In the early days of broadcasting, no distinction was made between educational and commercial stations, in fact, in 1925, 171 educational institutions and organizations were operating AM broadcast stations. As interest in broadcasting grew, however, the commercial broadcasters began to take over the educational broadcaster's licenses. Since many educational stations could not afford to run broadcast stations, especially during the depression, they put up little resistance and by 1937 the educators only held licenses for thirty-eight stations. In deciding on early radio regulation, Congress was uncertain about the role of educational broadcasting. When it debated the revision of the Federal Radio Act of 1927, one of the main considerations was whether a certain percentage of channels should be reserved for educational use. Since no educators insisted on reserved educational channels and since such a reservation would have meant a delay in passing the Communications Act of 1934, Congress passed the Act without reserving educational channels. In 1935 the newly instituted Federal Communications Commission (FCC) stated that the commercial stations would provide enough chances for educational programming and, thus, there was no need for separate educational channels.

The belief that commercial stations would fulfill educational needs proved to be overly idealistic. Although stations and networks began by offering educational programming, it soon became a negligible part of their programming schedules. The idea of educational programming remained mainly rhetorical--many commercial broadcasters thought it was a fine idea but few did anything about it.

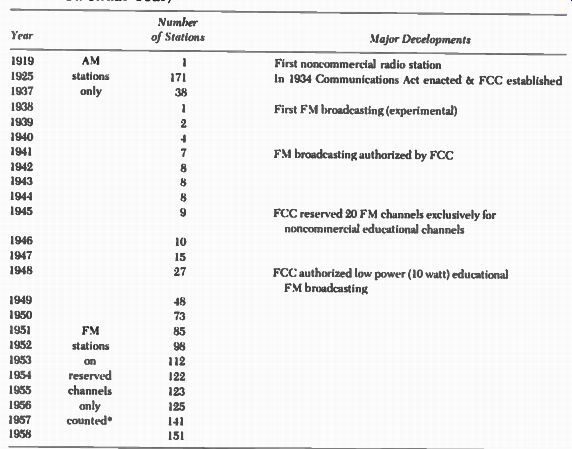

In 1940 the FCC realized that if educational programming was to exist it would have to create separate educational channels, therefore, the commission created five FM channels for noncommercial educational broadcasting. 2 These five channels were increased to twenty in 1945 when the FCC decided to change FM allocations to a higher band. This was the beginning of a steady growth in educational FM radio as can be seen in Table 6-1. In 1948 the FCC gave even more broadcast power to educational institutions when it authorized low-power ten watt stations for noncommercial use, thereby creating many of the stations that are used by schools, colleges, and universities today.

Although FM broadcasting is now well established, in 1945 the allocation of FM channels to educators was no great advantage to the recipients since few people had FM receivers. Thus, many stations existed for years with very few listeners. When FM began to grow, however, these channels became more valuable. Also, the principle had been established that government should set aside channels for non-commercial broadcasting-a principle that became even more important when it came time to allocate television channels.

TABLE 6-1 Growth of Noncommercial Radio Stations: 1919-1973 (at the

End of Calendar Year)

------------- From 1938 to 1968, the number of stations includes

those stations broadcasting on reserved FM channels for educational broadcasting

only. Source: Federal Communications, "Educational Television,”

Information Bulletin, April, 1971, p. 5 and CPB.

**Number in parentheses indicates the number of stations qualified for CPB's Source: S. Young Lee and Ronald J. Pedone, Status Report on Public Broadcasting, (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1975), p. 8.

When the reserved FM channels became available to the educational broadcasters, it was clear that educational radio might have a future. The National Association of Educational Broadcasters (NAEB) received foundation grants which enabled it to set up a radio tape mail "network" and to make grants for program series. The tape network was particularly useful since it enabled radio stations throughout the country to exchange programs.

Early in the 1950s it was clear that if the educational broadcasters wanted to get into television they were going to have to make some systematic and organized demands. Accordingly, in 1950, the NAEB and the U.S. Office of Education formed the Joint Committee on Educational Television (JCET)--a committee made up of a variety of collegiate and educational associations. The main function of JCET was to represent the interests of the educational broadcasters before the FCC. Although the FCC had already allocated some television channels in 1948, the commission froze further television allocations while it determined the best system of allocations for the entire country (see Section 3). The freeze gave educators the opportunity to propose that some of the television channels be reserved for educational use.

