AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

Overview

Managers and users of process control systems are quite often faced with a situation where a decision is required on matters involving large sums of money. In today's economy, the game is survival of the fittest, and the game has a set of rules that is played on the global scene (some say there are no rules). If you lose, you're out. Markets that were guaranteed few decades ago are now threatened by international competition.

Product life cycles are much shorter, and technology is changing at an unwavering rate. In addition, production needs to be faster, less expensive on a per unit basis, and of high quality.

AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

The olden days, when products had a long life cycle, the domestic market was secure, and the economical conditions could be predicted, are all gone. We are in a new world, a world of international competition, where survival is a daily issue and vital decisions are frequently required.

A mismatch of process, production capabilities, and customer requirements generally results in poor quality, high cost, and low morale. On the other hand, success not only means survival but also increased markets and increased profits. From a process control point of view, one of the main tools in achieving success is the proper implementation of modern process control systems (see Section 9 for further details). These systems are, when well applied, an aid to cost effective, reliable, high-quality, pollution-reducing, and flexible production (i.e., an aid to survival).

In existing plants, the implementation of modern control systems consists of replacing existing obsolete controls. The replacement must be done with the minimum of interruption to plant production and with the knowledge that the investment is worth taking.

When decisions are made, they must be the correct ones. The techniques learned in this Section should help the decision-making process by justifying certain major modifications. Some basic tools commonly used in the decision-making process are:

• auditing,

• evaluation of plant needs,

• justification, and

• system evaluation.

In many plants, the auditing of industrial control systems is becoming a requirement to ensure proper operation and the maintenance of corporate assets. In today's economy, control systems are becoming more and more vital to plant operation, and therefore, their functionality must be ensured. The failure of control systems could be a sizeable financial loss, and, even more dangerously, it could be hazardous to life and to the environment. On the other hand, their efficient functionality will provide safety and quality products and will handle fast, complex, and hazardous processes. Auditing may be defined as a form of quality assurance for the control sys tem to evaluate its intended functionality.

The evaluation of plant needs is an activity that identifies the needs of the plant. These needs, once identified, typically become the basis of the control system specification. This is a pro-cess in which decisions regarding the plant needs must be made. These decisions must consider the available choices and should be based on facts, not on the opinion of the person (or persons) with the loudest voice or the highest authority. Evaluation of plant needs is generally done following an audit or sometimes instead of an audit.

Justification assesses the need to invest, helps establish the objectives, and identifies the profit ability of the investment. Without it, the investment could be unprofitable, or the system selected may not meet the intended application. In many cases, the funds required for large investments in process control systems need to be borrowed, while at the same time, management has many other needs for funds in the plant. The decision on where to invest funds and which improvement project or expansion is to be chosen depends on the return on that investment and the amount of risk involved. In general, this is a difficult decision that must be substantiated, thus the need for justification.

System evaluation is a tool commonly used to evaluate bids following the submittals from different vendors, and a decision must be made concerning which one most closely meets the plant needs. This is done through a quantified system evaluation.

These four decision tools are actually interrelated and are often used together (see FIG. 1).

======

FIG. 1 Relationship between different decision tools.

1. AUDITING (to verify the status of the existing control system and decide what to do next)

2. EVALUATION OF PLANT NEEDS (to identify the needs of a plant and decide what is required)

3. JUSTIFICATION (to ensure that the money to be spent is worth it and that the investment will resolve the issues raised by the audit and the evaluation of plant needs)

4. SYSTEM EVALUATION (to decide which of the systems submitted by vendors is the best for the application; this decision is based on a quantified approach)

=======

Auditing

The auditing function is a systematic and independent activity that provides plant personnel with the status of the control systems and the condition of the technical data related to these systems. In other words, and according to ISO 9000, the purpose of an audit is to evaluate the need for improvement or corrective action. It also determines compliance with regulations and corporate standards. The result of the audit is provided in the form of an audit report.

Each company has its own auditing methods and standards, which vary from strict point-by point procedures to very loose personal judgments. The ISO 9000 International Standard, which is one of the references for this text, has basic auditing guidelines. They are, however, non-disciplinary and do not look at the specific needs of control technology. There are many types of audits; this Section will deal only with the auditing of industrial process control systems. Other forms of audits, such as environmental, safety, and accounting, are outside its scope and are specialties within their own disciplines.

