by Gary Stock

To the student of contemporary American music, the name and works of Morton Gould need little introduction. He stands as one of the nation's foremost composers, not only be cause of his symphonic works, but also because of the eclectic body of popular music-pieces for film, ballet, Broadway, and television--which he has written.

From the first flush of national popularity acquired through his Depression-era radio broadcasts, Gould has explored an ever-widening array of musical forms. He developed the concept of the "little symphony" in his well-known symphoniettes, examined jazz forms in "Interplay," contributed to what might be called American patriotic music with "American Ballads," "Columbia," and "American Salute," and composed bal let scores for artists like de Mille ("Fall River Legend"), Balanchine ("Clarinade"), and Eliot Feld ("Santa Fe Saga "). His film music includes scores for "Windjammer," " Holiday," and "Delightfully Dangerous," and his Broadway works include scores for "Billion Dollar Baby" and "Arms and the Girl. " He composed the theme music for the NBC production "Holocaust" and for ABC's "F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood, " among other TV works.

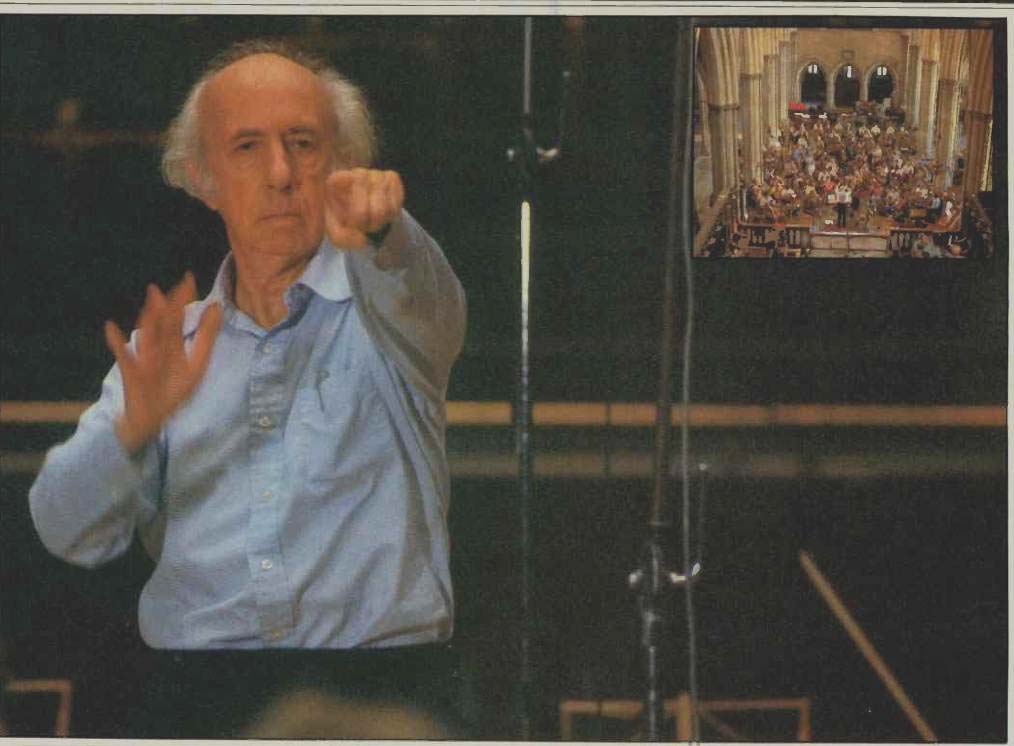

As a conductor and recording artist, Gould has been no less active. His RCA recordings of the music of Ives and Nielsen were strong influences on the growing popularity of these composers in the U.S.; he won a Grammy award for an RCA Red Seal recording of Ives' music with the Chicago Symphony in 1966. In recent years, his intimate interest in recording with the highest possible sonic quality led him to both direct-disc and digitally based records with the London Symphony and London Philharmonic Orchestras. These recordings, on the Chalfont and Varese/Sarabande labels, have made him familiar with the new technologies of digital recording and dbx-encoded discs. We visited Gould in his home on Long Island to talk about his reactions to recent developments in re cording techniques.