Although there was little opposition to reserved educational channels, members of JCET felt that their case would be even stronger if they could show that commercial broadcasters were not providing well-rounded programming.

They gathered their evidence by monitoring commercial television offerings in several cities. The New York City viewers alone found that there were 2,970 acts or threats of television violence in a single week-many of them occurring when children were likely to be watching. Many people were shocked by these results and felt that they clearly indicated the need for an alternate system. 3 When the freeze ended in 1952, it was clear that JCET had been successful; the FCC set aside 242 channels (80 VHF and 152 UHF) channels for educational use. By 1974 the FCC had revised the Table of Allocations and the number of noncommercial channels was increased to 672 (132 VHF and 540 UHF).4 Although the educators had their channels it was again apparent that the FCC had not been overly generous. As in the case of radio, the educational broadcasters were second to the commercial broadcasters. They did not receive channels in several major markets ( New York, Philadelphia, Washington) and most of the channels they did receive were UHF-at a time when few persons had UHF receivers. Again, the situation was somewhat improved in later years; some of the educational interests were able to obtain outlets in major markets by buying existing commercial stations, and the receiver situation improved when Congress ruled that after April 30, 1964 all new television receivers must be equipped to receive both VHF and UHF. Although the allocation of reserved channels had been a major hurdle for educational broadcasting, there were many more problems to be solved. The major issue was money to finance the new broadcast operations. Many educational institutions helped to support their own broadcast systems, but the principle source of funding was the Ford Foundation.

The Ford Foundation played a key role in educational broadcasting in broadcasting's earliest days by providing funding both for stations and pro grams. The Foundation also provided a $1 million grant to establish the first television mail network. The "network," the Educational Television and Radio Center (ETRC) located in Ann Arbor, Michigan, duplicated and distributed programs to stations across the nation. In 1959 ETRC moved to New York, and in 1963 changed its name to National Educational Television (NET). At this point NET also changed its direction; it dropped its distribution function and began to produce programs of its own with additional funding from the Ford Foundation. 5 NET programming did much to advance the prestige and influence of educational television.

Although the Ford Foundation funding was invaluable to the development of educational television it was clear that the Ford Foundation--even when its resources were combined with other public and private sources-could not continue to support educational broadcasting indefinitely.

In 1962 the federal government began to take on some of the responsibility for funding with the Educational Television Facilities Act. This Act authorized the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to provide federal funding to applicants to construct and expand broadcast facilities. During this period the number of noncommercial television stations either going on the air or under construction increased from 76 to 239. In the five years that radio stations were eligible for grants, they received forty grants to construct new stations and sixty-four grants to expand existing ones. 6 The Educational Facilities Act was a tremendous incentive to the development of noncommercial broadcasting. In a sense, however, the Act created stations that were "all dressed up with no place to go." Stations had new buildings, new studios, and new equipment but the Act provided little money for programming. Another problem was that there was still no interconnection between NET stations.

In 1967, a solution to the continuing problem of funding for educational broadcasting was tackled by the Carnegie Foundation. The Foundation set up a committee known as the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television. The Commission, made up of representatives of government, business, the broadcast industry, and education, was given the responsibility of making a comprehensive study of the future of educational television, and of making recommendations to President Lyndon B. Johnson.

After studying the problem the Commission recommended, in 1967, that federal, state, and local government should provide facilities and adequate sup port for educational television and that Congress should establish a nonprofit, nongovernmental corporation to oversee the operation.

In February of 1967, President Johnson requested specific legislation based on the Commission's recommendations. During the same year, Congress passed the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, the Act then becoming part of the Communications Act of 1934.

As well as extending the Educational Facilities legislation for another three years, the Public Broadcasting Act authorized the establishment of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). CPB was set up as a nonprofit, non political corporation with a Board of Directors consisting of fifteen members appointed by the President of the United States. The act stipulated that no more than eight members could be from one political party and that the term of office would be six years. Congress also prohibited CPB, and indeed all noncommercial stations, from editorializing or supporting or opposing any political candidate. The Act states that CPB responsibilities are to help develop programs, obtain grants from private and governmental agencies, to distribute these grants to stations for program production and services, and to set up the interconnection between stations.