Control personnel sooner or later may become involved in an audit, either as part of an auditing team or as part of the plant personnel being interviewed by an auditing team. If selected as an auditor, a control engineer needs to be experienced in the technology of industrial control systems and be aware of the regulations and standards. Sometimes the engineer will be familiar with the plant being audited; in other situations, that will not be the case.

Auditing the functionality of the existing control system determines whether the present sys tem meets the needs of the plant. The ISO 9000 International Standard recommends that "design requalification" be performed to ensure that the design is still valid with respect to all specified requirements.

To audit the functionality of control systems, the auditor must understand the needs of the different plant functions: management, engineering, customer requirements, legislation, operations, maintenance, and, in many cases, other support services, such as purchasing, stores, and receiving.

Two points to keep in mind:

1. The auditing of control systems must be an objective activity.

2. In an effort to take some of the burden from the shoulders of future auditors, it should be pointed out that not every detail, important or not, can be audited. Verification of existing technical data can be performed only on a random basis, and considering the amount of data available, it is expected that some important details will be missed. However, every effort should be attempted to minimize this.

The Auditing Function

This Section will provide the general guidelines for conducting an audit. Obviously, this text cannot cover all the details; the control engineer's knowledge and experience will play a key role in customizing an audit for a particular case, keeping in mind that no two audits are alike.

The audit function has, in addition to being a technical activity, a sometimes difficult aspect known as human emotions. An auditor interfaces extensively with plant personnel, who may sometimes consider this an intrusion, a person who will report to management their inabilities.

This human side of the audit should be handled tactfully, yet objectively. For the well-pre pared, experienced control engineer, with good interpersonal skills, it is feasible to conduct a control system audit the first time one is selected for this activity.

As a starting point, plant management should inform relevant plant personnel about the upcoming audit, cooperate with the auditor, and provide the required resources.

Scope of Work and Time Required

Audits by nature are disruptive to the workplace; they take the time of key personnel, who quite often wonder about the purpose of the activity. As far as they are concerned, everything is operating OK, considering the working conditions, which won't be changed anyway.

To minimize the disruption, the auditor should perform the audit quickly and efficiently. To assess the scope of work, some careful planning is necessary. In most cases, especially for plants being audited for the first time, lengthy pre-auditing activities are required.

Plants that are audited for the first time or plants that need many improvements will obviously require more auditing time than other plants. A typical medium-sized plant with an average amount of control systems would need, as a rule, about 10 man-days of on-site auditing activities (note that these on-site auditing activities do not include pre-auditing and post-auditing activities). On the other hand, a small plant would take about 5 man-days, and a large plant, about 20 to 30 man-days.

In the case of a medium-sized plant, the total man-days for auditing the plant could more or less be distributed as follows:

A. Pre-auditing activities may require about 5 man-days of an auditor's time to prepare an audit protocol and review.

• plant P&IDs,

• job descriptions of control personnel,

• previous audit reports,

• plant layouts,

• operating procedures,

• administrative practices,

• regulatory requirements in effect at the site, and

• plant standards.

B. On-site auditing may require about 10 man-days of an auditor's time to conclude.

• initial meeting with management and key personnel, explaining the upcoming audit activities (half a day),

• plant visit and review of existing plant technical data (2 days), interviews (2 days),

• actual auditing and verification of interview findings (3 days or more),

• preparation of preliminary audit report (1.5 days), and

• discussion of preliminary audit report with management (1 day).

Further discussion on some of these activities will be presented later on in this chap ter.

C. Post-auditing activities may require about 3 man-days of an auditor's time to

• clean up and file all audit data (for future reference) (1.5 days), and

• prepare and send final audit report (1.5 days).

Protocol

The auditing activities are guided by the audit protocol. This document, prepared prior to the start of an audit, helps the auditor plan and conduct the auditing activities and can be defined as the auditor's road map or audit plan. It is generally in the form of a questionnaire that serves as a continuous reminder of what needs to be done in step-by-step form. Without it, the auditor may forget what to ask, waste time, duplicate questions, and eventually end up with little significant data to report.

