In preparation for a recent television season, CBS contracted for one of the most lavish and expensive television series of all time, " Beacon Hill." The new series, unabashedly modeled after the popular BBC series "Upstairs, Downstairs," was the fictional story of the Lassiter's, a wealthy family living in Boston during the 1920s. CBS spared no expense in producing the series: extensive research was conducted to guide the re-creation of the 1920s settings, some of Broadway's best actors and actresses were hired to play the roles, and the program was shot in a variety of exterior and interior settings. As one net work executive put it, " Beacon Hill" was "the Tiffany of TV series." Even though CBS lavished money and attention on the series, it also risked a great deal by producing the program, for "Beacon Hill" was decidedly un characteristic of the typical television programming of police adventure and situation comedy. CBS could, however, afford to take this risk because for the past nineteen television seasons it had been the number one network in national ratings--meaning that it attracted more viewers than any other network.

Even though CBS was number one, it was still concerned about "Beacon Hill's" ability to attract a large enough audience to keep the series going. The network developed several strategies: more money was used to promote the series than for any other program, the series was premiered a week earlier than its competitors, and the premiere was scheduled opposite the low-rated NBC baseball night.

After the premiere it looked as though the strategy had been successful, for according to the Nielsen ratings, the premiere program attracted a sizeable audience. By the second week the series' ratings were down, and in the third week the program was in third place--far behind ABC and NBC programs.

During the fourth week the program increased its ratings a little and the producers and network executives were a little more hopeful. By the fifth week, however, catastrophe struck: not only was " Beacon Hill" in third place--so was CBS! When CBS again appeared in third place for the sixth week, it was clear that there was no time left for sentiment. CBS had to drop all of the poorly rated programs, and clearly - Beacon Hill" was one of those that had to go.

After the demise of "Beacon Hill" there was speculation about what went wrong. NBC claimed it had always known that the series would never attract audiences. The producer and the writer of "Beacon Hill" blamed each other and some industry personnel and television critics blamed the American viewer for not having enough taste to appreciate the program. The failure of -Beacon Hill- illustrates the nature of the American commercial television business. The series disappeared, as have countless other series, because it could not attract a large enough audience. Audience size is measured by the rating services, and since programs succeed or fail on the basis of their ratings, understanding the rating system is an essential element in understanding American broadcasting.

THE REASONS FOR RATINGS

When advertisers decide to commit thousands of dollars to buying broadcast time for the commercials, the first question they are likely to ask is "who is watching or listening to the show or the station?" Answers to this question are provided by the rating services-companies that are set up to measure audience size and composition. Advertisers, stations, and networks subscribe to the rating service's and make advertising and programming choices based on the data they receive.

Since broadcasters depend on advertising revenues for their support, ratings are essential to their economic survival. If the number of potential consumers for a particular program is not satisfactory, the advertiser will switch support to another network or station.

Ratings also work in favor of a station or network. Since advertisers prefer to have their commercials appear on the highest-rated programs, the stations with the best ratings will usually get the best prices for the sale of broadcast time.

Thus, broadcasters use ratings to "sell" their stations and networks to advertising clients.

The ratings not only offer information about audience size, but they also provide information about audience composition-called demographics, or "demos." This demographic data, which typically gives information about the age and sex of the viewers, is crucial to the advertisers so that they can identify the target audiences for their products. For example, demographics (and common sense) tell the advertiser that the audience for Saturday morning cartoons is predominantly children. Since children are a logical target audience for products such as toys or chewing gum, manufacturers of these products buy Saturday morning time to advertise.

Thus, we can see that as well as providing information about audience size and composition, the ratings services tell the stations and networks how well their programs are doing in attracting the right kinds of audiences. Since this information is only available through the rating services, these services are vital to the economic well-being of the commercial broadcast industry.

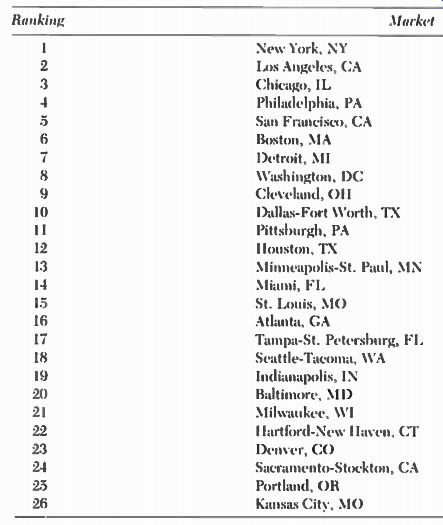

TABLE 7-1 The Top 50 Television Markets, as Ranked by the American Research

Bureau.

Source: Broadcasting Yearbook 1977. (Washington, D.C.: Broadcasting Publications Inc., 1977). pp. B80-81.

CONDUCTING RATINGS RESEARCH

Market Areas

If all broadcast advertising and programming was intended for a national audience, the rating services' problems of measuring audience size andcom position would be greatly reduced. Because much advertising is spot or local, however, and since no station has a signal that reaches the entire country, the rating services must also provide audience information about specific areas of the country.

