BEFORE YOU SPEAK

The product of radio broadcasting is music and the spoken word. Your most important job will be to produce the words, and your basic tool is the microphone. It is not difficult to learn how to use a microphone; the hard part is knowing what to say when it is turned on. In a very few minutes almost anyone could learn how to perform the fundamental operations of a disk jockey. If you can move a switch and play a record, you qualify. But that obviously is only the first step. Being able to read copy and make interesting and informative ad lib remarks is the warp and woof of effective broadcasting.

You must learn to have confidence in front of a microphone and not be afraid of it. Speak directly into it, loud enough so that the "pot" (volume control) does not have to be set excessively high. Be sure not to start talking until you are given the cue; you are not going to be heard while the microphone is turned off. If you are operating the controls yourself, take a breath before you open your mike channel. The first sound that comes out should be the syllable of a word rather than an intake of air. And most important of all, have in mind what you are going to say, right from the start.

READING COPY

A layman may not be aware of the importance to a broadcaster of being able to read aloud effectively. Good radio or television announcers are able to read without calling attention to the pages of copy in front of them. Television broadcasters use "prompter" sheets that are placed directly under the lens of the camera, so they can look at you when they talk. Sometimes comedians make comments about the prompter sheets (commonly called "idiot cards"), but normally announcers prefer to give the effect of speaking extemporaneously. Your ability to do this will determine to a large extent whether or not you will be successful on the air.

Style

Contrary to popular belief, voice quality is not especially important.

While well-modulated tones may be of some advantage, they are not essential. Style can compensate for almost any voice quality. If this were not the case, Louis Armstrong would never have succeeded as a vocalist.

The style you develop is an individual thing. It must reflect an aspect of your personality, one with which you are comfortable. When you read, it is important that you be the same person you are when you speak in normal conversation. You should be able to move in and out of these two forms of communication with ease and alacrity. Much of the time you will be called upon to "ad lib around the copy." Your style will develop over a long period of time. It will be closely tied to your personality and interests. If you are basically a serious per son, your style will reflect this. You will speak in a manner that will cause people to take you seriously and believe what you say. This characteristic is called credibility, and it is extremely valuable to a newscaster or commentator. The "personality" disk jockey who has a fast one-liner after every record may find it difficult to establish sufficient credibility to read a newscast convincingly. Individual style is a product of many factors: rate of delivery, tone of voice, type of comment, and most of all, pacing and timing.

Pacing and Timing

These two much-used terms are difficult to define. While they may be the most important elements in oral style, they are also the most elusive.

Pacing includes rate of delivery, but it refers also to variations in the rate. In baseball a pitcher may throw a change -up to catch a batter off guard.

An announcer may do the same thing: change delivery speed abruptly, to emphasize a phrase. The effectiveness of this technique is determined by the execution and by the phrase that is selected for emphasis. Timing is a close relative of pacing. It is an essential ingredient of comedy--the master of it was Jack Benny. Timing is the sense of knowing how long to "hold" on a word or a pause before picking up the next line. It is measured in fractions of seconds. The term liming is also used to refer to the judgment that is exercised in knowing when to say what. Anyone who has told an inappropriate joke at a party understands the importance of timing. Timing can mean knowing when to stop talking as well as when to start. Many good speeches, both on and off the air, have been ruined because they went on too long. The excessive time could be a matter of minutes or a matter of seconds.

All of the above elements, as well as many that will be mentioned later, refer to ad libbing as well as reading copy. But remember this:

Almost any adult can read. There is nothing very special about that. To succeed in broadcasting you will have to set yourself apart from the millions of other people. The copy you will be called upon to read could be almost anything. Usually it will be news, commercials, public service announcements, and general station continuity.

Accuracy

It is most important to read accurately, that is, to pronounce the word that is on the page rather than another word that sounds or looks similar.

