The Beatles' producer tells the true story about why the first Beatles' CDs

weren't issued in twin-track mono.

Article author: SUSAN BOREY

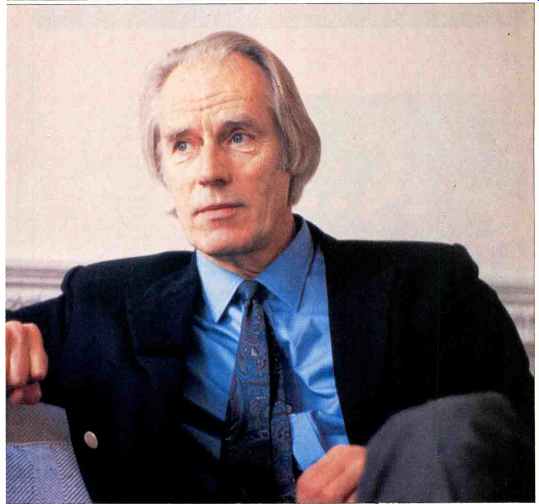

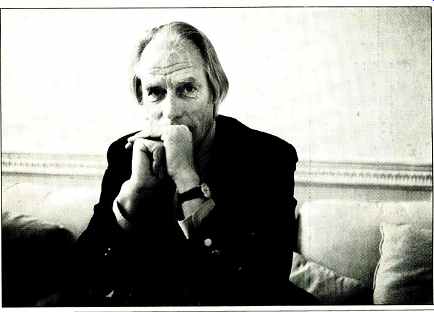

George Martin prefers not to look back. As a rule, he'd rather dwell on what's taking place today and what he might make happen next week. About six months ago, however, The Beatles' first producer was thrust into the past when EMI Music Ltd. solicited him to give a quick stamp of approval to the first four Beatles records to be released on Compact Disc (see our review elsewhere in this issue).

Finding the test tapes of Please Please Me, With The Beatles, A Hard Day's Night, and Beatles for Sale to be, in his words, "dreadful," Martin agreed to go back into the Abbey Road Studios in an effort to do the music justice.

In the process, Martin has had to sail a narrow course between the twin perils of doing too little and doing too much, showing the recordings in the best possible light while sticking to the truth of the originals. Achieving the latter has meant living with the shortcomings of the recording technology of the early '60s: Martin's first major decision was to convince EMI to release the four discs in mono, as they were originally recorded. This choice has caused a stir, but Martin remains adamant that it was the right thing to do.

Today, Martin remains involved with the CD release project, which will see eight more discs brought out by the end of this year. He is also working on a 24-part television series based on his book, Making Music. In the middle of a workday that had started at 7 a.m., he recalled his early studio experiences with The Beatles and reflected on the problems that technology has solved for the music industry-- and those it has created. S.B.

Did any of The Beatles have a hand in putting their music out on CD? No, not at all.

Do you know how any of them feel about it? Well, I haven't seen George because he is in Los Angeles. I had dinner with Paul last Friday; he has just gotten back from holiday. I asked him what he thought about the CDs. He hadn't heard them, but he said he's delighted they're putting them out this way.

How satisfied are you with the results so far? I'm delighted. I'm very pleased with what I've heard so far. I think I shall be more delighted as we go through.

Those early ones are very interesting, and historical, but I think that the real value of CD is going to be when you hear Revolver, Pepper, and beyond.

How did you become involved with putting The Beatles on CD? In December [1986], the managing director of EMI rang me up and said they were going to put The Beatles out on CD, and would I like to hear them? I said yes, and they came along and played me the tapes that they intended to put out. I thought they were dreadful, and I told them so. I said, "Okay, you have come to me and asked for my, opinion, and I've given it to you, but I can't be quiet about it. If you say you're going to go ahead with this, I'm going to tell people I think they're terrible." So I put the managing director on the spot, and he said, "Well, what do you suggest we do?" I said, "Well, get some jolly good new ones," because he was planning to put out these first albums, Please Please Me and With The Beatles, which were turned out on twin-track, in that ghastly fake stereo which was perpetrated without my authority years ago. You had all the voices on one side and all the backing on the other, and all the dirt in between them. They were never intended to be issued like that. They were mono re cords done on a twin-track machine, and I told them so. I said, "If you want to do The Beatles a favor, issue them as they were made to be, in mono." They said, "You can't have a CD in mono," and I said, "That's the way to go." I spoke to Bhaskar Menon, who's the head of Capitol, and he agreed with me completely. And that's how they were put out.