In order to provide information about local, regional, and national audiences, the rating services have divided the entire country into market areas, that is, areas that are reached by radio and television signals. They have done this by taking all of the 3,141 counties in the United States and grouping them into 209 market areas. Where the population is dense, such as in the New York area, there will be only a few counties in the market area; where the population is sparse, the market area will contain many counties. Each county, however, is assigned to only one market area.

Two rating services, Arbitron and Nielsen, originated this system of defining market areas according to counties. Arbitron's market areas, the most widely used by the industry, are called "areas of dominant influence" (AM). Nielsen's are called "designated market areas" (DMA). Both Nielsen and Arbitron assign rankings to the designated market areas.

The markets that are ranked highest are those which have the greatest number of households with working television sets. In Table 7-1, Arbitron identifies the top five markets as being New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, and San Francisco.

The market area information provided by the rating services is important because the larger the market area, the greater the potential audience for the advertising message. Thus the number-one market, New York City, has far greater audience potential than the Albany-Schenectady-Troy market, which is ranked number forty-two. An advertiser who reaches the top ten markets will reach a substantial portion of the United States population. Therefore, advertising time is more expensive in major markets than it is in medium or small markets.

Coverage and Circulation

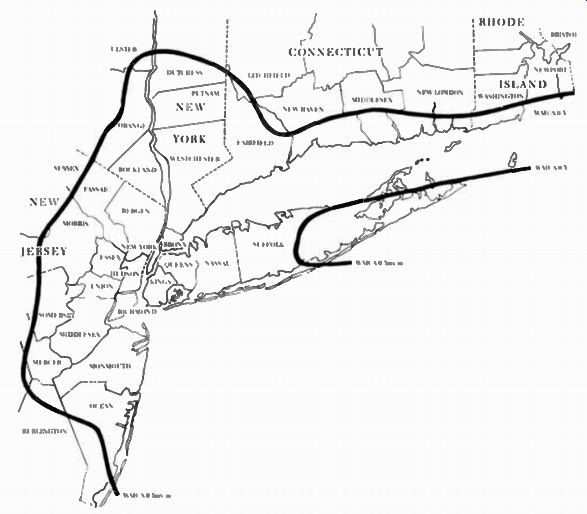

Figure 7-1. Radio coverage map of New York.

(WMCA).

Advertisers not only need information about the potential audience in market areas, but also information about how much of the market area a given station can reach. For example, a low-powered station in a market area that contains many counties might only reach a small percentage of that market area's viewers or listeners. Therefore, when advertisers decide to buy broadcast time they must consider stations in terms of their coverage and circulation. Coverage refers to the station's signal and how much geographical area it can reach. This is generally determined by the strength of the signal and the contours of the land. Figure 7-1 shows the coverage area of radio station WMCA in New York.

Circulation is the term used to refer to the station's potential audience for programming; if at least 5 percent of an audience within a particular county tunes into the station at least once a week, that county is considered to be part of the station's circulation area.

Networks need to know the coverage and circulation of their affiliates, and such information is also essential to individual radio and television stations.

Before advertisers buy broadcast time, they want to know the geographical boundaries of a station's audience. However, both coverage and circulation are only indicators of a station's potential audience. Even if a station can reach an audience, there is no assurance that the audience will want to listen to or watch the station. The question of how many people are actually in the audience can best be answered by the rating services.

The Measurement of Audiences The United States has approximately 68.5 million homes with television sets.

To discover what every household is watching on television would obviously be an overwhelming task; by the time the job was completed the information would be history. In order to facilitate the rating process then, the rating services take a sample, or small segment, of the population, monitor its viewing choices and then generalize about the viewing habits of the entire population on the basis of what was learned from the sample.

Sampling is a well tested and well accepted research technique among natural and social scientists. If you are going to have your blood tested, for example, you know that it is not necessary to drain your whole body-a sample will suffice, for what is true of that sample is very likely true of all the blood in your body.

The rating services, then, apply this sampling principle. They do not test the entire population, but instead test a sample of the population. It should be emphasized, however, that this sample is not chosen haphazardly. The samples the rating services use are designed to accurately represent the entire United States population, and every member of this population has an equal chance to be chosen as part of the sample. Further, the sample is broken down into segments. For example, if 10 percent of the entire United States population earns over $15,000 a year, then 10 percent of the sample should earn over $15,000 a year. This technique of matching the sample to the population is called stratification. Different rating services may stratify their samples in different ways, but usually the sample reflects differences in income, age, race, sex, and geographical area.

Because the rating services use stratification in choosing their samples, they automatically have the demographic information that is so important to advertisers. This demographic information in turn provides information about CPM (see page 154). For example, if the rating services discover that the audience for an afternoon soap opera is predominantly adult women, advertisers who wish to reach such an audience will be guided by that information when they make decisions about which time slots to buy for their messages.

