Men have advanced from myth-making to mathematical equation in search of

better ways of communicating their understanding of physical and social realities.

For centuries investigators were content to rely upon ordinary language as

a means of conceptualizing their hunches about reality. Not long ago the physical

scientists became disenchanted with words as a vehicle for thought and turned

to the language of mathematics; today, behavioral scientists reflect the same

dissatisfaction and search for more suitable symbol systems for coping with

their emerging problems.

The reason for this widespread discontent is not difficult to locate. Any hypothetical statement in sentence form must fit the categories of language and obey the rules of grammar. This is no handicap as long as the investigator deals with situations in which the elements are discrete and more or less constant, or where their influence upon each other is a linear or additive one.

-----------

by Dean C. Barnlund---From Johnnye Akin, Alvin Goldberg, Gail Myers, and Joseph Stewart, eds., Language Behavior: A Book of Readings ( The Hague, The Netherlands: Mouton and Co., n.v., Publishers, in press). Reproduced by permission of the authors and publisher.

----------------

Descriptive statements about such events can be a reliable way of postulating what is known, for language is a splendid instrument for handling stable elements and sequential or additive relationship.

There is serious doubt, however, whether or not the simplistic explanations demanded by language serve the ends of research sufficiently well if more dynamic forces and more complicated relationships are involved. This seems to be the case today. Both the problems that interest the behavioral scientist, as well as the perspective from which they are attacked, have changed radically. According to Peter Drucker there has been a quiet revolution in scientific thought during the past few decades. "An intelligent and well educated man of the first 'modern' generation-that of Newton, Hobbes, and Locke--might still have been able to understand and make himself understood up to World War II. But it is unlikely that he could still communicate with the world of today, only fifteen years later." The contemporary scientific world has quietly replaced the two related premises of the Cartesian, or mechanistic, view of the universe-that the whole is the sum of its parts and causality the only unifying order-with a world view that emphasizes process. This has brought about a theoretical revolution of such proportion that "virtually every one of our disciplines now relies on conceptions which are incompatible with the Cartesian axiom, and the world view we once derived from it." 2 Appeals for fresh approaches to the problems of matter, life and mind are no longer the exception in scientific journals. 3 One evidence of the changing perspective is seen in the new vocabulary of science. To convey their discoveries biologists resort to neologisms like ecology and homeostasis; psychologists analyze human personality in terms of drives and syndromes; rhetoricians find themselves talking about communication and meaning. All are terms that reject an atomistic or elementalistic approach in favor of a systemic or holistic one.

It is the whole of speech, including not only the words left unsaid but the whole atmosphere in which words are said and heard, that "communicates." One must not only know the whole of the "message," one must also he able to relate it to the pattern of behavior, personality, situation, and even culture with which it is surrounded. 4 Another sign of the search for new modes of attack on the problems of matter and mind can be found in experimentation with other modes of conceptualization. One of these innovations is the scientific model. As a theoretical tool the model is not an entirely unique instrument in that many theoretical statements can be translated into models, and some models, in turn, may be restated as theories. Yet, while admitting this, the scientific model remains one of the more promising ways of treating the complexities of human behavior and a method of representing its inner dynamics that deserves careful study.

---------------------

1. Peter F. Drucker, "The New Philosophy Comes to Life," Harper's Magazine (August, 1957), p. 36.

2. Ibid., p. 37.

3. See L. L. Whyte, Accent on Form (Harper, 1954) and J. F. T. Bugental, "Humanistic Psychology: A New Break-Through," American Psychologist (September, 1963). 1 Drucker, op. cit.

--------------------------

THE NATURE OF MODELS

A model is an attempt to recreate in physical or symbolic form the relationships alleged to exist among the objects or forces being investigated. It may consist of a complex arrangement of wires and relays built by a neurologist to reproduce the reflex loops of the nervous system, or an elaborate structure of sticks and wooden balls arranged by a chemist to duplicate the DNA molecule. Although models are as diverse as the questions men phrase in their search for knowledge, they can be classified broadly as to purpose and material.

Structural models are designed to show the formal properties of any event or object. They serve to identify the number, size and arrangement of the discrete parts of a system. A miniature solar system, charts indicating levels of management, diagrams of the components of an electronic computer illustrate the formal model. In other cases the model is designed to replicate function. The de signer attempts to represent the forces that comprise the system and establish the direction, volatility, and relation of their influence. Functionally isomorphic models need not resemble the event they simulate, but they must operate in essentially faithful ways. Walter's "tortoise" and Ashby's "homeostat" do not look like the cerebral cortex, but each duplicates some important function of the human brain.

Models also differ in the material of which they are made. Some are built of wood or steel or papier-mâché, and are constructed so that they can be manipulated or dismantled according to the whim of the investigator. Tangible models include prototypes of the human skeleton, replicas of assembly lines, clay mock ups of new pieces of equipment. Models may also be symbolic in character, consisting only of lines or shapes on a piece of paper. Lewin's vector drawings and Korzybski's structural differential are examples of symbolic models.

Our interest lies in the symbolic rather than physical model, and with the functional rather than structural model. It may become possible for future investigators to create mathematical models of human communication rivaling those of the physical scientists, but in the absence of sufficiently discrete variables and with current complications in measurement of these variables, this hope seems premature. The diagrammatic model seems best suited to accommodating our current level of knowledge about communication and, at the same time, providing an improved mode of conceptualizing over that secured through verbal statements alone.

