TOP OF THE PILE

dbx-Encoded Discs For over two years, dbx has been actively engaged in producing low-priced dbx disc decoders and they have also released a wide variety of program material from a number of record companies.

The man behind this thrust is Jerome Ruzicka, the marketing head of dbx, who feels that the dbx-encoded disc might become, for the audiophile, an interim step on the uncertain path to a dig ital home music medium.

I first heard dbx-encoded discs about eight or ten years ago. I was not impressed; there seemed to be problems of overmodulation at high frequencies.

The recent standard, dbx II, which has been developed specifically for discs, has overcome most of these earlier problems. The program is equalized to give it a high-frequency rise, and it is then fed to a 2-to-1 compressor. This element in the chain compresses the signal so that, say, a 50-dB range is reduced to 25 dB.

On playback, a 1-to-2 expander restores the dynamic range, and the 25-dB signal is doubled to its original 50 dB. A complementary equalizer rolls off the boosted signal, and the original program is re stored.

When examining a dbx-encoded disc, you notice some significant differences from standard audiophile discs. We are all used to seeing the generous spacing between grooves on many standard discs (the cannon shots on Telarc's 1812 Overture are a good example), but you won't find such spacing in dbx discs because the low-frequency information has been reduced during the encoding process. As you reflect a strong light off the disc, you will be aware of the density of the signal on the disc, due both to the high-frequency boost as well as the signal compression.

While we are all used to encode/de code noise-reduction systems applied to tape recording, the application to disc is relatively recent. In tape systems, we are dealing with a predictable and constant noise level, which can be disguised relatively easily. With the disc medium, we encounter a widely unpredictable noise level--and one that is plagued with loud ticks and pops from time to time.

The dbx process is no cure-all for the usual ills of domestic pressing; a noisy dbx pressing might be okay when the music is soft (and the noise-making function at a maximum), but when the music gets loud, the ticks and pops may not be so well disguised.

You must also watch the playback level of dbx discs carefully. Because of the wide range of noise reduction, it may not be apparent just how loud things are really going to get! If you set playback level during softer passages, then over load and acoustical feedback may result when the loud passages occur. Better it is to set playback levels during the loudest passages so that your system's capabilities will not be strained. Most of the discs I have had the pleasure to preview have been excellent from the processing point of view, and it is now appropriate to look at a few of them and compare them with their standard original versions.

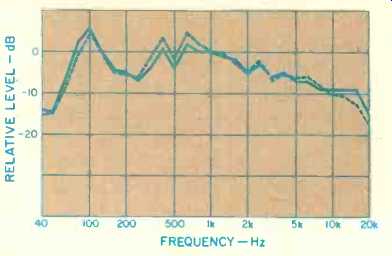

Fig. 1--Spectra for first 3:10 of "Billy the Kid." Solid line is original 1967 pressing; dashed line is for dbx version.

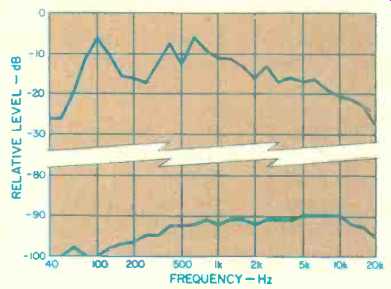

Fig. 2--Maximum dynamic range of the dbx disc. Upper curve is the peak-hold third-octave for first 3:10 of "Billy the Kid," dbx disc. Lower curve is A-weighted spectra of lead-in groove, dbx disc.

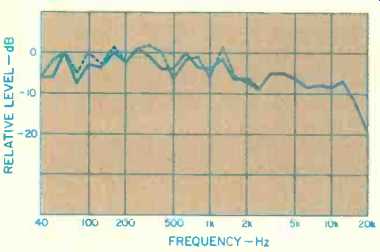

Fig. 3--Spectra of Crystal Clear organ recordings, see text. Solid line is

direct-to-disc original; dashed line is dbx version.

Early in the dbx program, Ruzicka identified a pair of discs which had be come underground audiophile favorites, the Turnabout recordings of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Donald Johanos of music of Rachmaninoff and Copland. The original re cording and disc mastering were done by David Hancock, the remarkable engineer-pianist. What had set these records apart was the integrity of a simple, two-microphone pickup with absolutely no manipulation of dynamics. Hancock re corded the works on a modified Ampex 350 at 30 ips and made the disc transfers with Ortofon cutting equipment.

