Common to the concepts of balance, congruity, and dissonance is the notion

that thoughts, beliefs, attitudes, and behavior tend to organize themselves

in meaningful and sensible ways.' Members of the White Citizens Council do

not ordinarily contribute to NAACP. Adherents of the New Deal seldom support

Republican candidates. Christian Scientists do not enroll in medical schools.

And people who live in glass houses apparently do not throw stones. In this

respect the concept of consistency underscores and presumes human rationality.

It holds that behavior and attitudes are not only consistent to the objective

observer, but that individuals try to appear consistent to themselves. It

assumes that inconsistency is a noxious state setting up pressures to eliminate

it or reduce it. But in the ways that consistency in human behavior and attitudes

is achieved we see rather often a striking lack of rationality. A heavy smoker

cannot readily accept evidence relating cancer to smoking; 2 a socialist,

told that Hoover's endorsement of certain political slogans agreed perfectly

with his own, calls him a "typical hypocrite and a liar." " Allport

illustrates this irrationality in the following conversation: MR. X: The trouble

with Jews is that they only take care of their own group.

--- Robert B. Zajonc: From Robert B. Zajonc, "The Concepts of Balance, Congruity, and Dissonance," Public Opinion Quarterly, 1960, 24, 280-96. Reproduced with permission of the author and publisher. ---

1. The concepts of balance, congruity, and dissonance are due to Heider, Osgood and Tannenbaum, and Festinger, respectively. (F. Heider, "Attitudes and Cognitive Organization," Journal of Psychology, Vol. 21, 1946, pp. 107-112. C. E. Osgood and P. H. Tannenbaum, "The Principle of Congruity in the Prediction of Attitude Change," Psychological Review, Vol. 62, 1955, pp. 42-55. L. Festinger, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, Evanston, Ill., Row, Peterson, 1957.) For purposes of simplicity we will subsume these concepts under the label of consistency.

MR. Y: But the record of the Community Chest shows that they give more generously than non-Jews.

MR. X: That shows that they are always trying to buy favor and intrude in Christian affairs. They think of nothing but money; that is why there are so many Jewish bankers.

MR. Y: But a recent study shows that the percent of Jews in banking is proportionally much smaller than the percent of non-Jews.

MR. X: That's just it. They don't go in for respectable business. They would rather run night clubs.4 Thus, while the concept of consistency acknowledges man's rationality, observation of the means of its achievement simultaneously unveils his irrationality.

The psychoanalytic notion of rationalization is a literal example of a concept which assumes both rationality and irrationality-it holds, namely, that man strives to understand and justify painful experiences and to make them sensible and rational, but he employs completely irrational methods to achieve this end.

The concepts of consistency are not novel. Nor are they indigenous to the study of attitudes, behavior, or personality. These concepts have appeared in various forms in almost all sciences. It has been argued by some that it is the existence of consistencies in the universe that made science possible, and by others that consistencies in the universe are a proof of divine power.5 There is, of course, a question of whether consistencies are "real" or mere products of ingenious abstraction and conceptualization. For it would be entirely possible to categorize natural phenomena in such a haphazard way that instead of order, unity, and consistency, one would see a picture of utter chaos. If we were to eliminate one of the spatial dimensions from the conception of the physical world, the consistencies we now know and the consistencies which allow us to make reliable predictions would be vastly depleted.

------------------------

2. Festinger, op. cit., pp. 153-156.

3. H. B. Lewis, "Studies in the Principles of Judgments and Attitudes: IV. The Operation of 'Prestige Suggestion'," Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 14, 1941, pp. 229-256.

4. G. W. Allport, The Nature of Prejudice, Cambridge, Mass., Addison-Wesley, 1954.

5 W. P. Montague, Belief Unbound, New Haven, Conn., Yale University Press, 1930, pp. 70-73.

-------------------------

The concept of consistency in man is, then, a special case of the concept of universal consistency. The fascination with this concept led some psychologists to rather extreme positions. Franke, for instance, wrote, ". . . the unity of a person can be traced in each instant of his life. There is nothing in character that contradicts itself. If a person who is known to us seems to be incongruous with him self that is only an indication of the inadequacy and superficiality of our previous observations." 6 This sort of hypothesis is, of course, incapable of either verification or disproof and therefore has no significant consequences.

