REGULATION AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT

The FCC and other federal agencies regulate the activities of broadcasters and cable-casters. No equivalent organization regulates newspapers, magazines, billboards, and books. In fact, early in the evolution of American law, a jury decision clarified the point that government must exercise care if it intervenes in the newspaper world.' Journalists and prominent individuals in the United States were concerned over the repressive power that European governments had long exercised over their publishers and hoped that America would not be forced into a similar situation.

An early case involving John Peter Zenger, a newspaper publisher, demonstrated the importance of free expression by proving that truth was a defense against a libel charge. In this case, an edition of his paper had criticized a governmental action. From this small beginning, American laws guaranteed an ever-increasing amount of freedom of speech until finally the First Amendment, which was incorporated into the Constitution in 1791, prohibited government from enacting any laws infringing upon an individual's right to publish and speak. The First Amendment made it impossible to legislate any of the editorial decisions that might confront a newspaper publisher. The government was thus restrained from creating a federal news paper commission or similar entity.

It appears contradictory, then, that the federal government created a federal agency to regulate the activities of broadcasting. After all, broadcasters are engaged in an activity that involves speech and the First Amendment protects an individual's right to say what he or she wishes. Thus, there appears to be a conflict between the FCC's involvement in broadcasting and the freedom that newspaper publishers enjoy.

But the conflict is resolved, to some extent, when one realizes that news paper publishers were never confronted with the interference and chaos that broadcasters experienced prior to the creation of the FRC in 1927. An un limited number of people can publish newspapers without interfering with any other publisher. But only a limited number of stations can broadcast before they begin to interfere with other stations' broadcasts. Wallace H. White, Jr., a congressman from Maine, observed that it is as essential to schedule use of radio frequencies as it is to schedule trains. 3 Although White's statement was made in 1922, it was not until 1927 that appropriate legislation was passed.

Later, at the fourth radio conference in 1925, Hoover observed that there were two parties using the air waves whose rights needed to be protected: the broadcaster and the public. It was, said Hoover, the public's right that should be protected. Thus, the listener should be protected against unnecessary interference, noise, and confusion on the air. The listener must be protected against the chaos of conflicting broadcasters who would make it impossible for any listener to receive an intelligible program.

From Hoover's statement evolved the notion that the air waves were the property of the public and had to be protected for the public. Thus, Hoover argued new legislation would enhance rather than violate the First Amendment rights of the listener. Of course, Hoover and others of his era were not unaware of the rights of the broadcasters. To protect broadcasters, they urged government not to create laws that would permit a federal agency to regulate the business matters of a station. Protective legislation, Hoover said, would benefit all.

The specific authority invoked for radio regulation, once the First Amendment problem was solved, derived from the Constitution-specifically the Commerce Clause (Article 1, 8), which directs the federal government to regulate interstate and foreign commerce. Since radio waves often cross state lines, radio is considered interstate commerce. The Radio Act of 1927, which was later incorporated into the Communications Act of 1934, grew from this reasoning.

Under the Radio Act of 1927, the federal government selected the most qualified applicants for broadcast licenses and awarded them a limited number of licenses to operate in the 'public interest.' The government had the authority to police the air waves for offending stations so that listeners might hear diverse programs. To secure the right to use a radio transmitter, one must acquire a license for a temporary period during which the holder is authorized to broadcast. The same is true under the Communications Act of 1934. A broadcasting license is much like a driver's license. The government holds the ...

-------------

SUPREME COURT ON GAG ORDERS

Gag orders imposed against the news media by a court may well vio late the constitutional rights of the news media. This 1976 Supreme Court decision gave the news media much more latitude in covering trials. A gag order is a restriction on coverage of pre-trial or trial in formation by the news media. These orders are issued by a judge who feels that a defendant's right to a fair trial will be affected by media coverage.

Thus, there were two conflicting constitutional rights involved in the Supreme Court's decision: the news media's right to freely print and speak as guaranteed in the First Amendment and a defendant's right to a fair trial guaranteed in the Sixth Amendment.

Some judges have felt that people who become jurors may be un fairly influenced by exposure to pre-trial coverage.

In its decision the Supreme Court held that while there may be circumstances when a gag order is necessary, they are very rare.

Indeed some of the Justices felt that there probably was no event so serious as to require a gag order. Although the decision did not absolutely forbid all gag orders, it did make the issuing of such orders much more difficult. The decision was welcomed by many members of the news media as one that would make their job of reporting news much easier.

Source: "Highest Court Loosens Gags on Trial News," Broadcasting July 5, 1976, p. 24.

-----------------

... roads as public property for all Americans. As long as one uses the roads properly, one's license will continue to be renewed. The license holder may go wherever he wishes and may use the roads in any way that is within the limits of the law, but he does not own the roads. Radio is the same. A radio station may secure a license and may use the radio waves as it wishes as long as it does not violate the relevant laws. But the radio station does not own the radio waves; they remain the property of the public and are merely loaned to a licensee.

The licensing system provides the government with a method for insuring that only those who will make the best possible use of the radio waves have ac cess to them. It is the intent of the government to be certain that every member of the public is served with some form of programming and that radio does not serve only a few.

With this concern for public benefit in the use of the air waves in mind, the FCC has created certain regulations to guide it in evaluating the performance of licensees. Some of those guidelines are discussed in the following sections of this section.