VALUES AND LIMITATIONS

Several features of the diagrammatic model recommend it as a means of "picturing" the communication process. The complexity of communication has long been regarded as the major impediment to the study of human speech. Yet this obstacle may be unduly exaggerated, with much of the pessimism deriving from an outmoded strategy. When social scientists try to isolate and order all of the elements of a complex event-that is, when they approach such a system analytically-the results are often unmanageable. As Ashby has observed, "If we take such a system to pieces, we find we cannot reassemble it!" 5 The temptation, then, is to junk the whole idea and fall back upon over-simplified aphorisms and maxims. We may, as Grey Walter suggests, be able to do better than that.

The number of observed facts is the exponent of the number of possible hypotheses to relate them. When there are few facts and many impossible connections the subject may be understood without great difficulty, but when there are many facts from diverse sources and nothing can be assumed impossible special tactics must be used to permit an ordinary mind to see the wood rather than the trees. Perhaps the simplest and most agreeable device in such a situation is to construct models, on paper or on metal, in order to reproduce the main features of the system under observation. 6 One advantage of the model, then, is the ease with which it handles a multitude of variables and relates their effects upon each other in highly complicated ways, thus preserving the integrity of events under study.

To this must be added the heuristic or clarifying advantage of the model.

--------------------

5 W. Ross Ashby, "The Effects of Experiences on a Determinate Dynamic System," Behavioral Science (January, 1956), p. 36.

6. Grey Walter, "Theoretical Properties of Diffuse Projection Systems in Relation to Behavior and Consciousness," in E. H. Adrian (Ed.), Brain Mechanisms and Consciousness (Thomas, 1954), p. 367.

7 Considerable light is thrown upon communication theories of the past by making this sort of translation from text to model although a critical review of traditional theories of communication is beyond the limits of this paper.

----------------------

The designer of a model is forced to identify variables and relate them with a precision that is impossible for the writer to achieve because of the stylistic demands of effective writing. A diagram or formula can portray at a single glance, and with great transparency, the assumptions and properties of a new theoretical position, thus stimulating the study of alternative approaches. 7 Closely associated with the clarity of the symbolic model is its critical vulnerability. It simplifies the job of the critic who needs to identify innovation, who must discover the strengths, ambiguities and omissions of new conceptual positions. More models of human behavior might be produced if models were not so critically vulnerable, for even the architect cannot overlook the deficiencies of his own model. This, of course, is precisely what recommends it as a means of theoretical communication.

Not to be overlooked in these days of editorial compression is the compact nature of a model. Short of a mathematical equation, it is the most cryptic form in which a theoretical position can be communicated. While verbal description must supplement most models, once understood, the model is usually sufficient in itself to serve as a framework for empirical or experimental research.

Yet a model is no more than an analogy. As such it is subject to all the risks as well as opportunities latent in any comparison. Factors that appear in real life may be overlooked or distorted in the model. The relationships claimed may not parallel the dynamics of the observed event. The model may be oversimplified or over-elaborated; both errors can be contained within the same model. Some mod el-makers are carried away by what are essentially aesthetic, rather than empirical, considerations. And there is always the danger of becoming so entranced with the construction of models that the arduous search for new and irreconcilable data is neglected. In short, no model can rise above the empirical data and theoretical assumptions on which it rests. 8 The construction of any model proceeds in a circuitous way. One postulates what one can verbally, then translates these assumptions into diagrammatic form.

This, in turn, reveals omissions and distortions that must be eliminated by modifying assumptions, making further changes in the drawings, and so on. The following postulates, constituting the theoretical foundation of the proposed models can be derived from them, but it may be helpful to state them verbally and see to what extent they are realized within the diagrams that follow.

COMMUNICATION POSTULATES

COMMUNICATION DESCRIBES THE EVOLUTION OF MEANING. While we are born into and inhabit a world without meaning, we rapidly invest it with significance and order. That life becomes intelligible to us-full of beauty or ugliness, hope or despair-is because it is assigned that significance by the experiencing being. Sensations do not come to us all sorted and labeled, as if we were visitors in a vast but ordered museum. Each, instead, is his own curator. We learn to look with a selective eye, to classify, to assign significance.

----------------------------

8. See Alphonse Chapanis, "Men, Machines, and Models," American Psychologist (March, 1961).

9. Some of the material in this section is drawn from an earlier paper. See Dean C. Barnlund, "Toward a Meaning-Centered Philosophy of Communication," Journal of Communication (December, 1962).

----------------------------

The word "communication" stands for those acts in which meaning develops within human beings as neuro-motor responses are acquired or modified. It arises out of the need to reduce uncertainty, to act effectively, to defend or strengthen the ego. Its aim is to increase the number and consistency of meanings within the limits set by attitude and action patterns that have proven successful in the past, emerging needs and drives, and the demands of the physical and social setting of the moment. It is not a reaction to something, nor an interaction with something, but a transaction in which man invents and attributes meanings to realize his purposes.' " It should be stressed that meaning is some thing "invented," "assigned," "given," rather than something "received." The highly idiosyncratic character of our meanings is richly documented in studies of perception, particularly in the interpretation of projective tests. Flags, crowns, crosses and traffic signals do not contain meanings; they have meanings thrust upon them." Our physical and social environment, including the messages to which we attend, can be regarded only as placing some sort of upper limit upon the number and diversity of meanings we invent.

It is clear that communication, in this sense, occurs in a variety of settings traditionally neglected by students of communication. Meanings may be generated while a man stands alone on a mountain trail or sits in the privacy of his study speculating about some internal doubt. Meanings are invented also in countless social situations in which men talk with those who share or dispute their purposes. But no matter what the context, it is the production of meaning, rather than the production of messages that identifies communication.