Empirical investigations employing the concepts of consistency have been carried out for many years. Not until recently, however, has there been a programmatic and systematic effort to explore with precision and detail their particular consequences for behavior and attitudes. The greatest impetus to the study of attitudinal consistency was given recently by Festinger and his students. In addition to those already named, other related contributions in this area are those of Newcomb, who introduced the concept of "strain toward symmetry," 7 and of Cartwright and Harary, who expressed the notions of balance and symmetry in a mathematical form.9 These notions all assume inconsistency to be a painful or at least psychologically uncomfortable state, but they differ in the generality of application. The most restrictive and specific is the principle of congruity, since it restricts itself to the problems of the effects of information about objects and events on the attitudes toward the source of information. The most general is the notion of cognitive dissonance, since it considers consistency among any cognitions. In between are the notions of balance and symmetry, which consider attitudes toward people and objects in relation to one another, either within one per son's cognitive structure, as in the case of Heider's theory of balance, or among a given group of individuals, as in the case of Newcomb's strain toward symmetry.

It is the purpose of this paper to survey these concepts and to consider their implications for theory and research on attitudes.

THE CONCEPTS OF BALANCE AND STRAIN TOWARD SYMMETRY

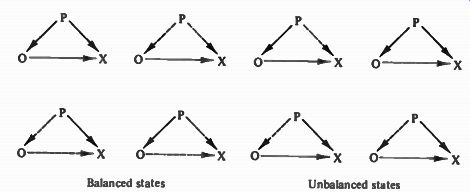

FIGURE 1 . Examples of balanced and unbalanced states according to Heider's

definition of balance. Solid lines represent positive, and broken lines negative,

relations.

--------------------------------

R. Franke, "Gang und Character," Beihefte, Zeitschrilt für angewandte Psychologie, No. 58, 1931, p. 45.

7. T. M. Newcomb, "An Approach to the Study of Communicative Acts," Psychological Review, Vol. 60, 1953, pp. 393-404.

8. D. Cartwright and F. Harary, "Structural Balance: A Generalization of Heider's Theory," Psychological Review, Vol. 63, 1956, pp. 277-293.

9. Heider, op. cit.

---------------------------

The earliest formalization of consistency is attributed to Heider,9 who was concerned with the way relations among persons involving some impersonal entity are cognitively experienced by the individual. The consistencies in which Heider was interested were those to be found in the ways people view their relations with other people and with the environment. The analysis was limited to two persons, labeled P and 0, with P as the focus of the analysis and with 0 representing some other person, and to one impersonal entity, which could be a physical object, an idea, an event, or the like, labeled X. The object of Heider's inquiry was to discover how relations among P, 0, and X are organized in P's cognitive structure, and whether there exist recurrent and systematic tendencies in the way these relations are experienced. Two types of relation, liking (L) and so-called U, or unit, relations (such as possession, cause, similarity, and the like) were distinguished. On the basis of incidental observations and intuitive judgment, probably, Heider proposed that the person's ( P's) cognitive structure representing relations among P, 0, and X are either what he termed "balanced" or "unbalanced." In particular, he proposed, "In the case of three entities, a balanced state exists if all three relations are positive in all respects or if two are negative and one positive." Thus a balanced state is obtained when, for instance, P likes 0, P likes X, and 0 likes X; or when P likes 0, P dislikes X, and 0 dislikes X; or when P dislikes 0, P likes X, and 0 dislikes X (see Figure 1). It should be noted that within Heider's conception a relation may be either positive or negative; degrees of liking cannot be represented. The fundamental assumption of balance theory is that an unbalanced state produces tension and generates forces to restore balance. This hypothesis was tested by Jordan.'° He presented subjects with hypothetical situations involving two persons and an impersonal entity to rate for "pleasantness." Half the situations were by Heider's definition balanced and half unbalanced. Jordan's data showed somewhat higher unpleasantness ratings for the unbalanced than the balanced situations.

-------------------

10. N. Jordan, "Behavioral Forces That Are a Function of Attitudes and of Cognitive Organization," Human Relations, Vol. 6, 1953, pp. 273-287.

11. Cartwright and Harary, op. cit.

----------------------------

Cartwright and Harary " have cast Heider's formulation in graph-theoretical terms and derived some interesting consequences beyond those stated by Heider. Heider's concept allows either a balanced or an unbalanced state. Cartwright and Harary have constructed a more general definition of balance, with balance treated as a matter of degree, ranging from 0 to 1. Furthermore, their formulation of balance theory extended the notion to any number of entities, and a experiment by Morrissette 12 similar in design to that of Jordan obtained evidence for Cartwright and Harary's derivations.

A notion very similar to balance was advanced by Newcomb in 1953.'3 In addition to substituting A for P, and B for 0, Newcomb took Heider's notion of balance out of one person's head and applied it to communication among people.