Once CPB was established and funded, one of its most important jobs was to set up the interconnection, or network. To this end CPB established and funded the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) to provide an interconnection for television, and a few years later it created National Public Radio (NPR), an interconnection for radio. Once PBS was established, there was no longer a reason to operate the NET mail network. Consequently, NET merged with the public television channel, WNDT in New York City, and it took WNET as its new call letters.

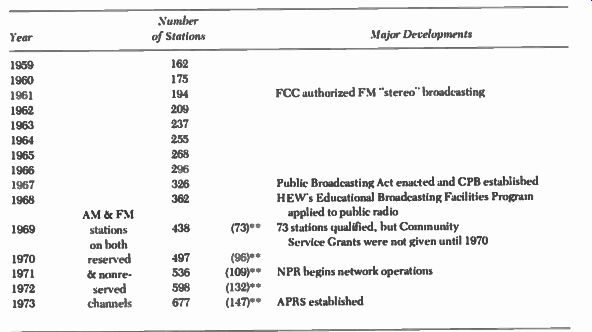

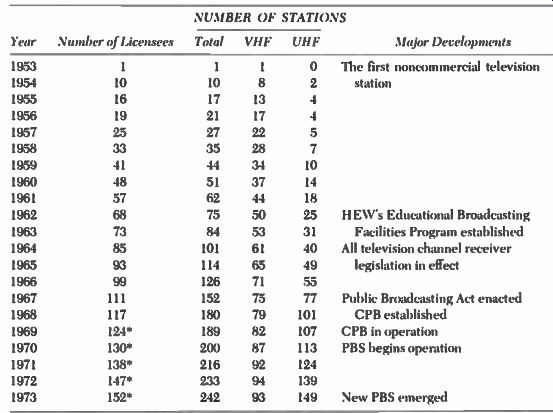

TABLE 6 - 2 Growth of Public Television Licensees and Stations: 1953-1973

(at the End of Calendar Year) ----------

*Includes stations operated independently from the parent licensees" operations: one such station for 1969 through 1972 and four for 1973.

Source: S. Young Lee and Ronald J. Pedone, Status Report on Public Broadcasting, (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975), p. 13.

Both the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 and the Educational Facilities Act of 1962 were responsible for many new stations going on the air. As can be seen by Table 6-2, 1967 began a major growth period for public television, although it was not long before the public broadcasting system encountered some major problems. The first big crisis came in 1972 for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Despite overwhelming Congressional support for CPB appropriations, Richard M. Nixon, then president, vetoed the bill. Basically Nixon had two objections to CPB: he felt that it was supporting news and public affairs programs that were biased, and that it was becoming too powerful and centralized. Nixon believed that CPB was creating a fourth network whose power was centered in the Eastern cities-particularly New York and Washington. Instead he favored grassroots participation; a system in which all local stations would participate in the programming and decision-making process.

Some who were involved in public broadcasting believed that Nixon's at tack, especially in reference to CPB centralization, was justified. The public broadcasters had already been divided over whether public broadcasting should be centralized or based more on local and regional needs.

There was also a power struggle between CPB and PBS. Although PBS had originally been established to provide the interconnection, it was also making important decisions about scheduling and programming that, in the opinion of CPB, overstepped PBS responsibilities. Finally a compromise was worked out in 1973: PBS and CPB reached an agreement that provided PBS with the right to choose and schedule programs and CPB with the right to oversee and object to PBS choices.

Although there was never a very specific decision made as to whether public broadcasting would be national or local, a compromise was reached giving local stations a greater role in providing and choosing programs than they had previously had. The issue of bias in news and public affairs programming was not so easily solved. The first president of CPB, John W. Macy, had resigned in protest because of the Nixon administration's interference with programming. Thus, it became clear that public broadcasting was vulnerable to political pressure and, consequently, the public broadcasters reduced the number and intensity of controversial news and public affairs programs.

Although many stations, which had been previously considered educational, became public broadcasting stations, the education designation did not entirely disappear. However, the term -educational- is more useful to the FCC than it is to the general public.

The numerous noncommercial radio stations that are not part of public broadcasting bear very little resemblance to each other. They range in power from low power FM stations to stations with power equivalent to commercial FM stations. Programming formats range from Top 40 to classical music. Economic support for educational radio ranges from colleges, which pay the entire bill, to municipal, state, or local sources. There are also noncommercial stations that are supported by listeners and foundations. The Pacifica Foundation is an example of a group that runs radio stations of this nature.