Pre-auditing activities, such as reviewing plant data before going to the plant are essential to fine tuning the protocol. The auditor will find that the core of the protocol tends to repeat from audit to audit, but the details must be customized for each audit. Generally, there is about a 50/ 50 split between core and details.

Auditors

The auditor is expected to be familiar with the regulations and plant standards in effect at the facility. In addition, he or she is expected to be well experienced in the field of process control systems and have the necessary degree of independence from the plant being audited.

Auditors of process control systems normally come from one of three sources:

1. From within the plant. This approach is the least recommended because it is quite difficult to self-audit or to audit a colleague's work. The ISO 9000 International Standards recommend that auditors should not have a direct responsibility in the areas being audited.

2. From another plant (or office) belonging to the same organization. This is a much better approach than the first because it satisfies two conditions: some familiarity with the plant and a relatively arms-length approach (i.e., reasonable independence).

3. From an outside firm specializing in the auditing of control systems. This approach allows the auditing function to be carried out with a minimum of interference to plant personnel and at the same time allows an objective, experienced, and fresh approach to the auditing process. In addition, an outsider can in many cases communicate better because plant personnel do not have to worry about personalities and internal politics.

The auditing function, depending on the size of the task and on the available time, could be performed either by a single auditor or by a group of auditors. In the latter case, the group requires a leader to select an auditing team, coordinate the activities, review the progress, avoid duplication of activities, prepare the draft audit report, and so on.

Interviews

A key part of the in-plant auditing process is one-on-one interviews between the auditors and key members of the plant's process control team. These interviews give the auditor a good understanding of the day-to-day performance, as well as a chance to collect information that would have been otherwise hard to identify by just looking at documents.

The results of these interviews will become part of the audit report, with the source of information always confidential and never revealed. The confidentiality of these interviews must be understood and accepted by management, the interviewer, and the interviewee.

Before starting an interview, the auditor needs to be prepared by becoming familiar with the interviewee's functions at the plant and by listing the important points for discussion with the interviewee. It is important to plan enough time for the interview because rushing this activity will present the wrong impression. It is important to schedule time, place, and approximate duration of the interview.

At the interview, the auditor needs to establish a good rapport with the interviewee by arriving on time; introducing himself or herself; being friendly and courteous (it is not always easy to open up to an auditor who is a stranger); explaining the purpose of the interview and the benefit of the audit to all personnel; and informing the interviewee that the source of all audit information will remain confidential.

As the interview starts, the auditor should:

• keep note taking to a minimum,

• distinguish between facts and personal opinions,

• look for specific examples,

• always be clear when asking questions (avoid the use of fancy technical terms or buzz words),

• ask one question at a time, and

• allow the interviewee enough time to answer the question and listen carefully.

A good interviewer will look at the other person, be genuinely interested in what is being said, and ask questions, keeping "why" last (start with who, what, where, when). The interviewer should not rush or cut the interviewee off and should keep on the subject until it has been completely covered.

The main purpose of the interview is to gather information; therefore, the auditor should, with the help of the audit protocol, be able to ask the necessary questions and understand the answers received. This is the reason the auditor must be an expert in the field of process control systems in addition to being a skilled interviewer.

Interviews can become difficult if shyness, nervousness, talkativeness, aggressiveness, lack of trust, and defensive attitudes are allowed. The auditor must avoid them.

As the interview draws to an end, the auditor should hold to the schedule, ask the interviewee if he or she has any questions, thank him or her for the time, and try to end on a positive note.

After the interview, the auditor should immediately summarize the discussion and write down the results. In some cases, the auditor may need to contact the interviewee once more for further clarification or for additional information.

Searching and Checking of Drawings and Documents

By now, the auditor has completed the interviews and has learned quite a bit about the plant- its problems, the way things are done, and what people like and dislike about the plant operation. The next step is a search-and-check mission.

The auditor starts by looking at documents and drawings to determine whether they are kept updated, and then tracks a number of items on the P&IDs to the instrument list, the loop diagrams, and the actual plant installation. Is it all there? Is it correct? This random check of detailed data should encompass other items, such as the control part of the operating instructions, computer systems, software documentation, and so on.