Thus sample stratification provides demographic information about audience composition, which in turn enables advertisers to figure CPM for the variety of audiences that are reached by the broadcasters.

Data Gathering Techniques

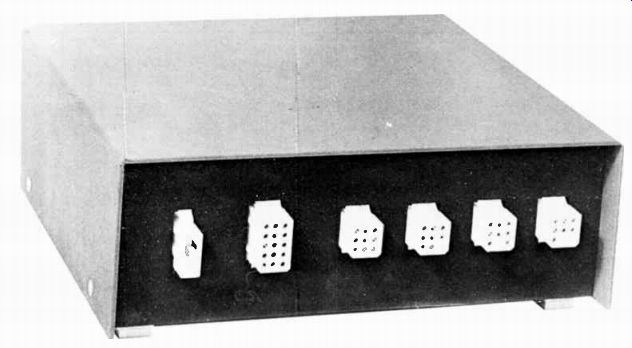

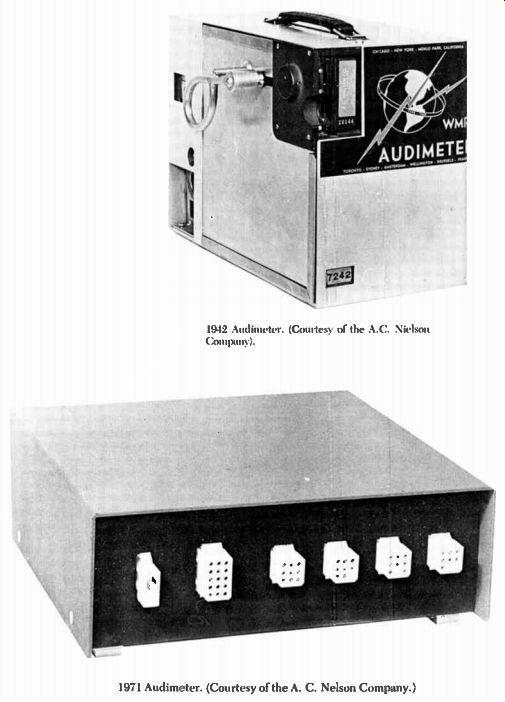

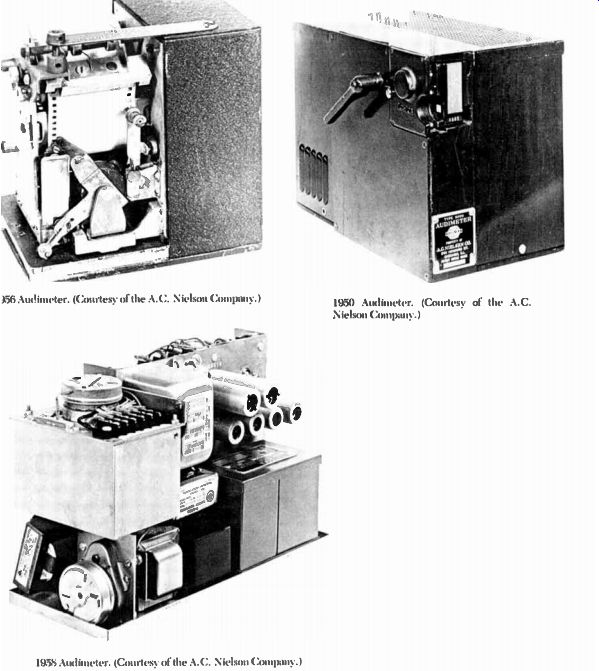

After the rating services have selected their sample households, they use a variety of techniques to discover what these households listen to or watch on radio and television. The techniques most commonly used are as follows: Electronic Monitoring. The most influential television ratings are provided by the A. C. Nielsen Company, which gathers its information by electronically monitoring all the television sets in its sample homes. A device known as the Storage Instantaneous Audimeter, or SIA (commonly referred to simply as the Audimeter), is installed by Nielsen representatives in approximately 1,160 households across the United States. The Audimeter is wired directly to the household's television sets and is able to record when each set is turned on and what channel it is tuned to (see Figure 7-2). The Audimeter monitors the sets continuously, at 30-second intervals, which means that it can keep very ac curate track of channel switchings. Each Audimeter is linked, by means of a separate telephone line, to Nielsen's main computer center in Dunedin, Florida. At least twice a day a "collecting" computer dials each home unit and gathers the information stored by the Audimeter. The collected information is then transferred to a "processing" computer, which organizes the data and generates the many reports that Nielsen issues.

Nielsen offers a wide variety of ratings reports to its subscribers, who choose from the range of reports according to their individual needs for in formation. The subscriber services offered by Nielsen fall into two basic categories: reports that provide information on a national basis, and reports that provide information on a local basis. Nielsen calls its national service the Nielsen Television Index (NTI) and its local service the Nielsen Station Index (NSI). Table 7-2 describes briefly the main ratings report services available from Neilsen.