It also means reading only the words on the page, and not deleting or adding words unintentionally. If the copy does not make sense you may have to change it, but this should be done before you go on the air. Even professionals with many years of experience are leery about reading copy "cold," without a rehearsal. If possible, take the time to actually read your copy out loud, so you can hear the sound of your own voice pronouncing the words. This will take longer than reading it silently, but the closer scrutiny usually pays off in the long run. Above all, make sure you understand what you are reading. Use a dictionary to look up meanings and correct pronunciations.

Clarity

A popular bumper sticker reads "Eschew Obfuscation" (look up the words-it's a funny line). Remember that your responsibility as a broad caster is to clarify meaning. Avoid trying to impress people with your knowledge: Use words they can understand. And pronounce each word so that it is recognizable. Lack of clarity may be the result of mispronouncing an unfamiliar word; more often, however, it is caused by carelessness in pronouncing familiar words. Be sure to vocalize all the syllables that are supposed to be sounded in every word. Get into the habit of doing this in everyday conversation, so it will come naturally to you when you speak on the radio. An abrupt change between the way you read and the way you extemporize will be painfully apparent.

Initial Sounds

A careless speaker often begins a word with the second syllable rather than the first. Do not be guilty of this. The fault most commonly occurs when a word begins with the same sound as the ending of the preceding word. "American intelligence" may come out as " `Merican lelligence." While the meaning may be understandable, the effect is slovenly, and the speaker is setting a poor example.

Middle Sounds

The dropping of middle sounds is referred to as "telescoping" words. It happens mostly with long words, but sometimes with short ones too. "Contemplation" may become "con'umplation." It is very common to hear "prob'ly" for "probably." However, not all tele scoping is incorrect. Among the British many such forms have become quite institutionalized. "Worcestershire" is properly pronounced "Woostersheer," and "halfpenny" is "hayp'ny." Closer to home, our word "extraordinary" is correctly pronounced "extrordinary." These are things that the radio announcer must come to know by using and examining the language.

Endings

Dropping the endings of words is a common fault of speech. Most frequently abused is the "ing" sound. Do not say, "comin' and goin' " even if it is the articulation of middle America. However, do not overemphasize endings either. You can round off the sound so it does not appear to be an affectation.

Pronunciation

Words are the stock of the radio announcer, just as lumber and nails are the stock of the carpenter. They must be used properly. As a broadcaster you are going to be heard by hundreds or thousands of people when you talk. Your responsibility is magnified by that amount. We expect radio and television announcers to pronounce words correctly, and we will emulate them if we have nothing else to use as a standard. Network announcers who reach millions of people are especially careful about pronunciation; they know that it is not only the general public that relies on them, but that announcers in local, small-market stations do too.

When I listen to the radio I don't expect announcers to be perfect, but I want them to know at least as much about the language as I do, and maybe a little more. If I feel that a speaker knows less than I do, I'll dial to another station because I want to learn something. Perhaps it is the same as it is in sports. I want to play tennis with someone who is just a little bit better than I am.

The question arises, Is pronunciation related to knowledge and intelligence? Maybe not, but it appears to be. If I hear mispronounced the name of a prominent public figure or of an often -referred -to place in the news, I lose confidence in the speaker. That attitude may not be justified, but it is there. In order to assist the announcer in establishing credibility, the news services periodically print pronunciation guides. Here is a typical one.

FIG. 1 Pronunciation guide. (Courtesy UPI.)

-PRONUNCIATION GUIDE- (FRIDAY) NEWS kMAGA, COLOMBIA -- AH-MAH-GAH' IDI AMIN ID' -EE AH-MEEN' MENAHEM BEGIN -- MSHN-AH'KEM BEW-GIN ZULFIKAR ALI BHUTTO -- ZOOL'-FEE-KAHR AH'-LEE BOO'TOH BOGOTA, COLOMBIA -- BOH-GOH-TAH' MORARJI DESAI MOH-RAHR'-JEE DEH-SY' KENYA -- KEEN'-YUH HENRY KNOCHE -- NAH'KEE LAETRILE LAY'-UH-TRIHL HENRIETTA LEITH -- LEITH VALERY GISCARD D'ESTAING VAH-LAY-REE' ZHEES-KAHR' DEH-STANG' NAIROBI, KENYA -- NY-ROH'-BEE PANMUNJOM, KOREA --PAN-MUN-JAHM RAWALPINDI, PAKISTAN -- RAH-WUHL-PIN'-DEE ANWAR SADAT AHN'-WAHR SAH-DAHT' PIERRE TRUDEAU TROO-DOH' ZIA UL-HAQ -- ZEE UHL-HAHK