Such a search must be systematic, and shortcuts are not recommended. The auditor may be astonished at what can be discovered by taking the long route. It is generally quite informative, and it may lead to points never thought of or mentioned previously (intentionally or unintentionally).

The notes collected should be assembled and summarized at the end of each audit day. The audit process is not an 8 to 5 job. Long night hours are spent reviewing, finalizing, summarizing, and monitoring the progress. In the case of an audit team, the next day's activities must be coordinated and reviewed with the group, typically at dinner time.

Report

The audit report provides the significant findings of the audit to help the plant achieve compliance with regulations and plant requirements. However, the auditor should not forget the confidentiality factor. The report should include all of the good practices in use at the plant, all the exceptions, and all the strengths and weaknesses.

An additional item, recommendations, can be added in the report. Whether to include recommendations or not has been the subject of numerous debates. Some auditors claim that it is not their function to recommend solutions but only to pinpoint problems. This approach results from the question of the auditor's liability and the reasoning that plant personnel are more knowledgeable when it comes to solving problems in their own plant. On the other hand, some auditors take the approach that the auditor, with his or her vast experience, needs to suggest solutions, particularly if the auditor belongs to the same organization. In any case, the addition of recommendations to the report should be decided between plant management and the auditor when the scope of the audit is being defined. Generally, plant management asks for the addition of recommendations from the auditor.

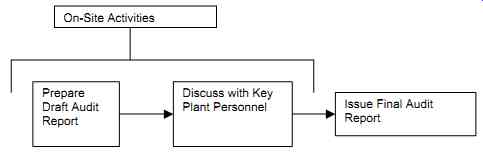

The audit report (see FIG. 2) goes through two stages. The first stage is the draft audit report, which is usually prepared on-site at the end of the auditing process. Its content must be discussed with the key plant personnel and, in most cases, the plant manager as well. The second stage is the final report, which is prepared within a month or so after the draft report. The final report, as a rule, does not include any new findings beyond the draft report. The final report is usually addressed to the plant manager, with copies to key plant personnel. It is recommended that this distribution list be agreed upon at the beginning of the audit.

FIG. 2 The steps for preparing an audit report.

In some cases, when recommendations are part of the report, a follow-up activity (perhaps 3 to 6 months later) may be needed to check the implementation of the recommendations.

A typical audit report consists of two main sections: an introduction and the findings (and recommendations if required).

The Introduction covers some basic elements, such as

• the purpose and scope of the audit,

• the purpose of the audit report,

• a list of the audit team and their affiliations, and

• a description of the facility being audited.

The Findings (and recommendations) cover

• a summary of the plant's actions following the previous audit,

• a list of good practices at the plant, and

• a list of non-conformances (followed by recommendations).

The audit report must be factual and avoid opinions and speculations. The report should avoid extreme language (e.g., incompetent and terrible), use familiar terminology (i.e., minimize buzz words), and avoid drawing legal opinions or judgments.

A typical audit report has been produced as an example.

History, Frequency, and Record of Audits

The frequency of control system audits varies, depending on many factors, but in general, it is between three to five years. The concept of control system auditing is relatively new; therefore, the history of such audits is in most cases limited at best to one or two.

The audit program, if it exists at a plant, is typically a scheduled activity that indicates the frequency and scope of control system auditing. Generally, it covers the auditing of many engineering disciplines, such as safety, mechanical, and civil, with the control systems being a part of the total picture. Without such a program, the need for audits tends to be forgotten or postponed until a costly hazardous event occurs, at which time somebody in management asks, "When was the last time we had an audit? Who is responsible for audits? Why were no audits performed?" The frequency of audits is a matter generally determined by plant management and depends on such factors as the importance of the control system in question, the results of previous audits, the overall condition of the plant engineering and maintenance functions, and regulatory requirements. Once the frequency of auditing is defined, the auditor needs to verify the time span between the last audit and the present one to confirm compliance (or non-compliance).

The records of the last audit and the verification that the recommendations were carried out should form part of any audit. In most audit interviews, the last audit report is reviewed and discussed, because it gives the auditor a good view of the strong and weak points at the plant and provides a reasonable starting point for further discussions. In most cases, the two key documents that will break the ice at interview time are the job descriptions and the last audit report.