COMMUNICATION IS DYNAMIC. The tendency to treat communication as a thing, a static entity, rather than a dynamic process occurring within the interpreter, seems to be an assumptive error of long standing and one that has seriously hampered the investigation of human communication. As Walter Coutu has stated so succinctly, "Since meaning is not an entity, it has no locus; it is some thing that occurs rather than exists. . . . Despite our Aristotelian thought forms, nothing in the universe 'has' meaning, but anything may become a stimulus to evoke meaning by way of inducing the percipient to give self instructions on how to behave in relation to it."

----------------------------------

10. The most recent writing on transactional psychology is found in Franklin Kilpatrick (Ed.), Explorations in Transactional Psychology (New York University Press, 1961).

11. This may explain why information theory which has so much to contribute to the study of message transmission has so little relevance for the study of meaning. The analysis of message "bits" neglects the semantic import of the message units which must be the target of the communicologist.

12. Walter Coutu, "An Operational Definition of Meaning," Quarterly Journal of Speech (February, 1962), p. 64.

13. Kenneth Boulding, The Image (University of Michigan Press, 1961), p. 18.

14. Whyte, op. cit., p. 120.

15. Susanne Langer, Philosophy in a New Key ( Mentor, 1942), p. 33.

------------------------------

Both entity and process are circumstantial, that is, contingent upon the surrounding milieu, but an entity is at the mercy of external conditions while a pro cess changes from moment to moment according to its own internal law or principle. The latter condition, according to Kenneth Boulding, clearly characterizes man as a communicator. "The accumulation of knowledge is not merely the difference between messages taken in and messages given out. It is not like a reservoir; it is rather an organization which grows through an active internal organizing principle much as the gene is a principle or entity organizing the growth of bodily structure." 13 This "internal organizing principle" in the case of man is commonly referred to as abstracting, a capacity or potentiality shared with all living organisms.

The process of abstracting is set in motion by a perceptual discrimination of some sort, the detecting of a difference between ourselves and others, between figures and ground, between phenomena that are similar or contiguous. It is carried on by focusing attention on arbitrarily selected cues, by grouping and as signing potency to these cues, and by linking them with the whole array of past experience. Although some aspects of perceptual set are currently understood, the dynamics of the internal manipulation of cues and the attribution of meaning to them is still largely unfathomed.

COMMUNICATION IS CONTINUOUS. Communication with the physical world, or with other human beings, is not a thing, nor even a discrete act, but a continuing condition of life, a process that ebbs and flows with changes in the environment and fluctuations in our needs. "It is only the imperfection of the fit, the difference between organism and environment, coupled with the perpetual tendency to improve the fit, that allows the working parts to work and makes them continue to work." 14 This process has no beginning nor end, even in sleep or under conditions of sensory deprivation, for man is a homeostatic rather than static mechanism.

The brain works as naturally as the kidneys and the blood-vessels. It is not dormant just because there is no conscious purpose to be served at the moment. If it were, indeed, a vast and intricate telephone exchange, then it should be quiescent when the rest of the organism sleeps. . . . Instead of that, it goes right on manufacturing ideas-streams and deluges of ideas, that the sleeper is not using to think with about anything. But the brain is following its own law; it is actively translating experiences into symbols, in fulfillment of a basic need to do so. It carries on a constant process of ideation." The dynamic equilibrium of a mobile by Alexander Calder, in which the movement of each pendant upsets the balance among all the others until a new equilibrium is achieved, is an artistic expression of the "internal organizing principle" of which Boulding writes. Each new meaning derived from communication is both relieving and disturbing to man, leading to a ceaseless search for new ways of coping with his surroundings. Only in the organically deficient or the functionally disturbed, where rigidities in perceiving and abstracting are extreme, is this process retarded or temporarily arrested. For most, communication begins at birth or before and continues without serious interruption until death.

COMMUNICATION IS CIRCULAR. Defining communication as a continuous process of evolving meanings leaves the communicologist in the position of facing an altogether new problem with an outmoded vocabulary and strategy. The usual starting point in the analysis of any communicative act is to identify the critical elements. Normally this leads to categorization of a "sender," a "message," and a "receiver." Having defined the problem in structural terms, the investigator is then obliged to continue his analysis within the framework of this assumption. It is obvious, largely because grammar suggests it, that the elements must fall into some sort of pattern: A, then B, then C. It is not long before the conclusion is drawn that these entities not only occur in sequence, but that they are causally related. A sender causes, by means of a message, certain effects in a receiver. Communication originates with the speaker, it terminates in a listener. No matter how appealing this may appear in its clarity and simplicity, it generates more problems than it solves. A structural approach, with its static elements and terminal implications, does not fit a process like communication.

----------------------

16. The tendency to talk about abstracting in static rather than dynamic terms is found even in some psychiatric literature where trauma are sometimes regarded as psychological injuries with a well-defined locus in childhood. It seems plausible that many perfectly ordinary events actually become traumatized by continual abstraction of these episodes in a nervous system with narrow or illusory assumptions until the original event becomes so shocking in its meaning that it can no longer be admitted to consciousness. Indeed, if experiences did not continue to be processed in the nervous system, there would be no possibility of cure for the disturbed individual.

17. Recently, through the influence of writings in cybernetics, another causal link, the reverse of the above, has been added to include the feedback of information in the opposite direction. This addition, while compensating for some of the naïveté of the earlier explanation, has not produced a radical change in the mode of analysis employed in studying human interaction.

18. Arthur Clarke, "Messages from the Invisible Universe," New York Times Magazine (November 30, 1958), p. 34.

18 Structural terminology is not outmoded, of course, when structural aspects of communication are studied. The earlier terminology would seem to continue to be of value in research on public address where there is considerable stability in the roles of speaker and audience.

-----------------------

"There is," according to Arthur Clarke, "no demarcation of a boundary between the parts in a communication process."