People knowledgeable in some fields are more critical than those in others. Classical music buffs are perhaps the most critical of all. You should know how to pronounce the names of these frequently heard composers. The pronunciation guide is in slightly different form from the one used by the wire services, but it is one that you will often see used in broadcast scripts.

FIG. 2 Composers.

Johann Sebastian Bach (YO-hahn Seh-bahs-tiahn Bahkh) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (VOHLF-gong Ah-mah-DAY-oos MOAT -sari) Richard Wagner (REE-khard VAHG-ner) Ludwig van Beethoven (LOOD-vig vahn BAY-toe-vn) Franz Joseph Haydn (Frahnts YO-zef HIGH-dn) Giuseppe Verdi (Joo-ZEP-eh VAIR-dee) Giacomo Puccini (JA-ko-mo Poo-CHEE-nee) Franz Schubert (Frahnts SHOE-beart) Carl Maria von Weber (Karl Ma-REE-ah fun VAY-bear) Felix Mendelssohn (FAY-lix MEND-1-sohn) Frederic Chopin (Fray -day -REEK Show -PAN) Edvard Grieg (Ed-vard GREEG) Antonin Dvorak (AHN-toneen Duh-VOR-zhock) Peter Tchaikovsky (Peter Chi-KOFF-ski) Igor Stravinsky (EE-gor Strah-VIN-ski) Hector Berlioz (Eck -tor 3EAR-lee-oz) Claude Debussy (Clohde Duh-Beu-SEL) Now try pronouncing these names of works by famous composers.

FIG. 3 Musical works.

Peer Gynt Suite (Pair Gint Sweet) Die Fledermaus (Dee FLAY-der-mouse) La Traviata (Lah Trah-vee-AH-ta) La Boheme (Lah Bo-EHM) Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (EYE-neh KLY-neh NAHKHT-moo-zeek) Capriccio Espagnol (Kah-PREACH-ee-o .s-Pahn-YOLE) Le Coq D'Or Suite (Luh Cuk-DOOR Sweet) Die Walkure (Dee VAHL-cure-eh) Aida (Eye-EL-duh) Largo Al Factotum (Largo Ahl Fahk-TOE-tum) Common words may give you as much difficulty as hard-to-pronounce names. This is especially true when the words are similar to other words.

accept-except access-excess adapt-adopt affect-effect amplitude-aptitude are-our

Arthur-author ascent-accent climatic-climactic comprise-compromise consecrate-confiscate consolation-consultation disillusion-dissolution exit-exist immorality-immortality line-lion lose-loose Mongol-mongrel morning-mourning pictures-pitchers sex-sects statue-statute vocation-vacation wandered-wondered.

Some words are mispronounced because of the combination of sounds in sequence. Try these tongue twisters:

The existentialist called for specific statistics.

The President set a precedent for preserving precipitant performance.

Be careful not to interchange the "pre" sound and the "per" sound. P's and S's can be particularly troublesome because they tend to pop and hiss on a microphone. Try not to hit the P too hard or extend the S too long.

Placing the accent in the proper place can be another problem. Use a dictionary to find the correct pronunciation for each of the following words:

abdomen contractor hospitable acclimated despicable inquiry admirable dirigible irrefutable aspirant exquisite pretense autopsy finance recess comparable grimace research resources robust romance theater vehement' Emphasis One of the important principles in the study of semantics is that words are not containers of meaning. In the English language there are over 750,000 words. All but a few of them have not one but several meanings.