-----------------------

WMCA RATE CARD #45

Effective November 15,1976

CHECK STATION FOR GRID NUMBER IN EFFECT-HIGHER GRID PREEMPTS LOWER. 10-second spots 50% of minute rate.

Figure 7-2. Sample rate card. (WMCA.)

--------------------------

--------------- Audimeter. (Courtesy of the A.C. Nielson

Company.)

The main strength of the Audimeter system is that it allows Nielsen to report data faster than any other rating service. Before Nielsen engineers developed the latest model Audimeter, it took one to two months to compile the ratings data. Now Nielsen can report data within a time period that ranges from overnight to one or two weeks.

On the other hand, the Audimeter system also has weaknesses. One problem stressed by critics of the system-and acknowledged by Nielsen it self-is that although the Audimeter records the times when the set is in use and the channels it is tuned to, the instrument has no way of determining whether anyone is actually watching the set. Television sets are often turned on to provide background noise while members of the household are busy with...

---------------

TABLE 7-2 Nielsen Ratings Services Local Services

Overnights. Available only in the three largest markets ( New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago), these reports are issued by 10:00 AM each morning, with ratings data on the previous day's programming in those markets. Even though the overnights only cover three markets, many network executives look at them as an indication of national program preferences.

Multi-Network Area Reports (MNAs)

These reports, available one week after a viewing date, provide information about the total audience, the number of stations carrying a program, and the percentage of coverage of the nation. The MNA ratings apply to the seventy largest population centers in the United States.

National Services SIAs, or Dailies. SIA reports are issued 36 hours after a viewing day and contain in formation on program ratings and share of audience.

National Television Index Reports (NTIs). NTIs are comprehensive reports issued at two-week intervals and covering two weeks of programming. They contain information about average audience, number of households using television (HUT), share of audience, as well as demographic information about audience composition.

---------------------------

...activities other than viewing. When the television set is left on, the Audimeter reports the set in use, even if the household cat is the only viewer.

Critics of Nielsen's system also complain that not enough care is taken to maintain the demographic mix of the sample. They claim that when the members of a sample household move away, Nielsen is sometimes reluctant to remove its Audimeter promptly. This means that the sample gets distorted if the new occupants of the house do not have the same demographic characteristics as the original occupants. For example, if the sample household was originally made up of a young married couple with two children and they are re placed by a middle-aged couple with no children, the demographic characteristics of that household are significantly changed. If Nielsen sticks with the second couple instead of finding another family similar to the one that moved away, the sample becomes less representative of the United States population.

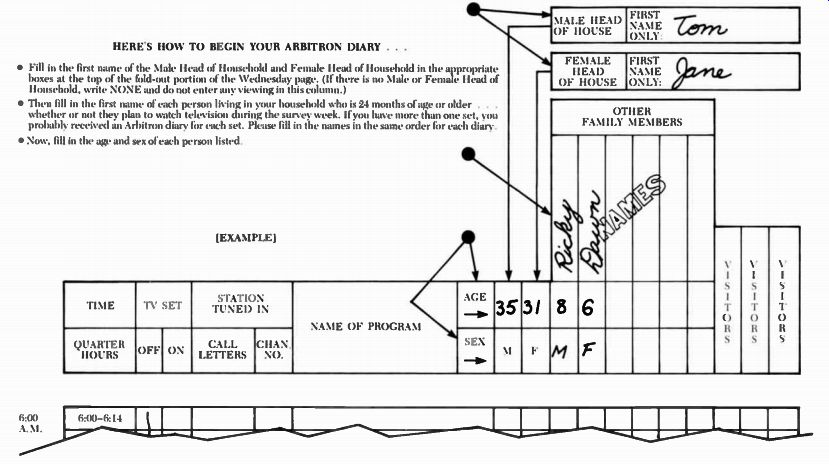

Diaries. Two of the rating services, Arbitron and Nielsen, use diaries to obtain viewer and listener information. Respondents are asked to make entries in the diary listing the times they spent viewing, the channel numbers they were ...

--------------------------

SWEEP WEEKS AND BLACK WEEKS

Since a good rating is so essential to a station's economic well-being, stations are tempted to try to increase their ratings by a process called "hypoing." Although the blatant forms of hypoing such as contests, give-aways, and promotion stunts during rating weeks are discouraged by the FTC, the FCC, BRC, and the rating services, the more subtle forms are harder to control.

One example of hypoing occurs during sweep weeks-the three weeks out of the year that Arbitron and Nielsen "sweep" the country to measure the audiences of the network affiliates. During these weeks the networks provide special programs on nights that have been doing poorly in the program schedule. This special programming offers popular performers, recent hit movies, and so on. If this special programming is successful, the affiliates will be able to gather bigger audiences and thus charge a higher price for advertising time.

Although the sweep weeks may glitter, the networks offset them with black weeks. Black weeks are the four weeks a year when Nielsen doesn't do ratings-therefore a low rating during those weeks won't hurt anyone. If you see a number of cultural and documentary programs all within a single week, you can be pretty certain that it's a black week.