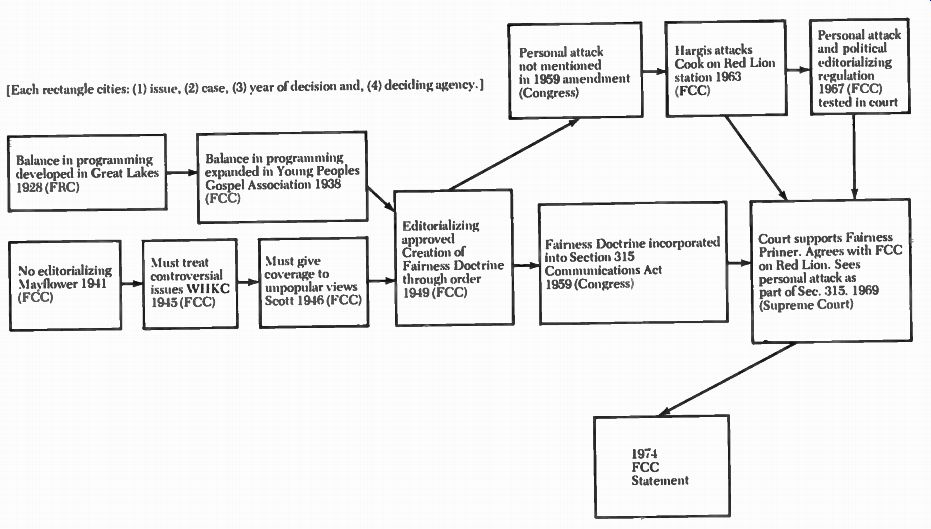

HISTORY OF THE FAIRNESS DOCTRINE

The Fairness Doctrine, one of the FCC's oldest principles, requires radio and television stations to present both sides of controversial issues. Although the doctrine was formally written into regulation in 1949, the precedents for the regulation go back to 1928 when the FRC denied a license to Great Lakes Broadcasting Company because it would not offer balanced programming. 5 In a decision of its own the FCC reaffirmed the need for balance in a 1938 case. But the 1941 the FCC decided that a licensee could not engage in editorializing, a decision that was at least partially motivated by the war and concern for divisive opinions. Then, as the second world war came to an end, the FCC began informing stations that they must make positive efforts to treat controversial issues with balance and a citizens group even got a commitment from station WHKC agreeing to a policy on controversial issues that did not discriminate against any particular group. A year later the FCC went even further by expressing the view that unpopular issues should be dealt with.° These decisions were the ground work for the Fairness Doctrine, which was written in 1949. (See Figure 11-1.) Probably the single most important element of the 1949 fairness statement was that it reversed the 1941 anti-editorial decision and permitted broadcasters to engage in editorializing. The right to editorialize, however, did not release broadcasters from their obligation to present balanced programming.

Some of the major provisions of the Fairness Doctrine are:

1. In a democracy, informed public opinion is necessary, therefore, the news media must cover the vital public issues of the day, that is, licensees have an obligation to inform.

2. The public has a right to be informed.

3. Because there is not enough time for everybody, licensees must pick and choose among those who wish to use the air. This does not mean that the licensee has the right to exclude views contrary to its own.

4. A general policy of refusing time to people with opposing views is unacceptable.

5. Two guidelines were established to aid the broadcaster in deciding whether to allot time to a spokesperson for an issue: has the viewpoint of the person requesting time already been adequately covered; and is there a better spokesperson for the view?

6. The Commission held that editorializing, in and of itself, would not necessarily make the station unbalanced in its programming. The Fairness Doctrine placed the FCC on record as supporting balanced programming when involving controversial issues of public import. The statement tended to be general and did not give the FCC strong enforcement powers, a problem that bothered Frieda Hennock, one of the commissioners.

-----------------

Each rectangle cities: (1) issue, (2) case, (3) year of decision and, (4) deciding agency.] Balance in programming developed in Great Lakes 1928 (FRC) No editorializing Mayflower 1941 (FCC) Balance in programming expanded in Young Peoples Gospel Association 1938 (FCC) Must treat controversial issues WHKC 1945 (FCC) Must give coverage to unpopular views Scott 1946 (FCC) Personal attack not mentioned in 1959 amendment (Congress) 1-01.

Editorializing approved Creation of Fairness Doctrine through order 1949 (FCC) ilargis attacks Cook on Red Lion station 1963 t FCC)

Fairness Doctrine incorporated into Section 315 Communications Act 1959 (Congress)

Personal attack and political editorializing regulation 1967 (FCC) tested in court 1.1111110 1974 FCC Statement

Figure 11-1. The evolution of four doctrines: fairness, equal opportunity,

editorializing, and personal attack.

Court supports Fairness Primer. Agrees with FCC on Red Lion. Sees personal attack as part of Sec. 315. 1969 (Supreme Court)

------------------

Yet the Fairness Doctrine was later to receive support from both the Congress and the Supreme Court. In 1959 Congress amended §315 of the Communications Act of 1934 to include the Fairness Doctrine. Then ten years later the Supreme Court, in reviewing the Red Lion case, held that the Fair ness Doctrine was a principle consistent with the Communications Act and the Constitution. Two branches of government had given their seal of approval to the doctrine as it then existed. However, the Supreme Court left open the op tion of later review of the Fairness Doctrine. In 1972, a federal court exercised that option and directed the FCC to reexamine the Fairness Doctrine to de termine if it was still needed. The resulting report was made public in 1974." Expanded Fairness Rules The first major statement made by the FCC after 1949 regarding the Fairness Doctrine came in 1964 when the FCC issued a lengthy Fairness Primer to clarify questions that might have arisen." This statement authorized any member of the public who wished to complain about a station's failure to abide by the doctrine to forward to the FCC a letter requesting its cooperation. The Commission wanted the letter to contain: (1) the name of the station involved; (2) the issue involved; (3) the date and the time the program in question was carried; (4) the basis upon which the station's presentation was one sided; (5) whether the station afforded reply time. 13 Thus individuals who wish to secure some correction through the Fairness Doctrine must do some groundwork first.