The only noncommercial educational stations that share common programming and economic characteristics are part of the public broadcasting system.

We will limit our discussion to the public television stations that are affiliated with PBS, and the public radio stations that are affiliated with NPR, and the operations and policies of these networks and stations.

TABLE 6-3 Percentage of Cash Income of Public Television Licensees by Source, 1974

THE ECONOMICS OF PUBLIC BROADCASTING

When radio and television frequencies were reserved for educational use the FCC stipulated that stations that used these frequencies must be run as non commercial operations. This meant that noncommercial stations had to find an alternative source of money to keep the system in operation.

Although the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 provided federal funding, the support was always inadequate for all the needs of public broadcasting. In the beginning, the federal government paid almost half of the funding for organizations such as CPB, PBS, and NPR, while it paid less than 10 percent of the cost of running individual radio and television stations.° Obviously then, public broadcasting funding depends on several agencies and institutions in addition to the federal government. In Table 6-3 we can see the sources of cash income for public television licensees for 1974. In the following section we will examine these funding categories in greater detail.

Federal Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). When Congress makes its yearly appropriation to public broadcasting the money goes to CPB. CPB then channels this funding to the various institutions and organizations involved in public broadcasting. A portion goes to the television network, PBS, to be used for the interconnection between stations and to assist in program scheduling.

The radio network, NPR, receives funding for interconnection, programming, and promotion.

CPB also distributes a substantial portion of the money to individual radio and television stations in the form of Community Service Grants. Stations are free to use these grants as they please and commonly use them to produce or purchase programming.

Another portion of the CPB money goes for program development. CPB will fund pilot programs and program series intended for national distribution for a two year period. If producers want to continue their program beyond this point they must find other funding sources. The remainder of CPB money is used to support a research office and to maintain its own offices and staff.

Federal Grants. As well as the annual congressional appropriations which are made to CPB, the federal government has made program funding available through various government agencies. Agencies such as the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts have sup ported a good deal of cultural public television programming. The Children's Television Workshop, which produces " Sesame Street" and -The Electric Company, - has received a portion of their funding from the U.S. Office of Education.

State and Local Government Funding The single greatest source of money for public broadcasting comes from state government. States have a variety of ways of supporting public broadcasting.

Some states fund a state educational network or individual stations with money appropriated directly by the state legislature. Other states channel money to public broadcasting through the state board of education. States also support colleges and universities-many of which run public broadcasting stations.

Many local schools and local governments also contribute to the support of public broadcasting. Local schools are most likely to give financial support to stations when the station's programming is used in the classroom for instructional purposes.

-----------------

PROFILE OF A LOCAL PUBLIC TELEVISION STATION

Although there is no typical public television station, WITF-TV is a station that represents some of the triumphs and problems of public broadcasting. WITF is owned and operated by the South Central Educational Broadcasting Council. Its signal reaches a 10-county area of South Central Pennsylvania and it is a member of the Pennsylvania Public Television Network, which serves the entire state.

WITF began operations in 1964 with a budget of a quarter of a million dollars. By 1975 their yearly budget exceeded $1 million.

Twenty-eight percent of their budget for the 1975-76 season came from the state network, which is funded by the state legislature.

Twenty-one percent came from grants and foundations, 18 percent from fund raising efforts, 15 percent from the school district, 11 percent from CPB, and 7 percent from the Pennsylvania Department of Education.

WITF has been successful in producing programs that have been carried on the PBS interconnection. Although this is expected from larger stations in cities such as New York and San Francisco, it is not very common for small and medium-market stations. Since its beginning WITF has received program grants from the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, the Ford Foundation, and CPB, just to name a few.

The annual budget of WITF would not begin to pay for a single evening of commercial network prime time programming. Yet it is stations such as WITF that are able to provide both innovative and creative programming-even on a very limited budget.