Newcomb postulates a "strain toward symmetry" which leads to a communality of attitudes of two people (A and B) oriented toward an object (X). The strain toward symmetry influences communication between A and B so as to bring their attitudes toward X into congruence. Newcomb cites a study in which a questionnaire was administered to college students in 1951 following the dismissal of General MacArthur by President Truman. Data were obtained on students' attitudes toward Truman's decision and their perception of the attitudes of their closest friends. Of the pro-Truman subjects 48 said that their closest friends favored Truman and none that their closest friends were opposed to his decision.

-----------------------

12. J. Morrissette, "An Experimental Study of the Theory of Structural Balance," Human Relations, Vol. 11, 1958, pp. 239-254.

13. Newcomb, op. cit.

14. T. M. Newcomb, "The Prediction of Interpersonal Attraction," American Psychologist, Vol. 11, 1956, pp. 575-586.

15. L. Festinger, K. Back, S. Schachter, H. H. Kelley, and J. Thibaut, Theory and Experi ment in Social Communication, Ann Arbor, Mich., University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research, 1950.

----------------------

Of the anti-Truman subjects only 2 said that their friends were generally pro Truman and 34 that they were anti-Truman. In a longitudinal study, considerably more convincing evidence was obtained in support of the strain-toward-symmetry hypothesis. In 1954 Newcomb set up a house at the University of Michigan which offered free rent for one semester for seventeen students who would serve as subjects. The residents of the house were observed, questioned, and rated for four to five hours a week during the entire semester. The study was then repeated with another set of seventeen students. The findings revealed a tendency for those who were attracted to one another to agree on many matters, including the way they perceived their own selves and their ideal selves, and their attractions for other group members. Moreover, in line with the prediction, these similarities, real as well as perceived, seemed to increase over time." Newcomb also cites the work of Festinger and his associates on social communication 15 in support of his hypothesis. Festinger's studies on communication have clearly shown that the tendency to influence other group members to ward one's own opinion increases with the degree of attraction. More recently Burdick and Burnes reported two experiments in which measures of skin resistance (GSR) were obtained as an index of emotional reaction in the presence of balanced and unbalanced situations." They observed significant differences in skin resistance depending on whether the subjects agreed or disagreed with a "well-liked experimenter." In the second experiment Burdick and Burnes found that subjects who liked the experimenter tended to change their opinions toward greater agreement with his, and those who disliked him, toward greater disagreement. There are, of course, many other studies to show that the attitude toward the communicator determines his persuasive effectiveness. Hovland and his co-workers have demonstrated these effects in several studies." They have also shown, however, that these effects are fleeting; that is, the attitude change produced by the communication seems to dissipate over time. Their interpretation is that over time subjects tend to dissociate the source from the message and are therefore subsequently less influenced by the prestige of the communicator. This proposition was substantiated by Kelman and Hovlands who produced attitude changes with a prestigeful communicator and retested subjects after a four-week interval with and without reminding the subjects about the communicator. The results showed that the permanence of the attitude change depended on the association with the source.

In general, the consequences of balance theories have up to now been rather limited. Except for Newcomb's longitudinal study, the experimental situations dealt mostly with subjects who responded to hypothetical situations, and direct evidence is scarce. The Burdick and Burnes experiment is the only one bearing more directly on the assumption that imbalance or asymmetry produces tension.

Cartwright and Harary's mathematization of the concept of balance should, how ever, lead to important empirical and theoretical developments. One difficulty is that there really has not been a serious experimental attempt to disprove the theory. It is conceivable that some situations defined by the theory as unbalanced may in fact remain stable and produce no significant pressures toward balance.

----------------------

16. II. A. Burdick and A. J. Burnes, "A Test of 'Strain toward Symmetry' Theories," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 57, 1958, pp. 367-369.

17. C. I. Hovland, I. L. Janis, and H. H. Kelley, Communication and Persuasion: Psycho logical Studies of Opinion Change, New Haven, Conn., Yale University Press, 1953.

18. H. C. Kelman and C. I. Hovland, "'Reinstatement' of the Communicator in Delayed Measurement of Opinion Change," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 48, 1953, pp. 327-335.

-----------------------------

Festinger once inquired in a jocular mood if it followed from balance theory that since he likes chicken, and since chickens like chicken feed, he must also like chicken feed or else experience the tension of imbalance. While this counter-example is, of course, not to be taken seriously, it does point to some difficulties in the concepts of balance. It is not clear from Heider's theory of balance and New comb's theory of symmetry what predictions are to be made when attraction of both P and 0 toward X exists but when the origin and nature of these attractions are different. In other words, suppose both P and 0 like X but for different reasons and in entirely different ways, as was the case with Festinger and the chickens. Are the consequences of balance theory the same then as in the case where P and 0 like X for the same reasons and in the same way? It is also not clear, incidentally, what the consequences are when the relation between P and 0 is cooperative and when it is competitive. Two men vying for the hand of the same fair maiden might experience tension whether they are close friends or deadly enemies.