Source: Les Brown, "TV Notes: How 'Sweep Weeks' Hype the Ratings,"

... New York Times, December 7, 1975, p. D 37.

-------------------------

------- 1942 Audimeter. (Courtesy of the A.C. Nielson Company).

1971 Audimeter. (Courtesy of the A. C. Nelson Company.) 1956 Audimeter.

(Courtesy of the A.C. Nielson Company.) 1958 Audimeter. (Courtesy of

the A.C. Nielson Company.) 1950 Audiometer. (Courtesy of the A.C. Nielson

Company.)

----------------

... tuned to, the stations' call letters, the names of the programs they watched, and the age and sex of the viewers. After completing the diary, the sample household mails it back to the rating service, which analyzes and reports the data to its subscribers. Figure 7-3 shows a page from an Arbitron diary.

Arbitron uses counties as sample units and chooses its respondents from within the county by using a computer to randomly select telephone numbers of county residents to be contacted for participation in the survey. The size of the sample will range from 300 to 2,400 households, depending on the size of the market where the research is being conducted.

Nielsen uses the diary system to supplement its Audimeter system. In addition to the approximately 1,160 households that it monitors by means of the Audimeter, Nielsen also has roughly 2,300 households that keep diaries.

Nielsen calls its diaries Audilogs. Households that participate in Nielsen's Audilog system fill out their diaries for the third week of every month from September to February, as well as for other selected periods during the year.

Generally, a Nielsen household will keep a diary for a total of eleven or twelve weeks each year. Nielsen also uses diaries for Sweep weeks.

The Nielsen Audilog diary system also employs an electronic device known as a Recordimeter, which is attached to the television set to record the amount of time the set is in use. An additional function of the Recordimeter is to emit an audible signal every thirty minutes that the set is in use to remind viewers to make entries in their Audilog diaries. Nielsen compares the record of set use provided by the Recordimeter to the Audilog entries as a check of the diary keeper's accuracy.

The main advantage of diary sampling is that it can measure actual viewing and can provide valuable information about the composition of the audience.

The main disadvantage of diaries is that they are subject to human error.

Respondents often misunderstand the instructions, fill their diaries in improperly, mail them in too late to be counted, or forget to mail them at all.

Telephone Interviews. Rating services generally use two types of telephone interviews, coincidental and recall. In a coincidental interview, the interviewer asks the respondent what she or he is watching or listening to at the time of the interview. In a recall interview, the interviewer asks the respondent about use of broadcast media for the past day or so. Sometimes telephone interviewers use aided recall techniques where they read off a list of what was on radio or television or the call letters for the stations in the area. Aided recall helps respondents to remember details about their recent viewing or listening that they may have forgotten. Telephone interviewers will often ask the sex and age of the respondent, as well as information about those who were present when the viewing or listening took place.

----------------------------

Figure 7-3. Source: Arbitron Television, American Research Bureau, 1350

Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10019.

HERE'S HOW TO BEGIN YOUR ARBITRON DIARY

• Fill in the first name of the Male Head of Household and Female Head of Household in the appropriate boxes at the top of the fold-out portion of the Wednesday page. (If there is no Male or Female Head of Household, write NONE and do not enter any viewing in this column.)

• Then fill in the first name of each person living in your household who is 24 months of age or older . . .

whether or not they plan to watch television during the survey week. If you have more than one set, you probably received an Arbitron diary for each set. Please fill in the names in the same order for each diary.

• Now, fill in the age and sex of each person listed.

---------------------

TABLE 7-3 What Happened to the Original Sample in a Telephone Survey

-------------------

Telephone interviews are widely used by rating services and individual stations to gather rating information. Telephone interviewing systems have the advantages of measuring behavior as it is taking place, and of being inexpensive and easy. The disadvantage of using the telephone is that some people do not have telephones or their telephone is not listed. An even greater problem is that it is difficult to reach all of the people designated as part of the sample. Table 7-3, based on a Trendex survey in a metropolitan area, illustrates the types of problems telephone interviewers must face. The interviewers who con ducted that survey were able to complete just 59.2 percent of the interviews--even after call-backs.

Personal Interviews. One of the best ways to conduct rating research is through personal interviews. Pulse, which measures radio listening, uses this method. Pulse chooses its sample from telephone directories or census reports and then goes directly to the homes of its respondents. Depending on the population size of the area surveyed, Pulse will interview anywhere from 500 to 2500 respondents.

Pulse personal interviewers use aided recall techniques. Since radio does not have clearly defined shows, Pulse asks questions about time periods.

Respondents identify which stations they listened to the previous day, from the time they woke up until the time they went to bed. Respondents are also asked to tell which stations they listened to during the previous week. In all cases, Pulse asks for specific listening information rather than for general listening preferences. Pulse reports station listenership data by age, sex, and the time of day respondents listen.

Personal interviews are the best way to get a good response from the persons in the sample. The disadvantage of personal interviewing is that it is expensive; the rating service must hire and train interviewers, and the inter viewing itself takes a good deal of time-especially in areas that are sparsely populated or in areas where people are often away from home.