-------------------

Foundations

Several private foundations have supported both educational and public broadcasting throughout the years. Their money has been used for programming, equipment and facilities, and research. Substantial contributions have come from the Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Markle Foundations. The greatest contributor of all has been the Ford Foundation-contributing over $268 million to educational broadcasting between 1951 and 1973. 9 Foundation funding, however, may be less of a factor in the future support of public broadcasting. Between 1973 and 1974 foundation grants to public tele vision decreased by 14.5 percent. This was the only funding category to decrease during this time period. Corporate Underwriting Several private corporations have taken on the responsibility of underwriting public television programs. Notable programs made possible by partial or total corporate underwriting are "Upstairs, Downstairs" and "The Adams Chronicles." Programming that is underwritten by corporations is inexpensive for the local station since the station only has to pay a portion of the cost of acquiring the program from the network. Consequently, practically all PBS stations carry these programs. Although underwriting corporations get only a brief line of credit, they generally gain a great deal in terms of public relations.

Although there has been little abuse of corporate underwriting there is concern that corporate influence may interfere with program content. PBS has developed guidelines for private underwriters that are designed to limit their control over programming.

-------------

WHO WATCHES PUBLIC TELEVISION?

According to a 1975 Roper study, when the public television audience is compared to the population at large, the PTV viewer is:

-more likely to have a college education and income over $15,000

-more likely to live in the Northeast, Midwest, or West

-slightly more liberal in politics

-more likely to be female (55 percent)

-likely to be between 22 and 44 (53 percent)

-overwhelmingly likely to be white (93 percent).

Source: CPB Report, February 2, 1976

-------------

Individual Station Fund Raising

As any public broadcast viewer or listener knows, stations engage in a good deal of individual fundraising. Most stations have at least one full time person and many volunteers whose sole responsibility is to promote the station and raise money. This effort pays off for the station--a good fund raiser may raise anywhere from fifteen to thirty percent of the station's total budget.

The major fund raising effort usually comes from membership drives during which the station tries to secure commitments from members of the viewing or listening audience for annual pledges of money. In return for a pledge, members have a sense of direct participation in station affairs and, in most cases, they also receive a monthly program guide. Many stations also run a successful yearly auction. Local merchants donate merchandise throughout the year and the stations take a few days of prime time programming to auction the merchandise to its viewers and listeners.

Most stations also take on the responsibility of raising programming money by applying for grants to produce programming. These grant proposals are sent to a variety of organization including CPB, private foundations, and business and industry.

TABLE 6-4 Operating Costs of Public Television Licensees, by Percentage,

1974 Source: CPB Report, December 15, 1975

TABLE 6 - 5 Program Sources for Public Television, 1974 by Percentages

PROGRAM SOURCES AND FUNDING

As we have seen, public broadcasting depends on a variety of sources for funding. Table 6-4 shows how public television stations use their money. Programming, combined with the interrelated technical and production categories, uses almost two-thirds of the total budget. Therefore, most of the focus of fund raising is for programming.

Program funding comes from federal, state, and local government; business and industry; private foundations; and public broadcasting audiences. Some times a single source will fund an entire program series. However, it is much more characteristic for program funding for a series to depend on several sources. In the discussion that follows we will describe some of the principle types of arrangements that public broadcasting uses to produce and acquire programs. A breakdown of the sources of programming to individual stations can be seen in Table 6-5.

Programs Carried on the PBS Interconnection

The Station Program Cooperative (SPC). Unlike the commercial affiliates who depend on the networks to make programming choices, public television stations have a voice in network decision making about programming. This station involvement began in 1974 when CPB and the Ford Foundation provided funding to PBS to set up and administer the Station Program Cooperative (S PC). The Cooperative offers all public television stations the opportunity to buy and submit television programs. Any station that is interested in producing a program or program series submits a proposal to the Cooperative. PBS puts these proposals into a catalog that is circulated to all member stations. Stations then indicate the programs in which they are interested. The programs in which stations have no interest are eliminated and then stations make their purchases from the remaining programs.

The money that a station uses to acquire a program series must come out of its own budget. Some stations depend almost entirely on their CPBcom munity Service Grants to buy programming. Other stations with aggressive fund raising departments will be able to use some of this income to buy pro grams. A smaller station with limited funds might only be able to afford the cheaper series.

At the time of this writing, the Cooperative is partially subsidized by CPB and the Ford Foundation. This means that these two organizations pay a portion of the production costs and the stations that desire the program series di vide the remaining costs of production among themselves. However, both Ford and CPB plan to eventually phase themselves out of the Cooperative, which means that programming offerings will cost more to the individual television stations. CPB plans to offset this increased cost to stations by offering stations larger community service grants.