To erect such "lines of demarcation" cannot help but obscure the circular character of communication." New conceptual opportunities may arise if functional terms, such as sending and receiving-or better, encoding and decoding-are substituted for the former labels. It is clear, then, that these are operations and that, as such, they may assume a variety of patterns: symbolizing and interpreting may go on in a single person when he is alone; meanings may develop in two or more communicants simultaneously; messages, in the absence of either a source or receiver, may generate effects; meanings continue to flourish or deteriorate long after they are initiated, and so on. 2" There is a temptation to borrow the term "transceiver" from the engineers, for it summarizes the way encoding and decoding functions may be accommodated within a single organism. Communication seems more accurately described as a circular process in which the words "sender" and "receiver," when they have to be used at all, serve only to fix the point of view of the analyst who uses them. A structural approach seems ill-adapted to handling the internal dynamics of this complex process. If the actual variables were discrete and independent of one another, complexity in their relations would not be a deterrent, for the functional formula, Y = f (a, b, c, . . .), is available for handling such data. But if one has to cope with variables that are not only unstable, but that are interdependent as well, new modes of analysis are needed. Linear causality, with its sharp demarcation of independent and dependent variables, no longer gives sensible structure to observation.

We now merely note that methodologically the complexity that is added by reciprocal control may be denoted by the loss of a clear separation between independent and dependent variables. Each subject's behavior is at the same time a response to a past behavior of the other and a stimulus to a future behavior of the other; each behavior is in part dependent variable and in part independent variable; in no clear sense is it properly either of them. When signals must be treated simultaneously as both cause and effect, or where the communicative variables have reciprocating influences, a change in approach is necessary. A kind of "interdependent functionalism" might be pro posed by tampering with the functional formula so that each variable becomes a function of all other variables. For example, Y = / [a = / ( b, c, . . .), b -= f (a, c, . . j, c = I (a, b,...) 1. But the statistical complications associated with such an elaboration of the formula when combined with the difficulties in measuring communication variables underscore the need for alternative approaches.

Diagrammatic rendering of the interdependence and circularity of encoding and decoding processes may constitute such an alternative.

--------------------------

20 See John Newman, "Communication: A Dyadic Postulation," Journal of Communication (June, 1959).

21 A striking parallel is found in research on leadership in face-to-face groups. As long as investigators phrased their problems in terms of leaders and followers, that is in terms of persons, little progress was made during several decades of research. As soon as leadership was defined operationally, in terms of functions, important advances were made at once in describing various patterns of influence.

22 John Thibaut and Harold Kelley, The Social Psychology of Groups (Wiley, 1959), p. 2.

-----------------------------

COMMUNICATION IS UNREPEATABLE. The distinction being suggested here is between systems that are deterministic and mechanical, and those that are spontaneous and discretionary. In the former, the output of the system can be predicted as soon as the input is identified, for the system obeys a rigid logic that was built into it and which it is incapable of revising in its own interests. The system operates with minimal degrees of freedom. Repeat the input conditions and obtain identity of output. In an information-handling system of this type one can speak of the "same message" producing the "same effect," for the system does not have autonomous control of its own programming.

In the case of spontaneous systems, one that more accurately fits the communication of men, the system is governed by internal organizing principles which are themselves subject to change. There are substantial degrees of freedom which give the system a certain element of caprice, otherwise circularity would imply repeatability. In a spontaneous organism it is dangerous to assume that identical inputs will lead to the same output because the system has some control over its own internal design. One may start an engine over and over again, or return to the same office repeatedly. But one cannot expect the same message to generate identical meanings for all men, or even for a single man on different occasions.

The words of a message, even when faithfully repeated upon request, may provoke new insight, increase hostility, or generate boredom.

This is not to say that man never behaves in the same way on different occasions. Carried to an extreme the principle of unrepeatability would require totally erratic responses. This, in turn, would make a science of man virtually impossible. People do display consistency in behavior, the degree of the consistency reflecting the rigidity of assumptions required by the personality to maintain itself in encounters with reality. But, while behavior patterns may reappear from time to time, normally they do not repeat themselves precisely, nor are they triggered by identical environmental cues. Perhaps more central to developing a science of "healthy human behavior" is the recognition that modification rather than repeat ability is inherent in the human organism and that the exploitation of this capacity of the personality may be an important measure of its performance.

COMMUNICATION IS IRREVERSIBLE. Even in those systems that are autonomous there is the question of direction. Some processes are not only repeatable, but reversible as well. Heat will convert a block of ice into water, and finally into steam; a drop in temperature will liquefy the gas, and return it to a solid state.

Transposing the terminals on a storage battery can reverse the direction of chemical changes within. Reversible systems can return to earlier states by simply re tracing the steps by which they reached their present condition. A number of bodily functions such as breathing involve reversible processes.

Some systems, however, can only go forward from one state to another, from one equilibrium to a new equilibrium, never returning to their original state. "The basic cycles of nutrition, waking, and sleeping, and work and play must be maintained but they should be complemented by an adequate degree of one-way processes: of growth, reproduction, learning, and constructive or creative activities. With every breath, in and out, we grow older, but this can be complemented by a small residue of cumulative achievement." One can speak of the human skeleton as evolving from infancy to adulthood without the possibility of returning to earlier developmental stages. The same holds for human experiences. Our communication with ourselves and the world about us flows forward inexorably. Recent investigations of psychical phenomena through neurosurgery seem to bear this out.

Let me describe what seems to happen by means of a parable: Among millions and millions of nerve cells that clothe certain parts of the temporal lobes on each side, there runs a thread. It is the thread of time, the thread that runs through each succeeding wakeful hour of the individual's past life . . . Time's strip of film runs forward, never backward, even when resurrected from the past. It seems to proceed again at time's own unchanged pace. 24

23 Whyte, op. Cit., p. 117.

24 Wilder Penfield, "The Permanent Record of the Stream of Consciousness," Proceedings of the 14th International Congress of Psychology (June, 1954), pp. 67-68.