Therefore, meaning is contained in the speaker or the writer-not in the words. Words are the tools we use to communicate, and their meaning can be altered by the way we use them. For example, the meaning of a sentence can be changed if the emphasis is shifted from one word to another. How is this done? Consider first the devices used by writers.

John P. Moncur and Harrison M. Karr, Developing Your Speaking Voice, 2d ed.

(New York: Harper & Row, 1972), p. 226.

2 Ibid.

They can put a word in CAPITAL LETTERS; they can underline or use italics; they can use punctuation such as quotation marks or exclamation marks. Announcers, of course, cannot use these, but they can use vocal inflection. They can utilize change in volume, pitch, or rate of delivery.

See if you can alter the meaning of the following sentence by modifying the stress that you place on the words:

I can change meaning by emphasizing important words.

Vocal Inflection Vocal inflection is important for two reasons:

(1) It helps to hold the interest of the listener, and (2) it helps to communicate accurately what you mean. Meaning must be considered at the affective as well as the cognitive level. In other words, the emotional mood that you set will influence the intellectual meaning of the communication. An announcer must be sensitive enough to know when to adopt a serious, concerned tone of voice and to be able to project that feeling in speech. For example, a news item that describes a tragic event should not be read in the same analytical tone that one would use when reading a stock market report. It is, of course, inappropriate for an announcer maudlin when describing a tragedy, but it should be apparent to the listener that the announcer is a human being and has feelings like any one else.

Achieving the appropriate degree of vocal inflection is not easy.

People tend to speak in a monotone when they are talking casually to friends. Vocal inflection reveals emotions, and some individuals are reluctant to permit that. It may also be that strong vocal inflection is not necessary when you are standing very close to a person and can see facial expression and physical posture. But an audience can not see the face of the announcer; the communication comes only through the auditory sense. There is no body language in radio. Your entire message must come through the cone of a loudspeaker. Everything you mean must be heard.

Radio and television are mass media because messages are received simultaneously by large numbers of people. However, the announcer must not speak as though addressing a large group. Broadcasting is intimate in that the listener is not aware of the existence of the multitude of other listeners. As far as the listener is concerned, the voice on the radio is speaking to him or her alone. The listener expects to be treated as one unique person, not to be addressed in the plural, as if by a public speaker facing a large audience. An exception to this occurs when the President addresses the nation. In this case listeners know they are hearing a pre pared speech, and that each person is one of a large group. But even then, Presidents are inclined to use the less formal phrase, "my friends" or "my fellow Americans," rather than "ladies and gentlemen." When some announcers broadcast they will picture in their minds one person to represent the type of audience the station hopes to reach. It could be a man commuting to work, a woman working in the home, or a teenager coming home from school. If you read your copy to that person as though he or she were in the same room with you, you will have a good chance of achieving the kind of communication that reaches a large number of people in the same category. The best radio announcers are friendly, informal, sincere, and intimate.

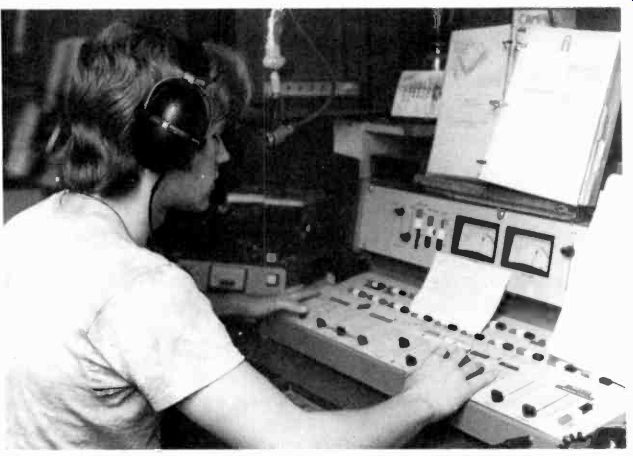

FIG. 4 Talking to the radio audience.

