Nineteen hundred forty-eight, the year in which Shannon's first papers were

published in the Bell System Technical Journal 1 was also the year of first

publication of Norbert Wiener's classic, Cybernetics: or Control and Communication

in the Animal and the Machine.2 The dual thrust of these seminal works spawned

the rapid popularization and dissemination of an almost entirely new vocabulary

in the communication field. "Bit," "entropy," "ergodic

theory," "feedback," "in formation" (in the mathematical

or statistical sense), "noise," "probability," "redundancy" and

many other terms were quickly integrated into communication terminology and

were extended by analogy from their original fields to al most any discipline

that had an interest in self-examination from the viewpoint of communication.

------------

by Frank E. X. Dance: From Frank E. X. Dance, "A Helical Model of Communication," Human Communication Theory (New York, 1967), 294-298. Reproduced with permission of the author and publisher.

1. Shannon, C. E., "The Mathematical Theory of Communication," Bell System Technical Journal. (July and October, 1948). 2 Wiener, N., Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1948.

-------------------------

"Feedback" became especially popular and justly so. The feedback concept has proved to be invaluable in clarifying many areas of human interaction that until its availability had been shadowily felt but inaccurately understood. In the area of human communication, the impact of the concept of feedback was most notable in the early fifties, when there was great propagation and support for the notion of the circularity of the communication process. Today, it seems probable that most people, if given a choice between describing the communication pro cess as linear or as circular, would opt in favor of circularity. One plausible inference is that at some time people generally felt that communication was probably linear. Now, both linearity and circularity suggest process, and either is in keeping with the general conviction that communication is a process. However, the geometrical analogy of the two choices is quite different. The feedback principle allowing for analysis of present behavior so as to alter future behavior on the basis of the success or failure of current behavior is the seeming basis for the popularity of the circular model. But which of the two figures is most accurate and appropriate for those seeking a geometrical-spatial visualization of the communication process? The circular-communication image does an excellent job of making the point that what and how one communicates has an effect that may alter future communication. The main shortcoming of this circular model is that if accurately understood, it also suggests that communication comes back, full-circle, to exactly the same point from which it started. This part of the circular analogy is manifestly erroneous and could be damaging in increasing an understanding of the communication process and in predicting any constraints for a communicative event.

The linear model does well in directing our attention to the forward direction of communication and to the fact that a word once uttered cannot be re called. The changing aspect of communication is also implied in a linear model.

However, the linear image betrays reality in not providing for a modification of communicative behavior in the future based upon communicative success or shortcomings in the past.

Neither model is flawless, nor is there much hope for a completely isomorphic geometric model of something as complex as human communication.

However, is there any other geometric figure that, although not perfect, has somewhat more success in helping us visualize the reality of human communication? Perhaps so.

In the past decade and a half, one specific geometrical figure has cropped up as a descriptive device in a number of disciplines. In the beautiful work on deoxyribonucleic acid and its role in the genetic determination of man, we are often reminded of the DNA molecule's helical shape. "The DNA molecule is a helix, a spiral that looks like a coiled ladder." 3 In another area, philosophy, we find Teil hard de Chardin saying:

-----------

3 "DNA's Code: Key to All Life." Special Reprint from Life, 1963.

-------------

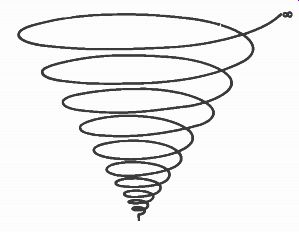

Like the geologist occupied in recording the movements of the earth, the faultings and foldings, the palaeontologist who fixes the position of the animal forms in time is apt to see in the past nothing but a monotonous series of homogeneous pulsations. In their records, the mammals succeeded the reptiles which succeeded the amphibians, just as the Alps replaced the Cimmerian Mountains which had in their turn replaced the Hercynian range. Hence forward we can and must break away from this view which lacks depth. We have no longer the crawling "sine" curve, but the spiral which springs upward as it turns. From one zoological layer to another, something is carried over: it grows jerkily, but ceaselessly, and in a constant direction.4 Although there are some who distinguish between a spiral and a helix on the basis that a spiral is two-dimensional and a helix three-dimensional, common usage, even in the scientific community, treats the two words as synonyms. The helix combines the desirable features of the straight line and of the circle while avoiding the weaknesses of either. In addition, the helix presents a rather fascinating variety of possibilities for representing pathologies of communication. If you take a helically-coiled spring, such as the child's toy that tumbles down stair cases by coiling in upon itself, and pull it full out in the vertical position, you can call to your imagination an entirely different kind of communication than that represented by compressing the spring as close as possible upon itself. If you extend the spring halfway and then compress just one side of the helix, you can envision a communicative process open in one dimension but closed in another.