Reporting Results

Once the rating service has selected a sample and has found a method of testing the sample, its next problem is to organize and report its results in a meaningful way. Although there are a variety of rating services, most of them make use of a common language in reporting their results.

The two measurements most commonly used are a program rating and a share of audience rating. A program rating represents the percentage of all the sample television households that are watching a specific program.

The most important ratings measurement, however, and the figure that most influences programming decisions, is called a share of audience rating or "share." To calculate a share of audience rating, it is necessary to first add up all the program ratings for all stations and networks for a given time period. The sum of all the program ratings for the time period is a figure that is referred to as a HUT ("households using television") rating, and it represents an estimate of the percentage of the total potential audience that was actually tuned in to the programs that were shown during that time period. Once the HUT rating for the time period is known, the share of audience rating for any program that was aired during the time period can be derived by calculating what percentage of the total viewing audience was tuned to that particular program. The share of audience rating thus provides an indication of how popular a program was in relation to the other programs that were aired at the same time. If a program gets a share of audience rating of 14, that means that 14 percent of the actual viewing audience watched the program, while 86 percent of the audience watched other programs in the same time slot. For a network prime time program to survive, it must usually get at least a 30 percent share. If it has a 40 percent share, it's a solid hit.

It is possible to have a seemingly high numerical rating and a mediocre share of audience and vice versa. During prime time, for example, a program may reach 15 million television households. This may represent a high rating, but if the program's competitors are reaching three-quarters of the audience with their sets tuned, the program's share of audience is not very good.

Conversely, during late-night programming a show might only reach two million people, which would represent a low rating. But if those two million people represent two-thirds of the actual viewing audience for that time period, the program has won a sizable share of the audience. From the national advertisers point of view, the ideal situation would be one in which every set in the entire United States was tuned to the program that they were sponsoring.

This would mean a 100 rating and a 100 percent share. Since this never hap pens, advertisers must be content with sponsoring programs with large audiences or, more importantly, programs with the largest share of viewers or listeners.

Both ratings and shares are computed on a national and local basis. The net works and national advertisers are interested in national figures, whereas local stations are often more concerned with ratings in their particular coverage areas.

Program ratings are also refined by measuring them under three different circumstances: instantaneous, average, and cumulative ratings. An instantaneous rating is taken during a particular time period during a program. For example, an instantaneous rating could tell you the percentage of your sample that is watching "All in the Family- at 9:07 P. M. An average rating gives the average percentage of the audience watching over a time period. In the case of "All in the Family- an average could be calculated over a fifteen minute period or over the entire thirty minutes that the program is on the air. A cumulative rating (often called a cume) gives the percentage of the audience that was watching over two or more time periods; we might want to know, for example, the cume for "All in the Family- for a four or five week period. The rating one finds most useful will depend on the program being broadcast. The audience for a documentary that is broadcast only once would have its rating figured on an instantaneous or average basis; a cumulative rating would be more useful for a continuing series.

NETWORK AND STATION REPONSE TO RATINGS

Television Scheduling Strategies

As we have seen, good ratings are essential if networks and radio and television stations are going to survive. Since the dollar stakes are the highest at the net work level, the networks have evolved a variety of scheduling strategies intended to improve their ratings.

A common strategy is counter programming, whereby a network puts its most popular program opposite a popular program on another network in the hope of taking the competitor's audience away. Another counter programming strategy is to put a different type of program in competition with opposition programming. For example, NBC might program a variety show opposite ABC and CBS situation comedies in the hope that the variety show would attract an audience that did not like comedies. Also, networks often put low-rated pro grams such documentaries opposite each other. The philosophy behind this move is that it is better to do poorly together-in that way no one is the loser.

Networks often run similar programs back to back during a particular time period in order to keep the same audience. This strategy, called block programming, is designed to produce a good audience "flow- from one program to another. Typical examples of block programming are an afternoon of soap operas or an evening of police adventure programs. A similar programming technique is strip programming, whereby a network or station runs the same programs at the same time every day. Soap operas and evening newscasts are examples of strip programming. This strategy appeals to viewers' loyalties and habits; if you watched it on Tuesday you will probably watch it on Wednesday too.

A network never looks at a program as an isolated entity; an individual program is always considered part of the overall schedule and must be placed on the schedule in a way that will enhance both itself and the surrounding programming. One network strategy is to move a strong program to a time period in which the program schedule is weak, in the hope that the strong program will strengthen the schedule. "All in the Family" has moved five times in six years-always taking the audience with it and thus improving the schedule on the night on which the program appears. This strategy does not al ways work, however. "M*A*S*H," a very strong program, almost failed when CBS moved it from Tuesday to Friday night in the 1975-76 season. Once CBS moved it back to Tuesday, it regained its rating strength. A new program's rating potential is often enhanced when it is scheduled between two highly rated programs-a practice known in the industry as "hammock-ing." Every viewer at one time or another is the victim of timing strategies. For instance, a network may begin an hour-long program at 8:30, hoping to get you so involved that you will not think of switching to the other networks for their 9:00 programs. The winner at this game is the network that can keep the same audience for the entire evening.