In addition, the 1964 statement listed several areas in which the Fairness Doctrine was applicable. These included: (a) civil rights; (b) political spot advertisements not involving a candidate; (e) "Reports to the People" by politicians who held elected office; (d) local controversial issues; and, (e) national controversial issues." Ten years after it released the 1964 Fairness Primer, the FCC issued another major document regarding fairness." This report was ,the result of a 1972 Court of Appeals decision instructing the FCC to reexamine the doctrine to see if changes were needed. 16 After hearings, the FCC concluded that much of the doctrine was still needed and served a valuable function.

In the 1974 statement, the FCC reminded the broadcast industry that the Fairness Doctrine was created to encourage robust discussion and that the FCC was concerned with the reasonableness of a station in handling controversial matters. The FCC used the statement to clarify its meaning of "controversial issues of public importance," the conditions that invoke the doctrine.

Public importance could be assessed by the significance ascribed to an issue by elected officials and by the amount of coverage the news media gave the mat ter. The FCC felt that the amount of public debate stimulated by an issue would be an indication of how controversial it was.

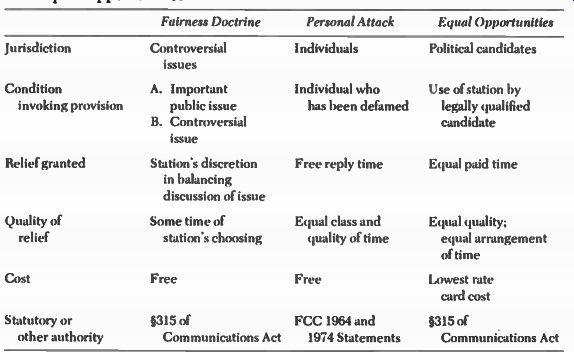

TABLE 11-1 Conditions of Three FCC Policies: Fairness, Personal Attack,

and Equal Opportunities --------- Fairness Doctrine Personal Attack Equal

Opportunities

The FCC went on to explain procedures to be followed by the licensee and by individuals involved in handling an issue. Stations, the FCC said, would be judged on their overall performance. The station must exercise diligent effort to give time to the opposing side, and the burden of finding the opposing view was on the licensee. Viewers or listeners wishing to make a fairness complaint must submit evidence indicating how they decided the station was unfair. 17 Finally, the FCC restated the principle of the Zapple Doctrine. Named after Nicholas Zapple, a Congressional lawyer who had been instrumental in getting the FCC to create the new regulation, the Zapple Doctrine applies the equal opportunities provisions of Section 315 to supporters of political candidates. (See Table 11-1.) The Fairness Doctrine-Some Problems. Over the years, many people have criticized the Fairness Doctrine as a violation of broadcasters' First Amendment rights of free speech. This view was voiced by Julian Goodman in a speech at Ithaca College in September 1976. Goodman said that many broadcast journalists are unwilling to present controversial issues, thinking that the FCC might reprove them. The Fairness Doctrine, Goodman said, prevented broadcast journalists from enjoying the freedoms that newspaper journalists have. It stifles the expression of opinion. Goodman urged repeal of the Doctrine and promised much more thorough news reporting would result.

Congress has not been unaware of the cries for repeal, and a number of bills have been introduced into both the House and the Senate, but to date no action has been taken.

Enforcement of the Fairness Doctrine Editorializing. In the Fairness Doctrine the FCC took the position that editorializing was not had or good in and of itself. In fact, the FCC held that prohibiting editorializing would not be desirable. As long as the licensee presents a fair and balanced view of controversial issues, no action would be taken to prevent editorializing.

How, then, has this policy been enforced? Perhaps the "Selling of the Pentagon" case reflects typical FCC response when it refused to take any action at all because it foresaw First Amendment problems." After CBS carried a documentary on Pentagon advertising that was critical of the practice, a Congressman wrote to the FCC suggesting that it do something about the biased point of view taken by the network. In a reply to Representative Harley O. Staggers, the FCC indicated that it was unwilling to prosecute CBS because it believed that the editorial judgments of a network should be honored in the absence of a clear and compelling indication that the broadcaster had deliberately tried to misrepresent the issues." The FCC believed it was very important that the broadcaster have a policy requiring honesty of its news staff and fairness in the presentation of news items. But FCC control over the content of news or editorials would be a violation of its authority. The FCC held that it "[could] not and should not dictate the particular response to thousands of journalistic circumstances." As a result, the FCC refused to review the decisions made by CBS. That, they held, must remain the responsibility of the licensee.

Editorial Advertising. While the FCC has applied the Fairness Doctrine to the content of programs, only occasionally has it applied the doctrine to advertising. An exception occurred in 1967 in the Banziff case. In this case the FCC found that cigarette advertising was such a national issue that it merited the application of the Fairness Doctrine. The FCC pointed out that it had no intention of applying the doctrine to other products.

Consistent with this position was the FCC refusal to consider a 1970 fairness complaint directed against automobile advertising. In a case brought by the Friends of the Earth against WNBC in New York, the FCC refused to take action, holding that the problems of automobile use-air pollution arising from the car's emissions and deaths resulting from accidents-were of such a nature that the FCC could not rule on them. A court, however, instructed the FCC to reconsider the case and held that the Fairness Doctrine might, indeed apply.