Programs do not have to be chosen by all stations (or even a majority) to be scheduled by PBS. The more stations that choose a program the lower the price since the production costs are then divided among a larger number of stations.

If only a few stations choose an expensive program the corresponding price might be so high that stations would eventually decide that the program would not fit into their budgets. The stations would decide not to carry the program and it would, therefore, be dropped by the Cooperative.

The Cooperative is not without critics. Supporters believe that this system enables local stations to better serve community needs and that the system encourages local decision making. Critics believe that cheap programming will drive out expensive programming. For example, it is cheaper to produce exercise and cooking shows than it is to produce documentaries and operas.

Another criticism is that controversial public affairs programming will not fare well when put into the marketplace and left to individual station determination.

Others maintain that stations are more willing to purchase programs produced by bigger, well-known stations in urban centers, whereas they are afraid to risk programs from smaller, lesser-known stations. Regardless of one's position, the Cooperative has been a way to decentralize programming and it will probably continue to be the system by which most of the programming is chosen to be carried.

Individual Station Productions. Not all stations depend on the Cooperative to get their programs on the network. Stations will seek funding for a program or program series that they want to produce. A station will make a direct approach to a funding group and will ask that group to underwrite the cost of producing the program. Generally, only the larger stations have the resources to develop this type of funding since it requires a good deal of time in making personal contacts and writing program proposal grants.

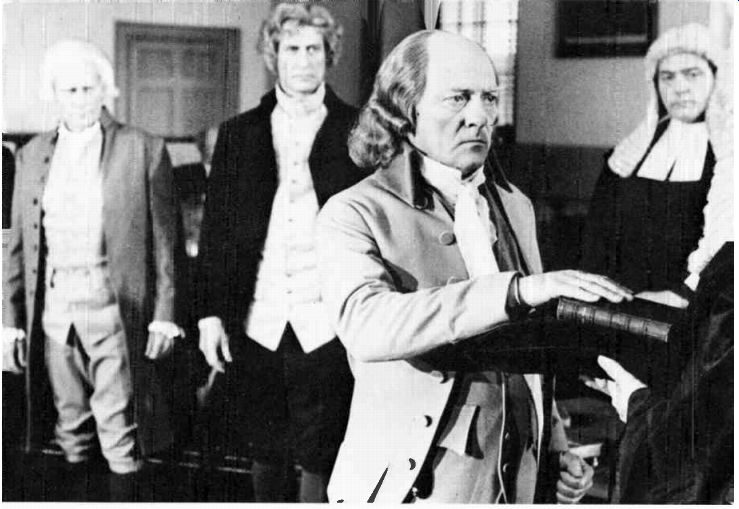

A program that exemplifies this kind of funding was "The Adams Chronicles," a series that was first run in the 1976 season. The program was produced by WNET in New York. Since the series was so expensive, $2 million dollars for 13 programs, the funding came from a variety of sources: the National Endowment for the Humanities (federal government), the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (private foundation), and the Atlantic-Richfield Company (business-industry). Since the production cost was funded by these sources, individual stations only had to pay the cost of having the program distributed to their station.

Outside Program Sources. Some programs are produced by organizations other than public broadcasting stations. The Children's Television Workshop (CTW), a nonprofit corporation, produced Sesame Street and "The Electric Company." Part of the program's costs are paid by CPB and the U.S. Office of Education. CTW also gets money by selling its programs abroad and by offering its name and characters to businesses that sell articles based on the programs.

------------ John Adams (George Grizzard) is sworn in as the

second President of the United States in the sixth section of The Adams

Chronicles, shown in 1976 over the Public Broadcasting Service. The

series of thirteen weekly one-hour programs tracing 150 years and four

generations in the lives of the Adams family was produced by WNET/13--New

York. (Photo by Carl Sam rock.)

The remainder of the production cost is picked up by individual stations, which pay for the program through the Station Program Cooperative. Since the program is partially subsidized by the government and by income generated by CTW, the cost to the individual station is lower than if it had to pay the total production cost.

PBS also has an underwriting office, the purpose of which is to persuade corporations and foundations to underwrite the cost of programs. Sometimes PBS is underwriting for already existing series that have been aired elsewhere.

An example of this is "Upstairs, Downstairs," which came from the British Broadcasting Corporation. In the case of this program, Mobil Oil was the underwriter.