In a yet unpublished study conducted by Harburg and Price at the University of Michigan, students were asked to name two of their best friends. When those named were of opposite sexes, subjects reported they would feel uneasy if the two friends liked one another. In a subsequent experiment subjects were asked whether they desired their good friend to like, be neutral to, or dislike one of their strongly disliked acquaintances, and whether they desired the disliked acquaintance to like or dislike the friend. It will be recalled that in either case a balanced state obtains only if the two persons are negatively related to one an other. However, Harburg and Price found that 39 percent desired their friend to be liked by the disliked acquaintance, and only 24 percent to be disliked. More over, faced with the alternative that the disliked acquaintance dislikes their friend, 55 percent as opposed to 25 percent expressed uneasiness. These results are quite inconsistent with balance theory. Although one may want one's friends to dislike one's enemies, one may not want the enemies to dislike one's friends.

The reason for the latter may be simply a concern for the friends' welfare.

OSGOOD AND TANNENBAUM'S PRINCIPLE OF CONGRUITY

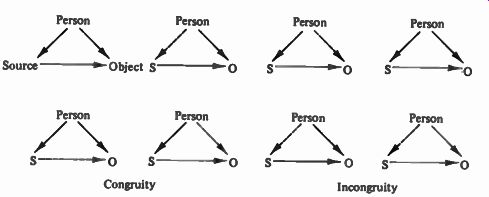

FIGURE 2. Examples of congruity and incongruity. Heavy lines represent assertions,

light lines represent attitudes. Solid heavy lines represent assertions which

imply a positive attitude on the part of the source, and broken heavy lines,

negative attitudes. Solid light lines represent positive, and broken light

lines negative, attitudes.

The principle of congruity, which is in fact a special case of balance, was advanced by Osgood and Tannenbaum in 1955." It deals specifically with the problem of direction of attitude change. The authors assume that "judgmental frames of reference tend toward maximal simplicity." Thus, since extreme "black-and-white," "all-or-nothing" judgments are simpler than refined ones, valuations tend to move toward extremes for in the words of the authors, there is "a continuing pressure toward polarization." Together with the notion of maximization of simplicity is the assumption of identity as being less complex than the discrimination of fine differences. Therefore, related "concepts" will tend to be evaluated in a similar manner. Given these assumptions, the principle of congruity holds that when change in evaluation or attitude occurs it always occurs in the direction of increased congruity with the prevailing frame of reference.

------------------

19. Osgood and Tannenbaum, op. cit.

------------------

The paradigm of congruity is that of an individual who is confronted with an assertion regarding a particular matter about which he believes and feels in a certain way, made by a person toward whom he also has some attitude. Given that Eisenhower is evaluated positively and freedom of the press also positively, and given that Eisenhower (+1 comes out in favor of freedom of the press (+), congruity is said to exist. But given that the Daily Worker is evaluated negatively, and given that the Daily Worker (-) comes out in favor of freedom of the press (+), incongruity is said to exist. Examples of congruity and incongruity are shown in Figure 2. The diagram shows the attitudes of a given individual toward the source and the object of the assertion. The assertions represented by heavy lines imply either positive or negative attitudes of the source toward the object.

It is clear from a comparison of Figures 1 and 2 that in terms of their formal properties, the definitions of balance and congruity are identical. Thus, incongruity is said to exist when the attitudes toward the source and the object are similar and the assertion is negative, or when they are dissimilar and the assertion is positive. In comparison, unbalanced states are defined as having either one or all negative relations, which is of course equivalent to the above. To the extent that the person's attitudes are congruent with those implied in the assertion, a stable state exists. When the attitudes toward the person and the assertion are incongruent, there will be a tendency to change the attitudes to ward the person and the object of the assertion in the direction of increased congruity. Tannenbaum obtained measures on 405 college students regarding their attitudes toward labor leaders, the Chicago Tribune, and Senator Robert Taft as sources, and toward legalized gambling, abstract art, and accelerated college pro grams as objects. Some time after the attitude scores were obtained, the subjects were presented with "highly realistic" newspaper clippings involving assertions made by the various sources regarding the concepts. In general, when the original attitudes toward the source and the concept were both positive and the assertion presented in the newspaper clippings was also positive, no significant attitude changes were observed in the results. When the original attitudes toward the source and the concept were negative and the assertion was positive, again no changes were obtained. As predicted, however, when a positively valued source was seen as making a positive assertion about a negatively valued concept, the attitude toward the source became less favorable, and toward the concept more favorable. Conversely, when a negatively valued source was seen as making a positive assertion about a positively valued concept, attitudes toward the source be came more favorable and toward the concept less favorable. The entire gamut of predicted changes was confirmed in Tannenbaum's data; it is summarized in the accompanying table, in which the direction of change is represented by either a plus or a minus sign, and the extent of change by either one or two such signs.