The FCC has refused to consider complaints against commercials that are intended only to advertise a product without overt editorializing. Since net works have a policy prohibiting advertisements of an argumentative or editorial nature, they restrict the whole practice of advertising. The Business Executives' Move for Vietnam Peace (BEM) was unhappy with the networks' policies and tried to get the FCC and the courts to find the network's policy illegal.

Neither the FCC nor the United States Supreme Court was inclined to reverse the networks' policies.

The Future of the Fairness Doctrine

Although the Fairness Doctrine has been accepted by both the United States Supreme Court and the Congress as a sound legal principle, many have been attacking the doctrine. For example, former Senator Sam Ervin has officially questioned the doctrine. In addition, Senators Proxmire, Pastore, Hruska, and Representatives Drinan, Thone, and Macdonald have all introduced bills that would eliminate or modify the Fairness Doctrine. The Proxmire bill would simply delete Section 315 from the Communications Act. This is the provision that covers fairness and political broadcasting.

A bill submitted by Pastore and Macdonald would remove the equal opportunities provisions for presidential and vice-presidential candidates. All of these bills were introduced during the ninety-fourth Congress and, while they have not yet been passed, they do reflect the feelings of some important members of Congress. Whether the Fairness Doctrine will survive the present attack is uncertain; however, the day may soon arrive when the doctrine is abolished.

MONOPOLY AND BROADCASTING

From the time the antitrust laws were enacted in the late 1800s, many Americans have had a fear of large corporations. First the large oil companies were broken up, then government went on to prosecute other industries including the tobacco companies. That same fear extended to the broadcast industry.

The courts have supported the FCC when it prosecuted cases against companies that were engaged in practices that tended to restrain trade. One of the first cases involved NBC and CBS. NBC owned two networks-the Red and the Blue-as a result of agreements it had made with AT&T back in the 1920s (see Section 2). CBS, on the other hand, had contracts with its affiliates that gave it the right to sell all the commercial time on the station it wished without consulting the affiliates. In return for giving up control over the station's time, the affiliates received sustaining or free programs during all of the hours the network could not sell. The affiliates were free to take or reject the time as they chose.

The Supreme Court, on the request of the Department of justice and the FCC, ruled that both agreements were unacceptable. Although the case involved business arrangements that tended to restrain trade, the court principally considered the First Amendment and "public interest, convenience, and necessity" problems. The court held that the networks had not been deprived of their freedom to speak by the new regulations and that the FCC's "public interest" mandate was a sound directive for the decision it made.

As a result of this decision NBC had to sell one of its networks. It chose to sell the Blue network, which was purchased by Edward Noble and renamed American Broadcasting Company (ABC). Thus, NBC was reduced to one net work. The same ruling forced CBS to revise its network-affiliate contract in such a way that control over its time was returned to the station." The FCC did little in the area of antitrust or restraint of trade until the 1960s when the case of WHDH-owned by the Boston Herald Traveler- arose. The Herald Traveler company owned a newspaper and radio and tele vision stations in Boston. In a 1969 decision the FCC revoked the license of WHDH-TV on the grounds that it was unacceptable for one company to own so many communication properties in one city. (In this case there was a second issue-ex parte or off the record meetings between the president of the Herald Traveler and FCC commissioners.) The WHDH case was the first incident involving what has become known as the "one-to-a-customer" rule. This rule is only one of several FCC regulations intended to encourage diversity in the field of broadcasting.

FCC Rules Designed to Promote Diversity One-to-a-Customer Rule. At present, the most controversial FCC regulation regarding diversity is the one-to-a-customer rule, which had it first test in the 1975 Washington Star case." A wealthy Texas banker, Joe L. Allbritton, wished to purchase WMAL-AM-FM-TV in addition to the Washington Star- all in Washington, D.C. Such a purchase would violate the FCC's one-to-customer rule, which prohibits a single owner from purchasing broadcast and newspaper properties in a single market. The rule also prevents the purchase of radio and television properties in the same market. During December of 1975, the FCC granted Allbritton the authority to purchase the radio and televisions stations. He had already purchased the newspaper.

The FCC agreed to the sale because it felt that Washington needed two newspapers and it appeared that the Washington Star would fold without the financial support the broadcast stations could provide. But the FCC granted Allbritton's request on the condition that he sell the radio and television stations within a specified period of time and retain only the newspaper. In addition, Allbritton would have to sell a radio and television station he had purchased in Lynchburg, Virginia. In the Allbritton case, the one-to-a-customer rule was applied to a company that wished to purchase broadcast in addition to print properties in a single large market, but the FCC has also applied the rule to individuals who already owned both broadcast and print properties. During late January 1975, the FCC ordered owners of media in sixteen small markets to sell some of their holdings.

These were newspaper-radio, newspaper-television, or radio-television owners in small markets who had created a "media monopoly," in the Commission's view.

The FCC, exhibiting no willingness to tackle media monopolies in the large markets, confined its application of the one-to-a-customer rule to small ones. The decision affected stations and newspapers in places like Albany, Georgia; Mason City, Iowa; and DuBois, Pennsylvania.

Yet in large markets there are newspaper-broadcast owners like the New York Daily News, which owns WPIX-TV. Each national television network owns television and radio stations in the same city. In 1977 a court of appeals directed the FCC to establish a policy that would break up cross-ownerships in all markets. The FCC has indicated that it will appeal the decision, thus the outcome is uncertain at this writing.