Auditing of Management

The first step in auditing the control system support functions is to audit the management side of control systems. In most cases, the auditor will find this step to be one of the easiest and fastest to accomplish.

The auditor will typically cover in this activity:

1. The plant organization, which includes

• the structure of the organization,

• the definitions of authority and responsibility, and

• the job descriptions.

With this information, the auditor will first learn about the official lines of communication and responsibility and then about the different members of the control team at the plant -- their roles and their relationships to plant management.

2. The history and record of previous audits

3. The management of drawings and documents

4. Personnel training

Auditing of Engineering Records

The auditor will now begin the audit of the plant technical information, also known as the engineering records. This is where his or her experience as a process control engineer comes into play. The auditor will discover a great deal of available data. But is it complete and correct? He or she may find that the records have not been updated to reflect plant changes. The auditor's function is to find that out.

Engineering records contain essential technical data and are regularly used by plant personnel;

therefore, they require auditing. The engineering records that can be audited are described in Section 14 of this guide. Additional documents may be encountered, and it is up to the auditor to decide if they should be audited.

To conform to the ISO 9000 International Standard, the plant being audited must have in place a system for identification, collection, indexing, filing, storage, maintenance, retrieval, and disposition of pertinent engineering records.

Two points to consider:

First, the auditor must realize that it is impossible to sift through all the data. The audit will be a random check that relies heavily on the auditor's experience and gut feelings about where to search.

Second, the auditor must be ready for surprises. Data that should be accessible and up to date is often missing or unusable.

Auditing of Maintenance

The last part of auditing activities for control system support functions is not as straightforward as auditing management and engineering records because it comprises a large portion of human interrelations. But the auditor should not be discouraged; it can be accomplished successfully through a combination of technical know-how, persistence, patience, tact, and experience.

The auditor must verify that not only is the maintenance done correctly but also that any alterations comply with the electrical code in effect at the site. The auditor should keep in mind that modifications to approved equipment may void the approval of such equipment.

As the audit is conducted, considering the vastness of maintenance auditing, the auditor should periodically pick one item of his or her choice, concentrate on it, and follow it through. For example, when equipment is withdrawn from service, what do they do with the exposed wires? Are they correctly terminated in an appropriate enclosure? Are they insulated? Are they left hanging loose? The auditor may find it useful to check on-site some of the data acquired during the interviews (e.g., take the loop drawings and check some minor items, such as does the cable number on the drawing match the one on the actual cable). Another item that must be checked is how closely the vendor's instructions are followed when maintenance is performed.

A primary activity in maintenance is the calibration of equipment (see Section 17). Quite often, this is performed in a calibration shop, where most of the calibrating equipment is located. The auditor must evaluate the quality of the calibration shop, including the quality of the instruments used for calibration, their accuracy (obviously it must be better than the instruments being calibrated), and the calibration records for all the instruments. Verify that control equipment is calibrated prior to first use to confirm all settings (an ISO 9000 recommendation).

Where repair has been done on personnel safety-related equipment, the auditor should check to see if the plant policy is to have a second person inspect the work. If this is not the case, he or she must verify how safety and quality of the work are ensured. After all, anyone can make a mistake, but no one can afford deadly ones.

The auditor should observe carefully to note any conflicts that may exist between maintenance and their three main links-engineering, purchasing, and production. For example, Is purchasing responsive to maintenance needs? Is production satisfied with maintenance? Do they release equipment for preventive maintenance? During the auditing of the activities related to maintenance and testing in hazardous locations, the auditor will not be able, in most cases, to witness those activities. The information that must be collected will be based on interviews and on visually checking the equipment used in testing.

As the auditor conducts the audit interviews, he or she should ascertain the procedures used in maintaining equipment in hazardous environments. It is a good idea to pick one item of his or her choice and discuss it in detail. For example, how is the opening of an explosion-proof box performed? How is the absence of power ensured? Do they wait for stored electrical energy to dissipate before opening? Do they allow the equipment's surface temperature to come down first? What is done if maintenance is required but power cannot be cut off? Refer to Section 16 for further information on the topic of Maintenance.