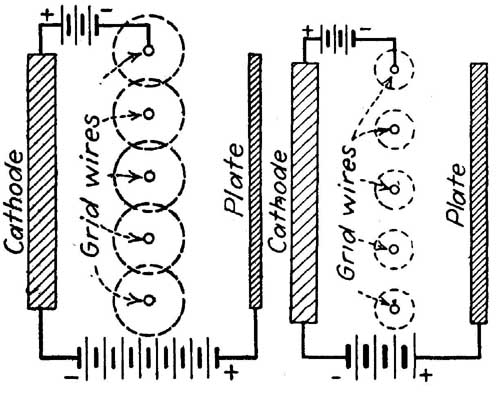

The operation of the grid is illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4. In these figures, the extent of the electrostatic field about the grid wires is indicated by the dotted circles. In Fig. 3, the grid voltage is a low negative value. This will produce a small field about the wires leaving large gaps having little if any field strength. The electrons pass easily through these gaps to the plate. In Fig. 4, the grid voltage has been increased to such an extent that the electrostatic fields surrounding the grid wires overlap and form a continuous negative field which repels all electrons trying to get to the plate. Thus, as the grid voltage is changed, the strength of the electrostatic field about it is changed, and this in turn controls the number of electrons that can reach the plate.

(left) Fig. 3. Diagram illustrating the operation of a vacuum tube with low grid

bias. (right) Fig. 4. Diagram illustrating the operation of a vacuum tube

with high grid bias.

The PLATE of the tube is charged to a high voltage provided by the B+ supply.

That high positive charge attracts the negatively charged electrons boiled

from the cathode. If no obstacle were placed between the cathode and plate,

all the electrons released by the cathode would flow to this point, producing

a current flow limited only by the power supply capacity and the characteristics

of the tube.

The GRID of the tube is that “obstacle”. The grid is usually charged to a slight negative potential, with respect to the cathode. If the grid is more negative than the cathode, it tends to inhibit the flow of electrons from cathode to plate. In addition to that slight “bias” on the grid, the signal appears. Since the signal is AC (alternating cur rent), it tends to make the grid potential vary; it becomes alternatively more and less negative than the bias established by circuit design. As the grid voltage varies (due to the signal impressed on it), the flow of current from cathode to plate increases and decreases—as an amplified copy of the original signal. The grid, then, acts very much as a valve in a water pipe, controlling the flow from an area of high pressure to one where it is lower. It doesn’t take much to turn the valve, just as it doesn’t take much signal voltage to control the total current flow of the tube.

The CATHODE is the source of the electrons attracted to the plate and controlled by the grid. The cathode is coated with a substance which, when heated, emits electrons in profusion. Because the cathode is connected to “ground”, the supply of electrons is constantly replenished.

The FILAMENT, or “heater”, is connected to a power supply of its own which provides sufficient energy to heat the filament to incandescence. That heat is transferred to the cathode, which is thereby stimulated to emit electrons. In a few tubes, the filament itself acts as the cathode.

== ==

ALSO SEE:

== == ==