Seven-Seven-Seven Rule. The seven-seven-seven rule permits a single owner to hold up to seven AM, seven FM, and seven television stations in the nation. (Obviously, all of these stations may not be held in a single market.) The number of VHF television stations the owner may hold is limited to five. A single owner may have five VHF and two UHF, or seven UHF, or any other combination of UHF and VHF stations so long as the total does not exceed seven and the total VHF's does not exceed five. Duopoly Rule. The duopoly rule prevents an owner from possessing more than one station of a particular class in a single market. For example, a broadcaster may own only one AM station in any one market; the same applies to FM and television stations. Under this rule, it would be impossible for an individual or corporation to possess more than one television station in New York City. Networks and Anti-trust. Recently there have been many objections to the networks and their domination over local television schedules. Most television stations either subscribe to a network, receive syndicated programs that were once on a network, or both. Westinghouse Broadcasting Company has complained that it does not have enough time to program its own shows and has asked the FCC for action. The FCC has held a hearing but has formulated no new rules.

On another front, the Justice Department has filed a suit against the three networks, saying that they have a monopoly over prime-time programs. In late 1976, the Justice Department and NBC reached an agreement which would end the law suit and limit the amount of programming NBC could produce for its own use during the ten years after the agreement was signed.

But NBC was un-willing to sign the agreement unless ABC and CBS would also sign. Neither network expressed any willingness to join NBC and it appears that the suit may continue for several years.

Regulation of Socially Harmful Broadcasting Obscene and Indecent Material. One of the most difficult problems confronting the FCC and other administrative agencies is the problem of defining what is obscene and indecent and making sure that these definitions do not conflict with the First Amendment. The United States Code prohibits broadcasters from carrying anything that is obscene, indecent, or profane on the air (18 USC 1464). But the wording of this section does not define obscenity, indecency, or profanity.

In the Roth case of 1957, the Supreme Court attempted to provide some guidance for determining if a work is obscene. The important elements that resulted from the case were the Court's six criteria for evaluating obscenity.

"The standard for judging obscenity, adequate to withstand the charge of constitutional infirmity," is whether the work is obscene [1] to the average person, [2] when applying contemporary community standards, [3] if obscenity is the dominant theme of the material, [4] if the work taken as a whole is ob scene [5] when it appeals to prurient interest. 35 In addition, the work must be utterly without redeeming social value.

During 1973 and 1974 the Supreme Court evolved a new standard for obscenity. The important case was Miller v. California (1973) in which the Supreme Court spelled out three elements in deciding if a work was obscene. 36 The three tests are as follows: (1) The court must find that to the average person the work appeals to prurient interest. In this test the "community standards" must be local rather than national standards; (2) The sexual content of the work must be depicted in a patently offensive way as defined in local state law; and, (3) the work must lack serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. The Miller standard replaced the old Roth.

FCC Regulation of Obscene or Indecent Material

One of the FCC's first cases involving obscene or indecent material involved Charlie Walker, a disc jockey who worked for WDKD in Kingstree, South Carolina. According to the FCC, Walker had used off-color and smutty language on the air for a period of eight years. Because of the Walker broadcasts and other reasons, the FCC denied WDKD's application for a renewed license in 1962. In 1972 and 1973 "topless" radio became popular. These were radio pro grams in which a host interviewed callers about their sexual hangups and often went into explicit details. As a result of many listener complaints, the FCC fined WGLD-FM in Illinois $2,000 for the sex talk shows it carried in March of 1973. The NAB added provisions to its code to prevent topless radio, and stations across the country ceased carrying these shows. The topless radio fad promptly died.

In 1977 the FCC's authority to prevent the broadcast of offensive material was called into question by a court of appeals. WBAI, a radio station in New York City, had broadcast a record by George Carlin dealing with "seven dirty words." The FCC ruled that WBAI could not broadcast such material during times that children might listen to the station; however, WBAI appealed to the courts, which reversed the FCC. The FCC did not understand the First Amendment, said the court, when it ordered WBAI not to air Carlin's record during certain time periods. While this case does not deal directly with topless radio, it does point out that courts are viewing the First Amendment quite strictly.

Just as broadcasters must obey certain requirements with reference to obscenity, so must cable-casters abide by specific FCC regulations. On local origination channels-those channels on which the cable system carries its own locally produced or syndicated programs-cable operators must abide by regulations which prevent them from carrying any broadcast that is profane, obscene, or indecent. This means that they can neither produce obscene material nor can they permit others to cablecast obscene material. On channels set aside for public, educational, and governmental use--called access channels--the cable operator may also censor that which is ob scene, profane, or indecent. The cable operator must not permit access channels to be used for advertising or for carrying information regarding lotteries or political candidates.

Program Regulation

Some broadcasting regulations are based on the social effects of programming.

Perhaps the clearest example of this was the congressional action in 1972 prohibiting broadcasters from carrying cigarette advertising. The grounds for this decision were numerous studies that had found cigarette smoking to be harmful to the health.

Using the same reasoning, the FCC (1971) issued a notice declaring that song lyrics that tended to promote the use of illegal drugs were unacceptable for broadcast. The Commission held that broadcast station owners had an ob ligation to check song lyrics to make certain that they did not violate the established standards. Nicholas Johnson, one of the commissioners, emphatically protested the majority decision, saying that "it was an attempt by a group of establishmentarians to determine what youth can say and hear." One month later, the commissioners issued a second statement defending their first notice. They said that the decision was based upon the sound principle that licensees had a responsibility to control the contents of broadcasts.

Children's Programming. One of the FCC's concerns has been to protect children from programming containing scenes of excessive violence or sex.

Congress shared the same concern, and during the early 1970s it conducted studies into the effects of such programming upon children. These studies suggested that there was certainly a relationship between viewing violent programming and committing acts of violence." On the basis of those studies, Congress ordered the FCC to take some positive action to eliminate excessive violence from television.

