by J.W.F. Puett

"Scott--The Stradivarius of Radio"--these were the only identifying words inscribed on the dial of the Scott Philharmonic, the world's finest radio receiver.

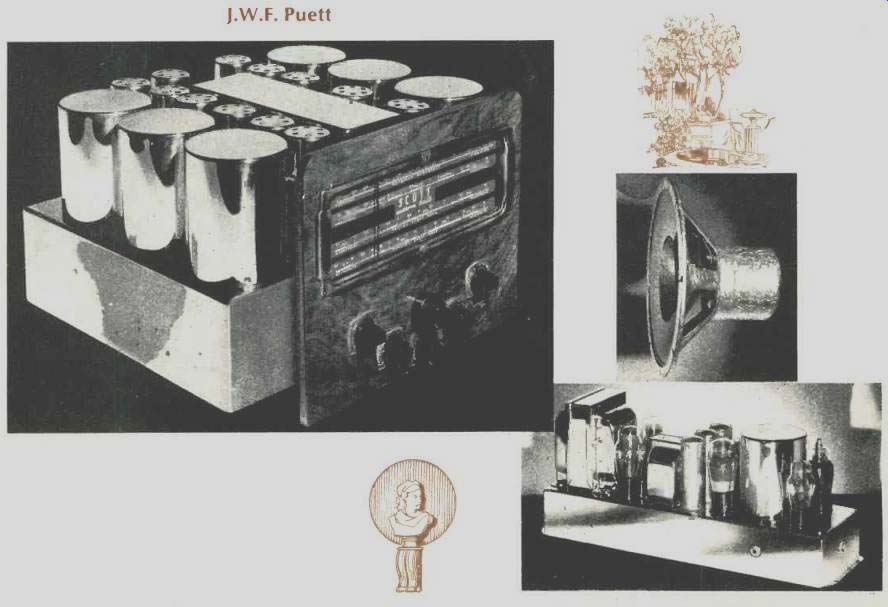

From 1924 to 1945, E.H. Scott custom built instruments for reproducing radio and recorded music. His customers represented the most discriminating radio market in existence--world famous musicians, critical laymen listeners, engineers, and distinguished scientists. Although nearly half a century old, many Scott receivers are still treasured by their original owners.

In 1933, Mr. Scott wrote, "Right from the start, my only interest and ambition has been to design and build the very finest radio receiver possible." For more than 10 years, he repeatedly challenged the whole world of radio to any kind of competitive tone or distance reception test, but not a single manufacturer was willing to accept the challenge.

Scott not only kept up with the state-of-the-art designs, he often surged far ahead of his time. He designed the first receiver to successfully use more than one r.f. amplifier stage.

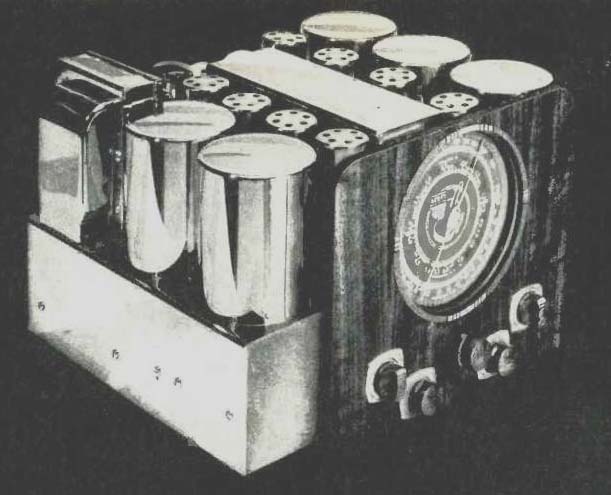

Scott manufactured the first receiver which successfully employed the screen-grid tube and later the first set which successfully utilized the "triple-grid super-control" type 57 and 58 tubes. He was first with a 500 to 15 meter all-wave set with band switching instead of plug-in coils. His receivers were first to provide 10-kHz selectivity at a field strength of 600 to 1. In the realm of high fidelity, a Scott receiver was the first with the capability of reproducing "the entire audio range" from 30 Hz to 16 kHz.

E.H. Scott was probably the first radio manufacturer to employ reliability testing. He designed and utilized electric rotators to test moving parts, electro-mechanical shaking tables to test the permanence of adjustable components, and a special refrigeration cabinet to simulate humid conditions in tropical climates. All Scott receivers were thoroughly tested, both mechanically and electrically before delivery to the customer.

The shielding in Scott radios was superb. At the "Century of Progress" (1933 Chicago World's Fair), a Scott Allwave Deluxe receiver was installed in the elevator control room at the top of the Observation Tower of the Sky Ride. Each day, eight to twelve thou sand people visited the control room.

They heard music and news coming from the radio without the slightest trace of electrical interference, yet the set was situated in the center of a mass of motors, dynamos, and control contactors. Very few receivers manufactured today could match that performance.

Reliable Reception

In 1935, Scott ads heralded the 23-tube Allwave Imperial. This set utilized four type 2A3 triode tubes in a class-A, push-pull-parallel audio amplifier rated at 35-watts.

Four of Chicago's largest theaters were slated to use receivers manufactured by two very well-known companies to pick up the Joe Louis vs. Max Baer fight which was only available from a distant station. The program material was to be connected from the receivers to the $20,000.00 theater sound system. It was found that neither of the receivers was capable of bringing a sufficiently clear signal into the theaters. The theater owner asked Mr. Scott if he thought his new Allwave Imperial might do the job.

Scott replied, "It is not only capable of bringing in the signal, but of delivering the volume required without using the theater sound systems!" The next day, an Allwave Imperial was installed in the Drake theater. To the owner's amazement, it brought in the desired station without even a crackle from the ambient downtown electrical noise and filled every corner of the theater with the volume turned only one-third up. With a standing-room-only audience, the volume was turned one-half up.

Each piece of lumber used for construction of a Scott console was first stacked in the open air where it was allowed to dry from one to three years, depending upon its thickness. Following the air drying, the wood was placed in a dry kiln and steamed from 24 to 36 hours to remove all acids. After steaming, it was left in the dry kiln at a temperature of 140 degrees from three to six weeks, depending upon the thickness and kind of lumber.

When the moisture content was reduced to between six and ten percent, the lumber was placed in a cooling shed for several days. It was then placed back in the kiln where dry heat was applied until the moisture content was further reduced to between four and six percent. The wood was finally given a secret-process treatment which made it practically impervious to moisture. Only then was it ready to be built into Scott consoles by men who had devoted their lives to building fine furniture.

(Source: Audio magazine, Feb. 1979)

Also see: Link | --My Friend the Maestro--fond reminiscences of Leopold Stokowski (Jan. 1978)

= = = =