While the Turnabout pressings were pretty noisy, the quality of Hancock's work was readily apparent.

Copland: "Billy the Kid," "Rodeo," "Fanfare for the Common Man." Dallas Symphony Orchestra; Donald Johanos, conductor. Turnabout TV 34169, dbx SS-3007.

Playing the dbx version, one is immediately aware that pressing noises are to tally unobtrusive; only the slight hiss level of the source tape is apparent be hind the program. Curiously, the original 1967 pressing, marred as it is by conventional pressing noises, exhibits less tape hiss. I suspect that somewhere during the last fourteen years the original Hancock 30-ips master was transferred to 15 ips, and it is that generation of tape hiss that we are hearing. In any event, the absence of pressing noise in the dbx version makes it the clear winner. (Even a bit of print-through from the 30-ips original is evident at times.) The overall tracking of the encode/de code dbx function is shown in Fig. 1.

Here, the solid lines indicate the peak-hold one-third octave spectrum of the original 1967 disc for the first 3:10 minutes of "Billy the Kid." The dotted lines indicate the spectrum for the dbx version. The broad departures in the 315 to 800 Hz range and above 10 kHz may easily be the result of subsequent equalization of the original program. All things considered, these deviations are minor (they may even be musically preferable), and they are a testimony to the accuracy of the overall process.

Even more impressive is the total dynamic range of the dbx disc. Figure 2 shows the peak-hold one-third octave spectra for the same first 3:10 minutes of "Billy the Kid" as well as the spectrum for the silent lead-in grooves of the disc (A-weighted to reflect the sensitivity of hearing for low-level noise). In the mid-band, there is a clear 80-dB signal to-noise ratio for the overall process.

Most conventional tape sources come nowhere near utilizing this capability, and only carefully made digital recordings will be able to fully demonstrate this capability. By comparison, the best audiophile product (without dbx) might exhibit a mid-band signal-to-noise ratio of 75 to 78 dB, diminishing to perhaps 65 to 70 dB at high frequencies.

Moving on to relatively recent re leases, I note with considerable satisfaction that Crystal Clear Records has made a decision to issue items from their classical catalog in the dbx format. (Not surprisingly, Crystal Clear made safety copies of their direct-to-disc projects on either analog or digital tape, often both, just for such contingencies as this.) Sonic Fireworks, Vols. I and II. Richard Morris, organ, and the Atlanta Brass Ensemble. Crystal Clear CCS-7010 and 7011, dbx GS-2021 and 2022.

These stunning albums, released in 1979, have been reviewed in these columns earlier. The dbx versions preserve the quality of the originals with no apparent degradation. And there is a bonus:

Because of the lessened demands of low-frequency modulation, greater playing time can be accommodated, and the relatively short sides of the original direct-to-disc versions have been expanded with extra pieces.

Again, the spectral tracking between the originals and the dbx versions is quite good. Figure 3 shows the peak-hold one-third octave spectra for the first two minutes of the "Grand Choeur Dialogue" by Gigout from Vol. 1. Above 1000 Hz, the tracking is very accurate.

Below 1000 Hz there appear to be small discrepancies that cannot be easily explained--unless, of course, they represent different takes, which is a distinct possibility.

There is more good news from Crystal Clear and dbx. The Virgil Fox direct-to-disc recordings made in Garden Grove, California, in 1978 have been reissued in dbx format. In my opinion, these are probably the best organ discs ever made, and I have eagerly awaited them in the new format. Here are a few capsule reviews of a number of other dbx discs:

Stravinsky: "Petrouchka," Prokofiev: "Love for Three Oranges" Suite. Minnesota Orch., Skrowaczewski, cond. Candide QCE 31103, dbx SS-3006. This is an SQ quadraphonic recording which acquits itself beautifully in stereo. Orchestral details are clearly delineated.

Recommended.

Strauss: "Dance of the Seven Veils," "Till Eulenspiegel," "Don Juan," and "Rosenkavalier" Waltzes. Cincinnati Symphony Orch., Schippers, cond.

Turnabout QTV-S 34666, dbx SS-3005. This one is a QS quadraphonic recording, and as such shows a slightly narrowed stereo perspective. The overall sound is detailed but warm.