----

Audio: You've been exposed in the course of your career to many technical advancements in sound. In fact, you've always been noted as a composer who has taken an interest in the technical side of broad casting and recording. Of all the incremental improvements in sound that came along during your career, which was the most dramatic and large-scale?

MG: The biggest advance was the LP.

For my kind of music--which I suppose might be called symphonic music for want of a better term--the ability to do a symphonic work without having to stop after four minutes or so was a major breakthrough. There used to be a 12-inch shellac, which ran four minutes and some seconds, and then a 10-inch shellac, which ran three minutes and some thing. Even if you did a movement that ran only eight minutes, you had to break it into two segments. If it ran 10 minutes, you had to decide what to do with the remainder of the record. To say nothing of the improvement in sound, the idea of a record that could contain as much mu sic as an LP was a complete revelation.

Audio: How much music of the pre-LP era was composed specifically to fit the 78 format? Do you think the musical compositions were substantially affected by the time limitations?

MG: In the commercial sphere, a lot of things were affected. When I was making so many recordings of my arrangements of popular show tunes, they were obviously made to fit on a record side; they just could not run more than one side and be effective. I did many, many years of radio broadcasting, and in radio you rarely ran a piece more than four minutes, because in a half-hour program you wanted to do seven or eight numbers. The recording time affected many such things. What it did not affect was the serious composer who was going to write a symphony or symphonic work; however long it ran, that was it, because it was intended primarily for concert performance. The recording was simply an after-the-fact event. When you recorded it, it was your responsibility as conductor to look at the score and choose the first feasible break around the four-minute mark. Then you would attempt to stop, start again, and pick up the music.

Audio: What was the advancement that did the most to give music vibrance and "life," however?

MG: That came with the whole era of high fidelity, the accent on an increased consciousness of sound, which again was tied strongly to the advent of the LP.

This was coupled with the whole idea--also new at that time--of putting music on tape, as against the wax, and the idea that you could edit. When we did 78s, of course, that performance was it, and if there was a mistake there was no way of retrieving it.

Audio: How did the radical improvements in sound change the way you went about arranging music? For example, how did you react to the presence of wider dynamic range?

MG: The wider dynamic range made possible what might be called an expanded palette of musical colors. People could go for effects, for impact, where before it had not been possible. In the performances of individual players, you could get a wider latitude of dynamics.

Audio: With tape, did you find that performers were generally willing to take more chances?

MG: Yes, I think so. When we were doing the 78s, we all had to be careful, since there was no way to correct, while with tape you might try certain dynamics--play something louder than you were supposed to--and see if you got it on tape. You might have it on tape, too, but then not be able to make the transfer to the final disc; a certain amount of tempering was inevitable there. But at least you could try for the effect, and then if the tape or the groove broke up, do it over again or temper the transfer.

Audio: Did most composers and conductors in the early days of high fidelity take advantage of this expanded dynamic palette fully, or was it left more or less unused for a while?

MG: It took some time for people to catch up to it. You have to remember that a lot of people who recorded in those days were not particularly sensitive to the recording medium. Many of my colleagues would make comments and even write articles about how terrible re corded music was--that it was all artificial, and presented an aesthetically distorted view of music. Many performing artists wanted nothing to do with recordings. Others were allergic to the recording environment, and had to be almost pulled forcibly into the studio. There were some clear exceptions to this of course; Stokowski was doing stereo back in the Thirties. He was really a pioneer, very sound conscious.

Audio: That has also historically been said about you.

MG: Well, I think I was among those aware of it, and therefore perhaps part of the process of development. The opposition of many early performers to recording stemmed from the distortion of musical values in their eyes, rather than the technical shortcomings--though the two are of course related. An artist used to playing a tremendous fortissimo would go into a recording studio and be told "Now look, don't play it too loud." And he would begin to play a real pianissimo and be told "No, that's too soft." There developed in the first years of sound recording a breed known as the "recording artist." I was one of them.