Rate

One of the factors of style is your rate of delivery. Students frequently ask me how fast they should talk. The answer is, no faster than is comfortable and fast enough to hold the interest of the audience. The rate, of course, will vary depending upon what you are reading, but in general I would suggest you talk as fast as you can without slurring or telescoping words or interfering with your vocal inflection. Consider this: Under laboratory conditions some people can comprehend an oral message that is played back on a tape recorder as fast as 400 words per minute-much faster than anyone can talk. Normally you speak at a rate of about 125 to 160 words per minute. This means that, while you are talking, the listener's mind can be engaged in other matters. Probably it is flitting from one thing to another every few seconds. You are only one of a number of stimuli competing for attention. If you speak too slowly, you are leaving enough time to focus on something else. Your listener may get the meaning of your sentence before you are through saying it, and then allow her or his mind to wander away. The copy you are reading out loud could be read silently by the listener in a fraction of the time it takes you to say it. So justify the time that the listener spends with you.

Remember that the listener is in complete control and can turn you off at any time.

Volume

How loud should you talk? Certainly there is no need to shout because microphone output can be amplified to any level necessary. However, remember that as you turn up the gain, you also pick up more ambient noise. Project the voice. Keep in mind that a certain minimum amount of vocal output is necessary for effective vocal inflection. The volume you use in everyday conversation may therefore not be sufficient for radio announcing. Again, remember that your message is filtered through a speaker cone. Your listeners can not see your lips move; nor can they observe the expression on your face. They get the meaning only from the sound of the words. Furthermore, they are not sitting with their ears glued to the speaker. Usually people are doing other things while they listen. If they are in a car, your message has to compete with the noise of traffic; at home the radio a person is listening to may be in the next room. What you say has to penetrate distance, inattention, and interference. With all this you may wonder if anybody will understand you at all.

AD LIBBING

Most of what was said in the preceding section on reading copy also applies to ad libbing-a broadcaster's term meaning to extemporize or to speak impromptu. Whether you are speaking from copy or without it, your articulation and enunciation must be clear enough so that you can be understood. At the same time it must be natural. Even though radio announcing is a lot of work and requires a good deal of preparation, you have to make it sound easy. The listener should not be able to perceive any strain or tension in your voice. Regardless of how much effort you put into writing your script or preparing your ad libs, your remarks should sound spontaneous, as if they were just welling up from within you. The fact that so many good announcers sound this way is deceptive.

It tends to make one think that a beginner can sit down and do the same thing with no effort or preparation. It may seem like a contradiction in terms when I say that your ad libs should be prepared, but that is exactly what they should be. Most ad lib comments have been thought about in advance-sometimes even written down. Entertainers with many years of experience can rely on their wits, but they have much background to call upon.

Most of your ad libbing you will do as a disk jockey between records. Probably the station you work for will have a policy about how much you should talk--and maybe even what you should say. A station may want you to talk after every record, or they may want you to play a "set" of two or three records. There may be specific times when you are to give time signals and weather reports. There may also be catch phrases or slogans prepared for you, to promote the station. Very likely there will be guidelines for the length of time you are to talk. Usually it is short and for a good reason. It is very difficult to sustain audience attention with an extended ad lib. You are not being paid as an entertainer. If there is humor in your remarks, it must be direct, succinct, and to the point. Some station managers say, "be a personality, but do it in not more than twenty seconds." Most disk jockeys would like to talk more than they are allowed to, but some that I have known feel that any talk is an imposition on the listener. If you fall into the second category, consider this: Those who want only music will buy phonographs and maybe even eight-track tape players for their cars. People who listen to the radio do so because they want to hear talk as well as music. Talk is not an imposition; the voice on the air is company for someone who is alone. It also provides information and entertainment. If talk were not valuable and desirable, it would have been dropped from broadcasting long ago. The important thing is to take a positive attitude toward what you say. Do not feel that you have to apologize for interrupting the music. You must be able to believe that the commercial or the public service announcement you are reading or talking about is important and that some people will listen to it and act upon what you tell them. Remember that your job is to sell the product, whether it be used cars, the United Crusade, or your own radio station.