Richard Wiley, then chairman of the FCC, saying that any regulation would be a clear violation of the First Amendment, met with the heads of the three national networks in an attempt to get their cooperation for his strategy of self regulation. The networks agreed to make the first hour of prime time--8:00 to 9:00 p.m. in the Eastern and Pacific zones and 7:00 and 8:00 p.m. in the other time zones--a family viewing period. The networks consented to reduce the amount of violence and sex shown to a level acceptable for family viewing. In addition, the NAB added provisions to extend the family viewing period through the hour preceding the networks' family hour. The two hour period following the news each evening would thus be devoted to family viewing.

On the occasional evening they carried a potentially offensive program during the family hour, the networks agreed to broadcast viewer advisories. Advisories would also be used during later hour programming that might disturb a large number of people in the audience. For these programs, the networks would forward notices to television magazines so that they might print advisories.

These voluntary decisions by the networks and the NAB constituted self regulation with government serving as a catalyst. But industry acted under the threat of FCC regulation or congressional action. Interestingly, a number of organizations and people, including Norman Lear, Writers Guild, Screen Actors Guild, and the Directors Guild, sued the three networks, the NAB, and the FCC because they felt that their right of free speech was abridged by an agreement between the networks, the FCC, and the NAB. At this writing a district court opinion agreed with the writers, but the FCC, NAB, and the net works are appealing the case.

FAILURES OF THE FCC

The FCC, as the agency that has been charged with overseeing the broadcast industry, has been examined by Congress a number of times. In fact, the FCC has been under investigation or faced the possibility of investigation by Congress almost every year since it was created. Other agencies and even its own members have scrutinized the FCC. Congress has found many problems, and at least one FCC commissioner feels that the FCC has rarely been effective. Failure of FCC to Effect Diversity of Control in Broadcast Industry Perhaps one of the areas in which the FCC has been most ineffective in regulating broadcasting is in diversity-breaking up large group and corporate ownership. In 1967, the FCC was confronted with the decision to approve or reject a merger between ABC and International Telegraph and Telephone (ITT). Had the merger been completed, ABC-ITT would have been the largest communications corporation in the world. Not only that but, according to Nicholas Johnson, the company was engaging in several questionable practices in order to persuade the FCC to approve the merger. Although the Department of Justice opposed the merger, the FCC approved the arrangement. The agreement was later called off, but the FCC had gone on record as approving an arrangement that involved questionable dealings. Only three of the seven commissioners had opposed the move.

Even the FCC's one-to-a-customer rule had difficulties from 1968 to 1975.

In 1968, the FCC proposed a new rule that would encourage diversity in ownership in a market. The rule was adopted in 1970, but it was modified in 1971 (see earlier part of this section). Little was done to enforce the rule until 1974, and then only under intense pressure from the Department of Justice.

The FCC's final decision did little more than preserve the status quo.

As a result of the pressure and public hearings, the FCC decided (1975) to force sixteen small markets to break up their media monopolies. That action is still pending. Also, in 1975 the FCC partially waived the one-to-a-customer rule by permitting Joe Allbritton to buy both radio and television stations in addition to a newspaper in a single market.

A citizens group, National Citizens Committee for Broadcasting (NCCB), believed that the FCC's one-to-a-customer rule did not go far enough. NCCB wanted the rule to be applied to all cross-ownership arrangements, regardless of market size. They also demanded that existing cross-ownerships be broken up. To get the regulation changed, NCCB appealed to the United States Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C. In 1977, the Court agreed with NCCB's argument and directed the FCC to revise its regulations accordingly. The Court of Appeals decision is being appealed, so the final outcome rests with the United States Supreme Court." Ineffective Enforcement of Decisions Not only has the FCC been slow in effecting change, it has often been in consistent in its creation and enforcement of regulations. For example during the 1940s the FCC created what became known as the "Blue Book." The Blue Book was written because the FCC felt it had a responsibility to review a broadcast station's performance in the areas of programming and commercial policy. In fact Paul A. Porter, then chairperson of the FCC, said in 1945 that the FCC would review how the program promises made by stations were met in their programming. 51 The Blue Book was created to elucidate how the FCC handled its responsibilities. The book was a compilation of situations and cases showing how the FCC had handled various applications. It covered a variety of issues including (1) competing applications, (2) hearing procedure, (3) how station promises were fulfilled in programming, (4) aspects of "the public interest" as interpreted by the FCC, and (5) commercial policy. 52 But the FCC procedures and principles were never followed largely because the broadcast industry protested so vigorously.

Ten years later, when the broadcast industry was plagued by the quiz scandals of the late 1950s and when everyone was trying to make ex parte contacts at the FCC, Jack Gould writing for The New York Times felt that it was time to bring the Blue Book back and begin enforcing the hearing and programming standards stated in the Blue Book.

Indecision in FCC Action FCC indecision, another recurring problem, probably reaches its most refined form in the cable television area where the FCC has changed its rules and regulations no fewer than three times (see Section 1). At first the FCC held that it had no regulatory authority over cable, but by 1962 it had found limited authority by regulating microwave companies that supply television programs to cable systems. The first and second cable Report and Orders in 1965 and 1966 were used by the FCC to assert extensive and repressive control over cable. Finally, in 1972, the FCC became less restrictive in its handling of cable television.

Ties of Commissioners to the Industry A problem at the FCC has been ex parte contacts between the broadcast industry and FCC officials. An ex parte contact occurs when a representative of a company under investigation meets with the FCC official in charge of the investigation in a private, off-the-record setting. Although the private meeting might not always lead to a favorable vote from the official, the possibility of influencing a decision exists.