CHANGE OF ATTITUDE TOWARD THE SOURCE AND THE OBJECT WHEN POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE ASSERTIONS ARE MADE BY THE SOURCE

A further derivation of the congruity principle is that incongruity does not invariably produce attitude change, but that it may at times lead to incredulity on the part of the individual. When confronted by an assertion which stands in an incongruous relation to the person who made it, there will be a tendency not to believe that the person made the assertion, thus reducing incongruity.

There is a good deal of evidence supporting Osgood and Tannenbaum's principle of congruity. As early as 1921, H. T. Moore had subjects judge statements for their grammar, ethical infringements for their seriousness, and resolutions of the dominant seventh chord for their dissonance. After two and one-half months the subjects returned and were presented with judgments of "experts." This experimental manipulation resulted in 62 percent reversals of judgments on grammar, 50 percent of ethical judgments, and 43 percent of musical judgments. And in 1935 in a study on a similar problem of prestige suggestion, Sherif let subjects rank sixteen authors for their literary merit. Subsequently, the subjects were given sixteen passages presumably written by the various authors previously ranked. The subjects were asked to rank-order the passages for literary merit. Although in actuality all the passages were written by Robert Louis Stevenson, the subjects were able to rank the passages. Moreover, the correlations between the merit of the author and the merit of the passage ranged from between .33 to .53. These correlations are not very dramatic, yet they do represent some impact of attitude toward the source on attitude toward the pas sage.

With respect to incredulity, an interesting experiment was conducted recently by Jones and Kohler in which subjects learned statements which either supported their attitudes or were in disagreement with them. 22 Some of the statements were plausible and some implausible. The results were rather striking.

-------------------

20. H. T. Moore, "The Comparative Influence of Majority and Expert Opinion," American Journal of Psychology, Vol. 32, 1921, pp. 16-20.

21. M. Sherif, "An Experimental Study of Stereotypes," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 29, 1935, pp. 371-375.

----------------------

Subjects whose attitudes favored segregation learned plausible pro-segregation statements and implausible anti-segregation statements much more rapidly than plausible anti-segregation and implausible pro-segregation statements. The re verse was of course true for subjects whose attitudes favored desegregation.

While the principle of congruity presents no new ideas, it has a great advantage over the earlier attempts in its precision. Osgood and Tannenbaum have formulated the principle of congruity in quantitative terms allowing for precise pre dictions regarding the extent and direction of attitude change-predictions which in their studies were fairly well confirmed. While balance theory allows merely a dichotomy of attitudes, either positive or negative, the principle of congruity al lows refined measurements using Osgood's method of the semantic differential. Moreover, while it is not clear from Heider's statement of balance in just what direction changes will occur when an unbalanced state exists, such predictions can be made on the basis of the congruity principle.

------------------

22. E. E. Jones and R. Kohler, "The Effects of Plausibility on the Learning of Controversial Statements," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 57, 1958, pp. 315-320. 23 C. E. Osgood. "The Nature and Measurement of Meaning," Psychological Bulletin, Vol en, 1952, pp. 197-237. Festinger, op. cit., p. 13.

Ibid., p. 3.

------------------------

FESTINGER'S THEORY OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE

Perhaps the largest systematic body of data is that collected in the realm of Festinger's dissonance theory. The statement of the dissonance principle is simple. It holds that two elements of knowledge ". . . are in dissonant relation if, considering these two alone, the obverse of one element would follow from the other."

It further holds that dissonance ". . . being psychologically uncomfortable, will motivate the person to try to reduce dissonance and achieve consonance" and in addition to trying to reduce it, the person will actively avoid situations and information which would likely increase the dissonance." A number of rather interesting and provocative consequences follow from Festinger's dissonance hypothesis.