Reading what is written for you is one thing, but how do you ad lib effectively? There is no easy answer. It will depend largely upon your own personality and interests. For the most part, disk jockeys talk about the records they are playing. So the first requisite is for you to know something about your artists and their music. The second is to choose such bits from the information you have as will make good ad lib re marks. Probably no one can prescribe a formula. All the rules can be, and are, broken by professionals once they get established. But here are a few guidelines that may prove helpful for the beginner:

1. Do not use broadcast jargon. Speak in language that is generally understood by the public rather than in technical terms. If you say you are operating combo and watching your VU meter, nobody is going to know what you are talking about.

2. Avoid using trite phrases repeatedly. It is easy to fall into the habit of relying on trite phrases, but their repeated use is annoying. A few examples are "Let's see now . . ."; "You know . . .": and "Here's a little bit of.. . ." These expressions are just fillers that people utter while they are thinking of what they really want to say. Your talk will be greatly enhanced if you leave them out.

3. Do not carry on private conversations with someone in the control room. Have your fun, but let the audience in on it too. If something happens that makes you laugh, tell the rest of us about it. We'll feel left out otherwise. A certain amount of this sort of cutting up may be all right, but don't let it go too far. Some station managers will say not to let it happen at all.

4. Do not sell yourself or the station too hard. Resist the temptation of telling the listeners what a great show you have and what a marvelous station it is. Let them decide that for themselves. Repeating your own name or the call letters of the station after every record gets very tire some.

5. Avoid anticlimactic words and phrases at the end of your ad lib. All too often the beginner (and sometimes the "old pro") fails to recognize the appropriate end of the ad lib and adds a phrase or two that ruins the effect. It is the same as trying to explain a joke after you have told it the impact is lost. To avoid this, have your hand on the switch that starts the next record before you finish your remark. Hit the music at the climax of your ad lib. If they don't get it, there is nothing you can do about it.

6. Do not be negative about any announcement you read or any pro gram you put on the air. If there is a commercial or a public service announcement you dislike, talk to the program director about it privately, but never put it down on the air. Remember that someone had a good reason for scheduling it. Your job is to sell it. A program you introduce may not be to your taste, but it is entitled to the same respect as any other item on the schedule.

7. Do not use offensive language. Obscenity on the air is a violation of the penal code and of the Rules and Regulations of the Federal Communications Commission. However, other forms of offensive speech are to be avoided as well. Ethnic slurs and crude jokes have no place on the airwaves either.

Most of the restrictions are matters of common sense.

What to Talk About

What kind of ad lib remarks do meet the test of good broadcast practice? Aside from comments about the records and the weather, what does a disk jockey talk about?

1. Coming events. This is perhaps the most valuable service a disk jockey can provide. No one expects to hear anything particularly pro found on the radio these days-at least not on an everyday basis. But they would like to know what is going on. In a minute or less you can tell about an event that is coming up in the listening territory, giving most of the vital information. This is an area where the disk jockey should be well informed. He or she should have broad enough interests to talk about a variety of subjects. Movies, plays, sporting events, lectures, college courses, festivals, rodeos, dog shows-all are activities that would be of interest to someone. Sit down and make a list of all the public places you can think of in your broadcast area. Then set about to learn what is happening at each place. This alone will give you plenty to talk about.

2. Current events. The bulk of the news will probably be covered on the regularly scheduled newscasts, but there are always features and human interest items that you can talk about. Your comments need not be lengthy-better that they not be. Just a short reference, to pique the curiosity, will suffice. Read the newspaper every day as a matter of course. In addition, subscribe to a current events magazine. Talk to people about the news. You will find yourself making ad lib remarks on the air that were tried out first in conversation with your friends.