Programming

Besides influencing the scheduling of the networks, ratings also have a strong influence on the kinds of programming the networks offer. Since ratings indicate which shows are popular and which are unpopular, the network programmers try to use ratings to make predictions about the kinds of programming that are likely to be successful. They know, for example, that public affairs and cultural programming attracts small audiences and few advertisers and so they provide very little programming of that kind.

Determining the ingredients of successful programming is more difficult.

Since no one is very certain what kind of rating an innovative program will at tract, the programmers try to limit their risks by providing new programs that resemble past successes. If a police adventure show works well in one season, there will be similar shows in the future. If a series has several strong characters, the programmers may take some of the characters away from the original series and create a new series around them--shows created according to this strategy are known as spin-offs.

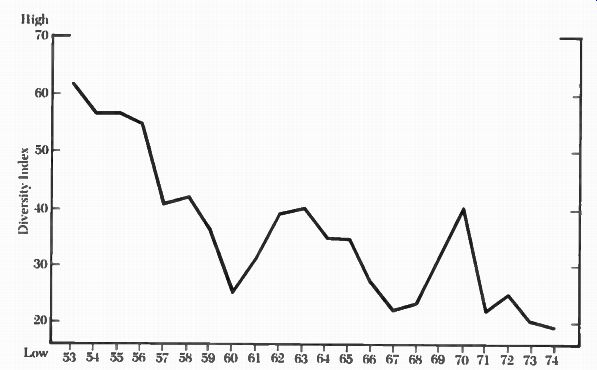

Figure 7- 4 gives a summary of prime-time programming diversity from 1953 to 1974. As the figure shows, although there was a good deal of diversity in 1953, diversity began to decline steadily from that point on, reaching its lowest point in 1974. At that time, 81 percent of all prime time programming fell into one of three program categories: action/adventure, movies, and general drama. 3 Although this study ends in 1974, there is no reason to believe that programming is becoming any more diverse.

Programming may also change because the rating demographics are wrong for the advertisers. ”Gunsmoke" was cancelled after twenty years, even though at the time of cancellation it was still one of the top twenty-five programs, with an audience of about 36 million. A CBS vice-president explained that it was cancelled because -the show tended to appeal to rural audiences and older people. Unfortunately, they're not primarily the ones you sell to. Gunsmoke is not the only show to have suffered this fate. All three networks have dropped a number of shows because they were not appealing to the right kind of audience.

Programming has also been influenced by the new rating service technology. The 1974-75 television season was the first season to make full use of Nielsen's improved Audimeter, the Storage Instantaneous Audimeter. Prior to that season, Nielsen used Audimeter instruments that recorded viewing data on film. Since the film had to be mailed back to Nielsen, it was a much slower procedure than the present one. The new system has meant that networks and advertisers are able to make much quicker decisions about programming choices. Although network executives buy 13 weeks of a program at a time, they have shown no reluctance to drop a program that earns a poor rating, sometimes after only one or two shows have been aired.

---------- Figure 7-4. Diversity in network prime-time schedules,

1953-74. Source: Joseph R. Dominick and Millard C. Pearce, "Trends

in Network Prime-Time Programming, 1953-1974," Journal of Communication,

Vol. 26, No. 1 (Winter 1976), p. 77.

------------

Radio Ratings

Ratings are as important to radio as they are to television. In a medium market, stations compete to be the number-one rated station. In a major market, ratings also distinguish between stations with similar formats. For example, in a

market with two or three Top-40 stations, ratings will tell which of these stations has the largest audience. There have also been cases where stations with consistently low ratings will change their formats in the hope that their ratings will improve.

The most important rating time for most AM stations is drive time. Most stations will make an effort to make the programming in this time period as appealing as possible.

MONITORING THE RATING SERVICES

Although audience measurement has existed since the early days of broadcasting the question of audience size became critical when stations began to increase in numbers and advertising time became more and more expensive.

Advertisers were not interested in "hit-or-miss" advertising. They wanted assurance that their messages were reaching enough of the right kind of people.

Only rating services were equipped to provide this audience information.

Although many of them had existed for years, their role in the broadcast industry gradually became essential rather than peripheral. However, it became clear that some rating services were not doing a very good job when in 1962 the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) ordered three of them to stop misrepresenting the accuracy and reliability of their figures. The FTC order was followed by a Congressional investigation of the rating services in 1963. The investigation revealed that the rating services sometimes doctored data, were careless, and engaged in outright deception.

--------------

THE MOST VALUABLE PLAYER IN BROADCASTING

Network executives who work out successful programming strategies are well rewarded for their efforts. In 1975, Fred Silverman, who was responsible for the CBS 1974-75 program schedule, left CBS to go to ABC. Industry sources said that ABC gave him a three-year contract at $250,000 a year, $1 million-worth stock, $750,000 in life insurance, and apartments in both Los Angeles and New York City. Within a week of the announcement of his move to ABC, ABC stock increased in value by a total of $85 million. For ABC, the hiring of Silverman paid off, in the 1976-77 season, ABC held the first place in ratings for the first time in its history.