Locally Produced Programs

Every public television station produces programs that are intended for local audiences and are not carried on the PBS interconnection. Many stations do a great deal of programming in the area of public affairs. These programs typically deal with problems of their local communities. Most stations also devote programming time to local cultural activities such as dance, art, and music. Depending on the station's money and resources, the programs range from talk shows, in which participants sit and discuss community problems and activities, to documentaries or the actual filming of local events.

Stations that are run or supported by educational organizations and institutions often produce instructional programming designed for classroom use.

When school is in session, public television stations devote an average of 30 percent of their total broadcast hours to classroom programming. Some of this programming is locally produced, while some of it comes from regional or national sources.

Regional Networks

There are several regional educational networks in the United States. The Eastern states, for example, are covered by a network called the Eastern Educational Television Network. Stations that are in the states covered by these networks acquire programs collectively, with each station paying a portion of the cost. Individual stations within the network range also produce pro grams that are shown on the regional network.

Some states also have networks and, as with the regional networks, the stations in the state will produce or purchase programs intended for use within the state.

Other Program Sources

There are hundreds of organizations that produce programs that public broadcasting stations can rent or show for free. Many of the programs that are available for commercial stations are also available to public television stations--the difference being that public television stations cannot insert commercials. In addition to the commercial sources, public television stations also use organizations that produce educational programming. There are many program choices, ranging from the types of films that are shown in classrooms to programs that are produced specifically for instructional television use.

National Public Radio

Unlike the public television network, National Public Radio produces a good deal of its own programming. In 1974 it supplied about forty hours of live programming a week to its member stations. As with the television network, member stations supply programming to public radio. Additionally, NPR gets programming from freelance producers.

Most of the funding for public radio comes from CPB and from sources generated by individual stations. There is also a certain amount of underwriting for programming but it is not as common as it is for public television. Some program underwriters, for radio have included Xerox, the Foreign Policy Association, and Psychology Today.

-------------

THE PUBLIC RADIO STATIONS --. In 1975 there were 177 public radio stations that covered about 60 percent of the United States. The audience for public radio is smaller than the audience for public television since there are no public radio stations in 34 of the 100 largest population areas.

In 1974 the average public radio station broadcast 121.7 hours weekly. Almost 65 percent of this was locally produced, 11 percent came from the interconnection, and the remainder came from other sources. Most of the local stations had music as their dominant programming. Of the total broadcast music hours programmed, classical music accounted for 61 percent. The next highest music category was jazz with 9.9 percent followed by several other conventional music formats.

The number of NPR stations is limited since stations must meet qualifications in staff, facilities, programming, power, and hours of operation before they become eligible for affiliation.

Source: CPB Report, December 21, 1975; CPB Report, February 16, 1976,

--------------

THE DIVERSITY OF PUBLIC BROADCAST PROGRAMMING

Throughout its short history, public broadcasting has offered great diversity and richness in programming. Programs such as Sesame Street, -Upstairs, Downstairs, and -The Adams Chronicles- are examples of programs that have both delighted and stimulated viewers.

Public television has also made it possible for viewers outside of major cities to see some of the great performers from cultural institutions such as the American Ballet Theatre and the Metropolitan Opera. Film lovers have been able to watch films by the major international film directors--an opportunity that is available in few American cities.

As well as offering a great variety of classical music programming, public radio has also been active in generating news and public affairs programming.

While most radio stations depend on the wire services for their news, NPR has often ventured into the area of investigative reporting and has often been the first news organization to discover important stories.

Although public broadcasting has been plagued by internal squabbles, inadequate funding, and governmental pressures, it has been able to present some of the most innovative programming in American broadcasting. For many people, public broadcasting often achieves broadcasting's great potential.

PROBLEMS FACING PUBLIC BROADCASTING

The single greatest problem that public broadcasters face is finding enough money to operate. Although public broadcasting does not have the commercial problem of attracting huge audiences for advertisers, the public broadcaster's preoccupation with money is just as intense as it is in the world of commercial broadcasting.

When public broadcasting first started it appeared that federal funding would solve a good many of its financial problems. In reality, however, the federal government pays only a small proportion of the total operating cost of public broadcasting.