Recommended.

Hoist: "The Planets." Saint Louis Symphony Orch., Susskind, cond. Turn about QTV-S 34598, dbx SS-3002. A beautiful recording--but the quiet pas sages are marred by a droning noise in the background. Probably the ventilating system. Apart from this, all else is lovely.

Recommended.

No noise-reduction system is without its shortcomings. Not surprisingly, these are most often apparent when the pro gram input quality is at its most demanding. For example, when a single instrument, in a solo passage, exhibits a wide dynamic range, the background noise level can often be heard exhibiting a pumping sound. When high-pitched massed strings are playing alone, one often hears a rise in low-frequency back ground noise as the shift in gain structure allows the playback low-frequency boost to emphasize more of the low-frequency noise, which is present in all discs. It a pressing has its normal share of ticks and pops, they will not be generally noticeable during soft passages.

However, at mid and high levels, the ticks and pops might become obtrusive.

The fluctuation of the noise floor may, in general, bother some listeners more than would a consistent noise floor.

These flaws are relatively minor ones for the audiophile who appreciates a wide dynamic range and who has a sys tem capable of handling the range pro vided by these discs. The thorough going purist may have other views; he may well prefer the consistent noise level of a well-produced and well-processed disc.

John M. Eargle Joy of Mozart: Midsummer Mozart Festival Orch., George Cleve, cond.

Audible Images AI-107, cassette, $17.00.

Performance: C- Processing: A Recording: C

This cassette, incorrectly numbered, I believe, since there are two No. 107s in the series, leads with the Mozart Sym phony No. 36, " Linz." Side B contains the "Divertimento in D major," K. 136.

These are not polished performances and can only be described as those of a journeyman. However, it must be said that this enterprise is reminiscent of the pioneering recording work of Westminster and Vanguard in the '50s.

The hall in which the performances were recorded was very poor; strong resonances color the sound severely. In addition, the "Divertimento" suffers from loud-level distortion which clouds the string sound, and the Linz Symphony is also plagued with distortion in the tuttis, fortes and fortissimos. The effect, subjectively, is to make the dynamics appear far greater than they are in actuality. These defects appear to be in the original recording rather than in the cassette. I used two different speaker systems, and headphones as well, to insure it was not the system itself. Very quiet cassette processing, however.

-C. Victor Campos

------

Tonwelle: Richard Wahnfried Innovative Communications KS 80006, import, stereo, 45 rpm, $10.98.

Sound: A- Performance: B+

Floating Music: Robert Schroder Innovative Communications KS 80001, import, stereo, 45 rpm, $10.98.

Sound: A Performance: A-

Hearth: Baffo Banfi Innovative Communications KS 80008, import, stereo, 45 rpm, $10.98.

Sound: A Performance: C Programm 1: Din A Testbild Innovative Communications KS 80002, import, stereo, 45 rpm, $10.98.

Sound: B Performance: B-

Synthesized and electronic music have reached unprecedented levels of mass saturation; in recent years it has ranged from the music soundtracks of PBS' "Cosmos" series and the Mercury Lynx TV commercials to the synthi-pop and Blitz/New Romantics movement in England with groups such as Gary Numan, Ultravox, Spandau Ballet, et al. But beyond these artists there is a more nearly hidden body of music where synthesizers are used to expand expression past the conventions of traditional melody, rhythm, and structure.

Klaus Schulze is one of the recognized messiahs of these new sounds and expressions, having recorded more than 20 albums and spawning a hoard of disciples over a 10-year period. In furthering his commitment to new music, Schulze has formed his own label, Innovative Communications (IC). Formerly distributed by German Warner Bros., IC recently went independent and has re leased eight new LPs, four of which I'll review here.

Richard Wahnfried is a guise employed by Schulze to collaborate with other musicians. The side-long pieces of Tonwelle (Soundpool) are dominated by insistent synthi-rhythms and Schulze's liquid cathedrals which surround the polyrhythmic drumming of Mike Shrieve (ex-Santana) and the wistful guitar of Manuel Gottsching, a cohort of Schulze's from 10 years past in the group Ash Ra Temple. Their kinetic journeys through architectural spirals of sound are sometimes distracted by the pseudo-nymned guitarist, Karl Wahnfried, and Michael Garven's brief, atmospheric, and irrelevant vocals, but never enough to derail the trip.