Here a figurative phrase, the "stream of consciousness," attains literal truth.

Human experience flows, as a stream, in a single direction leaving behind it a permanent record of man's communicative experience. Interruptions may mar the record as in the case of amnesia, or injury reduce its efficiency as in aphasia, but there is no "going back." One cannot start a man thinking, damage his self-respect or threaten his security, and then erase the effects and "begin again."

COMMUNICATION IS COMPLEX. Enough has already been said to suggest the complexity of human communication. If any doubt remains after considering the continuous, interdependent, irreversible and sometimes elusive functions of encoding and decoding, one has only to add the vast array of communicative purposes, social settings, and message forms, at the disposal of any communicant.

There is communication with self, with the physical environment; there is communication with others in face-to-face, organizational and societal contexts. The drives that require communication for their fulfillment stretch all the way from overcoming physical and psychological isolation through the resolution of differences, to catharsis and personality reorganization. In addition, the evolution of meaning is a process that goes forward at many levels of the personality, some times conscious, other times preconscious or subconscious; there are even channels of "crosstalk" linking these levels that still baffle and elude us. It is a rare message that does not contain both manifest and latent meanings, that does not illumine internal states as well as external realities. And the verbal symbols of a message are often played off against a backdrop of significant gestures and non verbal accompaniments that may contradict, elaborate, obscure or reinforce them. The study of man's communication with self and others seems both complicated and, at the same time, central to the full appreciation of what it is to be a man. 25

A PILOT MODEL

A pilot study is an "experimental experiment" in which an investigator attempts a gross manipulation of his variables to determine the feasibility of his study, clarify his assumptions and refine his measuring instruments. The drawings that follow are "pilot models" in the same spirit, for they are preliminary experiments in diagramming self-to-environment, self-to-self and self-to-other communication.

INTRA-PERSONAL COMMUNICATION

It may help to explain the diagrams that follow if the abstract elements and relations in the models are given concrete illustration by using a hypothetical case.

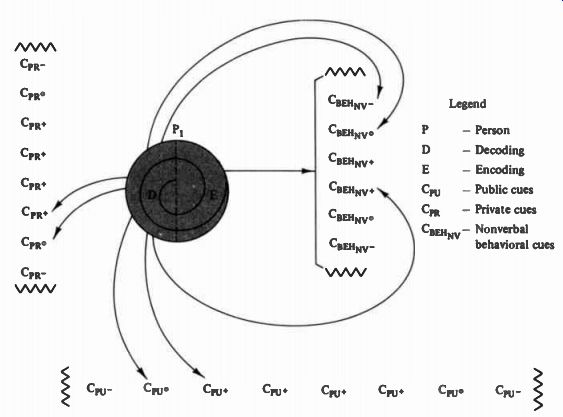

Let us assume a simple communicative setting. In Figure 1, a person (P1), let us say a Mr. A. sits alone in the reception room of a clinic waiting to see his doctor.

As a communication system Mr. A decodes (D), or assigns meaning to the various cues available in his perceptual field by transforming sensory discriminations into neuro-muscular sets (E) so that they are manifest to others in the form of verbal and nonverbal cues. Evidence is not available which will permit us to establish if encoding and decoding are separate functions of the organism, successive phases of a single on-going process, or the same operation viewed from opposite ends of the system, but it is reasonable to assume until we have solid proof that they are closely articulated and interdependent processes. The spiral line connecting encoding and decoding processes is used to give diagrammatic representation to the continuous, unrepeatable and irreversible nature of communication that was postulated earlier.

The meanings presented in Mr. A at any given moment will be a result of his alertness to, and detection of, objects and circumstances in his environment.

--------------------------

25 Man has been variously described as a symbolizer, abstracter, culture-creator, time binder, and communicator. More recently system theorists, reflecting current interests in cybernetics and information theory, have characterized him as an "open system." The parallel between the communication postulates above and the criteria for identifying open systems is striking. Allport specifies that in such systems there is "intake and output of matter and energy," "achievement and maintenance of homeostatic states," an "increase in complexity and differentiation of parts," and "there is more than mere intake and output of matter and energy; there is extensive transactional commerce with the environment." Gordon Allport, "The Open System in Personality Theory," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology (Volume 61, 1960), pp. 303-306.

--------------------------------------

FIGURE 1.

The lines terminating in arrows on Figure 1 can be used to indicate either the different stimuli that come into focus as Mr. A's attention shifts from moment to moment, or that a single "experience" may be a mosaic of many simultaneous perceptions. The direction of the arrows illustrates the postulate that meaning will be assigned to, rather than received from, the objects admitted to perception.

There are at least three sets of signs-or cues-to which Mr. A may attribute meaning in this setting. 26 Any of them may trigger interpretations or reactions of one kind or another. One set of cues derives from the environment itself.

These cues are identified in Figure 1 as public cues (Cry). To qualify as a public cue any object or sound or circumstance must fulfill two criteria. First, it must be a part of, or available to, the perceptual field of all potential communicants. Second, it must have been created prior to the event under analysis and must remain outside the control of the persons under observation. Two types of public cues can be distinguished. Natural cues, those supplied by the physical world without the intervention of man, include atmospheric conditions of temperature and humidity, the visual and tactual properties of minerals, the color and forms of vegetable life and climatic crises such as hurricanes and rainstorms. Artificial cues, those resulting from man's modification and manipulation of his environment, include the effects created by the processing and arranging of wood, steel and glass, the weaving and patterning of clothing, the control of climate through air or sound conditioning.