The Public Broadcasting Financing Act of 1975 authorized funding for public broadcasting for the next five years. The Act provides a maximum of $88 million in 1976, which will increase to a maximum of $160 million in 1980. However, the Act does not guarantee that the maximum will be appropriated- the actual amount is ultimately determined by the House and Senate Appropriations Committee and it could be much lower than the maximum authorized funding. Further, the Act only provides funding on a matching basis; that is, public broadcasting must raise $2.50 from nonfederal sources in order to get $1.00 of federal funding. In other words, public broadcasting does not get any federal money unless it can produce nonfederal dollars at a 2.5:1 ration. 12 This type of funding places a good deal of responsibility both on PBS and on the individual station. PBS must search for program underwriters while local stations must continue to cultivate underwriters, state and local government, and audience support. Unless the public broadcasting system concentrates on funding by aggressively seeking funding sources it will be in serious trouble.

As well as facing economic problems, public broadcasting is also vulnerable to political pressures. Politics and economics are closely related, for those who pay the bills are likely to call for specific programming politics. During the Nixon administration there was strong feeling against the federal government's support of public affairs programming-particularly when it was unfavorable to the Administration. In order for public broadcasting to get its annual appropriation it had to "reform" by presenting fewer hours of both controversial and non controversial public affairs programming. Congress has also influenced programming by granting funding on an annual basis. Public broadcasters have believed that if they presented programming that was "acceptable" to Congress, Congress would reward them with increased yearly appropriations.

State governments have also used their influence. Any number of governors and state legislators have made strong recommendations about what their stations should program.

Public broadcasters have long argued for long-range federal funding-a system by which public broadcasting would be funded for several years rather than on a year-to-year basis. The broadcasters argue that long-range funding would enable them to engage in long-term planning and that long-range funding would make the system less vulnerable to yearly political pressures. The Public Broadcasting Financing Act of 1975 provided such funding for the first time. The Act authorized the system to be funded for the 1976, 1977, and 1978 seasons. Although it is still too early to tell what the impact of this funding might be, it is possible that programming might be less vulnerable to federal government pressure because of this Act.

The public broadcast system does not have to remain poor; numerous people and organizations have come up with creative ideas for means of sup port. The Carnegie Commission recommended that the system be supported by an excise tax. Under this system everyone would pay a yearly excise tax on their radio and television sets (much in the same way that one pays for the license plate on a car) and this money would be used to support the public broadcast system. Others have suggested that since business and industry al ready underwrite program costs it is hypocritical to call the system noncommercial. These people recommend that public broadcasting carry commercials, but only at the end of programs and with the stipulation that advertisers could not sponsor specific programs-they could only buy time.

Both of these systems of support have been used successfully to support European systems of broadcasting. Why, then, have they never been seriously considered as a form of support for American public broadcasting? Although the answer to this question is not clear cut, we can offer some speculative answers.

Basically we believe that it is in the interest of both Congress and commercial broadcasters to keep the public broadcasting system poor. As we have already pointed out, if the system is dependent on Congress for a portion of its funding, the system is likely to come up with programming that will be acceptable to Congress. If the system were largely self-sufficient, it would be free to program as it wished.

As far as the commercial broadcasters are concerned, they do not want a fourth network that would compete either for audience or for advertising dollars. As long as public broadcasting offers programming that only reaches a few million people it does not provide any real competition for commercial broadcasters. Therefore, it is in the interest of commercial broadcasters to op pose additional funding. If it appears that public broadcasting might become too powerful, we suspect that commercial broadcasters would be the first to protest.

Although the public broadcasting system has only existed since 1967, it is al ready locked into a system that resists reform or change. Public broadcasting is not likely to disappear--it is too firmly established. Its future economic health, however, will depend on how well it can appease various political and economic sources that supply its funding.

NOTES:

1. S. Young Lee and Ronald J. Pedone, Status Report on Public Broadcasting (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975) p. 7.

2. Edwin G. Krasnow and Lawrence D. Longley, The Polities of Broadcast Regulation (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1973), p. 86.

3. Erik Barnouw, The Golden Web (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968), p. 294.

4. Lee and Pedone, p. 11.

5. Lee and Pedone, pp. 14, 16.

6. Lee and Pedone, p. 17.

7. Communications Act of 1934, Section 399.

8. Lee and Pedone, pp. 22, 26.

9. Lee and Pedone, p. 15.

10. CPB Report, December 15, 1975.

11. CPB Report, December 15, 1975.

12. CPB Report, February 16, 1976.