During the 1950s, the problem was so great that the period has often been called the "Whorehouse Era"--a period when the FCC arranged actions rather than judged the facts. The off-the-record meetings, no matter what their intent, raised questions about the objective environment in which regulation was taking place. During this period lawyers hoped to get commissioners to vote favorably for their clients by offering the commissioner a gift or favor. Favorable decisions were traded for gifts.

The problem of ex parte was apparent in the WHDH case when the FCC revoked the station's license in part because an earlier chairperson of the FCC had had off-the-record contact with an executive at WHDH. The WHDH case is only one of the ex parte cases. Another involved commissioner Richard A. Mack and a Florida applicant for a station. When the record of Mack's involvement with the Florida station became public, he resigned under pressure." At least two studies have shown that large numbers of commissioners enter the communications industry or communications law practice after leaving the FCC. Few of the commissioners came from the communications industry, so it would appear that they had used the FCC as a stepping stone to the industry they had regulated. This, of course, raises questions about the public spirit of these people.

Only a few commissioners have actively worked for the public concern.

James L. Fly fought the monopoly problems in the broadcast industry in the 1940s. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Frieda B. Hennock worked for educational television allocations in opposition to the commercial interests. In the 1960s Newton Minow fought for more serious broadcast programming, and Nicholas Johnson was in the forefront of fighting for consumer interests. Yet these four commissioners represent only a small fraction of those who served the FCC.

-------------

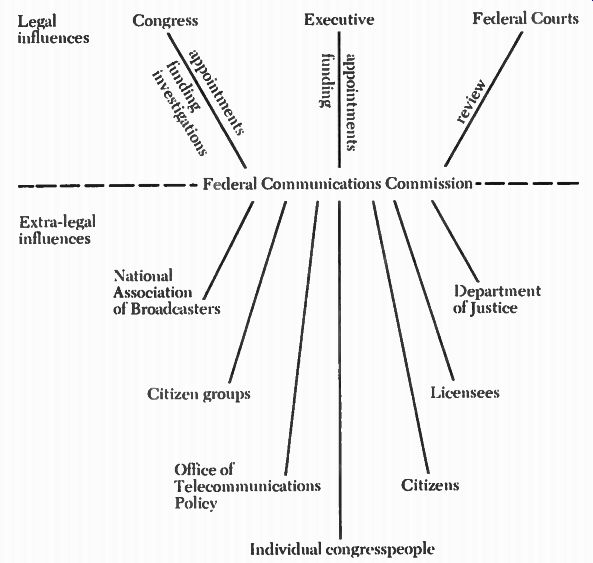

Legal influences

Extra-legal influences

Congress Executive

Federal Courts

Federal Communications Commission

National Association of Broadcasters Citizen groups Office of Telecommunications Policy Department of Justice Licensees Citizens Individual congress-people

Figure 11-2. The supercharged political environment in which the Federal

Communications Commission operates. Each of these groups has an interest

in influencing FCC actions.

------------------

Although the FCC was designed to be free of other governmental pressures in the execution of its duties, the freedom which it has is more of an illusion than a reality. In the wilting of the Communications Act of 1934, Congress retained the power to approve or reject the annual budgets of the FCC, to amend the Communications Act, and to review the decision and rules of the FCC. Congress gave the President both the right to appointcom missioners and to disburse funds to the agency and, as ordered by the Constitution, Congress gave the courts the right to review every action of the FCC. These powers give the three branches of government great control over the daily actions of the FCC. (See Figure 11-2.) In addition to the legal forces, there are intense political forces trying to influence the FCC. The broadcast industry, through its rich and powerful trade lobby association, the NAB, urges the FCC to make decisions favorable to the broadcast industry. Citizens groups frequently demand that the FCC listen to their protests. Individual congressmen may, at the urging of their constituents, call commissioners to "suggest" changes in policy.

Because of the intense political pressures, the FCC not only must conform to the law, but it must also balance favorable and unfavorable political forces. 55 Only by maintaining this balance can the FCC have some semblance of freedom of choice.

PROPOSALS FOR IMPROVING THE FCC

Numerous methods for reforming the FCC have been advanced, each with merits. Some of these proposals are discussed briefly in the following sections.

Insulation from Political Influence

As has been noted above, the FCC comes under considerable political influence from the Congress and the Executive. If the agency is to work effectively, it should be given freedom from excessive external intervention so that it need not fear the anger of a Congress or a President. This, some feel, can be accomplished by lengthening the term for commissioners, including, perhaps, life tenure on the FCC as for judges in the courts. Separate Functions Dividing the legislative and judicial roles of the FCC between two agencies might solve some of the agency's problems. That way the new agency responsible for enforcing the regulations would not have the power to modify regulations for its convenience.

License by Lottery

Most applicants who apply to the FCC for a license have met the minimum qualifications for holding a license since the first action of the FCC is to weed out those who fall short of minimum requirements. The qualifications and proposals of the applicants for a channel are usually very similar. Consequently, the awarding of the license becomes an exercise in looking for minute details that may distinguish one applicant from another. Such a process necessarily gives much work to lawyers, but may prove of little overall benefit to the viewing and listening audience.

Because applicants do not differ significantly, Richard Wiley, then chair person of the FCC suggested in a speech before the NAB in 1976 that licenses be awarded on the basis of lottery. Thus when several applicants who meet the minimum qualifications for holding a license apply for the same channel, the winning applicant's name would be drawn at random or would be chosen by computer. Although this process lacks the apparent precision of the more traditional method of conducting hearings on the qualifications of applicants, it is clearly faster and cheaper. Of course, no one can be sure that it is better for the consumer of the mass media.