First, it is predicted that all decisions or choices result in dissonance to the extent that the alternative not chosen contains positive features which make it at tractive also, and the alternative chosen contains features which might have resulted in rejecting it. Hence after making a choice people seek evidence to con firm their decision and so reduce dissonance. In the Ehrlich experiment cited by Cohen . . . the finding was that new car owners noticed and read ads about the cars they had recently purchased more than ads about other cars. Post-decision dissonance was also shown to result in a change of attractiveness of the alternative involved in a decision. Brehm had female subjects rate eight appliances for desirability. Subsequently, the subjects were given a choice between two of the eight products, given the chosen product, and after some interpolated activity (consisting of reading research reports about four of the appliances) were asked to rate the products again. Half the subjects were given a choice between products which they rated in a similar manner, and half between products on which the ratings differed. Thus in the first case higher dissonance was to be expected than in the second. The prediction from dissonance theory that there should be an increase in the attractiveness of the chosen alternative and decrease in the attractiveness of the rejected alternative was on the whole confirmed. Moreover, the further implication was also confirmed that the pressure to reduce dissonance (which was accomplished in the above experiment by changes in attractiveness of the alternatives) varies directly with the extent of dissonance.

Another body of data accounted for by the dissonance hypothesis deals with situations in which the person is forced (either by reward or punishment) to ex press an opinion publicly or make a public judgment or statement which is contrary to his own opinions and beliefs. In cases where the person actually makes such a judgment or expresses an opinion contrary to his own as a result of a promised reward or threat, dissonance exists between the knowledge of the overt behavior of the person and his privately held beliefs. Festinger also argues that in the case of noncompliance dissonance will exist between the knowledge of overt behavior and the anticipation of reward and punishment.

An example of how dissonance theory accounts for forced-compliance data is given by Brehm. Brehm offered prizes to eighth-graders for eating disliked vegetables and obtained measures of how well the children liked the vegetables.

---------------------------

26. D. Ehrlich, I. Guttman, P. Scheinbach, and J. Mills, "Post-decision Exposure to Relevant Information," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 54, 1957, pp. 98-102.

27. J. Brehm, "Post-decision Changes in the Desirability of Alternatives," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 52, 1956, pp. 384-389.

28. J. Brehm, "Increasing Cognitive Dissonance by a Fait Accompli," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 58, 1959, pp. 379-382.

-----------------------

Children who ate the vegetables increased their liking for them. Of course, one might argue that a simpler explanation of the results is that the attractiveness of the prize generalized to the vegetable, or that, even more simply, the vegetables increased in utility because a reward came with them. However, this argument would also lead one to predict that the increment in attraction under such conditions is a direct function of the magnitude of the reward. Dissonance theory makes the opposite prediction, and therefore a test of the validity of the two explanations is possible. Data collected by Festinger and Carlsmith and by Aronson and Mills " support the dissonance point of view. In Festinger and Carlsmith's experiment subjects were offered either $20 or $1 for telling someone that an experience which had actually been quite boring had been rather enjoy able and interesting. When measures of the subjects' private opinions about their actual enjoyment of the task were taken, those who were to be paid only $1 for the false testimony showed considerably higher scores than those who were to be paid $20. Aronson and Mills, on the other hand, tested the effects of negative incentive. They invited college women to join a group requiring them to go through a process of initiation. For some women the initiation was quite severe, for others it was mild. The prediction from dissonance theory that those who had to undergo severe initiation would increase their attraction for the group more than those having no initiation or mild initiation was borne out.

------------------------

29. L. Festinger and J. M. Carlsmith, "Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 58, 1959, pp. 203-210.

30. E. Aronson and J. Mills, "The Effect of Severity of Initiation on Liking for a Group," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 59, 1959, pp. 177-181.

31. Ehrlich et al., op. cit.

32. J. Mills, E. Aronson, and H. Robinson, "Selectivity in Exposure to Information," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 59, 1959, pp. 250-253.