Having done that, EMI then asked me if I would take a look at the quality of the albums from then on. I've been listening to them and actually remixing--not to change them, but just to clean up the sound.

How can you clean up the sound by re-equalization ...? Yes, and by actually turning down the tracks when there is dirt on them, In those early days, when we just put out mono, we didn't pay a tremendous amount of attention to stereo. I was learning how to handle stereo in those days too. Some of those early stereo mixes I did were rubbish, but I didn't think anybody was listening. In 1963, the percentage of stereo players in this country was about 4%. Everybody listened to popular music on mono back in those days.

Has there been a big difference be tween what you've had to do with, say, With The Beatles and with Rubber Soul? Well, I didn't do anything with the first four. I did do something with Rubber Soul and with Help, which was in rather awful stereo. I had to do something to tidy up the low end of the bass and the leaking of sound from one track to another. In the early days we didn't use headphones for dubbing. We used a loudspeaker, so the separation went right out the window. For example, when we listened to "Yesterday" again-as you know, that was done with just Paul playing guitar and singing at the same time. The performance was of him playing and singing two times, and then I went away and wrote the string quartet. So the 4-track consists of Paul's voice, Paul's guitar on another track, strings on another track.

On the fourth track, I attempted to gild the lily, if you like, to get Paul to sing a better performance than he did when he sang with the guitar. In fact, I did use a little bit of that fourth track, but only in one tiny sequence, the last four notes of the first chorus. It was a sequence that I thought I had deliberately double-tracked. But it wasn't double-tracked! When I went back and listened to the tapes, I said, "No. you didn't double-track. What you did was use a little bit of the alternative voice track." And on the alternative voice track, I found that the leakage from the speaker playing the original track at the same time he is singing the new one gives the effect of double-tracking.

I took out the main vocal and brought in the alternative, but the main vocal is still in the background.

Do you think that the new Beatles CDs are valuable in part because they bring the listener closer to the recording pro cess, to hear how the recordings were produced?

I think the interesting thing is that you are hearing them now as I heard them in the studio years and years ago, with out anything getting in the way, without the fog of bad reproduction which we've always had. Now you hear the full range, you hear everything, all the mistakes included.

I have heard you say that making a record is like painting a picture. Can you draw CDs into this analogy? Yes, I can. Because of the nature of the earlier recordings, I think they were like a black and white picture. I think mono gives you that effect. As we got better, as I got better at producing The Beatles, the albums took on more life, I think that Pepper became much more colorful. We used the stereo picture with Pepper. If you shut your eyes, you can see things, or at least / can. On CD, the effect is even more dramatic.

You don't get a flat picture, you get depth as well, almost a 3-D effect.

Does the clarity of the CD present any dangers for the producer? Is the producer more exposed? Probably, but I don't think that's a danger. I think that as far as you're doing the work, you ought to be out there.

You shouldn't be frightened.

Do you feel pressured to keep up with technology by making use of every thing that's available to you as a producer? The pressure's always been there to keep up. It hasn't worried me, particularly, for I haven't found it very difficult to keep up. But I think that, in fact, technology has overtaken my desires.

In my studio in Montserrat, I've got two Mitsubishi 32-track digital recorders which are linked together, giving a total of 64 digital tracks. I've got a board that can cope with that, and all the toys that can go along with it for laying down guide tracks, drumbeats, syncing back in again, SMPTE codes, all the paraphernalia of modern technology. Which makes it easier to make records than it's ever been before, but it doesn't make better music. Better music's got to come from the heart, it's got to come from creativity. I don't think it's necessary to have the extremes of technology. It's like sitting in a comfortable chair, you know, instead of sitting in a hard-back. It doesn't make you any fitter, probably less.

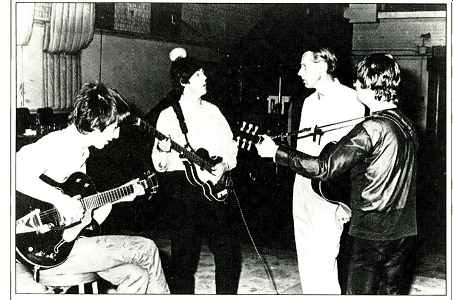

Obviously, the process of making re cords has drastically changed since the time of the earliest Beatles recordings. Do you ever miss those times? Do I yearn for those 4-track days? The only thing I yearn for is recordings that are more spontaneous. Today every thing is so clinically controlled, and everything is so meticulously accurate.