3. Current trends and fashions. A radio announcer should be abreast of the avant-garde. People are interested in new things that are happening even if they have no wish to become actively involved. As the purveyor of this information you are not necessarily an advocate. The trends you talk about may be streaking, transcendental meditation, or goldfish swallowing-all of which were new at one time. They may also be academically or scientifically oriented topics such as behavior modification, artificial intelligence, or the DNA molecule. You need not be an expert on these subjects. But when they come up, you should have a nodding acquaintance with them and be able to make some response.

4. Sports and recreation. Next to the weather, the subject most likely to be a common denominator of audience interest is sports. People who never listen to the news often will be very attentive to comments about their favorite baseball or football team. They may also want to know how the fishing is in certain areas or what the snow conditions are like during ski season.

5. Books, plays, and movies. You may not want to set yourself up as a critic-and that would be hard to do in a minute or less-but you can make brief comments about new books, movies, and plays. There is so much that is published and shown these days that people are grateful for some guidance as to what is worth reading or attending. Your opinion, even if not the final word, does give the public something to go on. In your spare time be sure you do more than watch television-everyone does that. Read as much as you can, and find out what is going on outside your own home.

Assuming that you have followed the above suggestions, had the experiences, and acquired the information-how do you work any of these things into your show? You may be able to tie it in to something you are doing on the air, to the music you have played or an announcement you have just read. Perhaps there is a relationship to the topic of a guest speaker you have had or will have on your program. Or you may just have to bring it up cold. Once the subject has been introduced, you can make periodic references to it between records. This will give some continuity to what you are doing. A word of caution, however: Do not assume that your listeners have been following your commentary right from the very beginning. Tailor your remarks so that anyone can pick them up from any point along the way and be able to make sense out of them. One of the reasons radio soap operas were so successful was that a listener could tune in any day and in a very short time be able to piece the story together. The writing was skillful enough to conceal the needed repetitiveness. Another feature of the "soaps" was that there were always several story lines running concurrently. You are not obliged to stay on the same subject throughout your program. You can develop several themes simultaneously.

The chief requirement for success in broadcasting is that you be an interesting person. Fortunately, while you are being interesting to other people you are being interesting to yourself as well.

SUMMARY

The most demanding task in radio broadcasting is knowing what to say when the microphone is turned on. The professional announcer or combo operator must be able to ad lib as well as read copy clearly and accurately. Style and timing are important attributes--as is correct pronunciation and enunciation. The voice that is transmitted must penetrate noise and other sounds that compete for the attention of the listener. The words must be clear and well modulated. Even more important, the professional announcer must have something to say that is either informative or entertaining. Almost anyone has the ability to close a micro phone switch and start talking. Being a professional broadcaster requires more than that.

TERMINOLOGY

Ad lib Project Enunciation Pronunciation Extemporize Set Initial sounds Telescoping Middle sounds Timing Pacing Vocal inflection

ACTIVITIES

Read the paragraph below into a tape recorder. Play it back to yourself and check your pronunciation and enunciation. Are all the syllables clearly sounded? Are you putting stress on the words that need to be highlighted? Are you able to make it sound natural and spontaneous? Are the proper names pronounced correctly? Good evening. Our concert this evening will begin with the Peer Gynt Suites numbers one and two by Edvard Grieg performed by the Boston Pops orchestra, Arthur Fiedler conducting. Then we will hear Mozart's Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, and finally selections from the opera Die Wallaire by Richard Wagner. May we remind you that tomorrow night our featured work will be the New World Symphony by Antonin Dvorak. Our opera selections will include excerpts from Verdi's Aida and Puccini's La Boheme. Here now is the first of the Peer Gynt Suites.

Play the tape for someone who is familiar with classical music and see if there are any mistakes in your pronunciation.

2. The following sentences were written to include words that have sound-a-likes.

Speak the sentences into your tape recorder; play back the tape and see if the words are clearly distinguished.

Accept the fact that everyone is right except you.

If you cannot adapt to changes, you must adopt a new philosophy.

The climatic conditions may be anticlimactic.

The diplomat attempted to comprise a compromise.

The dissolution of the marriage may lead to disillusion.

The exit does exist.

The sects performed rites of sex.

There is a statute against defacing a statue.