Such a revolutionary procedure probably will never receive Congressional support--and it may not even have serious support from Wiley who proposed it--but it does reflect the problems the FCC faces when trying to decide among a group of nearly equal applicants.

Citizen Participation

One author properly observed that "without the sustained interest of a majority of the voters, the public interest is neglected and a regulatory agency is ripe for capture by the regulated groups." Washington is a political city where laws and regulations are created in an environment of intense political competition. Lobbying is just as common on Capital Hill and before the Executive as it is before the FCC. Much of the regulatory chaos results from this lobbying--or at least from an unwillingness to admit its existence.

Because of the nature of the regulatory environment, the most promising reform may come from the active involvement of citizen groups like the National Citizens Committee for Broadcasting (NCCB). Like the NAB, which lobbies for the interests of broadcasters, NCCB lobbies for the interests of citizens.

These competing forces must eventually force the FCC to begin balancing the demands of citizens against those of broadcasters.

-------------------

LAW OF EFFECTIVE REFORM

Citizen groups must follow certain procedures if they wish to get effective action from the FCC. To help people who have little experience in appealing to the FCC, Nicholas Johnson has created what he calls the "law of effective reform." According to this principle, there are three steps that one must complete. They are:

1. State the facts in the situation that provide the basis for thecom plaint. These facts must be carefully and accurately spelled out.

2. Cite the appropriate legal principle that provides for relief. This includes FCC rules and regulations, appropriate statutes, court cases, and constitutional provisions.

3. Clearly spell out the remedy or correction desired: a fine, re vocation of a license, or a change in programming.

Source: Nicholas Johnson: How to Talk Back to Your Television Set (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1969), p. 202.

-------------------------------

NOTES

1. Edwin Emery, Philip H. Ault, and Warren K. Agee Introduction to Mass Communication, 3rd ed. (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1971), pp. 38, 99.

2. Ibid.

3. Walter B. Emery, Broadcasting and Government (East Lansing; Michigan State University Press, 1971), p. 27.

4. Ibid., pp. 28, 29.

5. Great Lakes Broadcasting Company, Fed. Radio Comm., D. 4900 (1928).

6. Young People's Association for the Propagation of the Gospel, 6 FCC 178 (1938).

7. Mayflower Broadcasting Corporation, 8 FCC 333 (1941).

8. United Broadcasting Company, 10 FCC 515, 5 RR 799 (1945).

9. In re Petition of Robert Harold Scott for Revocation of Licenses of Radio Stations KQW, KPO and KFRC, 11 FCC 372 (1946).

10. In the Matter of Editorializing by Broadcast Licensees, 13 FCC §246 (1949).

11. Red Lion Broadcasting Co., v. FCC, 395 US 367 (1967).

12. Applicability of the Fairness Doctrine in the Handling of Controversial Issues of Public Importance, 29 Fed. Reg. 10415 (1964).

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Fairness Doctrine and Public Interest Standards--Handling of Public Issues (1974).

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. In re Complaint Concerning the CBS Program "The Selling of the Pentagon," 30 FCC 2d 150 (1971).

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Letter from Federal Communications Commission to Television Station WCBS TV 8 FCC 2d 381 (1967).

23. Friends of the Earth v. FCC, 449 F.2d 1164 (D.C. Cir.) (1971).

24. National Broadcasting Company, v. United States 319 US 190 (1943).

25. Ibid.

26. Sterling Quinlan, The Hundred Million Dollar Lunch (Chicago: J. Phillip O'Hara, Inc., 1974), pp. 111-116.

27. "Allbritton gets his Deal for Washington," Broadcasting ( December 22, 1975), pp. 19, 20.

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid.

30. "FCC at last Defines Policy on Broadcast and Newspaper Cross ownership," Broadcasting (February 3, 1975), p. 23.

31. Ibid.

32. FCC, 38ffi Annual Report/Fiscal Year 1972 ( Washington: Government Printing Office), p. 42.

33. Ibid.

34. Roth v. United States 354 US 476 (1956).

35. Ibid., 354 US 477.

36. Miller v. United States 413 US 25 (1974).

37. Ibid.

38. Palmetto Broadcasting Company, 33 FCC 250 (1962).

39. 41 FCC 2d 919 (1973).

40. 47 CFR 76.215.

41. 47 CFR 76.251.

42. Ibid.

43. Frank J. Kahn, Documents of American Broadcasting (New York: Appleton Century-Crofts, 1973), p. 434.

44. Licensee Responsibility to Review Records Before Their Broadcast 28 FCC 2d 409 (1971).

45. Ibid.

46. Report on the Broadcast of Violent, Indecent and Obscene Material (Washington, D.C.: FCC, 1975), pp. 1-3.

47. Walter B. Emery, Broadcasting and Government (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1971), p. 396.

48. Ibid.

49. Nicholas Johnson, How to Talk Back to Your Television Set (Boston: Little, Brown, 1969), pp. 49-59.

50. Government Widens Attack on Newspaper, Broadcasting Cross-ownership, Broadcasting, January 7, 1973), p. 16.

51. Freedom of Information Center, FCC's "Blue Book- (1946) (Columbia, Missouri, December 1962), p. 1.

52. Ibid.

53. Quinlan, op. cit., pp. 1-14.

54. Ibid., pp. 5, 6.

55. Erik Barnouw, A Tower in Babel (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966), p. 251.

56. Erwin Krasnow and Lawrence D. Longley, The Politics of Broadcast Regulation (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1973), p. 9.

57. "Wiley Offers New Order for Licensing," Broadcasting (March 29, 1976), p. 24.

58. Marver H. Bernstein, Regulating Business by Independent Commission (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1966), p. 285.