-------------------------

A third set of consequences of the theory of dissonance deals with exposure to information. Since dissonance occurs between cognitive elements, and since in formation may lead to change in these elements, the principle of dissonance should have a close bearing on the individual's commerce with information. In particular, the assumption that dissonance is a psychologically uncomfortable state leads to the prediction that individuals will seek out information reducing dissonance and avoid information increasing it. The study on automobile-advertising readership described above is a demonstration of this hypothesis."' In an other study Mills, Aronson, and Robinson gave college students a choice between an objective and a necessary examination?" Following the decision, the subjects were given articles about examinations presumably written by experts, and they were asked if they would like to read them. In addition, in order to vary the intensity of dissonance, half the subjects were told that the examination counted 70 percent toward the final grade, and half that it counted only 5 percent. The data were obtained in the form of rankings of the articles for preference. While there was a clear preference for reading articles containing positive information about the alternative chosen, no significant selective effects were found when the articles presented arguments against the given type of examination. Also, the authors failed to demonstrate effects relating selectivity in exposure to information to the magnitude of dissonance, in that no significant differences were found between subjects for whom the examination was quite important (70 percent of the final grade) and those for whom it was relatively unimportant (5 percent of the final grade). Festinger was able to account for many other results by means of the dissonance principle, and in general his theory is rather successful in organizing a di verse body of empirical knowledge by means of a limited number of fairly reasonable assumptions. Moreover, from these reasonable assumptions dissonance theory generated several nontrivial and non-obvious consequences. The negative relationship between the magnitude of incentive and attraction of the object of false testimony is not at all obvious. Also not obvious is the prediction of an in crease in proselytizing for a mystical belief following an event that clearly contradicts it. Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter studied a group of "seekers"--people who presumably received a message from outer space informing them of an incipient major flood.3 " When the flood failed to materialize on the critical date, instead of quietly withdrawing from the public scene, as one would expect, the "Seekers" summoned press representatives, gave extended interviews, and invited the public to visit them and be informed of the details of the whole affair. In a very recent study by Brehm, a "non-obvious" derivation from dissonance theory was tested. Brehm predicted that when forced to engage in an un pleasant activity, an individual's liking for this activity will increase more when he receives information essentially berating the activity than when he receives in formation promoting it. The results tended to support Brehm's prediction. Since negative information is said to increase dissonance, and since increased dissonance leads to an increased tendency to reduce it, and since the only means of dissonance reduction was increasing the attractiveness of the activity, such an in crease would in fact be expected.

-----------------------

33. L. Festinger, J. Riecken, and S. Schachter, When Prophecy Fails, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1956.

34. J. W. Brehm, "Attitudinal Consequences of Commitment to Unpleasant Behavior," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 60, 1960, pp. 379-383.

--------------------------

CONCLUSIONS

The theories and empirical work dealing with consistencies are mainly concerned with intra-individual phenomena, be it with relationships between one attitude and another, between attitudes and values, or information, or perception, or behavior, or the like. One exception is Newcomb's concept of "strain toward symmetry." Here the concern is primarily with the interplay of forces among individuals which results in uniformities or consistencies among them. There is no question that the concepts of consistency, and especially the theory of cognitive dissonance, account for many varied attitudinal phenomena. Of course, the various formulations of consistency do not pretend, nor are they able, to account completely for the phenomena they examine. Principles of consistency, like all other principles, are prefaced by the ceteris paribus preamble. Thus, when other factors are held constant, then the principles of consistency should be able to explain behavior and attitudes completely. But the question to be raised here is just what factors must be held constant and how important and significant, relative to consistency, are they.

Suppose a man feels hostile toward the British and also dislikes cricket. One might be tempted to conclude that if one of his attitudes were different he would experience the discomfort of incongruity. But there are probably many people whose attitudes toward the British and cricket are incongruent, although the exact proportions are not known and are hardly worth serious inquiry. But if such an inquiry were undertaken it would probably disclose that attitudes depend largely on the conditions under which they have been acquired. For one thing, it would show that the attitudes depend at least to some extent on the relationship of the attitude object to the individual's needs and fears, and that these may be stronger than forces toward balance. There are in this world things to be avoided and feared. A child bitten by a dog will not develop favorable attitudes toward dogs. And no matter how much he likes Popeye you can't make him like spinach, although according to balance theory he should.

The relationship between attitudes and values or needs has been explored, for instance, in The Authoritarian Personality, which appeared in 1950." The authors of this work hypothesized a close relationship between attitudes and values on the one hand and personality on the other. They assumed that the “…convictions of an individual often form a broad and coherent pattern, as if bound together by a mentality or spirit." They further assumed that ft. . . opinions, attitudes, and values depend on human needs and since personality is essentially an organization of needs, then personality may be regarded as a determinant of ideological preference." Thus The Authoritarian Personality approach also stresses consistency, but while the concepts of congruity, balance, and dissonance are satisfied with assuming a general tendency toward consistency, The Authoritarian Personality theory goes further in that it holds that the dynamic of consistency is to be found in personality, and it is personality which gives consistency meaning and direction. Attitudes and values are thus seen to be consistent among themselves and with one another because they are both consistent with the basic personality needs, and they are consistent with needs be cause they are determined by them.

--------------------

35. T. W. Adorno, E. Frenkel-Brunswik, D. J. Levinson, and R. N. Sanford, The Authoritarian Personality, New York, Harper, 1950.