-----------------------

26 The more generic term of cues has been adopted to avoid some of the difficulties that attend the sign-symbol distinction.

--------------------------

As Mr. A glances about the office he may be aware of the arrangement of furniture, a worn carpet, a framed reproduction of a Miro painting, a slightly antiseptic odor, an end table covered with magazines. To any of them he may at tach significance, altering his attitude toward his doctor or himself. In some instances the cues may be authored and edited by a number of persons. The painting, for example, is a message from Joan Miro, its framing a message from the decorator, its choice and location a message from the doctor. All these cues are available potentially to anyone who enters the reception room. The perception of any specific cue, or the meaning assigned to it, however, will be similar for various people only to the extent that they possess the same sensory acuity, overlap ping fields of perception, parallel background experiences, and similar needs or purposes.

A second set of cues consists of those elements or events that are essentially private in nature, that come from sources not automatically available to any other person who enters a communicative field. Private cues might include the sounds heard through a pair of earphones, the sights visible through opera glasses, or the vast array of cues that have their origin in the taste buds or vis cera of the interpreter. In the case of Mr. A, the private cues (Crn) might include the words and pictures he finds as he riffles through a magazine, the potpourri of objects he finds in his pocket, or a sudden twitch of pain he notices in his chest. Public and private cues may be verbal or nonverbal in form, but the critical quality they share is that they were brought into existence and remain be yond the control of the communicants.

------------------------------

27 While this sort of intra-personal communication is usually identified as feedback, the connotation of this term may be unfortunate when applied loosely to human communication for it suggests a sender-receiver dualism where there may be none, and implies that a person receives information about his performance from his environment. Actions, however, are in capable of sending meanings back to the source. The individual acts and as he acts observes and interprets his own behavior. As long as this is understood the term need not cause difficulty but this does not always seem to be the case in the literature on communication.

----------------------------

Although no one else has yet entered the communicative field, Mr. A has to contend with one additional set of cues. These, however, are generated by, and are substantially under the control of, Mr. A himself. They consist of the observations he makes of himself as he turns the pages of his magazine, sees himself reflected in the mirror, or changes position in his chair. The articulation and movement of his body are as much a part of his phenomenological field as any other cue provided by the environment." Indeed if this were not true he would be incapable of coordinated acts. To turn a page requires the assessment of dozens of subtle muscular changes. These cues are identified in Figure 1 as behavioral, nonverbal cues ( CBI:11,0. They comprise the deliberate acts of Mr. A in straightening his tie or picking up a magazine as well as his unconscious manner isms in holding a cigarette or slouching in his chair. They differ from public cues in that they are initiated or controlled by the communicant himself. When public or private cues are assigned meaning, Mr. A is free to interpret as he will, but his meanings are circumscribed to some extent by the environment around him. Where his own behavior is involved, he controls (consciously or unconsciously) both the cues that are supplied and their interpretations as well. Two sets of lines are required in Figure 1 to reflect the circularity of this communication process, one to indicate the encoding of meaning in the nonverbal behavior of Mr. A, the other to show interpretation of these acts by Mr. A. The jagged lines ( ) at either end of the series of public, private and behavioral cues in Figure 1 simply illustrate that the number of cues to which meaning may be assigned is probably without limit. But, although unlimited in number, they can be ordered in terms of their attractiveness, or potency, for any viewer. Men do not occupy a neutral environment. The assumptive world of Mr.

A, a product of his sensory-motor successes and failures in the past, combined with his current appetites and needs, will establish his set toward the environment so that all available cues do not have equal valence for him. Each will carry a value that depends upon its power to assist or defeat him in pursuit of adequate meanings. Tentative valences have been assigned to the public, private, and behavioral cues in Figure 1 through the addition of a plus, zero or minus sign (±, 0, - ) following each of them.

The complexity of the process of abstracting can readily be illustrated through the diagram simply by specifying the precise objects which Mr. A includes or excludes from his perception. Research on dissonance and balance theory suggests the direction followed in the discrimination, organizing and interpreting of available cues.28 Unless other factors intervene, individuals tend to draw toward the cues to which positive valences can be assigned, that is toward cues capable of reinforcing past or emerging interpretations, and away from cues to which negative valences are attached or those that contradict established opinions and behavior patterns.

By a balanced state is meant a situation in which the relations among the entities fit together harmoniously; there is no stress towards change. A basic assumption is that sentiment relations and unit relations tend toward a balanced state. This means that sentiments are not entirely independent of the perceptions of unit connections between entities and that the latter, in turn, are not entirely independent of sentiments. Sentiments and unit relations are mutually interdependent. It also means that if a balanced state does not exist, then forces toward this state will arise. If a change is not possible, the state of imbalance will produce tension.

----------------------

28 See Leon Festinger, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Row Peterson, 1957) and Fritz Heider, The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations (Wiley, 1958).

29 Heider, Ibid., p. 201.

--------------------------

Successive diagrams of a particular communicative event could be made to demonstrate in a cognitively dissonant setting how a person avoids negatively-loaded cues, maximizes or minimizes competing cues, or re-assigns valences in order to produce consonance.

An illustration, even though oversimplified, will suggest the course of Mr. A's communication with himself. At the moment he is faintly aware of an anti septic odor in the room, which reinforces his confidence in the doctor's ability to diagnose his illness (Cpu+). As he glances through a magazine CO) he is conscious of how comfortable his chair feels after a long day on his feet CpR+). Looking up, he glances at the Miro reproduction on the wall, but is unable to de cipher it (Cpu0). He decides to call the nurse. As he rises he clumsily drops his magazine (Citiaim.- I and stoops to pick it up, crosses the room (CBEHm.0), and rings the call bell firmly and with dignity (C REHNv+).