Rhythms are impeccable, ensembles are absolutely precise, intonation is perfect, not because you hear it so, but because you see it on a meter. This worries me because I think the heart is going, and I'd like to get back to humanity and mistakes.

Is there something bad about the modern process of recording, whereby members of a band don't have to be in the studio at the same time to make an album? I think there's too much of what I call layer-caking, you know, people not playing together, and technology enables us to do this. It encourages us to do this, which I think is a shame. I use technology. I have a computer here which I use a lot. I send messages, type letters, keep files, and so on. And I've got a computer at home which think is invaluable to keep myself tidy, but I use it, it doesn't use me. I think that a lot of technology tends to tell people what to do. One of the things that I've gotten to know about is performance-people playing together, making music. The interplay of people is so important. We're forgetting to do that, and I think it's a shame.

What do you think about Compact Discs in general? I think their dynamic range is wonderful. The loud bits you can hear without hurting and the quiet bits you can hear without background noise. Recording is merely a mirror of what's going on.

The CD enables us to see it more clearly. We're looking through a completely transparent pane of glass now.

Before, it was pretty cloudy.

A very interesting thing: I have a friend who's got a son of 12 who is very hard of hearing. He had meningitis when he was younger. He's always had a great deal of trouble listening to music, particularly rock or pop. He could never listen to a Walkman satisfactorily. But through a CD player and he's got a portable now-he can listen to it on headphones. He gets a great deal of enjoyment out of it and he hears much more on CD than was possible with analog tape. It's something that surprises me because I wouldn't have thought that the frequency range was that much different, particularly for his limited hearing. But it seems to work better. It isn't just a question of range. It's a question of the kind of transients that a thing is given. The sound reproduction is much more natural. I think it's delightful.

If you were recording The Beatles to day, would you record them digitally? Oh, sure. I would certainly record them digitally. I'd use all the technology that's here. But I don't think that one can look back at things and say how different they'd be. It's rather like asking, "What would Beethoven have done if he had had an 8-track machine?" Everybody uses the tools of their time. Bach used a very good organ, which was a synthesizer, you know. They only used an organ be cause an orchestra wasn't there.

Do you think there's some kind of coldness that can be attributed to digital recording? A lot of people have said this, and certainly the earlier digital recordings were. I'm not sufficiently technical to describe it. You know, digital recording has an actual ceiling, whereas analog recording doesn't. Analog recording has a frequency range which just tapers off as it gets higher, and it goes up to 100 kHz, way beyond human hearing. With digital, there is absolutely nothing above 22 kHz, no frequencies at all. There are a lot of people who claim they can hear that. I think they're mistaken. Some say they can't actually hear 22 kHz, but believe they can hear what it does to the lower frequencies. In other words, they are listening to the frequencies at, say, 15 or 16 kHz, the top end, which are colored by the absence of what would come afterwards.

What is it that makes a recording warm rather than cold? I don't know. To say it's a particular frequency would be wrong. There's no way to put it in words. It's a bit like John saying that he wanted a song to sound as though it's colored orange.

It's up to you to define those things.

Do you foresee anything like the Beatles phenomenon happening again? I do hope so. I really do hope so. I don't see it at the moment. There has been no evidence to say that, you know, Wham, or George Michael, is the new Beatles. It just doesn't add up. It's lightweight stuff.

It's awfully sad that the majority of people who are accepted as being musical giants are old men. By "old" I mean we're talking about Eric Clapton, Elton John ... even Mark Knopfler is getting up there. But they're still giants, and they're great. Amongst the kids, the 18- to 20-year-olds, there must be some great talent. I wish we could find it and encourage it. There's no evidence of it happening, however. The majority of stuff coming from young people hasn't yet benefited from the background that they have. I wonder if any of them have listened to a Cole Porter song?

(Source: Audio magazine, June 1987)

Also see:

Interview with George Martin (May 1978)

The Audio Interview: Treasured Island Chronicles: CHRIS BLACKWELL: Part I

The Audio Interview: Clive Davis: Finding Songs For Singers (July 1985)

The Audio Interview: Raymond Kurzweil--Revolutionary Tradition (Jan. 1989)

A PLETHORA OF HOLST's PLANETS (oct. 1987)

= = = =