Source: Jeff Greenfield, "The Fight for $60,000 a Half Minute," New York Magazine, September 7, 1975, p. 75.

---------------------

The Broadcast Rating Council

Probably in response to the fear of government regulation, the industry decided to set its own house in order. In 1964, the National Association of Broadcasters established the Broadcast Rating Council (BRC) and made it responsible for setting standards for the rating services and accrediting and auditing them. In order to get BRC accreditation, a rating service must disclose its methodology and procedures to the council. The BRC also conducts a periodic audit of the accredited services to make certain that they are following the methodologies they have described. Arbitron, Nielsen, and Pulse, as well as two smaller services, are currently accredited by the BRC. The Committee on Nationwide Television Audience Measurements The second response of the industry to the government's investigation of rating services was to set up its own research committee to investigate the methods used by the rating services. Formed by the NAB and the three television net works, this group was known as the Committee on Nationwide Television Audience Measurements (CONTAM). CONTAM's job was to answer some of the questions that were raised by the Congressional committee. The first question was whether measurements based on a small random sample of the national television audience could accurately reflect the viewing behavior of the audience as a whole. By drawing and measuring its own sample, and by comparing it to the rating service sample, CONTAM discovered that the sampling method used by the rating services was basically accurate. The second question CONTAM investigated was whether people who cooperated with rating services had different viewing habits than those who did not cooperate. CONTAM found that cooperators watched more television than non-cooperators, and thus rating service results were biased toward cooperator viewing habits. CONTAM therefore recommended that the rating services use better strategies to persuade people to cooperate. Finally, CONTAM compared the different rating services and found that, even when rating services used greatly different methods in measuring audiences, their results were very similar.

Basically the CONTAM study gave assurance that when rating services used methodologies that were well established in statistical theory they would get results that would give reasonable estimates of television's audiences. The All Radio Methodology Study The National Association of Broadcasters and the Radio Advertising Bureau also organized a study of radio methodology. The study, called the All Radio Methodology Study (ARMS), was initiated in 1963. The main objective of the study was to examine and compare the various methods of measuring radio audience, and the main conclusion of the research was that the coincidental telephone interviewing method was the most reliable.' As a result of the congressional hearing, the subsequent research studies, and the establishment of the Broadcast Rating Council, many of the methodological problems of the rating services have been solved. There are still problems, however, with those who subscribe to and use rating service data.

Since all of the rating services follow complex methods of gathering rating data, not all subscribers to the services understand the exact meaning of that data. It is important to keep in mind that ratings are estimates that are based on statistical theory. There is a built-in error of approximately three rating points on either side of the point estimate. This means that a program rating might be three points higher or three points lower than the rating that is actually reported. Because of this margin of error, one cannot necessarily assume that a program with a rating of 30 has more viewers or listeners than a program with a 28 rating, although managers of small stations have actually fired programming personnel on the basis of such a fallacious assumption. As well as being subject to statistical error, ratings are also subject to human error. These errors can range anywhere from a mistake in filling out a diary to erroneous data being entered into a computer.

Although rating services take the responsibility for their methods, they are quick to point out that they are not responsible for how their data is used--they insist that they are merely collectors of information. One might say that blaming the rating services for dropping a program is like blaming the mirror because you do not like your face-both the rating services and the mirror only reflect reality; they don't create it.

Most commercial broadcasters will agree that program quality, artistry, and creativity are all desirable but that the rating game is the only game in town.

Every fall season the network executives, program producers, and program talent anxiously await the latest ratings report. Those who are involved in the top fifteen shows can plan a cruise or buy a new house, while those in the bottom fifteen prepare for a long and hard winter. The poor folks in the middle range have the most anxious time of all, since their shows could go either way.

And we, the viewers, turn our dials and hope that something new and interesting will catch our attention. If it does, we hope it will survive or that the show we like will appeal to forty million Americans all between the ages of eighteen and forty-nine who will all go out and buy the sponsors' products.

With these ideal conditions, our favorite show could go on forever.

NOTES

1. Broadcasting (November 3, 1975), p. 40.

2. Broadcasting (September, October, November 1975).

3. Joseph R. Dominick and Millard C. Pearce, "Trends in Network Prime-Time Programming, 1953-1974," Journal of Communication. Vol. 26, No. 1 (Winter 1976), p. 77.

4. Jeff Greenfield, "The Fight for $60,000 for a Half Minute," New York Times Magazine (September 7, 1975), p. 62.

5. House of Representatives, Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, Broadcast Ratings, 1966.

6. Martin Mayer, How Good are Television Ratings? (New York: Television Information Office, 1966).

7. ARMS: What it Shows, How it has Changed Radio Measurement (Washington, D.C.: National Association of Broadcasters, 1966).