INTERPERSONAL COMMUNICATION

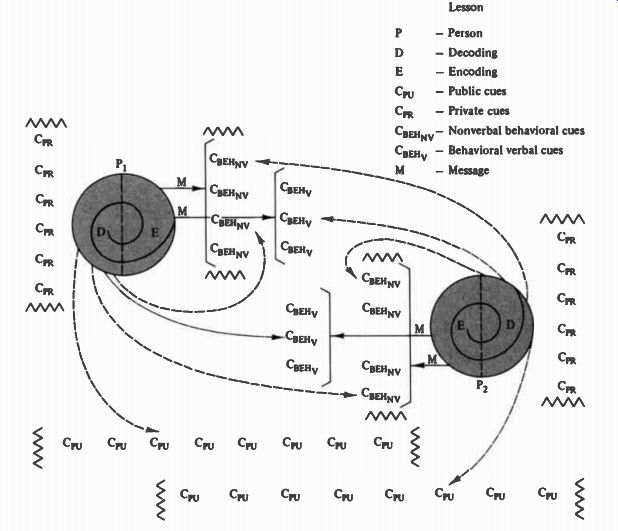

FIGURE 2.

The communication process is complicated still further in Figure 2 by the appearance of a second person (P,), let us say Dr. B, who enters the reception room to look for his next patient. The perceptual field of Dr. B, as that of Mr. A, will include the public cues supplied by the environment (Cpu). These cues, how ever, will not be identical for both persons, nor will they carry the same valences, because of differences in their backgrounds and immediate purposes. Dr. B may notice the time on the wall clock or the absence of other patients, and he may as sign different valences to the disarray of magazines on the table or to the Miro print. In addition, Dr. B will be interpreting private cues (Cpu) that belong exclusively to his own phenomenological field, such as his own fatigue at the moment, and these may alter the interpretations he attaches to Mr. A's conduct. Finally, there are the behavioral cues (CitEii, v) that accompany his own movements to which he must be tuned in order to act with reasonable efficiency.

Even before any verbal exchange takes place, however, there will be a shift in communicative orientation of both individuals. As Mr. A and Dr. B become aware of the presence of the other (sometimes before), each will become more self-conscious, more acutely aware of his own acts, and more alert to the nonverbal cues of the other as an aid to defining their relationship. Each will bring his own actions under closer surveillance and greater control. The doctor, as he enters, may assume a professional air as a means of keeping the patient at the proper psychological distance; the patient, upon hearing the door open, may hastily straighten his tie to make a good impression. A heightened sensitivity and a shift from environmental to behavioral cues identifies the process of social facilitation. Men do not act-or communicate-in private as they do in the presence of others. While audiences represent a special case of social facilitation, and mobs an unusually powerful and dramatic one, the mere appearance of a second person in an elevator or office will change the character and content of self-to-self communication in both parties.3° At some point in their contact, and well before they have spoken, Mr. A and Dr. B will have become sufficiently aware of each other that it is possible to speak of behavioral cues as comprising a message (M). That is, each person will begin to regulate the cues he provides the other, each will recognize the possible meanings the other may attach to his actions, and each will begin to interpret his own acts as if he were the other. These two features, the deliberate choice and control of cues and the projection of interpretation, constitute what is criteria for identifying interpersonal messages.

30. See Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Sell in Everyday Life (Doubleday Anchor Books, 1959).

Dr. B, crossing the room, may initiate the conversation. Extending his hand, he says, "Mr. A! So glad to see you. How are you?" 31 At this point, despite the seeming simplicity of the setting and prosaic content of the message, Mr. A must solve a riddle in meaning of considerable complexity. In a nonclinical environment where the public cues would be different, perhaps on a street corner (Cm: ), Mr. A would regard this message (CHEH ) as no more than a social gesture, and he would respond in kind. This on the other hand, is a clinic (Cpu). Is this re mark, therefore, to be given the usual interpretation? Even here, the nonverbal cues I CHEHNO of Dr. B, the friendly facial expression and extended hand, may reinforce its usual meaning in spite of the special setting. On the other hand, these words (CBE%) may be interpreted only as showing the sympathetic interest of Dr. B in Mr. A. In this case, the message requires no answer at all but is a signal for Mr. A to come into the office. In spite of the clinical setting (Cpl .) and the gracious gesture (CHEHN,.), however, the last phrase (CHEH,.), because of a momentary hesitation just before it (CitEnNv), might be an invitation for Mr. A to begin giving an account of his symptoms. In deciphering the meaning, Mr. A will have to assign and reassign valences so that a coherent interpretation emerges. (No valences are assigned in Figure 2 because their positive, negative or neutral value would depend upon the interpretive decisions of Mr. A and Dr. B.) All three contexts, the environmental, behavioral and verbal will have to be scanned, assigned meanings, and compared in order for Mr. A to determine a suitable response.

Meanwhile, Dr. B is involved in weaving some interpretations of his own out of the cues he detects and the valences he assigns to them. Mr. A smiles back and says, "Nice to see you again, too. I wish the circumstances were different." At this moment Dr. B turns his attention from the carpet which needs repairing (Cpp) to Mr. A. How should he interpret this message? Since they are in a clinic (Cpv) it is not surprising that Mr. A should speak of the "circumstances" of his visit. Yet, could this be a warning that the visit concerns a serious medical problem rather than a trivial one? Mr. A's relaxed posture (CsEnN,) does not reinforce the former meaning, but his flushed face does (CHF:HNO. Or could this remark be no more than a semi-humorous reference to a past episode on the golf links (CpH) ? In any case, Dr. B, like Mr. A, must reduce the ambiguity in the situation by experimentally assigning meanings to public, private, nonverbal and verbal cues, relating them to the surrounding conditions of time and place, and determining the extent of congruence or incongruence in the meanings given them. Not until further verbal and nonverbal cues are supplied will Dr. B be confident that he has sized up the message properly.