We were people who, because of our styles or our chemistry, could adapt to the peculiarities and tensions of recording without being too thrown. Many artists unused to studios would go to pieces when that red light went on. As nervous as one might get in a concert hall, i was in a sense transient. You would leave; the music would be gone--whereas in a recording an artist could put something down and for many years afterward somebody could listen to it and comment on its faults. There were all sorts of factors that stood in the way of the performing artist relating to the re cording medium. Today every great artist is primarily a recording artist. We of ten know of artists long before we see them live, through their recordings. Long ago it was just the opposite.

The reason for this change is, of course, the whole technological area, and the constant striving for improvement, up to the digital and dbx recordings I've worked with recently--which are also radical breakthroughs. Through out my career, the problem with recording has been that it was always a mechanical medium, with its own noises, problems, and limitations. Bit by bit, the technology has widened the limits and slowly overcome the aesthetic frustrations that existed.

Audio: You're perhaps the ideal man to ask this of, Maestro Gould. There is a fair amount of debate now as to how much digital recording colors music.

Some claim that it inherently sounds false; they say that the music world is having technology for technology's sake shoved down its throat. What is your view? Do you hear intrinsic faults in digital recordings?

MG: Frankly, I wasn't aware that there was this sort of belligerence against digital recording. While I'm not fully up-to date on all of the different techniques and processes used in recording, I think that digital recording is a very important breakthrough and expansion of recording possibilities.

Audio: As big as stereo, or the LP?

MG: I would say so. In evaluating a recording's quality of sound, you must bear in mind that you have to start with what we might call a good set-up. The sound will depend on so many factors related to the set-up, no matter what kind of recording mechanism is used. It depends on the studio; it depends on the conductor; it depends on the A&R [Artist & Repertoire] man; it depends on the engineer; it depends on the weather; it depends on so many, many factors. All recordings are affected by these things, and that includes digital as well. There is no system that can automatically guarantee a first-rate recording and a good performance. You must have the appropriate ambience in the studio--especially when you're talking about big orchestra recording such as I've been involved in. You must have an engineer and technical staff who are sensitive enough to handle the orchestra's sound.

You have to have the right microphones, and the right microphone positioning.

You have to have a balanced orchestra; you can have a brilliant recording but an, orchestra that is imbalanced within itself, or even a good orchestra that just doesn't have a good whole sound. Or you can have a great orchestra and a conductor who is not sensitive and thus unable to project a performance in the studio with no audience. Assuming that all of these are pluses, and everybody knows what they are doing, digital re cording allows for a range and power that didn't exist before.

Audio: Even as compared with the best of conventional analog recording equipment?

MG: I would say so. Even most of the great analog recordings were basically illusions. With conventional recordings, you would say to the percussionists "It should sound like double forte but don't play louder than mezzo forte." You tried to give the illusion of a double forte, and of a pianissimo, but you could never really do either as they were done in a concert hall. These were all things one learned to cope with. Back in the days when virtuoso studio orchestras were assembled, they would be made up of players who knew these things. You looked at them at the appropriate moment and they knew that they had to pull back, or to play out more. When I recorded with the London Symphony using digital equipment, though, I had to first tell the percussion players to play out, not be _afraid of a sforzando or a forte. At first they looked at me as if I had two heads. They were one of the great recording orchestras of the world, yet they had never before been able to do this. From what I know now--unless there are things I haven't heard or don't know yet--digital recording is a tremendous progressive step.

Audio: Given the availability of digital and dbx techniques, among others, how do you think the musical compositions and arrangements of the future will be affected?

MG: The clearer the sonic air-and one that image-the might use more signal that can be heard and the more subtlety that can be found in the music. This cuts two ways, of course. We will certainly expose more frailties with better recordings, and where a slightly inept phrase or a passage with bad intonation might not be too evident on a record with a degree of extracurricular noise, with a better recording it will suddenly be exposed. The development of digital and of dbx which to my experience is also a tremendous contribution to pure sound-will open up a still wider palette of not only primary colors but also intermediate and inner colors, and subtle gradations of color. Any expansion of the ability to convey the color of music through the orchestral palette will ultimately be to the good. It makes us all the beneficiaries of the rich sounds that go up to make music.

(Audio magazine, Dec 1981)

Also see:

= = = =