------------------

The very ambitious research deriving from The Authoritarian Personality formulation encountered many difficulties and, mainly because of serious methodological and theoretical shortcomings, has gradually lost its popularity. However, some aspects of this general approach have been salvaged by others. Rosenberg, for instance, has shown that attitudes are intimately related to the capacity of the attitude object to be instrumental to the attainment of the individual's values." Carlson went a step further and has shown that, if the perceived instrumentality of the object with respect to a person's values and needs is changed, the attitude itself may be modified." These studies, while not assuming a general consistency principle, illustrate a special instance of consistency, namely that between attitudes and utility, or instrumentality of attitude objects, with respect to the person's values and needs.

The concepts of consistency bear a striking historical similarity to the concept of vacuum. According to an excellent account by Conant, for centuries the principle that nature abhors a vacuum served to account for various phenomena, such as the action of pumps, behavior of liquids in joined vessels, suction, and the like. The strength of everyday evidence was so overwhelming that the principle was seldom questioned. However, it was known that one cannot draw water to a height of more than 34 feet. The simplest solution of this problem was to reformulate the principle to read that "nature abhors a vacuum below 34 feet." This modified version of horror vacui again was satisfactory for the phenomena it dealt with, until it was discovered that "nature abhors a vacuum below 34 feet only when we deal with water." As Torricelli has shown, when it comes to mercury "nature abhors a vacuum below 30 inches." Displeased with the crudity of a principle which must accommodate numerous exceptions, Torricelli formulated the notion that it was the pressure of air acting upon the surface of the liquid which was responsible for the height to which one could draw liquid by the action of pumps. The 34-foot limit represented the weight of water which the air pressure on the surface of earth could maintain, and the 30-inch limit represented the weight of mercury that air pressure could maintain. This was an entirely different and revolutionary concept, and its consequences had drastic impact on physics. Human nature, on the other hand, is said to abhor inconsistency. For the time being the principle is quite adequate, since it accounts systematically for many phenomena, some of which have never been explained and all of which have never been explained by one principle. But already today there are exceptions to consistency and balance. Some people who spend a good portion of their earnings on insurance also gamble. The first action presumably is intended to protect them from risks, the other to expose them to risks. Almost everybody enjoys a magician. And the magician only creates dissonance--you see before you an event which you know to be impossible on the basis of previous knowledge--the obverse of what you see follows from what you know. If the art of magic is essentially the art of producing dissonance, and if human nature abhors dissonance, why is the art of magic still flourishing? If decisions are necessarily followed by dissonance, and if nature abhors dissonance, why are decisions ever made? Although it is true that those decisions which would ordinarily lead to great dissonance take a very long time to make, they are made anyway.

-----------------------

36. M. J. Rosenberg, "Cognitive Structure and Attitudinal Affect," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 53, 1956, pp. 367-372.

37. E. R. Carlson, "Attitude Change through Modification of Attitude Structure," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 52, 1956, pp. 256-261.

38. James B. Conant, On Understanding Science, New Haven, Conn., Yale University Press, 1947.

-----------------------------

And it is also true that human nature does not abhor dissonance absolutely, as nature abhors a vacuum. Human nature merely avoids dissonance, and it would follow from dissonance theory that decisions whose instrumental consequences would not be worth the dissonance to follow would never be made. There are thus far no data to support this hypothesis, nor data to disprove it.

According to Conant, horror vacui served an important purpose besides explaining and organizing some aspects of physical knowledge. Without it the discomfort of "exceptions to the rule" would never have been felt, and the important developments in theory might have been delayed considerably. If a formulation had then a virtue in being wrong, the theories of consistency do have this virtue. They do organize a large body of knowledge. Also, they point out exceptions, and thereby they demand a new formulation. It will not suffice simply to reformulate them so as to accommodate the exceptions. I doubt if Festinger would be satisfied with a modification of his dissonance principle which would read that dissonance, being psychologically uncomfortable, leads a person to actively avoid situations and information which would be likely to increase the dissonance, except when there is an opportunity to watch a magician. Also, simply to disprove the theories by counter-examples would not in itself constitute an important contribution. We would merely lose explanations of phenomena which had been explained. And it is doubtful that the theories of consistency could be rejected simply because of counterexamples. Only a theory which accounts for all the data that the consistency principles now account for, for all the exceptions to those principles, and for all the phenomena which these principles should now but do not consider, is capable of replacing them. It is only a matter of time until such a development takes place.

Also in Part 4:

- Communication Theory: Interaction

- The Concepts of Balance, Congruity, and Dissonance

- A Summary of Experimental Research in Ethos

- An Overview of Persuasibility Research

- The Functional Approach to the Study of Attitudes

- The Social Judgment-Involvement Approach to Attitude and Attitude Change

- Processes of Opinion Change

- The Communication