-------------------------

31. We do not have, as yet, in spite of the efforts of linguists and students of nonverbal behavior, an adequate typology for identifying message cues. In the case of this simple re mark, is the unit of meaning the phoneme, morpheme, word, or phrase? And, in the case of nonverbal cues, is it to be bodily position, gesture, or some smaller unit? Until we have better descriptive categories the careful analysis of communicative acts cannot proceed very far.

----------------------------

This analysis suggests that meanings are assigned to verbal cues according to the same principles that govern the interpretations of all other cues. Indeed, this seems to be the case." 2 Meaning is cumulative (or ambiguity reductive) and grows as each new cue, of whatever type, is detected and assigned some sort of valence. Verbal cues are distinctive only in the sense that they constitute a special form of behavior, are finite in number, and are presented in a linear sequence.

One further clarification must be added concerning the transferability of cues. A public cue can be transformed into a private cue by manipulating it so that it is no longer available to all communicants. Mr. A may refold his coat so that a worn cuff cannot be seen by Dr. B, or the doctor may turn over his medical chart so that Mr. A cannot read his entry. Private cues may be converted into public ones. Mr. A may want Dr. B to see a cartoon in the New Yorker he has been reading or Dr. B may choose to show Mr. A the latest photograph of his daughter. Sometimes an action on the part of a communicant involves manipulating or altering an environmental cue. Dr. B may unconsciously rearrange the magazines on the table while speaking to Mr. A and, in this case, environmental and behavioral cues merge.

The aim of communication is to reduce uncertainty. Each cue has potential value in carrying out this purpose. But it requires that the organism be open to all available cues and that it be willing to alter meanings until a coherent and ad equate picture emerges. Conditionality becomes the criterion of functional communication which, according to Llewellyn Gross, "involves the attitude of thinking in terms of varying degrees and changing proportions; the habit of acting provisionally and instrumentally with a keen awareness of the qualifying influence of time, place, people, and circumstances upon aspirations and expectations; the emotional appreciation for varieties and nuances of feeling." "3 What is regarded in various academic fields as an "error of judgment," or "a communication breakdown," or a "personality disturbance," appears to be a consequence of a sort of communicative negligence. The nature of this negligence is intimated in what a British psychiatrist has called "The Law of the Total Situation." "4 To the extent that a person is unable to respond to the total situation-because he denies critical cues from the environment, distorts verbal or nonverbal cues from the opposite person, fails to revise inappropriate assumptions regarding time and place-to that extent will it be difficult, or impossible, for him to construct meanings that will allow him to function in productive and satisfying ways.

----------------------------

32. James M. Richards, "The Cue Additivity Principle in a Restricted Social Interaction Situation," Journal of Experimental Psychology (1952), p. 452.

33. Llewellyn Gross, "The Construction and Partial Standardization of a Scale for Measuring Self-Insight," Journal of Social Psychology (November, 1948), p. 222.

34. Henry Harris, The Group Approach to Leadership Testing (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1949), p. 258.

-------------------------------

The observance and disregard of the Law of the Total Situation can be documented again and again in human affairs, at the most intimate interpersonal levels, and at the most serious public levels. Since communicative negligence is so omnipresent, it might be refreshing to consider an instance that illustrates a sensitive observance of the Law of the Total Situation.

Betty Smith, writing in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, tells of a neighborhood custom. On the night before Christmas a child could win a tree if he stood with out falling while it was thrown at him. When Francie was ten and Neeley nine, they went to the lot and asked the owner to throw his biggest tree at the two of them. The small children clasped each other to meet the force of the great tree.

For just a moment the man agonized, wanting simply to give it to them, but knowing that if he did he would have to give away all his trees, and the next year no one would pay for a tree. Realizing he must do it, he threw the tree as hard as he could. Though the children almost fell, they were able to withstand the impact and claimed the tree. As they started to pick it up Francie heard the man shout after them, "And now get the hell out of here, you lousy bastards." There was no doubt about what he said. But Francie was able to hear beyond the rough words.

She knew that this tone of voice, on Christmas Eve, from one who had no other language really meant, "Merry Christmas, God bless you." The man could not have said that, and Francie recognized it. He used the only words he had and she was able to understand him, not from his words alone, but from the totality of time, place, personality, and circumstance.

The complexities of human communication present an unbelievably difficult challenge to the student of human affairs. To build a satisfactory theory about so complex an event through sole reliance upon the resources of ordinary language seems less and less promising. Any conceptual device which might give order to the many and volatile forces at work when people communicate deserves attention. The value of any theoretical innovation, such as a symbolic model, may be measured by its capacity to withstand critical attack, its value in prompting new hypotheses and data, or finally, by its contribution to the improvement of human communication. The pilot models described here may not fulfill any of these criteria completely, but they will have served a useful purpose if they prompt the search for better ways of representing the inner dynamics of the communication process. 35

35. Only slight modifications are needed to adapt these models for use in representing the dynamics of mass communication.

Also in Part 2:

- Communication Theory: Systems

- An Introduction to Cybernetics and Information Theory--Allan R. Broadhurst and Donald K. Darnell

- A Conceptual Model for Communications Research --Bruce H. Westley and Malcolm S. MacLean, Jr.

- A Transactional Model of Communication--Dean C. Barnlund

- A Helical Model of Communication--Frank E. X.

- Dance Speech System--Edward Mysak