Robert Schroder's Floating Music is an impressive distillation of the Schulze influence. His side-long suites are intricate structures of circular melodies, shifting dynamics, and contrasts be tween the timbres of acoustic- and electronic-sounding percussion and sky-scraping whines. All of this creates a vast orchestral landscape of sound.

Two releases by Din A Testbild (DAT) and Baffo Banfi create some interesting contrasts. DAT's Programm 1 conjures up a nightmarish cityscape of careening electronic sounds and zombie rhythms.

They take themselves a bit too seriously in their lyrics, however, and the orgasm that concludes "Urwald-Liebe" is actually ironic humor that DAT misses entirely.

Hearth by Banfi goes out of its way to be humorous and sabotages some sophisticated electronics with a bump-and-twang funk rhythm section. Whimsy is fine, but do you want to hear a synthetic equivalent of Horowitz playing nursery rhymes? In order to enhance the reproduction of the synthesizer's inherently wide dynamic range, these IC records are mastered at 45 rpm. The results are more brilliant highs, snapping bass lines, and sharper definition with the sacrifice of some playing time (18 minutes per side compared with Schulze's usual 25 to 30 minute sides), and increased wear.

The original pure pressings are already deteriorating, and those pops and clicks come around a lot faster at 45 rpm. (IC records are available from Paradox Music Mail-order, 20445 Gramercy Place, Torrance, Calif. 90501.) John Diliberto unprocessed and infinitely more-real." On some of their previous efforts this has been quite revealing; for instance, on the Bob Seger Night Moves album it is suddenly apparent what a shoddy original recording this was! And The Beatles' Magical Mystery Tour and Abbey Road shine as gorgeous recordings now, with crisp drums and subtle stereo panning that were lost in the original mastering process.

Sticky Fingers, surprisingly enough, sounds like a whole new album. The dense mix now has the definition which allows the listener the ability to easily distinguish between the guitars of Keith Richard and Mick Taylor, to hear almost every lyric Mr. Jagger sings, to feel Bill Wyman's bass on "Can You Hear Me Knocking," and to fully appreciate the drum sound, which is wholly unique and perhaps Charlie's best ever. The acoustic guitars on "Wild Horses" and "Sister Morphine" are richer, and for the ultimate in lush recordings, "Moonlight Mile" deserves turning up all the way--at last. This is the kind of a record your stereo eats up alive, dishing out frequencies that you never thought it had, and although you may find you have to crank the volume more than usual due to the lack of compression, your stereo will sound more like a concert hall than a giant transistor radio.

Now if they only used this technique on all records as they are released, perhaps you wouldn't find so many records sounding great in the studio and terrible on your home system. Unfortunately, most mastering jobs are done with the three-inch speaker in mind--but at least listeners who can afford these versions do have a choice.

-Jon & Sally Tiven

Sticky Fingers: The Rolling Stones Mobile Fidelity MFSL-1-060, stereo, $16.98.

Jan and Dean Audible Images A1-103, cassette, $17.00.

Sound: A+ Performance: A

For those unaware of what goes be tween the recording of a piece of music and the playback on your turntable, be informed that the man in the cutting room plays an integral part in the finished product. He takes a raw tape and uses various filters, compressors, and noise-reduction devices in order to make the best possible presentation to his ears. Mobile Fidelity is a company that has given every listener a chance to hear a "second opinion" on his or her favorite disc by using a superior cutting technique (half speed) and the minimum number of gadgets.

What this means is that you get a wider frequency response, a far more dramatic stereo separation, more dynamic range, and a record that sounds

Performance: B- Processing: A Recording: D

This one is really painful, and since half of each side of the cassette is blank, it's a poor value overall. This is a "processed" pop recording with taped drum heads and lousy percussion; it sounds as if your ears were in the damned things. Everything is super-close miked, and limiter distortion is audible--Super Giant Mono.

The music seems to be aimed at people who grew up in California in the early '60s. While the people and music grew up, these guys didn't. And since the singers are not as talented as others from that era, nor the music as good . . .it fails, except for the processing.

-C. Victor Campos

(Audio magazine, 1981)

Also see:

= = = =