At any and all times, the helix gives geometrical testimony to the concept that communication while moving forward is at the same moment coming back upon itself and being affected by its past behavior, for the coming curve of the helix is fundamentally affected by the curve from which it emerges. Yet, even though slowly, the helix can gradually free itself from its lower-level distortions. The communication process, like the helix, is constantly moving forward and yet is always to some degree dependent upon the past, which informs the present and the future. The helical communication model offers a flexible and useful geometrical image for considering the communication process.

--------------------

4. Teilhard de Chardin, P., The Phenomenon of Man. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1959, pp. 147-148.

5. Bruner, J. S., The Process of Education. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. 1965, p. 33.

------------------------

A helix can also be used to represent learning. Bruner hypothesizes that "any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development." 5 Thus, if one were to consider the construction of a helical communication curriculum, he would first try and set his normative objectives for the minimal communicative behaviors and knowledge needed for successful participation in any particular culture in any particular era, and then working from the top, or optimal, behaviors and knowledge down, he would try to penetrate slowly to the beginning point of the helix, watching closely at each turn of the helix for those behaviors that are new and those based upon behaviors already present in the developing cycle. Thus, we might eventually build a repertoire of skills and information that indicate the basic communicative elements needed at each stage in the progressive acquisition of the minimal communication behaviors and knowledge needed for successful human functioning. It would seem that such a study, when matched against already available knowledge concerning the developmental psychology and physiology of the child and adult, might result in a truly valuable and viable body of knowledge for those interested in speech communication education. Of course, there is no magic final curve of our personal communication helix, nor of the helical communication curriculum, for the helix by its very nature is always progressing upward even as it turns back upon itself and is affected by its own past conformations.

FIGURE 1. A Helical Spiral as a Representation of Human Communication.

If, then, we view an individual's communicative development in a helical fashion, we can suggest that from the moment of conception, the individual's communication helix begins to develop and move forward and in upon itself simultaneously. Freud stated, ". . . the original helplessness of human beings is thus the primal source of all moral motives." Rene Spitz extends this observation to suggest that the original helplessness of human beings is the ontogenetic base for all communicative behavior that progresses along with the development of the human being, from communicative behavior shared with infrahuman forms of being to that communicative behavior peculiar to human beings. Certainly the human being is never more helpless in terms of self-control and self-sufficiency than when he is in the womb. In essence, during his fetal state, the individual's action is his communication; what Spitz calls "discharge of drive" is the action.

At the same time this prenatal and neonatal discharge-activity can be viewed by an observer as communication. ". . . it has become clear, that at birth, and for a long time afterwards, action and communication are one. Action performed by the neonate, is only discharge of drive. But the same action, when viewed by the observer, contains a message from the neonate." Meerloo, in his essay, speaks to this point when he observes that, "Basically, separation is felt as a danger threatening the very survival of the individual entity. Communication, therefore, has an essentially anti-catastrophic part to play." 7 To compound our helical model we must remember that in the process of communicative self-emergence and self-identification the interaction with perceived others is essential. As a result, we have two or more helixes interacting and intertwined. It is in this inter action that the neonate develops his self-identity, his mind, his humanness. The process of this development is the focus of much interesting research that still awaits careful cross-indexing and systematizing and that is most meaningful to the field of human communication theory.8 In carefully observing the development of the child's communicative capacities and abilities, we may well continue to find valuable clues to the development of communicative capacities and abilities in the race. Haeckel's theorem, "Ontogeny is a brief and rapid recapitulation of phylogeny caused by the physiological functions of heredity and adaptation, "although seriously challenged, can still provide some provocative and thoughtful moments for those interested in the phylogenesis of human communication.

6. Spitz, R. A., No and Yes. New York: International Universities Press, Inc., 1957, pp. 145-146.

7. Meerloo, J. A. M., "Contributions of Psychiatry to the Study of Human Communication," Human Communication Theory, ed. Frank E. X. Dance. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1967, p. 133.

Vygotsky, L. S., Thought and Language. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1962.

Piaget, J., The Language and Thought of the Child. Cleveland, Ohio: The World Publishing Co., 1962.

9 Haeckel, E., Genere/le Morphologie der Organismen, II Band. S. 300 ( Berlin, 1866) ; as quoted in The Origin of Man by Mikhail Nesturkh. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1959, p. 20.

Also in Part 2:

- Communication Theory: Systems

- An Introduction to Cybernetics and Information Theory--Allan R. Broadhurst and Donald K. Darnell

- A Conceptual Model for Communications Research --Bruce H. Westley and Malcolm S. MacLean, Jr.

- A Transactional Model of Communication--Dean C. Barnlund

- A Helical Model of Communication--Frank E. X. Dance

- Speech System--Edward Mysak